When we think of England's literary culture during the eighteenth century, we conjure scenes of the sociable world of clubs, coffeehouses, and salons: Dr. Samuel Johnson sharing tea and wit with Oliver Goldsmith at his club; John Dryden lording over the assembly of poets at Will's Coffee House; Lady Mary Wortley Montegu dispensing Turkish coffee and conversation to the London literati in her drawing room. When we think of literary culture in early America, rather different images come to mind: Jonathan Edwards scorching the pulpit with a fire-and-brimstone sermon; Tom Paine churning out Revolutionary manifestoes.

The very idea of the literary salon seems mannered and European. But was cultural life in early British America really so different from that in London, Edinburgh, and Dublin?

The recent publication of the Library of America's American Poetry: The Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries reveals a pre-Revolutionary American literary scene every bit as avid as Great Britain's in its love of artistic sociability. Among the wealth of newly discovered poetry from the colonial era printed in the collection, a substantial portion derives from the manuscripts generated by a constellation of tavern circles, clubs, tea tables, salons, and coteries that graced the major cities of the Atlantic seaboard. This NEH-supported collection brings to light a society of poets whose work dominated nonreligious writing from 1690 to 1776. The great ambition of these writers was to bring into America something more than liberty, salvation, and material wealth. They wished to establish a public culture in which civility and its most pleasurable expressions, the fine arts, flourished.

From Bridgetown, Barbados, to Kittery, Maine, clusters of people gathered together to experience the pleasure that arises when play, wit, singing, social reading, and impromptu versification elevate talk above routine reports on weather, travel, and business. Some groups organized into formal associations with laws and rituals—the Tuesday Club of Annapolis (a group that sometimes fantasized it was a sovereign state), Benjamin Franklin's Junto, the St. Cecelia's Society of Charleston (devotees of music), the Hungarian Club of New York City (Anglos pretending to be Hungarians), the Bow Bell Club in Barbados (every member had to have lived at one time within hearing distance of the bells of St. Mary-le-Bow in London), the Bachelor's Hall Club in Philadelphia (the hall was a wooden clubhouse on the banks of the Schuylkill River). Some were more informal in their structures, confessing a name, perhaps, and a common passion, but little else in the way of regulation, such as the poetic Swains of the Schuylkill, who gathered around Provost William Smith in Pennsylvania, or the country party wits who satirized the politics of Governors Cornbury and Cosby of New York, or the Scots Club of “clamorous malcontents” in Savannah that roiled Georgia's civil peace with verse satires dropped in the street for citizens to read.

