Rambling through the Frick Collection on East Seventieth Street in New York City, it’s easy to be awed by what steel magnate Henry Clay Frick amassed during his lifetime. Towering, larger-than-life Van Dyck portraits envelop an entire room of this mansion; winsome Vermeers draw you close to share a secret; room after room, everywhere you turn, another masterpiece takes your breath away.

Imagine what it was like to live among these works every day, as Frick and his family did—it certainly made an impression on his only surviving and adored daughter, Helen Clay Frick. She became intimately involved in choosing and cataloging her father’s collection, and then set her sights on an art historical project so monumental that it rivaled her father’s accomplishments.

Helen envisioned a records library documenting every western work of art in Europe and the United States. And she came close. What became the Frick Art Reference Library is her brainchild. It holds over 350,000 books, periodicals, and annotated auction and exhibition catalogs related to art. With 1.2 million images in its Photoarchive (nearly half unpublished), representing more than forty thousand artists from the fourth to the twentieth century, along with extensive provenance records of ownership, sales, and condition, the Frick Library has been the go-to archive for art historians for more than seventy-five years. For many works of art that have been lost or destroyed, it holds the only records of their existence.

The library officially opened in 1924, when Helen was in her mid-thirties, but in many ways she had been preparing for it most of her life. At the age of eight, she was already influencing her father’s collecting. According to the biography Helen Clay Frick by Martha Frick Symington Sanger (Helen’s grandniece), Frick was considering buying a painting by Charles-François Daubigny, and for fun he told Helen that he planned to exchange four other pictures for it. But Helen had her own opinion on the matter, as Frick told the story. “She promptly said the Detaille could go, as she did not care much for it, but the Chevalier and the Rico could not be parted with, and although she liked the Dupré, yet she might be willing that it should go.” Earlier, when Frick chose not to purchase a certain painting, he justified his decision with the statement, “It does not please me, nor do Mrs. Frick and my daughter seem to think it worthy of the artist.” By the time she was seventeen, Helen had traveled to Europe nine times, accompanying her father on his art tours of the Continent and keeping detailed records of the trips. “Each trip provided a foraging, shaping, and deepening of her interest in art, architecture, and history,” writes Sanger. Helen frequented the Louvre, the Uffizi, the Prado, the Pinakothek, Britain’s National Gallery, cathedrals and churches, as well as exclusive visits to private collections such as the Rothchilds’, or the studio of Señor Aureliano de Beruete, where Helen recorded that her father purchased two paintings by El Greco.

She was not a typical American tourist, shepherded around to peer at old masters. She visited sites repeatedly, forming and reforming her opinions on works well known and obscure. Of Fra Angelico’s frescoes in the cells of Florence’s San Marco, Helen said they were “gems in color . . . in expression, & in detail. They really should be examined with a microscope!” Helen was particularly fascinated by archives. She relished the manuscripts at London’s Record Office Museum and the Musée des Archives in Paris. “It contains hundreds of letters from celebrated people, but none interested me as much as the following: Last letter written by Marie Antoinette . . . last letter written to her father by Charlotte Corday, letters of Napoleon, Robespierre, of the many celebrated [F]rench writers. . . . those of many kings, queens, & others of the royal families.”

By twenty-five, Helen was passionately cataloging the family’s collection, filing away photographs and provenance data, as well as researching other works by the same artists. Following her father’s death, Helen took a trip in in 1920 to Europe to do more research on many of his purchases. She also wanted to inspect the damage World War I had inflicted on the art and architecture she had known as a girl and as a Red Cross volunteer during the war. She compiled before-and-after pictures of cathedrals, villages, and other monuments that had been destroyed. She met with staff at the Louvre and at the Chateau de Chantilly. The chateau staff had been able to move artwork to safety before the Germans occupied the estate and stabled their horses in the art gallery.

While in London, she met Sir Robert Witt, secretary of the National Gallery of Art, who gave her a tour of his pioneering Library of Reproductions, in which 150,000 photographs and postcards of great art, representing over eight thousand European artists from the thirteenth to the nineteenth century, were organized alphabetically within shelves and shelves of boxes for the use of scholars in the relatively new discipline of art history.

Helen was blown away. “May I copy-cat your library?” she asked. Witt answered that she could, and that he would help. As soon as Helen returned home to New York, she began the task of accumulating the thirteen thousand records that her adviser, Paul J. Sachs, said would be the minimum needed for a working collection. She began with her family’s own assortment of catalogs, photographs, and postcards, and moved on to hiring agents in England, France, and the Netherlands to purchase catalogs and photographs in Europe. She employed professional photographers to take pictures of artwork “in the days when one could almost buy some works of art for the cost of making photographs of them,” according to Everett Fahy, director of the Frick Collection in the seventies and early eighties.

