The death of champion boxer Muhammad Ali is an occasion to remember one of the strangest moments in popular culture, when Ali collaborated with legendary poet Marianne Moore on a work of verse.

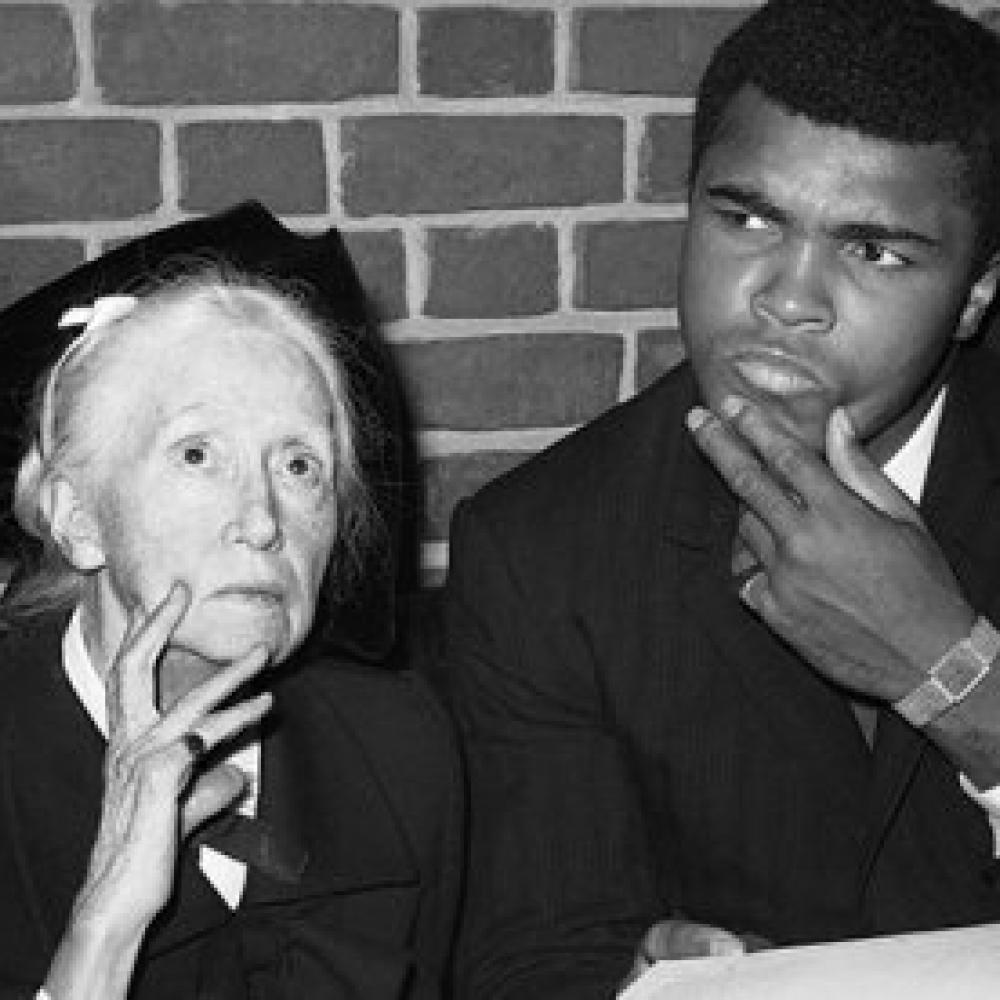

They met in the winter of 1967, shortly before Ali’s heavily anticipated match with Ernie Terrell, and made an unlikely pair. He was a streetwise athlete who liked to turn a phrase, especially against his opponents, and she was the elderly queen mother of American letters, a primly erudite figure with a penchant for lace collars and tricorn hats.

But it was precisely because they were so different that writer and editor George Plimpton decided to bring Ali and Moore together. Plimpton created a lively cottage industry by exploring the boundary between literature and sports, arranging to perform brief stints in professional football, baseball, and hockey games, then writing wryly about his experiences in such well-received chronicles as Paper Lion and Open Net. His first-person accounts, coined “participatory journalism,” played on the contrast between Plimpton’s patrician sensibility and the rough-and-tumble world of the locker room.

Plimpton apparently hoped for an equally comic clash of cultures when he enlisted Moore in a project. He would take her to various sporting events, observing her reactions and documenting the result. As the plan went, she would also write her own take on the outings, the collaboration forming a book. “Alas, the project was never completed,” Plimpton later lamented. But, in the meantime, the pair embarked on a couple of excursions—to a World Series game and a boxing match—that provided fodder for two Plimpton essays.

Moore’s meeting with Ali at a Manhattan restaurant was supposed to be part of the shtick, and as Plimpton implies between the lines of his account of the get-together, much of the afternoon unfolded as a publicity gimmick. The flamboyant Ali arrived with no apparent idea of who Moore was. But, ever the self-promoter, he warmed to the headline possibilities after learning of Moore’s stature as a poet, suggesting that they cook something up for the Associated Press.

Here’s how Plimpton describes what happened next: “He announced that if she was the greatest poetess in the country, the two of them should produce something together—‘I am a poet, too,’ he said—a sonnet, it was to be, with each of them doing alternate lines. Miss Moore nodded vaguely. Ali was very much the more decisive of the pair, picking not only the form but also the topic: ‘Mrs. Moore and I are going to write a sonnet about my upcoming fight in Houston with Ernie Terrell,’ he proclaimed to the table. ‘Mrs. Moore and I will show the world with this great poem who is who and what is what and who is going to win.’”

Ali was, indeed, a poet of sorts, using clever memorable rhymes to taunt his rivals in the ring. “Henry, this is no jive. The fight will end in five,” he said of his 1963 match with boxer Henry Cooper. “I have wrestled with a alligator. I done tussled with a whale. I done handcuffed lightning, throwed thunder in jail,” he would later boast of his prospective 1974 match with George Foreman.

While Ali’s approach to poetry sounded intuitive, Moore was, as the professional wordsmith, more formal and deliberative, crafting jeweled observations on clocks and steeplejacks, a china swan and a paper nautilus. When, at Ali’s urging, the pair worked together on a poem, the result—scribbled on the back of a restaurant menu—proved as unusual as their partnership. Moore’s chief contribution was the title. “We will call it ‘A Poem on the Annihilation of Ernie Terrell,’” she told Ali.

Moore wasn’t up to the kind of spontaneous composition Ali favored, so the boxer essentially completed the verse himself. Here’s a sample:

After we defeat Ernie Terrell

He will get nothing, nothing but hell,

Terrell was big and ugly and tall

But when he fights me he is sure to fall.

If he criticized this poem by me and Miss Moore

To prove he is not the champ she will stop him in four . . .

It’s pure doggerel, little more than a footnote in the country’s cultural history. But the poem points to what Ali and Moore shared, in spite of their obvious differences. Like Ali, Moore shrewdly cultivated her public persona—a reality at the heart of a recent Humanities profile of the celebrated poet. Although Plimpton and Ali appeared to be using Moore for an elaborate gag, the ostensibly dear, daft little lady was no doubt using them to advance her own profile.

Moore died in 1972 at age 84; Plimpton died in 2003 at 76. With Ali’s passing, the three principals in a peculiar meeting of a poet, a literary journalist, and a boxer are all gone now.

It was a meeting that Moore eagerly embraced. When asked by Plimpton if she’d like to connect with Ali, she didn’t hesitate. “I do not see any reason,” she told Plimpton, “why I should not meet someone who assures everyone ‘I am the greatest’ and who is a poet nonetheless.”