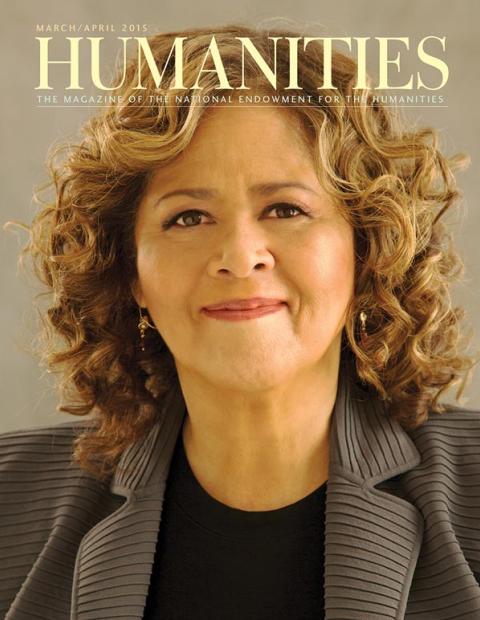

NEH Chairman William “Bro” Adams talked with the 2015 Jefferson Lecturer Anna Deavere Smith on February 3rd in New York City, discussing her method for developing stage material, her teaching, and her latest project.

WILLIAM ADAMS: Since you have so much experience with this kind of conversation, I want to start by asking, What makes a good interview?

ANNA DEAVERE SMITH: If I’m the interviewer. What makes a good interview? A good interviewee. That is an interviewee who would scream from the mountaintops what they have to say, and I just happen to be passing by. For my purposes, the interviewee needs to have a very, very strong will to communicate. So, it’s sort of the opposite of a person walking by the paparazzi, or if you think about a press conference with the president, you know, “Mr. President, Mr. President,” and he’s walking out the door, you know. I’m not interested in chasing the person who doesn’t want to talk. What I need is a person who has something to say, they want to get it off their heart, and I’m just so lucky to hear it.

ADAMS: When you’re being interviewed, do you have something you’re always trying to say?

SMITH: When I’m being interviewed, if I’m trying to say anything, I’m trying to say that people are very unique, and that nobody sounds like anybody else, and that if a person has a story, it’s worth stopping and listening. If it’s a media interview, I try to be really clear about talking points because you don’t have that long to say it. And God forbid you’re on one of those panels with people who talk louder than you and faster than you and seem to have more data.

ADAMS: I’ve been on those panels. You mentioned the story, and it reminds me to ask, How do you understand character? How do you understand that word, or how many different things does it mean to you?

SMITH: Well, when I left college, my best friend, Jane Robinson, who now works for a great organization in Washington called First Book—she wants to get a book in every kid’s hands—gave me a gift. She carved a quotation onto a plank board, a simple board—and she wasn’t an artist—she carved out, “Fame is a vapor. Riches take wings. Only one thing endures: character.”

I took that wherever I lived for nearly twenty-five years. The last place I hung it was my apartment in San Francisco in the nineties. I’d always hang it in a very prominent place wherever I wrote or studied. It gave me a lot of courage, particularly as a “struggling artist,” a young “struggling actor,” not having found my way. And, so, I thought about that quote as a mantra.

Character is what endures. It’s different than personality. One could say that it’s destiny. I think it is the journey. I think of it as the way water makes its way through the rock or mountain. You get your twists, you get your turns, and you have to ride that river.

ADAMS: Where do you get your stories, and where do you pick up your characters? What’s your process?

SMITH: I usually have a question that I’m trying to answer. The question I’m trying to answer right now is, How come the public schools are having such a hard time? And another question is, How come we have such a punitive society? A recent study showed that we incarcerate more people than any nation in the world. And when does that process towards incarceration begin? Some would say inside the schools. In the case of poor kids, data says they get suspended for sometimes minor infractions. We know a certain number of suspensions mean that they’re probably going to end up incarcerated. And data shows that poor kids of color are disproportionately disciplined, that it’s likely they will be out of school. But if you’re out of school, you’re in trouble, and then in the prison system, in juvenile facilities and then adult facilities. I am particularly focused on young poor people, mostly black, brown, Native American youths.