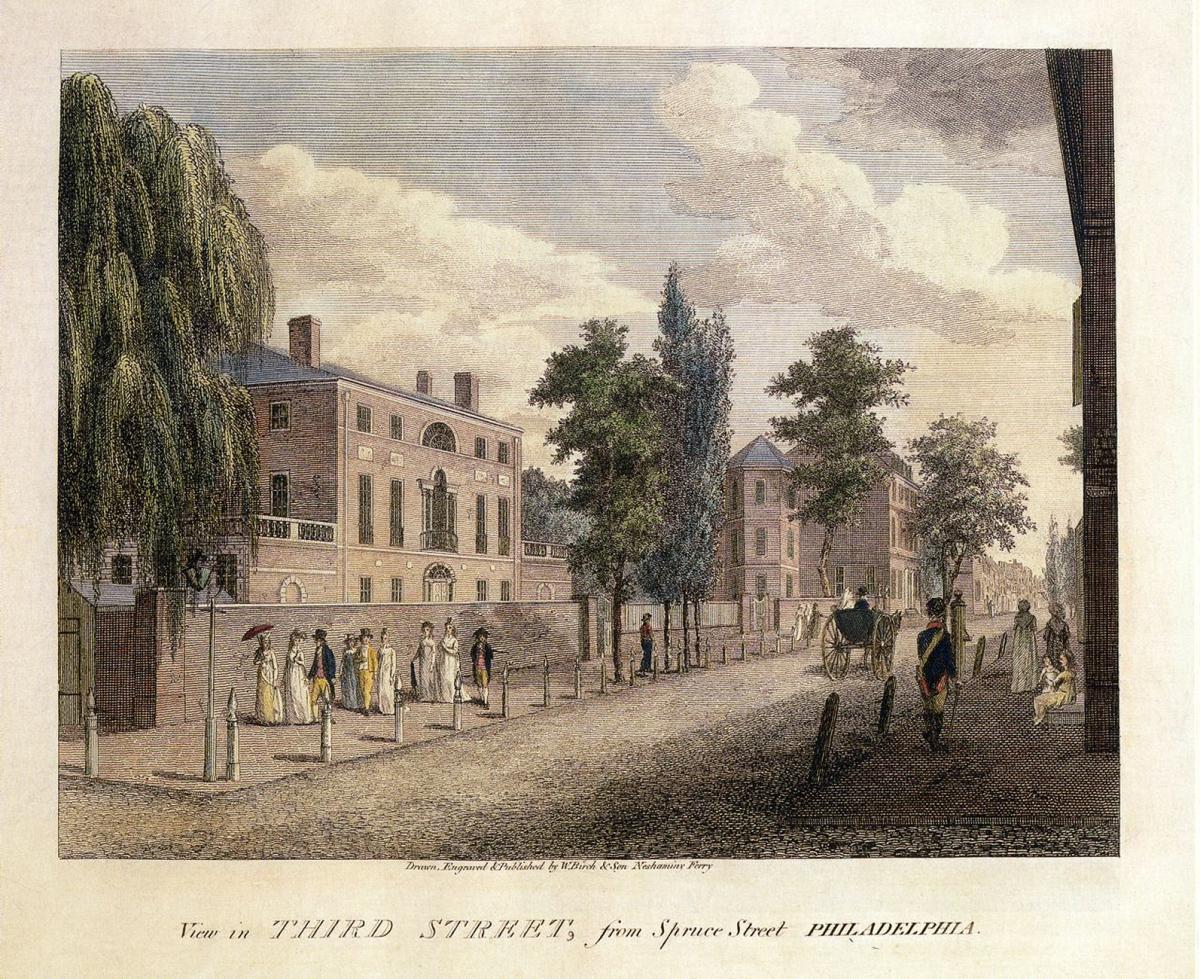

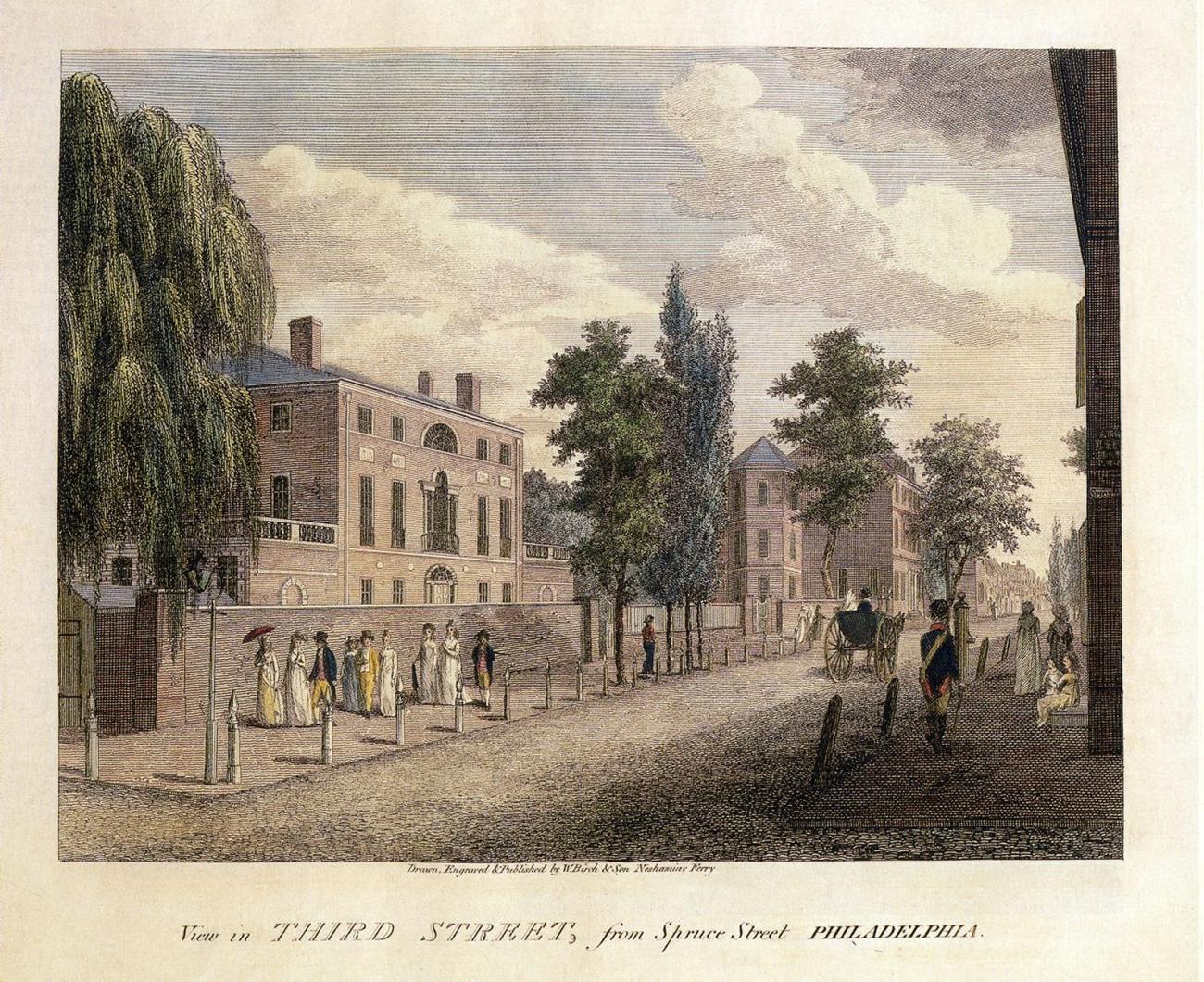

Some of these societies were all-male enclaves, others all-female gatherings, such as Maryland's Syllabub Club or Madam Sarah Kemble Knight's tea table. Early America boasted an ambitious group of salonieres, women who gathered about themselves the cultivated men and women of their neighborhoods to enjoy mutual edification and entertainment. Several of these literary hostesses were accomplished poets, specializing in vers de société, poetry meant to make persons conscious of the joys experienced in community. Margaret Lowther Page, mistress of Rosewell plantation, the greatest of Virginia's great houses, convened a lively round of persons in her parlor and at her Williamsburg townhouse. Elizabeth Graeme hosted Pennsylvania's young literati at her weekly parties in Philadelphia or at her country house, Graeme Park. In the post-Revolutionary period, Anne Willing Bingham (you know her—Miss Liberty on America's early coins) became the arbiter of fashion and intellectual conversation at her style palace, Lansdowne, in Philadelphia. Even Thomas Jefferson, who hated salons in the Parisian mode, felt compelled to attend because the finest minds in the Republic gathered in Mrs. Bingham's parlor. Annis Boudinot Stockton, New Jersey's great saloniere in Princeton, taught Martha Washington how to run a republican court, when hosting the Continental Congress (of which her brother Elias Boudinot was president) at her estate, Morven, in 1781.

All of these groups aimed to enrich society, to make company more stimulating, informative, and sensitive. Aside from this common desire for enrichment, the ambitions and accomplishments of the groups differed widely. Some-Franklin's Junto for instance or the King's College Club in New York City—sought to improve the skills of the members in thinking and speaking as preparation for public life. Others sought to deepen friendship through the cultivation of