In 1924, the fate of Black Swan Records was sealed. The remarkable early success of the small Harlem company faded, as its dealers canceled orders and returned shipments unopened. Bigger companies had begun to usurp its markets. Then the advent of radio threatened the whole phonograph industry. Finally, the young firm’s founder and president, Harry Pace, was forced to surrender. As he wrote in an emotional appeal to his board of directors, “Does it mean anything to you to know . . . that when we began business there were 24 record making concerns and today there are only seven? . . . How could we survive with a meager capital of about $40,000 and a limited market when concerns with millions . . . either died or were mortally wounded?”

Publicly, Pace announced that the company making Paramount Records would begin leasing and selling the Black Swan catalog. Always the businessman, he characterized the arrangement as a merger, a kind of commercial breakthrough, and a forward-looking thrust into the future. An advertisement he ran covering the entire back page of the Chicago Defender, the nation’s most widely read African-American newspaper, hailed the deal as “the biggest news in phonograph record history.” Inside the paper, an article called readers’ attention to the back-page announcement, referring to Paramount’s “all-star,” “inspiring” roster, and promised to keep readers abreast of future developments. Pace tried hard to keep up a good face.

The reality was more grim, as many people understood. Condemning the deal, Chandler Owen, a prominent political activist, likened it to a “merger” between the lion and the lamb, with the lamb winding up in the lion’s belly. Owen voiced the underlying truth: The Paramount deal marked the effective end of Black Swan, not the propitious beginning of a new era. Today, it might seem surprising that in the 1920s a prominent political activist took an interest in the affairs of a small record company—or that numerous other public figures did as well—but Black Swan was no ordinary record label. The eminent W. E. B. Du Bois himself stood as a champion of Black Swan, the first major black-owned record company, and served on its board of directors. By 1924, Black Swan was known not only as a pioneering black-owned business but also as a radical experiment in black politics and culture.

Activist and music publisher Harry Pace launched Black Swan in 1921, believing that making records represented an important form of social and economic power. With Black Swan, he strove to start a new kind of record company, which combined the powers of music and business in the cause of racial uplift and the fight for social justice. He conceived Black Swan with two interrelated goals. Musically, the company would issue records by African Americans in all genres—not just the popular styles most commonly associated with African Americans, such as blues, ragtime, and comic songs, but “serious” music as well, including opera, spirituals, and classical music. The effect of such a catalog would be to challenge stereotypes about African Americans, promote African Americans’ cultural development, and refute racist arguments about African- American barbarism. At the same time, the company would be a model of small-business development, inspiring and instructing African Americans in capital accumulation and the potential for economic self-determination.