Back to process. I start talking to people about the project. I then go to a place that people tell me is going to be interesting—where something’s going on—and find one person who somebody says is interesting. And I start with that person, and they tell me about more people. In this project, I thought I was going to start in Oakland. Somebody said, “You need to go to Stockton.” A bankrupt city. And I sort of made my way around the town. Then a friend at the ACLU of Northern California let on that some injustices were being done to poor Native American youths, most of whom were part of the Yurok tribe. The reservation is up near Oregon. I went. They said there’s this incredible judge there. Met her. She basically assigned one of her staff to show me around.

You find the one person who really wants you to be there, and then they will invite you around in their world. I’m really dependent on that type of person.

ADAMS: How do you get from there to the kinds of things you take on stage?

SMITH: I record it, and then I learn what people have told me. When I was a girl, my grandfather said, “If you say a word often enough, it becomes you.” My grandfather was a businessman, in Baltimore, Maryland. Had a little shop on Pennsylvania Avenue—the street with black businesses—he imported coffees and teas. He only had an eighth-grade education. I now find out that’s pretty much what African-American men in 1915, 1918, had.

He said that to us, and it stuck with me. I put it together with some things that I found pretty extraordinary about speaking and learning how to speak Shakespeare in my first year in the conservatory. So, what they tell you when you’re learning to speak Shakespeare is to just speak the speech. Don’t think too much. And, of course, it’s in Shakespeare’s Hamlet that we find, you know, “Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced it to you, trippingly on the tongue.” You know, a director might say ’Please, just say the words, don’t add anything. Shakespeare knew what he was doing. He knew what he was writing.’ If you follow the language, lo and behold, you will find the feeling and the thought. There’s something mystical about the power of words to conjure realities. That’s what the theater is all about. When I first started teaching these ideas, one of my students who was becoming a priest said what I was talking about sounded a lot like prayer.

And so, in my case, I believe that people know what they want to say. My lofty goal has been to try to become America word for word. If, in fact, it is true that if you say a word often enough it becomes you, then I’ve been going around America for more than thirty years just talking to people and studying how they speak and trying to, you know, become them, inside of what’s often a social problem or even a catastrophe. And I try to represent multiple points of view.

ADAMS: You must be a pretty good listener.

SMITH: I came across something that I said about my paternal grandfather. Somebody tweeted it. What I said about him is that I was so lucky that “I had a grandfather who loved to talk, and I loved to listen.” I spent so many hours listening to him and to my maternal grandmother when I was a child, so that’s been with me for a long, long time.

Eudora Welty wrote somewhere—or perhaps it was on a recording that I heard this—that she was not allowed to sit at the dinner table on Sunday when all the relatives were there. She would sit out in the hallway and, as she said, my “ears would just open like morning glories.” I identify with that.

ADAMS: It’s a kind of respect, I think, listening to people.

SMITH: Or it’s fun. I think it is respectful to give people time to get out what they want to say, but it is also exciting. It’s musical. I love people’s expressions. I love originality in speech.

ADAMS: When you look at schools, what is it that you think kids are not learning?

SMITH: I don’t know because I don’t know enough about elementary and secondary education. I’ve been teaching in colleges and conservatory environments, and now graduate students at NYU. I taught at Stanford, I taught at USC, Carnegie Mellon. And, so, I’ve only been teaching a very sort of specialized person who wants to be expressive, who comes to me or gets into a college because they basically want to scorch some earth, and they believe we’re going to help them do it. They’ve got to say something. They’re on fire about it.