good humor, such as the Ugly Club of Charleston (a gentlemen's club for those with no pretenses to grace, face, or fashionability). Some cultivated sense and learning, such as the Winyah Indigo Society in South Carolina. But the most ambitious sought to create art from their interactions. At one time or another at least one of these aspiring companies operated in every city in early America. To grasp what some of these circles accomplished artistically, we should take a look at the doings of one circle, the coterie that formed around the young secretary of colonial New Jersey, Archibald Home.

The group that formed around Home was a coterie—an irregular aggregation that would meet at various places (New York City and Trenton in Home's case). All were devotees of poetry, and all recognized Home as a master of versification. Coteries formed in a number of colonies around arch-poets. Aquila Rose, an English printer who went to sea because of a broken heart, landed in Philadelphia and became the charismatic focus of the city's young literary men. Thomas Dale exercised a similar fascination in Charleston, Henry Brooke in Newcastle, Delaware, Governor Robert Hunter in New York City, Mather Byles in Boston, and Oliver Wolcott in Connecticut. One token of the power of the figures at the center of coteries was that their writings would be preserved by their followers and often gathered posthumously. Home died in 1744. Abigail Streete Coxe, his successor as head of the coterie, collected his verse and had a scrivener prepare an elaborate manuscript edition of Poems on Several Occasions by Archibald Home. Esqr. Late Secretary, and one of His Majestie's Council for the Provinces of New Jersey, North America. Copies were distributed on both sides of the Atlantic. Only two copies survived into the twentieth century. One burnt up in the great fire of Patterson, New Jersey, in 1902. I discovered the second in the Laing Manuscripts at the University of Edinburgh Library in 1991.

