When the Rosetta Stone was discovered in 1799 in Egypt, by soldiers in Napoleon’s army, no one had been able to read hieroglyphs since late antiquity. Scholars had been trying to decipher the ancient Egyptian writing system, without success, for over a millennium. The text on the Rosetta Stone, a decree by priests outlining Ptolemy V’s achievements and generosity, was written in three scripts: hieroglyphs, ancient Greek, and Demotic, a later Egyptian writing system derived from hieroglyphs.

Using their knowledge of the Coptic language, the final phase of Egyptian, scholars first deciphered the Demotic script, setting the stage for the eventual understanding of hieroglyphs. The relationships between hieroglyphs, Demotic, and Coptic helped spur the crucial insight: that hieroglyphs were not used only ideographically, as symbols for concepts, but also phonetically.

Coptic itself had fallen out of daily use in the early modern period, supplanted by Egyptian Arabic, but it was and still is used as the liturgical language of Coptic Christians, the long persecuted Egyptian religious minority.

The Coptic language continues to facilitate scholarly insights. Ancient and early medieval Coptic texts remain valuable sources for religious studies, cultural studies, and history, as well as for the study of language and language change.

The National Endowment for the Humanities has supported a number of projects on and about Coptic language and culture, including the Coptic Scriptorium, a database of Coptic texts, which makes a wealth of material available to scholars and the general public.

Headed by Professors Caroline T. Schroeder of the University of Oklahoma and Amir Zeldes of Georgetown University, the Scriptorium provides access to a number of corpora from antiquity and the early medieval period. It includes transliterations, translations, search tools, and natural language processing, as well as a Coptic dictionary to help scholars glean as much as possible from these sources.

Texts are from the late fourth century and later, including the writings of Saint Shenoute the Archimandrite, a Coptic monastic leader whose sermons are informed by a deep knowledge of both the Bible and ancient Greek thought. The database also includes letters and everyday documents from Coptic monasteries. These can shed light on a variety of important questions, according to Schroeder. “What kinds of texts were being read and circulating in the Byzantine East? What was life like for Christians of premodern and early modern Iraq, Syria, and Egypt? How were church services being carried out?”

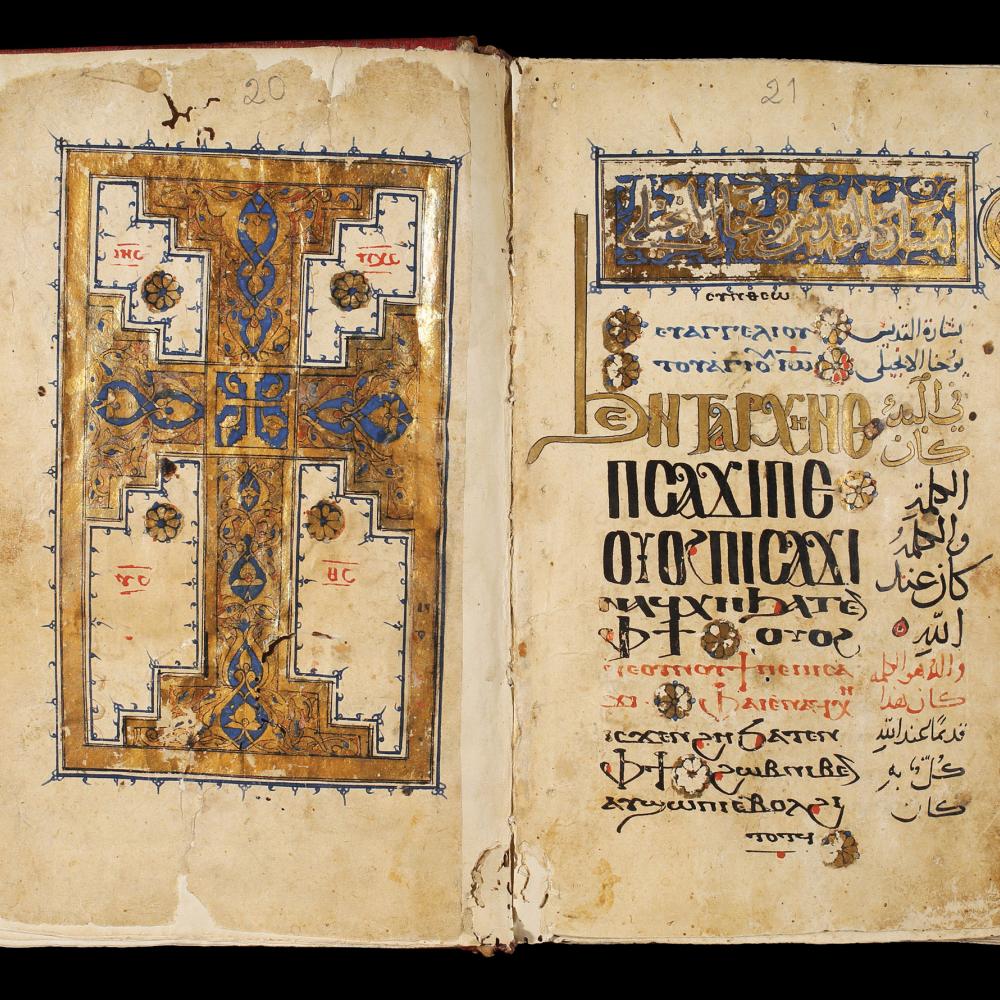

Schroeder, who has published a book on Shenoute, is herself currently at work on a project on girls and girlhood in the monasteries of the time. The NEH-supported Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, led by the 2019 Jefferson Lecturer Father Columba Stewart, has also worked to make ancient texts available, with a focus on preserving and cataloging texts in Coptic and other Middle Eastern languages. It now boasts the world’s largest digital collection of ancient texts.

Fr. Columba’s own work includes a monograph on John Cassian, a fourth-century monk who traveled among the ascetic monasteries of Egypt and brought Egyptian monasticism to the West, establishing monasteries in Gaul and influencing St. Benedict and the Benedictine order. Cassian’s journey in Egypt is a good example of the extraordinary period between antiquity and the Middle Ages, when numerous cultures, languages, and traditions overlapped in the Middle East. Many such stories remain to be told, and thanks to efforts like those of the Scriptorium and HMML, scholars now have the tools and the texts they need to tell them.