That’s really different from a kid who’s just trying to make it through, who might be bored to tears, who hasn’t been given the opportunity to get switched on to something that they really want to know. As I said, my new project is about the “school-to-prison pipeline.” I am calling it “Notes from the Field: Doing Time in Education,” and my goal is to find out what happened that caused us to go from what I was able to take advantage of in the sixties, with what Johnson did, to the situation of today. Here we are, sixty years after Brown v. Board of Ed, and some people say we’re more segregated than we were then. How did that happen?

Johnson is the one who called education the “fifth freedom,” adding to what FDR said were the “four essential human freedoms.” And for Johnson, the fifth freedom was the freedom from ignorance. The kids that I’m interested in are the ones who aren’t getting a chance. Many of them come from environments of violence and trauma, and I am asking, What do we need to do to intervene, to give them a chance?

I think schools have to be something else than what they are right now, and we shouldn’t keep blaming teachers, because the problem is much bigger than what they’re doing in the classroom.

ADAMS: What switched you on as a student, and when did you get switched on?

SMITH: I think I was switched on before I went to kindergarten. My mother was a teacher. All her friends were teachers. And, like I said, I loved to listen. That probably started really young. Wanting to know, that probably started really young. And I really loved school. I guess what switched me on was something that I don’t remember about my youth.

And then, in high school, what switched me on were my friends. I had gone to an all-black elementary school. The junior high was mixed, but nobody got along at all. In high school, something happened where, you know, there was a bunch of us—black, white, Jewish, Christian— who were very interested in each other. And I just have to credit my friends even more than my teachers about what happened to me then. It was a very important time in my education. An all-girls school, public.

ADAMS: How did acting, and theater, become such a big part of your life?

SMITH: That didn’t happen until I was much older, after I had gotten out of college. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. I had $80, an overnight bag. Got in a car with my friends in a Howard Johnson’s parking lot is the story, with my mother crying as I left with these crazy-looking friends from college. And we all went across the country, looking for something.

The one who gave me the plaque that said “Fame is a vapor,” she wanted to save the earth. I was looking for the revolution, and when I got there, it was over. 1972. It was done. So, I ended up in an acting class, at a very good conservatory in San Francisco, the American Conservatory Theater, which was also an excellent theater with a repertory company of fifty-two actors. That is unheard of now.

I remember sitting in the acting class—it was a complete fluke that I’d be there at all—and, I thought, well, you are interested in social change, here all these people in front of you are changing. And, I mean, I’m talking about they’re in an Arthur Miller play or a Neil Simon comedy. And, I thought, Maybe I should just learn about this kind of change first before I take on the big thing of national social change.

Then there were a series of lucky events that led me to believe that acting, storytelling in the theater, and also teaching others to do so were all things I could do. It was something I developed a passion for, and I spent every waking hour for three years trying to learn everything I possibly could about it. I sort of moved very quickly through. Ended up getting an MFA, getting a place in a repertory acting company, teaching, and getting in a union, and stuff like that.

ADAMS: But was it just serendipity that you showed up in an acting class?

SMITH: True. My first job when I got to California was working in a drive-in movie theater.

ADAMS: Where was that?

SMITH: Belmont, California, and I was the assistant manager, which mainly meant taking care of the popcorn. Nobody really came to that theater to watch the movies, and so they didn’t really come in to buy much.

When you’re starting out, your goals are very limited. I had to ride a bike to the movie theater, I didn’t know how to drive, so the first thing was to make enough money to learn how to drive. Then the next thing was to buy a car. And then I got a great job at a community college, San Mateo Community College. By the way, I really hope that the president’s initiatives about community colleges come through because that was an incredible job, and we changed a lot of people’s lives. After that, I had, you know, an apartment, and I had a car, and I had a job, and a great boss, and I was bored. I thought, well, what will I do?

I took a dance class. One of my colleagues who came to watch me said, “Annie, you ain’t got no rhythm.” So, okay, that’s the end of that. Then I thought maybe basketball would be interesting, but I’m not really like that. And I called up the theater, the American Conservatory Theater, and I said, Do you need any stage managers?