The manuscript gives a fascinating glimpse into the practices of the early literary circles. It collects the work of several members of the coterie as well as Home's verse, noting Home's corrections to every member's writings as well as his own to emphasize his role as a self-critical mentor in the arts. The members of the circle included Moses and Richa Franks, the cultured offspring of British America's wealthiest Jewish merchant family; Joseph Worrell, New Jersey's attorney general; David Martin, Trenton's sheriff; Robert Hunter Morris, son of New Jersey's governor and member (with Home) of the Provincial Council; Abigail Streete Coxe, wife of wealthy landowner Daniel Coxe and New Jersey's leading female savant; and George Emmott, lawyer and clerk of Elizabethtown. Like upper-class English belletristic circles, Home's group played at having alter egos, classical identities with poetic names. Abigail Coxe was Emilia, Richa was Flavia, Home was Florio. Fantasizing about being Greek shepherds and shepherdesses had been a favorite form of aristocratic play in England ever since Thomas Wyatt enticed members of King Henry's VIII's royal court to pretend they were ancient pastoralists. Elite men and women found expressing thoughts and feelings under another name enabled them to express freely the deepest impulses of their imaginations. In Home's case, it permitted him to communicate his love for Richa Franks, a love incapable of consummation in the real world. Richa, after the elopement of her older sister Phila with gentile Oliver DeLancey, had promised her mother, Abigail, that she would not marry a Christian. Florio courted Flavia and conjured a classical never-never land where Jew and Christian were not categories that mattered. In this poetic haven Florio could praise Flavia and communicate precisely those qualities of attention and fancy that distinguish lovers from suitors.

Were now the Gods as heretofore

Willing to grant what we implore

Pygmalion like I'd crave a wife

Kneel down and pray her into Life—Praxiteles of old, 'tis said,

The Queen of Love so well pourtray'd

Each part so like that he to take it

Must as she Swore, have seen her naked.Yet not this work of that fam'd hand

To give the Shape Divine should Stand.

Nor Knellers Beauty's lend a Grace

To Furnish out the Lovely Face.Each Charm from Flavia should be stole

She, only She, can boast the whole:

And would commiserating Jove

Infuse a Soul like hers I love

Second in Bliss to Him alone I'd live

To whom the God's Lov'd Flavia's self should give.

Home's fantasia on the Greek story of Pygmalion celebrated Flavia/Richa in the highest terms—as a natural being so splendid that art offered no improvement—while communicating his ambition to have her as “a wife.” Richa knew the classical myths about artistic creation; they were part of the pedagogy of the fine arts in the English-speaking world, and Richa and her brother studied drawing and painting with Alexander and Quenten Malcom in New York City. Home in the poem showed his knowledge of the pictorial arts, alluding to Sir Geoffrey Kneller, court painter to King Charles II. Even that master could not add to Flavia's graces.

Flavia may have smiled upon Florio in the special precinct of art, but Richa Franks regretfully declined Archibald Home's proposals of marriage. Home's disappointment did, however, lead to a series of epigrammatic complaints about life with a wife and a sardonic masterpiece, “The Black Joke,” a ribald meditation on the divine jest of sexual attraction, responsible for “The various ills that have happen'd to Man . . . Since this World began.

”After Home's death in 1744 Richa remained unmarried, leaving America to live with her brother David in London as a spinster.

Misery may love company, but company does not love misery. Coterie life thrived on humor, on pleasantry, on play, and on shared aesthetic experiences. Love is, and was, not a game. So Home put aside love and its miseries and celebrated the diversions that gave relish to life, particularly life in company. Home, in a poetic riddle, commented on the ubiquity of cards in feminine company. Two of his epigrams suggest that singing was a common company experience. In reply to a request that he sing, because it was said he sang as beautifully as the castrato Farinelli, Home denied having Farinelli's voice, but confessed he had something Farinelli lacked that could supply other sorts of stimulation.

The other great source of shared pleasure besides play was poetry. On the occasions when the company met in a member's home, verses were read aloud and critiqued. This was no elementary education in the art of versification; they played no rhyming games, such as crambo, the pass-and-complete-the-couplet elimination contest once popular in American colleges. Home's manuscript suggests that poems came into the conversation of the coterie in three ways: some sprang impromptu from the lips, a short spontaneous effusion of wit; some were composed as song lyrics to be performed by members of the company (these assumed a ritual place in the meetings, being repeated as occasion suited); and some were works of art, composed by a coterie member in private, brought before the company, read, and critiqued. They were then given to Home, who would correct the pieces, rereading them at a subsequent meeting.

