In 1899, American artist Henry Ward Ranger searched the New England countryside for a place to establish a new American school of painting—a place reminiscent of the vibrant art communities he admired while studying abroad—a retreat where fellow artists could escape the city and paint en plein air. He came upon Old Lyme, a sleepy town situated between Boston and New York. “I want to drive you around & see a little of this beautiful country, where pictures are made—your station is Lyme,” Ranger wrote to his New York agent.

“In the late nineteenth century, there is this whole generation of artists who came back to the United States after studying in Europe's art centers—places like Paris, Munich, and Laren—and were looking for picturesque country locations to capture the essence of the American people and the American landscape, and the American past,” says Jeffrey Andersen, director of the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme. “And at that time, the American past was in New England.”

That first summer in Old Lyme, Ranger rented a room in a slightly rundown late Georgian mansion-turned-boardinghouse owned by Florence Griswold, the unmarried daughter of a once prominent shipping captain. He soon proposed the idea of an artist colony to “Miss Florence,” who had been taking in boarders to ease the financial burden of maintaining her family home. Florence agreed, and in the summer of 1900, Ranger returned with a group of artists, which included the painters Lewis Cohen, Henry Rankin Poore, Louis Paul Dessar, and William Henry Howe.

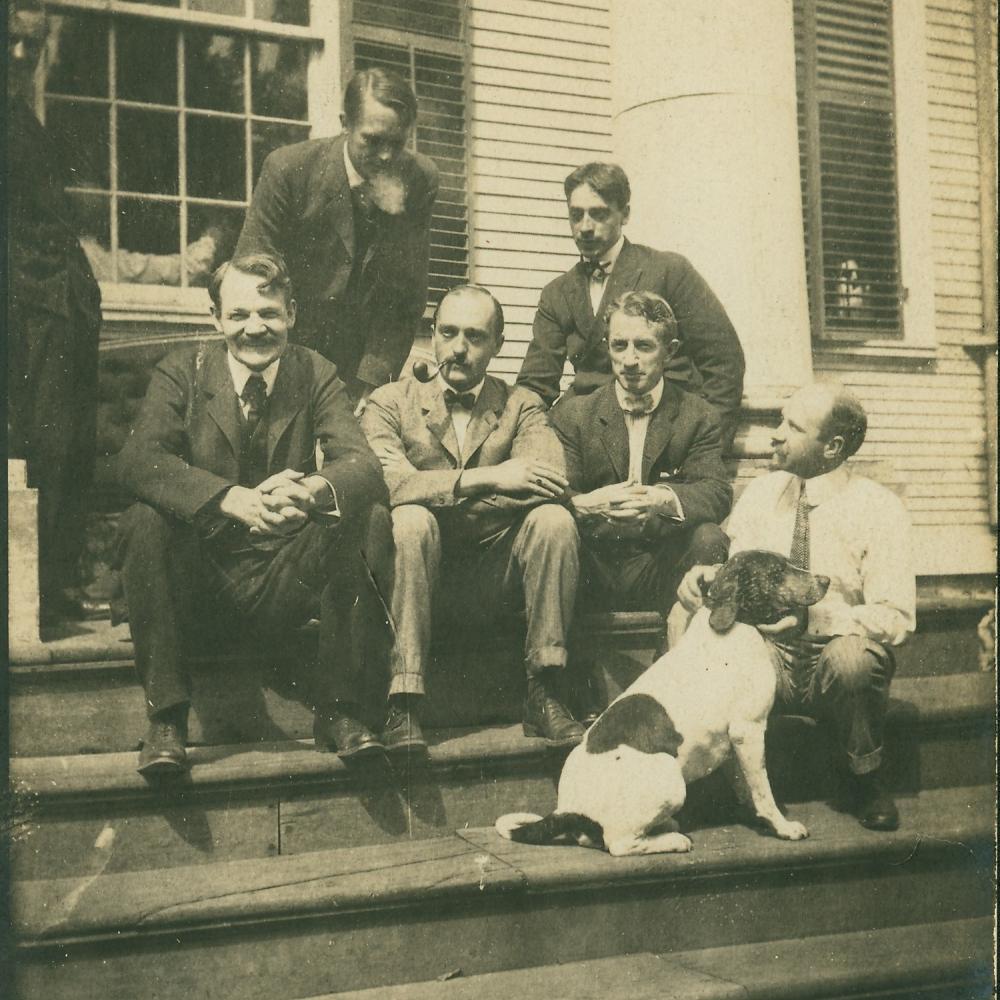

For the next three decades, more than two hundred artists, including a generation of America's finest painters—Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, William Chadwick, and Frank Vincent DuMond—transformed the once staid Griswold family home into a rollicking communal retreat where they exchanged ideas, experimented with with new color palettes, experienced breakthroughs, and produced some of their best work.