This is how green I was, and I still remember the woman. Her name was Beulah Steen, the only black person really around in that place. She was on an old-fashioned switchboard. And she said, Oh, my dear, they’re union. I said, Well, do you have any acting classes? And she told me about an acting class that was starting up and I stumbled down there and got admitted with a very dramatic, loud rendition of Lady Macbeth.

The guy who changed my life at that point was just sort of a very calm guy, very elegant. He was the only person who wore a tie in that Bohemian theater, and he shined his shoes. We all remarked on the fact that he shined his shoes, because it was so odd, everyone else was in Birkenstocks or tennis shoes. He just kind of sat still for a while, and then he said, “So, you want to be an actor.” I just said, “I don’t know, maybe, I guess so.”

ADAMS: So, then you started to study theater more formally.

SMITH: Yes. I had three years of real conservatory training. Every hour of my day for three years was then spent reading plays, writing plays, reading about playwrights, theater and teachers of acting throughout the twentieth century.

ADAMS: Who were the writers that really got to you?

SMITH: This is really an interesting question because it shows you how much American culture has changed and how much the canon has changed. So, it was Williams. It was Miller. O’Neill, Inge, Shakespeare, Molière, some Albee, perhaps a Jacobean drama. No women authors. No authors of color. I was lucky enough, in my third year, to have a chance to work with students of color, which required me to find some plays that at least explicitly called for people to be other than Caucasian. It’s really pretty extraordinary that we have opened up the canon so much, though I know people would like to see more. When I started, my students thought that Sam Shepard was so progressive that I thought maybe I should be bringing his plays into the studio in a brown paper wrapper. Few years later he gets the Pulitzer Prize, becomes a movie star. The students tended to be as conservative as the teachers. They’d ask, What is this weird stuff? So, the canon has changed in every way, dramatically not just with regard to race, gender, and sexuality. The official American voice has changed.

ADAMS: Do you gravitate toward any particular writers who are writing now?

SMITH: I’m very interested in television writers because I’ve been acting on television lately. Some people say that, at least in our business, that television is where some of the best writing is. Television may have even stolen people away from the theater. A writer like Aaron Sorkin, who’s one of my favorite writers, he did start in the theater. He’d be an amazing writer in the theater. But, in a way, maybe this is the theater now. He reaches a broad audience. He tells stories that people want to hear. Shonda Rhimes is another one.

ADAMS: You’re from Baltimore originally. Do you go back to Baltimore?

SMITH: Not often. I’m going to go for this school-to-prison pipeline project. I feel that this project is taking me home.

San Francisco is also my home. I went there when I was twenty-one, and I made my adult life on my own there, and I go back there as much as I can.

I love cities. I like looking at people. San Francisco is pretty much my favorite city.

ADAMS: Will this be a chance to get reacquainted with Baltimore?

SMITH: Yes. Now let me tell you what I’ve been trying to do. I mentioned that when I was in acting school, the canon was pretty determined. And I spent most Sundays over at City Lights Bookstore, which is one of the last standing independent bookstores in the United States of America.

ADAMS: Yeah, I love City Lights.

SMITH: And I would go down to the basement of City Lights and rummage around in there just to find something different. When I got out of school, there was this real kind of, I would say urgent, move to say, Look, you over here, you’re a woman, come here. You’re black, come here. You’re Asian-American, come here. You’re Chicano, come here. So if you have something to say, write about yourself.

There was an extraordinary opportunity for people from different cultural and different gendered backgrounds, different relationships to sexuality, different histories, different assumptions, to come forward and write, paint, dance, from their own experiences. And I thought—you have to excuse my arrogance, I was in my twenties—I thought, well, that’s a kind of a spiritual dead end.

ADAMS: Yeah, well, the twenties.

