Reflecting on the arduous path that brought him from poverty in rural Alabama to being one of the most successful and sought-after portrait painters in the country, the artist Simmie Knox once said, “Things that I thought were liabilities turned out to be assets.” But it took an awful long time for those liabilities to turn Knox into the first African-American painter of an official presidential portrait.

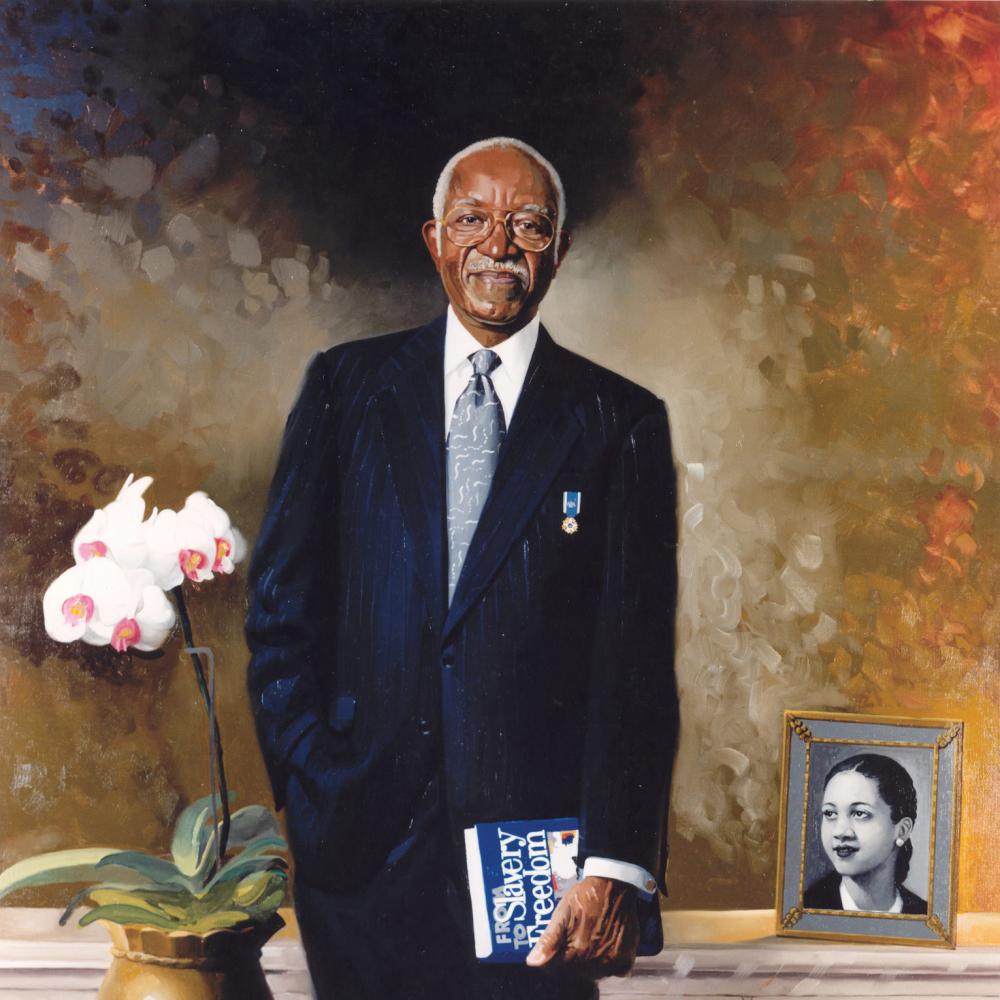

A new documentary film supported by the Delaware Humanities Forum, Strokes of Justice: The Simmie Knox Story, written and directed by Sherry Dorsey, chronicles Knox’s struggles and his late-in-life success as the painter of President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, Supreme Court Justices Thurgood Marshall and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the eminent historian John Hope Franklin, New York City Mayor David Dinkins, Alex Haley, Lou Rawls, Bill Cosby and his family (a dozen canvasses in eight years), and a host of other luminaries.