The artists' haven has been restored to its appearance circa 1910, the time of the colony's greatest popularity. In the preservation, says Andersen, “we wanted to tell the story of an artist colony and capture its spirit. The house is now humanized. It's not the first or only artist colony in America, but there is a richness here.”

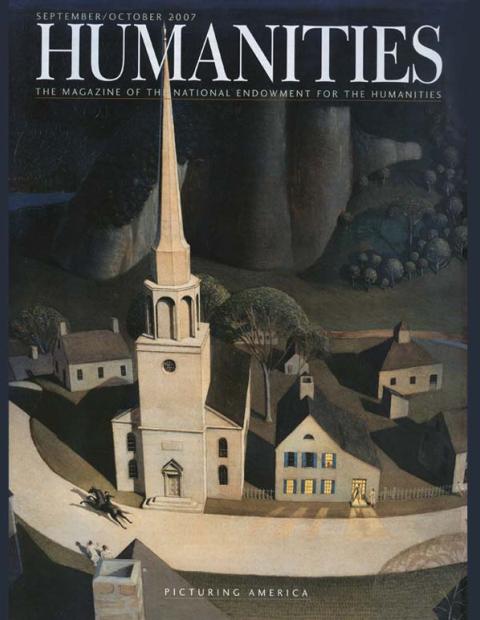

The town and the house inspired major paintings: Ranger's Connecticut Woods, 1899, and Bradbury's Mill Pond, no. 2, 1903, currently in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.; Hassam's Church at Old Lyme, Connecticut, 1905, on display at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo; Metcalf's Dogwood Blossoms, 1906, at the Florence Griswold Museum; and May Night, 1906, at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

“May Night, a moonlit scene of the front of the Griswold House, made Metcalf's career,” says Amy Kurtz Lansing, curator of the Florence Griswold Museum. Before exhibiting May Night, Metcalf offered it to Florence as payment for his board. ”I won't take it,” she is said to have replied. "It's the best thing you've ever done. When you show it in New York, they'll snap it up at once, and everything will be lovely.

In 1907, Metcalf won a gold medal and a $1,000 award from the Corcoran Gallery of Art for May Night. The Corcoran then purchased the painting for $3,000, making it the first contemporary work acquired by the museum. That same year, Lillian Baynes Griffin wrote in the Hartford Courant, “Willard Metcalf sold in three days $8,000 worth of Lyme landscapes in the St. Botolph Club last winter. This made Lyme landscapes sound like Standard Oil, and with no less enthusiasm than the gold hunters of '49, the picture makers have chosen Lyme as a place in which to swarm.”

From revolutionary times through the early nineteenth century, Old Lyme's location near the mouth of the Connecticut River had helped it prosper as a shipbuilding town. Wealthy captains built grand homes like Griswold House. But with the advent of the steamship, the economic tide turned, and Old Lyme fell on hard times, eventually reverting back to its agricultural roots.

“This element of former greatness followed by economic fallowness was ideal for artists to rediscover the area,” says Andersen. “As Miss Florence would say, 'You see, everything savors of the past.' Rural farms, small town churches, early houses—these were all symbols of the American past. In Old Lyme and other New England villages, there was a nobleness and even patriotic quality associated with the gentle, cultivated landscape in which generations of farmers worked the land. Not the wildness of the Hudson School, but a place where man and nature coexisted in harmony. Ranger called it, 'a humanized landscape.' Where the artists, and, not coincidentally, city collectors, and patrons, could reconnect with their American roots.”

As a descendant of one of Old Lyme's founding families, Florence was deeply rooted in the town. One of four children, she was born on Christmas Day, 1850, and raised in the town's finest house. Her ancestors included two Connecticut governors, one of whom, Florence's grandfather, was also a United States congressman and a Connecticut Supreme Court judge. After the Civil War, the Griswolds suffered an economic reversal. In the late 1890s, Florence found herself nearly fifty years old, unmarried, and solely responsible for the upkeep of her home. To make ends meet, she turned her home—which she inherited along with debt—into a boardinghouse. Taking in boarders was a common and socially acceptable occupation for women at the time.

“Florence was especially suited to manage a boardinghouse for artists,” says Andersen. “She was a complex figure. She came out of the Victorian age of manners and bridged the twentieth century. She saw a lot of change and was open to the idea of fostering a colony. She housed bohemian artists, yet was anti-suffragette. She could turn a blind eye to the artists' antics, while other times, was an instigator. She was well-educated, worldly, and was able to lead conversations at the dinner table with a group of artists whose lives extended beyond the region. And she was unfailingly optimistic, each year proclaiming, 'I'm going to have a wonderful season this summer.' She was also trained to be a gracious hostess, knowledgeable about horticulture and read extensively about gardens, and knew French. There was a worldliness to her, yet Old Lyme was her world as well.”