SMITH: I was in my twenties, right? That’s a kind of “spiritual dead end.” “I’m not going to write about me. I’m going to write about the other.” I, Thou. So, my idea was, I’m not going to write about 3701 Springdale Avenue in Baltimore, Maryland. I’m going to go across America trying to find the people who are not like me at all. And, of course, then try to embody all of that. It seemed to me that my specific freedom papers, originally authored—to my mind—by Martin Luther King Jr., were about coming out of boxes of separation, boxes of segregation. I thought affiliation politics were another form of separation.

I went pretty far, and I think one of my favorite interviews was with a bull rider that I met and portrayed from Shoshone, Idaho. And I think I’ve met many people who are nothing like me at all: the young man who was accused of beating up Reginald Denny, the white truck driver in Los Angeles during the L.A. riots, all kinds of people, Hasidic Jews in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, police officers in Los Angeles after the Los Angeles riots, one of the jurors in the Rodney King trial.

But now, given that I’ve made many plays by looking for that which is not me, I feel like it’s time to go home. And “going home” to me means not just going home to Baltimore, which will be one site of my research for this project, but it also means going home to those values that those teachers had who were a part of launching me in the world, my mother being a very important one of them, and my aunts, and all the people who were there.

ADAMS: You made an interesting comment that I just thought of when you talked about looking at other people, not at yourself. In Letters to a Young Artist, you said something about the Boomer generation having gotten stuck in some way. And you recommended that we get unstuck. Is this what you meant, that we should pay attention to people not like ourselves?

SMITH: Well, maybe, and what I want to say now is not my idea. This idea comes from a friend I’ve now made on the journey of my new education project. She is the Chief Judge of the Yurok Tribal Court in Northern California. Her name is Abby Abinanti. She said she thinks that after the sixties, we made real strides, and that we made adjustments in government, so government was a part of the change for the better. But then, we liberals went our merry way. And now we turn back and see that whole communities have been left behind. We ask, What happened to the house we thought we built? We weren’t watching, thought it was all okay, and now we have to go back. I don’t think it’s malicious. I think we just thought, Oh, we’re free of those problems now.

ADAMS: Yeah. We’ve learned lately we’re not free of some.

SMITH: Right.

ADAMS: When I look back on those times, and when I talk to students about it, I’ve found that there’s this kind of horror about the sixties. That always surprises me a little bit when I see it in younger people’s eyes. When you look back, do you have any regrets about that time, or things you would’ve wanted to have done differently?

SMITH: Whew, that’s really a wonderful question. But I think, first of all, when we romanticize that time, we forget about the amount of bloodshed. People were killed in Vietnam. There were, notably, three big murders. We lost, as Gloria Steinem once put it to me, and only she could turn a phrase like this: “There were three murders, two Kennedys and a Martin Luther King.”

I went to a school that was all-women, at the time called Beaver College, now called Arcadia. And I was one of seven Negro girls. The school had never had that many nonwhites before we arrived. The seven of us were very different from each other. We were cautious about approaching one another. And then King was killed in the spring of our freshman year, and we automatically unified, called ourselves the “Beaver College Blacks.” We managed in that time to get the first black professor hired and, you know, a curriculum. Many other people in our school did other things that made a difference.

But maybe if I had chosen a school where I was swimming in a bigger pond, maybe I would’ve done more. So I don’t know if it’s regrets, and this is very odd for me to say. I tend to be pretty hypercritical. I would say, given my circumstances, I did the best that I could. In some ways I wasn’t really prepared for the sea change. I came from a pretty protected environment in Baltimore. I wasn’t really prepared to completely absorb what was going on in the world.

I still came out of those times with a passion for social justice, and that has certainly been fertile soil for most of my work.

ADAMS: Well, I was about to say that you have sustained a remarkable degree of commitment. And you’ve gotten a lot of people to listen to you. Which is especially impressive, given the strength of criticism that you face.