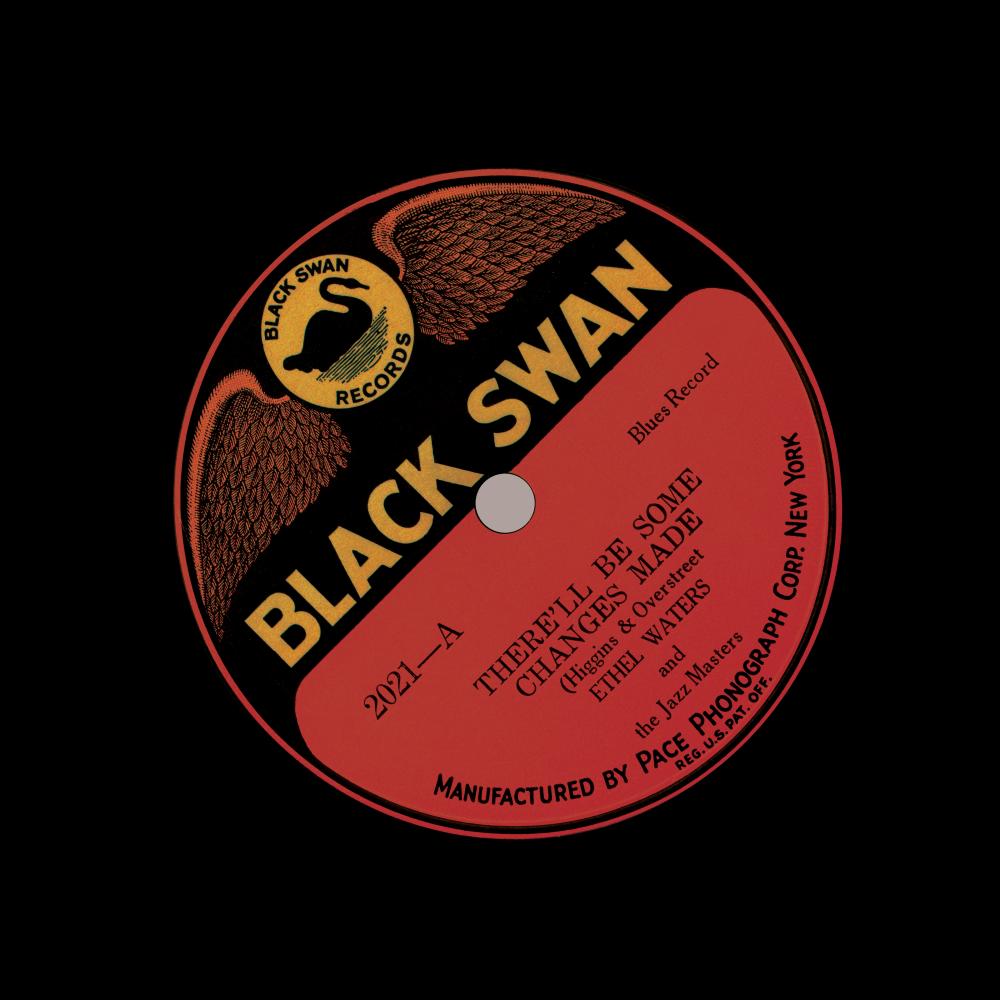

Despite the rapid rise and fall of this unique company, many of its goals were achieved, at least for a time. Black Swan issued more than 180 recordings in a wide range of styles, sold hundreds of thousands of discs, and distributed them around the United States and abroad, finding favor among and beyond African-American consumers. Black Swan launched the recording careers of Fletcher Henderson, Ethel Waters, Trixie Smith, and Alberta Hunter, and put out records by a host of talented musicians unlikely to have found other recording opportunities. Meanwhile, the company emerged as a prominent and influential black-owned business, and, as a manufacturer, distinguished itself even from other black-owned companies by having rare control of its manufacturing capital.

This is not, then, a typical Harlem Renaissance story, and even suggests how misleading the term Harlem Renaissance often is. In the 1920s, a surge in activity among writers, visual artists, and musicians took place not only in Harlem but in African-American communities around the country, and it represented wholly new circumstances and opportunities, not a “rebirth” in any meaningful way. Many African Americans were radicalized by World War I and began the postwar period, in the words of the Chicago Defender, with a host of “new thoughts, new ideas, new aspirations.” This surge of newness energized not only the arts—as the term Harlem Renaissance often connotes—but all forms of social, political, and economic activism, often simultaneously. Black Swan represented the effect of just this kind of ferment, bringing together a range of activist impulses. Enmeshed in both the politics of culture and the culture of politics, Black Swan grew out of the particular conditions and opportunities of New York but sought to serve the interests of “the race” everywhere. The conceit of Black Swan was that a record company could be a powerful agent in the fight for social and economic justice.

At the end of World War I, the music industry was already well on its way to becoming big business in the United States, producing goods worth more than $335 million and exerting a far-reaching influence on the sound and character of American popular culture. The music industry, however, was not an equal opportunity employer. Phonograph companies issued thousands of titles in dozens of foreign languages to cultivate consumers in “ethnic” and immigrant communities, while they all but refused to issue records by African-American performers and disregarded African-American consumers. There were some exceptions, but even these tended to fall only within restrictive racial stereotypes (such as the “humorous” recordings of George Washington Johnson or Bert Williams, or the religious singing of the Fisk Jubilee Singers). They had little effect on balancing power in the industry. The prevailing pattern saw African Americans excluded, or at best marginalized, in this increasingly influential medium of American popular culture, despite letter-writing campaigns and other forms of pressure by African Americans.