Knox was born in the Alabama town of Aliceville, about halfway between Tuscaloosa and the Mississippi line, in 1935. His parents divorced when he was three, and he lived with relatives in another small town and then in Mobile. Playing baseball one day he was hit in the eye and so badly injured that he needed a year to fully recover his sight. To strengthen his damaged eye, the nuns at his Catholic school assigned him drawing exercises, which not only repaired his vision but revealed a talent for art. The nuns arranged to have a local amateur artist, the neighborhood mailman, tutor Knox on Saturday mornings. After high school, Knox joined the army, then enrolled at Delaware State College to study biology, paying his way with a job in a textile mill; but as he told a newspaper interviewer in 2004, “I knew, deep within me, that I wanted to be an artist.”

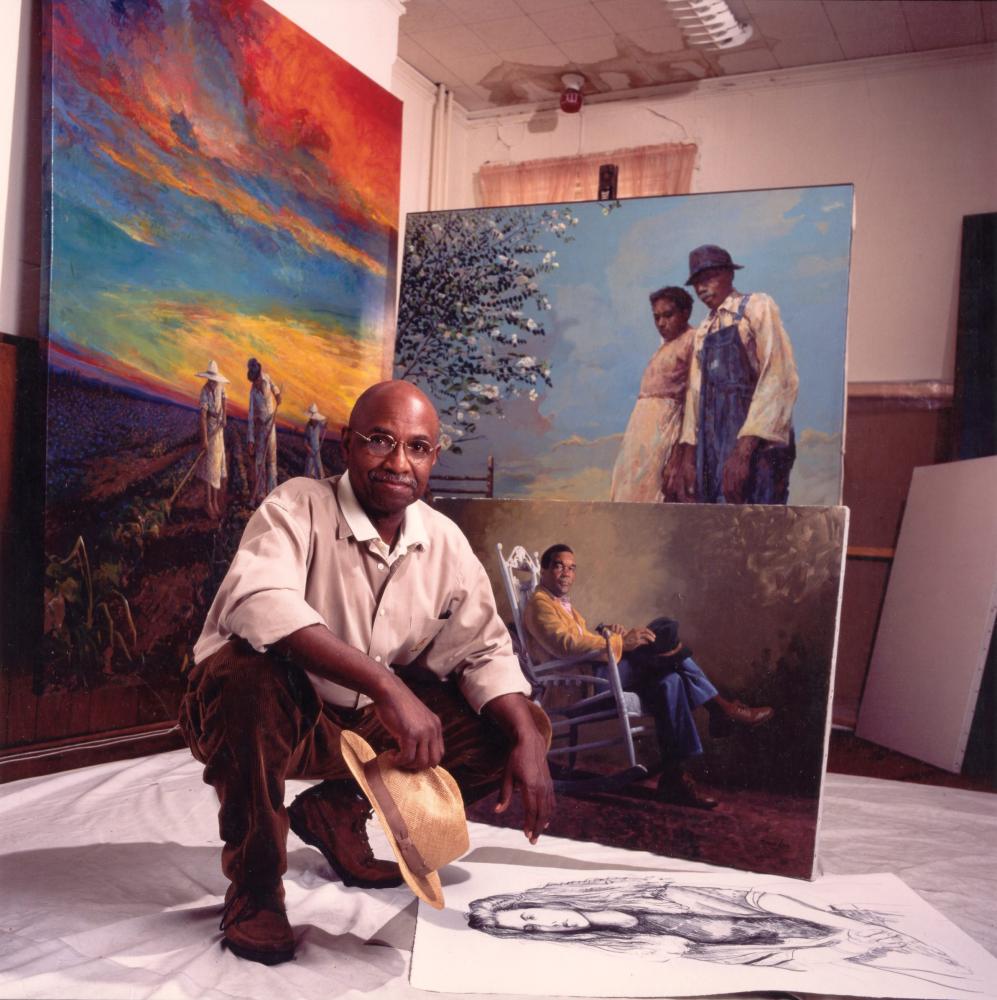

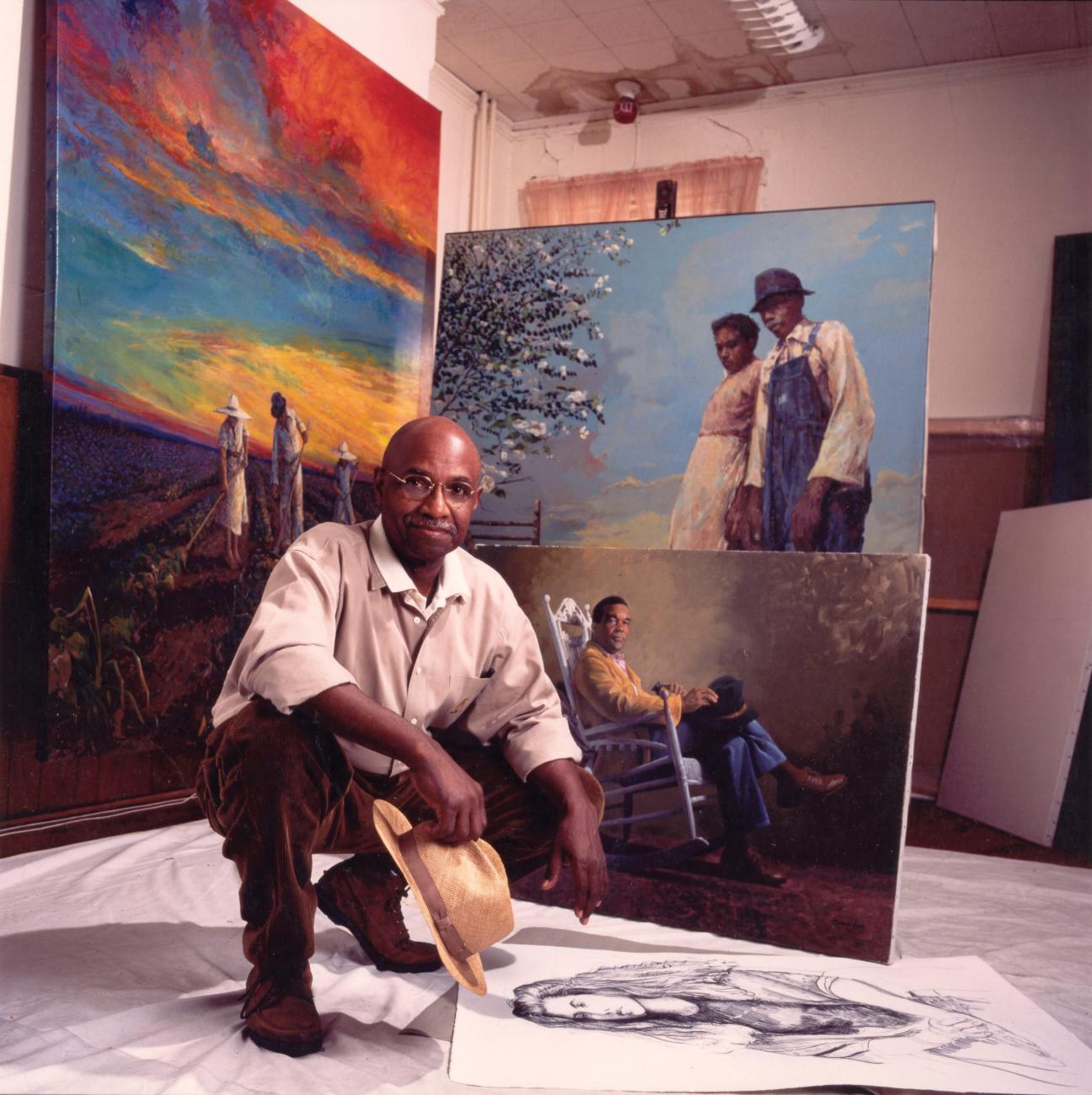

After studying at the Tyler School of Arts at Temple University, he took up his career, not with portraits but with abstract works, while teaching art at a number of different schools for nearly two decades. An anecdote in the film captures a moment in Knox’s career that would be comical except that it shows the struggle of a young artist trying to find a foothold in the marketplace only to have the caprices of the wind carry off his dreams. Unable to pay for professional shipping of his work, Knox used to transport his abstract paintings from his studio in Wilmington to Washington, D.C., on his station wagon. They were huge canvases—the film shows an old photograph of Knox standing beside a canvas that dwarfs him. More than once he would tie the canvases to the roof of the car, only to have the wind make them take sail on I-95. Flying off in his rearview mirror, they formed for just a moment a truly abstract kaleidoscope of tumbling colors and shapes before falling to the pavement into the inexorable flow of traffic. “There go my paintings,” Knox recalled thinking.