SMITH: I think it starts with the interviews. One of the first things we learned in acting school was “Don’t judge the character.” If you judge the character, you will kill the character. So when I’m sitting across from somebody, if I start judging them, I begin to worry that they’re not going to talk to me. There’s no point in continuing the interview if I start judging. I may as well say “Thank you very much for your time” and leave.

I remember a person saying to me after Fires in the Mirror, a play about racial tension in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, between blacks and Jews. And, you know, I take both sides, so I can’t win. Extreme people on either side are very disappointed that you would even let the other person have a voice. I remember a good friend of mine said, Well, just how far will you go? And, when you think, “Well . . . far.” When you think of the characters in dramatic literature, you know, well . . . far.

ADAMS: I think one of the things you do so well and that great literature and theater do so well is to, without judgment, open people up, open situations up, and reveal depth.

SMITH: Well, we have so many people to do the judging. We have real judges. We have politicians. We now have the media, which takes extreme sides.

I’ll tell you something that happens with my graduate students at NYU. For part of the term, they work on narratives about their lives, usually, sort of seminal moments. And it wouldn’t surprise you that, as they are for the most part in their twenties, sometimes these have to do with their parents.

ADAMS: I’m shocked.

SMITH: And, this year, mothers looked pretty bad in these performance pieces. The students write and then perform these. And, so, my theme this year was “Give your mother a chance.” At first the response was, Huh? She ruined me. She was crazy. She couldn’t deal with my sexuality. She didn’t like my appearance. Et cetera. But once they understood that “give your mother a chance” really meant strengthening the drama—putting the audience in the position to decide for themselves—then they were behind it. They saw how exciting it was, how much the stories unfolded and opened, how much variety the stories had, how much more color. “We don’t indict our characters in here,” is what I told them. Everyone’s struggle has dignity, was another mantra.

Really putting your feet in somebody else’s shoes. You know, some people would talk about empathy. When you asked me what’s missing in the schools, I would have to say that across the board, at every level from elementary school through graduate school that empathy is often in short supply. Empathic behavior and investing in, building the empathic imagination should not be rare. And maybe I should now make my campaign for arts in the schools. You take art out of it, you take out empathy. You take sports out, you take out empathy. Team members have it for each other if not for the other side. You take out extracurricular activities where kids are likely to be with others who are not in their own chosen cliques and groups, you reduce empathy. You make it all about math and science, you reduce empathy. You diminish the humanities, you reduce empathy and human understanding.

ADAMS: Yeah, it is a problem. One other city in near proximity to Baltimore is Washington. Have you spent a lot of time in Washington?

SMITH: Yes, I spent, in the nineties, real substantial time there doing many interviews about the relationship of the press to the president. I wrote a play about it called House Arrest, and I wrote a book called Talk to Me. That was a fascinating time. I spent almost five years in Washington, and people there made me think of something the late Roger Kennedy, a wonderful scholar, said of Thomas Jefferson: that he could never be found in verbal undress. I think of the language of Washington as a sort of haute couture of language. It’s courtly language. You kind of have to read between the lines. No one’s going to let it all hang out when I turn the tape recorder on. I have a lot of respect for the people in Washington actually, and for how hard they work.

ADAMS: What I’m discovering is that there’s this other Washington, the Washington of daily life. It’s a complicated city, and it’s really changing. It seems to me a deeply segregated city.

SMITH: Many of our cities are, including our favorite city, San Francisco. You could pretty much go around certain areas of San Francisco and never see an African-American person.

ADAMS: You mentioned President Johnson, who signed the legislation that brought NEH into existence. I wonder what it means to you to be giving this talk on the fiftieth anniversary of NEH.

SMITH: You know, I think one of the stresses on the humanities right now has to be the cost of education because why would you go to school and study poetry?

ADAMS: Well, it amplifies all that career anxiety.