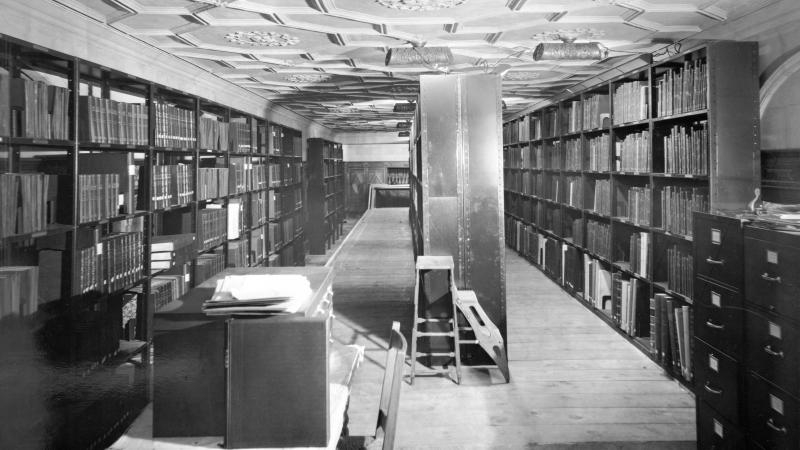

Every reproduction was carefully mounted and labeled as to artist, title, collection, etc. On the back went a trove of information for future scholars: dates, known engravings, exhibition history, collection history, bibliography, records of reproductions, condition. If other reproductions were available, they were noted. All were filed alphabetically by artist, and cross-referenced by subject, region, mythology, other attributions, and themes and objects in the artwork. The boxes began to fill up their temporary home, the elegant bowling alley in the subbasement of the Frick mansion, a luxurious room common in the homes of men of Frick’s stature at the time. (Don’t ask me how bowling went from a sport of the uber rich to that of middle-class suburbanites with polyester shirts and rented shoes—that’s a different story.)

Within two years, the library was already being consulted by prominent art historians—Bernard Berenson made an early visit and became an adviser—and making headlines. The New York Herald prophesied that “the Reference Library should be a great help not only to students of art and architecture but to all who are interested academically or commercially in professions or business with which art is linked. The historian, the novelist, the playwright, the decorator, the theatrical producer, the costumer, the furniture maker—all will have at their command, when the work is given to the public, the most complete collection of its kind ever assembled. The historian of water supply will find Da Vinci’s plan of a boring mill for pump logs. The Wild West novelist will be able to see how Remington dressed his characters.”

Helen Frick was determined to make it the most complete collection possible, which meant obtaining records of art that had never been recorded. From photography campaigns between 1922 and 1967, the Frick Library acquired 57,000 large-format negatives. In Italy, photographers rigged up their car batteries to light church interiors that had always been too dim to photograph. Mario Sansoni worked under contract for years, traveling to remote locations and collections in Italy in order to make glass photograph negatives for the library—8,129 are attributed to Sansoni, including those of frescoes by Baronzio da Rimini in Ravenna that were destroyed in World War II.

In fact, many more artworks would have been lost in World War II if not for the Frick Library. With memories of the destruction from World War I, Helen realized that her archive was vulnerable; even New York was not out of the reach of German U-boats. So in spring 1941, the Frick closed its doors in order to microfilm every mounted photograph in the collection. The staff finished four days before the attack on Pearl Harbor and stored the microfilm in an underground bank vault near the city. The day after, it headed off by train to an even safer, more remote location in the Midwest.

As the war commenced, the Allies took an interest in preserving Europe’s cultural heritage even as its planes were bombing and its troops were invading. There was no other institution in the United States that could equal the vast amount of information on European art needed to direct an invasion safely around the continent’s irreplaceable treasures. In 1943, the doors to the Frick Library once again closed to the public and opened to the Committee on the Protection of Cultural Treasures in War Areas. For almost two years, the committee worked with the Frick staff and resources, compiling lists and detailed maps for use in the field of all the known art and historic buildings that the Allies might encounter. After the war, the Frick’s resources were put to use returning art that had been looted, a task that continues today.

Documenting art in the United States at that time meant road trips to faraway places when roads and cars were unreliable. Between 1922 and 1967, the Frick Library staff went on more than a hundred photography expeditions to various sites around the country, knocking on doors and visiting estates to fill out the library’s records of early American art. Often a media advisory would arrive first to a locale’s prominent newspaper, encouraging individuals to make their collections available for the archives of the Frick. Sometimes, the destinations were too remote to have gotten the memo. Katherine McCook Knox retells in The Story of the Frick Art Reference Library: The Early Years about a fortuitous visit to Front Royal, Virginia:

Mrs. Lee, Miss Frick and Mr. Park arrived rather late one afternoon due to rain and heavy going over mountains. They were registering at the hotel when Mr. Park asked the clerk if Mrs. John Marshall lived anywhere nearby. “Right across the street, you can see the house from here,” was the reply. Wasting not a minute, and regardless of the hour, the trio left the hotel, crossed to the other side of the pavement, mounted the porch steps and knocked on the door, which was immediately opened by a tall lady in starched calico. “Does Mrs. John Marshall live here?” “I am Mrs. Marshall.” Mr. Park then proceeded with a statement whose preamble was gradually becoming a formula: “We are on an errand for an art reference library which is interested in obtaining photographs of early American paintings for the use of students. We are not trying to buy any pictures but we are looking for a Gilbert Stuart painting of Robert Morris’ two daughters, and we have reason to believe that it is somewhere in this neighborhood. Can you give us any information as to its actual whereabouts?” The lady’s answer was electrifying. “You just come right on in. How did you know where it was? I only got it last night.”