Among the coterie poems included in the Home manuscript, several belong to the young Moses Franks. When Home first arrived in New York in 1733, he joined, as most well-bred immigrants in colonial cities did, a club of his countrymen, in Home's case, the St. Andrew's Society. There he met schoolmaster Quenten Malcom. Malcom at that time was instructing the Franks children in violin playing, painting on glass, bookkeeping, and Latin. Malcom introduced Moses and Richa to Home as his prize pupils, and the fashionable young Scot took upon himself the task of finishing them in the muses. Moses desired to master poetry and his reverence for his instructor can be read in the funeral elegy he wrote for Home in 1744. It is Franks's only poem in the manuscript that doesn't bear the marks of Home's instructing pencil. Its smoothness, conceptual ingenuity, and feeling attest to his teacher's effectiveness.

TO THE MEMORY OF ARCHIBALD HOME ESQR.

O Thou! For whom each Muse with fondness wove

The choisest Garlands from the Thespian Grove,

Touch'd thy bright Mind with Force divine Strong

And tun'd thy Soul, and harmoniz'd thy Song,

Blending with these, whate're Mankind could boast

To make Thee honour'd lov'd and value'd most.

Could Sparkling Wit the blest Possessor Save,

Or awful virtue shelter from the Grave

This plaintive Verse had ne'er bid Sorrows flow,

Nor the soft Eye confest the tender Woe.

Still had'st Thou liv'd! Earth an evy'd Name

Of our New World, the Wonder Joy and Fame.Can universal Sighs our Woe suspend

Or mitigate the Loss of such a Friend?

Can Tears incessant yield the Wish'd Relief?

Or mournfull accents sooth th'extensive Grief?

In vain! No Sighs allay; no Tears can heal

The Gloomy Anguish, All who knew Thee Feel.Or say if we cou'd rob the Arms of Death

Snatch Thee to Earth restore thy Precious Breath

And for some Moments, to beguile our Pain,

Drag Thee unwillingly to Life again!

Oh no! let no rude Hand thy Peace molest,

Or shake the Calm which now o'er spreads thy Breast.Then take this Verse (if Verse like this is heard)

The last sad Tribute of a Muse Thou rear'd;

And if thro' Time my Artless Labours rise,

My Muse shall hail Thee to Thy Native Skies.

Moses Franks, for all his love of poetry, did not “rise” to artistic renown. Though his youthful verses entitle him to the honor of being the first significant Anglo-American Jewish poet, he fixed himself in popular memory as an immensely influential merchant, overseeing vast enterprises such as provisioning the English Army during the French and Indian War. The glimpses of Franks found in Home's manuscript suggest his later monetary riches were matched by a wealth of soul, an enrichment of the affections and the imagination. These were the rewards of sociable communion in the arts.

Home, though he was the “Wonder Joy and Fame” of the New World in 1744, slipped into that general amnesia about the literature and culture of colonial America that afflicted the United States in the early nineteenth century. Then—when being in print and being well reviewed became the signs of literary merit—all the writers who trafficked in manuscript fell into neglect. Yet the ideals that animated Home and his contemporaries in the sociable world of early America did not and do not deserve contempt. Civility, learning, friendship, and mutual enrichment are necessary to build a community that stands for something other than custom, coincidental interest, or religious orthodoxy. Home's circle typified those private companies that cultivated mutual pleasure, conversation, and artistry in early America while pursuing the enrichment of society.

We may not now regard Society as an ideal or utopian expression of civilization. (And we certainly don't capitalize the word anymore.) But for the most culturally sophisticated early Americans, Society was an ideal. It named that community in which one found insight, pleasure, and emotional fulfillment through conversation and cooperation. Membership in Society was not necessarily predicated on religion, ethnicity, gender, or class. What won a person entrée into its company was a demonstrative desire for civility, an attentiveness to manners, an openness to play and the pleasures of imagination. While the satisfactions of Society could be limited (Society did not secure for Home the bliss of married life with his beloved), within its bounds it offered real benefits (Home could share his hopes and thoughts with his beloved in company). In club and salon poems such as Home's and those of other early American authors in American Poetry: The Seventeenth & Eighteenth Centuries, we see Society made an earthly Elysium, a place where pleasure and people combined.