Several developments broke this impasse. A number of lawsuits and court decisions, and the expiration of some crucial patents, loosened the grip of the three phonograph giants (Victor, Columbia, and Edison). This made it possible for new, independent record companies to enter the market on solid legal footing for the first time. Then, one of the new labels, OKeh Records, issued two records by an African-American vaudeville singer, Mamie Smith. These historic recordings from 1920 were the result of a dogged campaign by the African-American songwriter and publisher Perry Bradford, who recalled that he “walked out two pairs of shoes” and endured “many insults and [much] wise-cracking” from record men before securing an agreement with OKeh’s Fred Hager. For his part, Hager allegedly received threats of a boycott of OKeh products if he had “any truck with colored girls in the recording field.” But Bradford convinced him to take a chance on Mamie Smith. When the two records appeared, in February and August 1920, they sold phenomenally well among African Americans and heralded the possibility of a new era of African-American music.

It was in this environment that Harry Pace, a young, bright, charismatic businessman, launched Black Swan to produce a broad range of music by and for African Americans. The only precedent for such a venture was the small, mail-order company Broome Records, established in Medford, Massachusetts, in 1919, and dedicated to black concert music. Pace was likely familiar with Broome, but what he sought for Black Swan was even more ambitious: the creation of a record company that would serve as a vehicle for cultural and economic uplift. Black Swan’s musical goals, emphasizing diversity and quality, would inspire and empower African Americans, on the one hand, and challenge (white) public opinion about African Americans’ attributes and capabilities, on the other. In the fractious African-American politics of the early 1920s, Pace’s goal was to build a prominent black-owned business that cut across ideological lines, bringing together competing political positions around their shared support for black economic self-determination. Closely, though unofficially, aligned with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Black Swan benefited from the direct support and guidance of Du Bois, who invested the project with heavyweight political credibility. Indeed, here was a record company committed to much more than just selling records.

Pace was born the son of a blacksmith in rural Covington, Georgia, in 1884. He met Du Bois after enrolling at Atlanta University, where Du Bois was on faculty, and subsequently became his protégé. Graduating valedictorian in 1903, Pace worked as the business manager of Du Bois’s new journal of African-American ideas and culture, the Moon Illustrated Weekly, based in Memphis. The underfunded venture lasted only eight months, but it initiated Pace into the business of cultural politics. (It also inspired the formation a few years later of the Crisis, the influential NAACP organ that served as Du Bois’s main outlet from 1910 to 1934.) For the next several years, the talented and energetic Pace pursued ventures in education, politics, and the bedrock industries of African-American business: banking and insurance. He taught Latin and Greek for two years in Missouri, after which he returned to Memphis, secured a position at the black-owned Solvent Savings Bank, and became increasingly active in local politics. He returned to Atlanta, working for six years as secretary-treasurer of what was probably the most prominent and respected black-owned business of the era, the multimillion-dollar Standard Life Insurance Company, and established Atlanta’s first chapter of the NAACP.

These activities represented only one side of Pace’s pursuits. At the same time that he was working at the Solvent Savings Bank in Memphis and then at Standard Life in Atlanta, he was involved in a music-publishing partnership with Beale Street’s favorite son, W. C. Handy, the self-proclaimed “father of the blues,” who pioneered arrangements and publications of blues music. Pace had penned some “first-rate song lyrics,” Handy remembered, and together they composed and published several successful songs. They established their own publishing firm, the groundbreaking Pace & Handy Publishing Company, of which Pace served as president. In 1918, Pace convinced Handy to move their growing business to New York, where, despite continued commercial success, they also confronted repeated indignities from “the beast of racial prejudice,” as the normally equable Handy put it. In New York, Pace recalled, “I ran up against a color line that was very severe.” When he tried to convince phonograph companies to record African Americans performing material besides blues and popular music, he was told, “It would ruin their business to have a colored person making records of high-class music.”

After years of trying unsuccessfully to get recording dates for African-American performers, Pace saw a door open with the release of Mamie Smith’s first record, whose songs he and Handy published. Soon Pace left his partner to start a record company that combined his commitment to black-owned business and his belief in the social importance of music. All of Pace’s professional experiences to this point—his relationship with Du Bois, the personal contacts he developed in Atlanta, Memphis, and New York, his business experience in banking and insurance, and his music business experience with Handy—converged on his new venture.