A recent fire had destroyed the home of a descendent of one of the sisters in the painting, Hetty Morris, married to James Markham Marshall, the younger brother of the chief justice. Its biography is complicated, according to the library’s records: “It has been said that because of adverse criticism of this painting, Stuart intentionally slashed it with his palette knife. Lawrence Park thinks the canvas was deliberately and carefully cut to divide it into two, distinct portraits. It is apparently a trial painting for another picture which was not executed. According to Robert Morris, after the picture was cut, the pieces were found by his daughter, Jane Stuart, in a garret. She put the pieces together . . . and the picture went to James Markham Marshall, the husband of one of the subjects.” Thence, it was rescued and wound up propped against a table at Mrs. Marshall’s house.

In the past, scholars would have had to schedule an appointment and traipse to the Frick Library itself (as beautiful as it is) to study a reproduction of this painting; but soon, these colonial sisters and their neglected chess game will join fifteen thousand images from the Frick’s American art excursions already searchable and downloadable online. With two NEH grants, the library will have thirty thousand of these images digitized and accessible to everyone with an Internet connection by 2013, showing high-resolution images that can be carefully inspected with a virtual magnifying glass, and also linked to their entire data reference material. In a manner of speaking, all e-roads will lead to the Frick—art historians searching either through Google, or ArtSTOR, or Arcade (the online catalog of the New York Art Resources Consortium), or FRESCO (Frick Research Catalog Online) will be able to seamlessly download images and data from the Frick Photoarchive.

There was an urgency to this project when it began in 2009; six thousand acetate negatives were rotting away in storage. “It was like a plague, spreading to surrounding negatives. The whole room smelled of vinegar,” says Inge Reist, chief of Research Collections and Programs and head of the Photoarchive Department at the Frick. The deteriorating negatives were quickly put in freezers to stop any further damage, and prioritized for digitizing.

Entering the digitization lab, far from the beaten path in the maze of the Frick Library, is like entering a submarine. Everything is painted gray—the walls, the ceiling, the columns—there are no windows, and it has a deliberate stillness that is similar to being underwater. All the better to scan with: The gray helps the eye stabilize shade and color variations and the lack of movement cuts down on dust. Two dedicated technicians stagger their schedules so that the cutting-edge scanning equipment is never idle during the workday. Every scan is done in triplicate, and a raw file of the negative is kept for future reference. Sizing, color correction, and other refinements make it ready for the website.

What is most remarkable is the easy interface for anyone searching the archive—either as a scholar, a genealogist, or just someone with a general interest. With a keyword search, visitors can find out quickly what has been digitized, and what is available for further research at the Frick. Type in “Metcalf” and nine images pop up, ranging from a painting by John Singer Sargent in the collection of one Robert T. P. Metcalf in Beverly, Massachusetts, to a charming portrait by Eliab Metcalf of his three-year-old son, John Trumbull Metcalf. By linking to the full library record on this portrait, you can see that it is still in possession of Mrs. Walter Sands Martin, widow of the sitter’s great-grandson. Call up the name Peale, and 258 images documenting the work of this famous American artistic family appear, including Sarah Miriam Peale, whose work was previously unknown to this researcher. That this is all available—visual records incorporated with MARC data—is extraordinary. MARC is the machine-readable cataloging language used by libraries to share information online, and for many years it resisted compatibility with visual content. “Shoehorning visual information into MARC has always been an issue. This is groundbreaking,” says Reist.

And the biography of a work of art never ends. Experts may go back and forth over centuries, attributing a piece to different artists or to different owners. Those conversations continue and are solicited, recorded, and updated at the Frick. With easier accessibility to records, new information is flooding in. Recently, a couple from Pennsylvania conducting genealogical research contacted the library after they discovered the FRESCO records and Frick Digital Image Archive images for portraits of two of the wife’s ancestors, Mr. and Mrs. Peter Eisenbrey, painted by Jacob Eichholtz. The portraits were photographed by Thurman Rotan in 1959 in an exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the couple have updated the current ownership of the paintings to a relative in Philadelphia.

“As using electronic resources becomes more and more part of the day-to-day reality of research, we are delighted to know that the Frick Art Reference Library's Photoarchive not only remains relevant, but can actually serve a broader audience with more varied research challenges than ever before,” says Reist. “Helen Clay Frick’s original vision to make available enormous quantities of images of works of art, seems to come into full flower in the digital age. I have no doubt that she would have embraced the digital future with vigor and determination.”

This article was last updated on February 14, 2013.