When he lost a teaching post in 1980, Knox decided to abandon abstraction for portraiture. As he recalled in a newspaper interview, “With abstract painting I didn’t feel the challenge. The face is the most complicated thing there is. The challenge is finding that thing that makes it different from another face.”

One of Knox’s sitters in Delaware was Justice Randy J. Holland of the Delaware Supreme Court. But as the film depicts in one of its arresting moments, Knox had already painted Holland many years earlier, when the judge was just a child. Knox was working in a factory in Milford, and during lunch he would sit outside and sketch. One of his coworkers in the factory was struck by Knox’s dedication to his craft and by the beauty of the small creations he turned out every day, so he asked Knox if he could paint a portrait of his son from a photograph. Knox obliged with a lovely small pastel of a handsome boy, staring wistfully out at the world, that became a family treasure. The child in the pastel grew up to be the distinguished jurist, who commissioned Knox to create his official portrait—a more sober and serious work, to be sure, but one which the judge’s wife says captures the character of her husband so much that she likes to look at it when he’s away.

After years of struggle and frustration, Knox got a break when the curator David Driskell introduced him to Bill and Camille Cosby, who were seeking an African-American portraitist. The Cosbys hired him, and helped to find other clients. Connections help, but the talent has to be there. In the film, Justice Ginsburg describes how she first encountered Knox’s work. During