The name Black Swan would have echoed, in many contemporaries’ ears, that of the Black Star shipping line, Marcus Garvey’s widely discussed venture just starting. In fact, the name alluded to Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield (ca. 1824–1876), the most accomplished African-American concert singer of the nineteenth century, who was often known as the “Black Swan.” To those who caught the reference (which Du Bois pointed out in an editorial in the Crisis), the name signaled the company’s cultural ambitions. Throughout the nineteenth century, many people came to think about music—that is, “serious” music—as a powerful force that could both unite and ennoble people. For African Americans, this notion of musical uplift had a dual character. Oriented toward African Americans, it suggested that music could elevate and enrich a people abased by slavery and its aftermath. But music could also break down social barriers, demonstrating to society at large African Americans’ common humanity. Music was a means of both aiding African Americans in their spiritual striving and improving relations with others.

Pace assembled a talented board of directors (including the prominent and well-connected Du Bois) and built a musical foundation for the company with several outstanding employees recruited from his and Handy’s publishing company. Most notably, Pace enlisted Fletcher Henderson, soon to be one of the foremost bandleaders of the 1920s and thirties, as the phonograph company’s recording manager, and William Grant Still, later an eminent composer, as Black Swan’s in-house arranger. The first Black Swan record appeared in May 1921, a sentimental, inspirational song “At Dawning”—the symbolism of its title could hardly have been a coincidence—backed with “Thank God for a Garden,” sung by the concert vocalist and pianist Revella Hughes. In the following months Black Swan issued African-American spirituals, arias by Giuseppe Verdi and Charles Gounod, Christmas carols, the first recording of a work by the composer R. Nathaniel Dett, and the first recorded performance of “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” the so-called Negro national anthem. The point of such recordings, noted one newspaper article, was not to depreciate “the commercial value of comic songs, ‘blues’ and ragtime songs,” but to supplement those styles with “every type of race music, including sacred and spiritual songs, the popular music of the day, and the high-class ballads and operatic selections.”

Accompanying the “serious” recordings, was a wide range of popular music, including ragtime, blues, jazz, and dance songs. These accounted for two-thirds of the total number of titles Black Swan issued and all of its best-selling records. Within this domain, the most crucial performer was a young Ethel Waters, whose record “Down Home Blues” backed with “Oh, Daddy” became so enormously popular that it reversed the fledgling company’s economic fortunes. In her autobiography, Waters recalled when she first entered the company in 1921, she had a lengthy discussion with Pace and Henderson about “whether I should sing popular or ‘cultural’ numbers.” Underlying this exchange between Waters and Henderson and Pace were uncomfortable class tensions. Waters wrote, “Remember those class distinctions in Harlem, which had its Park Avenue crowd, a middle class, and its Tenth Avenue. That was me, then, low-down Tenth Avenue.” Waters did not fit the recognized social profile for a singer of “cultural” songs, regardless of the fact that she, like Revella Hughes and most other musicians, had a repertoire encompassing a variety of styles. In the end, the two men decided she would sing popular blues material and agreed to pay Waters the sizable sum of one hundred dollars for two songs. (She was then performing for thirty-five dollars a week plus tips.)

Thanks to Waters, by the end of 1921 Black Swan had turned a small profit of $3,100 on revenues of over $104,000. By the spring of 1922, after twelve months in business, the company may have sold as many as four hundred thousand records. Along the way, it propelled the careers of not only Waters but also Alberta Hunter and Trixie Smith and became a leading force in the cultural and commercial development of the blues.

For Black Swan’s complex goals, blues records were problematic because they exposed a tension between the priorities of business and those of musical uplift. On the one hand, the blues records were essential to Black Swan’s commercial success—that is, to its goal of economic uplift. On the other hand, the aesthetic (and thus spiritual and moral) value of the blues remained questionable, and the company tolerated and supported such music only up to a certain point. A paragon of middle-class decorum, music director Fletcher Henderson ensured that the music never got too hot, and despite the company’s professed catholicism, it distanced itself from the rough-hewn aesthetics of the black working class. In a fateful and telling decision, Black Swan turned away Bessie Smith, whose coarse, boisterous style departed sharply from the lighter, more lyrical singing of most of Black Swan’s popular vocalists. Such a position had serious economic consequences, too, for Smith went on to record for Columbia and became the biggest-selling blues vocalist of the 1920s. But for Black Swan, blues was acceptable only to the point that it did not threaten middle-class respectability. But, of course, this was exactly what made Bessie Smith’s music so exciting.