The first artists that stayed at the Griswold House painted in a style called Tonalism, named for their limited and “moody” color palette, popular in America at the time. As early as 1901, the artists began identifying themselves as the “School of Lyme.”

In 1902, fourteen Old Lyme paintings were shown at the National Academy of Design in New York. That summer, the group began exhibiting their work in Old Lyme's library. “The artists planned their first exhibition as a way of showing the town what the influx of painters was up to and to raise money for the benefit of the town's library,” says Kurtz Lansing.

Among the paintings exhibited were Ranger's Moonlight and Autumn Woods, Lewis Cohen's Golden Spring, and William Henry Howe's Truants, a painting of cattle drinking at a brook. DuMond sold The Sighing Wood for $850. The local newspaper reported, “Pictures painted in the town loaned for worthy cause and much admired.”

Considered America's first summer art show, the annual event attracted the attention of national newspapers. Art lovers, critics, dealers, and students hungry to learn from these new American masters flocked to Old Lyme. Quickly, Old Lyme became one of the largest and most influential art colonies in the nation, attracting public figures like Woodrow Wilson and his first wife, the artist Ellen Axson Wilson, who often spent summers at the Griswold House.

In 1903, Hassam arrived. Already recognized as a leader of American Impressionism, Hassam introduced the bright palette of the French Impressionists to the colony. Hassam's presence drew other Impressionists, such as Metcalf, to Old Lyme. Shortly thereafter, Ranger and the Tonalists moved on, and the colony's focus shifted to Impressionism, and the Griswold House became known as the home of American Impressionism.

Artists at the colony watched each other paint, often incorporating new techniques into their own work. Walter Griffin, for example, was already an accomplished artist and teacher when he came to Old Lyme, yet he experienced a breakthrough after his contact with the other artists, according to Kurtz Lansing. “After seeing Hassam and Metcalf paint, Griffin absorbed their brushwork and attention to light. When he exhibited these studies in 1908, one critic remarked: 'The artist seems to feel his way at the point of the crayon here, there, and yonder over the paper until out of these hundreds of lightly traced, suggestive lines comes something of the brilliant, confused, vibrating charm of nature in sunlight.' Similarly, Metcalf hadn't liked working in pastel. Seeing what Griffin was doing, he experimented with the medium. His Lyme Hillside, 1906, shows his great success working with pastels.”

During the day, artists living at the house would pack their paint boxes, stools, sun umbrellas, and portable easels and walk, bike, or have oxen carry their supplies to their favorite sketching grounds. Or they might take one of the row boats—christened The Smallpox, Prickly Heat, and The Scarlet Fever—out on the river. For those who preferred to work indoors, barns and outbuildings were converted into makeshift studios. It was, as Hassam said, “just the place for high thinking and low living.”

When not working, the artists would fish, collect bird eggs, or play practical jokes on each other. Some days they would play horseshoes, ping pong, and baseball, or hold track and field events awarding paper medals for such events as the “fat man” race, in which the generously proportioned Ranger was a regular contestant. One of the colony's festive rituals was captured by Harry Hoffman in Harvest Moon Walk, 1912. Kurt Lansing describes the artists' autumnal celebrations: “On an October evening, merrymakers arrived at Florence Griswold's house imaginatively costumed as fruits and vegetables. The marchers, a mix of artists and townspeople, formed a motley procession. They lit Japanese lanterns and paraded through Old Lyme, accompanied by a band. Once they reached the top of Chadwick Hill, bonfires were ignited and the revelers danced and picnicked by the light of the harvest moon. Although it is not known precisely which year's procession Hoffman pictures in Harvest Moon Walk, a 1916 newspaper describes the costumes of several past and present residents of the boardinghouse: Miss Florence Griswold, string bean; H. R. Poore, 'dead beet;' Clark Voorhees, lettuce; Mrs. Voorhees and Mrs. DuMond, aster; Mr. and Mrs. Harry Hoffman, Dutch tulips.”

In the evenings, everyone would gather in the dining room. After some dinner and conversation, the residents would play cards, hold spelling bees, perform magic tricks, or engage in a game of “wiggle,” which began with an artist drawing a couple of lines on paper, then passing it to another who was required to turn it into a picture.

In warm weather, Florence and a group of artists, including Metcalf, Arthur Heming, Poore, Hoffman, and Katherine Langhorne Adams, would take their meals on the side porch, calling themselves the “Hot Air Club” for their loud and lively discussions on art and other subjects. According to Kurtz Lansing, Poore, who had written an art manual called Pictorial Composition, lectured the other artists about how the composition of every painting should have an entrance and an exit. When Poore began criticizing William Robinson, Kurtz Lanzing says, Robinson responded with “Poore, there is something I am going to tell you: Whenever the fellows want a real good laugh, they just go and read your book.