her tenure on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, Ginsburg attended a series of unveilings of official portraits, many of which seemed to bear little resemblance to their supposed subjects. But at the unveiling of Judge W. Spottswood Robinson III’s official portrait, Ginsburg thought—“This man has captured Judge Robinson just as he is. . . . It was remarkable.” She asked Judge Robinson’s secretary for the name of the artist who had done the painting, and was handed Simmie Knox’s business card. After Knox painted Justice Ginsburg, she brought him to the attention of President Clinton’s staff when they were looking for someone to do his official portrait. The competition for the commission was stiff, and Knox sat for several interviews before he was finally selected. In the end, the president and the painter found a bond in their common southern roots.

In telling the filmmakers about his technique, Knox remarks, “The eyes are important because when you’re painting a portrait of a person you want to have some kind of interaction. . . . We engage through the eyes.” An anecdote in the film reveals the deep roots of that desire to connect. After his parents divorced when he was three, Knox lost all contact with his mother. He didn’t know if she was living across town or half way across the country. A sense of loss haunted him into his adolescence, and he recounts how he walked the streets of Mobile, staring into the faces of passersby, hoping to spot his mother. “For some strange reason I thought, ‘One day, I'm going to find my mother. I'm going to see her face.’ . . . That played a role in my looking at faces.” That was how this acclaimed painter of faces learned to look for the hidden human element, the features that seize memory and emotion, that proclaim beyond question—this is the person.