Pace also promoted his high ideals through an audacious advertising program that sought to connect consumer behavior with the social mores and economics of making music. He called readers’ attention time and again to Black Swan’s unusual, goal-oriented identity. To underscore the difference between Black Swan and other record companies, many of its advertisements in black newspapers emphasized the company’s tongue-in-cheek slogan, “The only genuine colored record. Others are only passing for colored.” Black Swan advertised regularly in the radical black press, frequently featuring a polemical statement about the company’s social mission and goading readers to support the venture as a matter of political solidarity with “the race.” More than simply trying to sell records, these advertisements urged readers to understand the connection between cultural achievement and market relations. They positioned Black Swan not as an alternative force to consumer culture, at odds with the rest of society, but rather as a transformative force within it. By buying these classical records, argued one of the advertisements, “you will Encourage Us to make more and more of this kind,” by shaping what dealers would stock.

Black Swan issued its last records in the summer of 1923. Its demise was precipitated by a perfect storm of ill-timed capital expansion; sharply elevated competition in the blues and jazz fields (whose commercial popularity Black Swan had helped beget); and the advent of radio, which destabilized even the largest, most secure phonograph companies. Beneath these circumstantial factors there stood the problem of the irreconcilability of Black Swan’s different goals, which from the start had pulled the company in opposite directions. Although Black Swan achieved some early success, it rested on a delicate balance of priorities that was impossible to maintain.

Attempts to right the company exposed the fundamental illogic of approaching music through racial categories. Under intense economic pressures, Black Swan took a step completely antithetical to its stated musical mission—namely, it reissued records by white artists whose identities were hidden behind generic pseudonyms in Black Swan’s ostensibly all-black catalog. The white stage-singer Aileen Stanley became “Mamie Jones,” while Lindsay McPhail’s Jazz Band appeared as “Fred Smith’s Society Orchestra.” Amazingly, different groups might be given the same pseudonym, as with Black Swan’s releases of the “Laurel Dance Orchestra,” which was really either the Tivoli Dance Orchestra or the Wallace Downey Dance Orchestra, depending on the recording. This surreptitious practice began as early as November 1921 and increased considerably after the purchase of a record-pressing factory, which provided a ready supply of free material from the bankrupted Olympic record company.

Although small record companies at the time often issued discs—sometimes under pseudonyms, sometimes not—recorded by other companies, those companies did not, of course, repeatedly insist that they employed “colored singers and musicians exclusively.” Ironically, though, Black Swan’s commercial deception demonstrated the contingent, extrinsic character of racial categories in music—which had been one of Black Swan’s basic goals. What is most striking about Black Swan’s commercial sleight of hand is that people apparently did not detect anything amiss; there were no indignant editorials, no boycotts, no letters of protest. The silence suggests that people either did not care or could not perceive any difference. Racial difference was not audible; rather, it was artificially and arbitrarily assigned. In this way, Black Swan’s high-minded program of musical uplift and its desperate, deceptive reissuing of recordings by white musicians were less at odds than they appeared, for both laid bare the speciousness of racial boundaries in music. By rejecting musical categories based on race, Black Swan showed that racial distinctions were neither natural nor fixed. Likewise, the fact that records by black and white performers could be interchanged without anyone noticing proved how unstable music categories based on race actually were.

In the study of epistemology, the black swan is a metaphor for the problem of inductive knowledge, that is, the derivation of general conclusions about the world from specific examples or experiences. The problem is, could one really conclude that all swans were white simply because one had never seen a black one? (Indeed, such swans were later discovered in Australia.) Black Swan Records posed a similar challenge to knowledge based on appearances, by offering counter instances of African-American manufacturing, commercial development, and musical diversity. Pace understood that record companies made culture in the broadest sense. Their recordings, their advertisements, the performances of their artists—all these contributed to the prevailing ideas and social relations in society at large. The meaning of music, he understood, depended not just on what was recorded but also which messages were associated with those recordings, how those messages were communicated to consumers, and how the recordings functioned in the market. Black Swan’s burden was to chart a course between elite culture and popular culture, between the color blindness of music and the racism of the music business, between ideologically based enterprise and the impinging realities of capitalist markets. The hazards of such a course were evident; the way to navigate safe passage was not.