“The colony had a dynamic quality, and despite petty jealousies and occasional controversies, the artists were, for the most part, admirers and supporters of each other's work,” says Andersen. “But without question, Florence was the central figure. Her relationship with these artists, individually and collectively, sustained the popularity of the colony. She had the ability to have fun, but would keep things at a level where civility ruled. This was her life's work and the artists treated her with great fondness and regard.”

One way the artists showed their affection for Florence was by taking turns painting sections of the walls and doors in the house. Sometimes, a group of artists would collaborate on a panel. The tradition began in the summer of 1900 when Ranger painted one panel on his bedroom door with a moonlit scene of Bow Bridge, which could be seen from the house. He then challenged Poore to complete the adjacent panel. Metcalf continued the tradition by inviting artists to paint the paneled walls of the dining room. Being asked to paint a panel was considered a mark of distinction. Over the years, thirty-three artists painted the doors and walls with a variety of subjects, including Lyme landscapes, farm animals, images of the Far East and Venice, and even their beloved Griswold House. All the original panels have been preserved and are on display in the Griswold House.

“The painted panels became our touchstone and guided the restoration,” says Andersen. “During the planning stage, we kept coming back to those doors and walls. We wanted to give people a sense of how and why they were created as part of the story of the colony.”

One of the most elaborate panels is The Fox Chase by Poore, which he began in 1901 and completed in 1905. Nearly nine feet long, the satirical work features many members of the colony dropping their brushes and palettes and running down Lyme Street chasing a fox into the marsh. Each artist is clearly identified by one of their well-known habits or idiosyncrasies.

“Poore depicted each colony member in characteristic pose or attire for easy recognition. Edward Rook, teased by the artists for his preference for large canvases, is nearly obscured by one of his efforts,” says Andersen. “Carleton Wiggins, known for his absent-minded ways, is smoking a pipe, seemingly lost in thought. William Henry Howe is seated at his easel painting a cow that he bought from a local farmer; he thought having his own animal to take into the landscape would be easier than finding cows on the area farms.”

Hassam, with his shirt draped over his easel, stands bare from the waist up, looking at the approaching crowd, adds Andersen. “Seeing the half-nude Hassam, Matilda Browne throws her arms up in shock. Hassam was a hale and hearty fellow with a passion for a daily swim in the ocean. With exposure to the elements, his skin was turned pink; the other artists named a shade in their palette 'Hassam pink.'”

In 1909, Woodrow Wilson had summered in Old Lyme and wrote of the panels, “Miss Florence has taken artists (for whom Lyme is headquarters in this part of the world) in to board in her spacious old house out of mind, and the place is a perfect artistic curiosity shop, the walls and doors of one room, for example, being painted from end to end with landscapes and figures by men of all stamps, most of them now famous.”

The panels quickly became a tourist attraction. In 1914, writer H. S. Adams noted, “So many of the artists have left a visible impress upon it in the way of a painted panel 'for remembrance,' that the old mansion has developed into a show-place of an altogether unique character. Every stranger within the gates of Lyme wants to see it—and to see it is to admire it.”

Miss Florence would show off the panels in informal tours that concluded in the front hall, which she had turned into a gallery. There, she would gently persuade visitors to buy paintings. “Florence was particularly adept at what would now be called the marketing of the colony,” says Andersen. “Out of her enthusiasm and desire to sustain the colony, because of what these artists were creating, she would do everything in her power to help them sell their work and gain public attention. She was savvy in the way she worked with reporters on how the colony and the artists were portrayed across America.”

In 1921, the artists banded together and opened a gallery next door to the house and made Florence its first manager. Artists kept coming to stay with Florence into the 1930s, until her health began failing. In 1937, she said to a reporter, “So you see, at first the artists adopted Lyme, then Lyme adopted the artists, and now, today, Lyme and art are synonymous.” That same year, at eighty-seven years old, Florence died in her family home. Her obituary in the New York Times read "This generous spirit survives; and not in the Griswold house alone, but as part of no inconsiderable chapter in the history of our native art.”

To settle Florence's debts, her house and belongings, everything except the painted panels, were sold at auction. “With the Depression and a new generation of artists, this art was not valued at that time,” says Andersen.

In 1941, the Florence Griswold Association bought the house, and, in 1948, the museum opened.

Artists are still attracted to Old Lyme, and they are often found painting on the same grounds as their predecessors. “A lot of artists continue the tradition of being engaged with the landscape,” says Kurtz Lansing. “What is extraordinary is that American landscape has undergone a tremendous change in many parts of the nation, but here in Old Lyme, painters can still see and paint the landscapes that those earlier artists painted a century ago.”

In Andersen's view, the colony left a legacy. “Here, the artists, Miss Florence, the workers, and the community at large all interacted in this social experiment in a traditional New England town. Here was a group of people showing their individuality while forming a sense of community. Isn't that what American society is all about?”