SMITH: Yeah, it has to be about career. It can’t be about what we do, although you and I both know very successful professionals who started in their undergraduate careers as humanities majors, and then went into other, sometimes lucrative, professions.

ADAMS: Yeah. I think we’re successful because we did that stuff. I really do.

SMITH: I’m sure glad that NEH and NEA are here to step up to this moment and do what they can to make sure that these things that I consider the soul of America stay alive: our histories, our stories, our imagination. And when you ask about these two institutions, NEH and NEA, it makes me think I should go back and look at some of the history of it. It’s probably a very exciting time to think about. Maybe it’s trite to ask how they could be more relevant, but it could be worthwhile to revisit the need and to make it clear in another way.

ADAMS: So, you have had a very accomplished career. Do you have a vision of what’s next? Is it a continuation of this good work you’ve been doing?

SMITH: Well, I’m not a person who is sent, you know, fifty scripts, so I’m still in a position to be responsive to opportunity. In terms of my own theater work, I’ve always created my own opportunities, so that’s what I’m doing with the school-to-prison pipeline project. And what’s next in this project is planning how we can use the theater as a place to convene people, and then have them be the second act.

We are thinking about new ways to actually engage audiences, and this is something that I have been thinking about a lot since the nineties. I founded and directed an institute at Harvard in the summer called the Institute on the Arts and Civic Dialogue, which is all about the relationship of art and social change.

But you quickly realize that, as artists, we can only do part of it, and hope that what we’ve done will inspire other people who have other resources and other talents to do more. So, the question is, How do you do that? Do you just say goodnight and shut the door, or can the theater be a different type of civic organization? And I’m very pleased to say that many of my colleagues who run theaters believe it can be another type of civic organization. We’re a secular country. We’re divided along religious lines. The church can’t be a truly ecumenical convening place. You know, maybe the baseball stadium could be, or a concert hall. But the theater really is the place where we speak. We speak and we transmit ideas. It’s a place that could be a new kind of town hall, a new type of civic center.

ADAMS: Give me an example of a kind of civic engagement that might flow from this.

SMITH: When I was talking about American Conservatory Theater, I mentioned there were fifty-two actors. Well, those days are gone. Those acting companies don’t exist at that level of scale anymore. As actors, we have to be nomadic in search of opportunity. Most of our jobs are short term. So actors can no longer be the center or the heart of a theater as they once were. So who’s the heart? The administration? Well. Maybe. But the administration, I believe, is ultimately wired to serve the artist. It’s just that we are now structured in such a way that artists come and go. Not with dance companies or orchestras, but with theaters we come and go.

So, I’m talking about creating a real community of people—audience members—who wouldn’t have known each other before they came, but who have a feel and a commitment to be there, not just like subscribers or donors, but they’re treated like subscribers and donors and board members, right? So, I think it’s about creating this group, this community who becomes a real core of the organization. What if a core audience becomes the heart of a theater and so becomes the heartbeat of a community?

ADAMS: That’s a great idea. I hope it works. So, you’re going to give this big lecture. What are you thinking about saying?

SMITH: Well, I like to start, wherever I speak, by talking about my grandfather: “If you say a word often enough, it becomes you.” And I like to invoke Walt Whitman, who wanted to be absorbed by America and have it absorb him. I like to invoke Shakespeare, about how I learned through Shakespeare the power of what happens when you just say the words, how it actually evokes the character.

If you take almost any conversation, and if we had something comparable to a microscope, if we just took a little sliver of it and put it on a slide, put it under the microscope, you would see that every walking person has absorbed not just their narrative, their biography, but the world around them. You have evidence of when they lived and how they lived.

So, I would like to talk about that and talk about some of the wonderful Americans I’ve met, and probably perform a couple of them. And, you know, take out little pieces of what they’ve said, and sort of inspect them the way we might look at other kinds of texts.

ADAMS: Those are all good humanities things. Well, thanks for doing this interview and for being our next Jefferson Lecturer.

SMITH: Thank you.