As city streets throbbed with protests (and what some might call uprisings) during the summer of 2020, two science fiction dramas recalled the massacre of Tulsa, Oklahoma, which took place 100 years ago this spring. Watchmen and Lovecraft Country, both on HBO, filled television screens with imagery of Tulsa’s Black neighborhood of Greenwood—Booker T. Washington nicknamed it Negro Wall Street, which morphed into Black Wall Street—as it was shot up, torched, and bombed from the air by white vigilantes. Viewers wondered if the events depicted were more fiction than science. Social media was abuzz with people trying to find out more about Tulsa. Among African Americans, however, the memory had not completely faded.

Even before Watchmen (which premiered in fall 2019) and Lovecraft Country (fall 2020), Black social media and public lectures promoted the hashtag #BlackWallStreet. In the fall, rapper, activist, and entrepreneur Killer Mike, who extols the values of Black self-determination and independent institution-building, cofounded a Black and Latinx digital bank called Greenwood.

The name Greenwood still evokes the possibilities and history of Black entrepreneurship, but talk of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre reminds the world of the centuries-long struggle of Black people against white mob violence and its greenlighting from white authorities.

A LEGACY OF BLACK INDEPENDENCE

The destruction of Greenwood and the assault on its citizens, beginning on May 31, 1921, was called the worst public disturbance since the Civil War. At the time, Greenwood was very likely the most prosperous Black community in the country, and Tulsa, the “Magic City,” was one of America’s fastest-growing cities, an oil boomtown, following the 1905 discovery of the Glenn Pool Oil Reserve 15 miles south of town.

African Americans had been around Oklahoma for a long time. In The Black Oklahomans, Arthur B. Tolson shows that Africans, both Moors and Angolans, free and enslaved, accompanied Coronado’s expedition, which crossed the Oklahoma panhandle in 1541. William Loren Katz’s Black Indians and Art Burton’s Black, Red, and Deadly cite an early Black presence in Oklahoma, then called “Indian Territory.” Randy Krehbiel’s Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre quotes Washington Irving’s 1835 eyewitness description of the Creeks, which confirms an early Black presence: “quite Oriental in . . . appearance,” and “a sprinkling of trappers, hunters, half-breeds, creoles and negroes of every hue.” Black families, enslaved and freed, were among the Lochapoka Creeks, who were forced from Alabama during the Trail of Tears and founded Tulsa in 1836.

Before emancipation, Blacks enslaved by the Indians fared better than those enslaved by whites. In a 1940 Works Progress Administration oral history, an ex-enslaved Creek confirmed this: “I was eating out of the same pot with the Indians, . . . while they [other enslaved Blacks] was still licking the [white] master’s boots in Texas.” By the turn of the century, an estimated 37 percent of the Creeks were Black—many with land rights.

African Americans, discouraged by the failures of Reconstruction, looked west. Benjamin “Pap” Singleton organized “Exodusters” and founded Nicodemus, Rattle Bone Hollow, Hoggstown, and many other towns in Kansas. By the 1880s, under the leadership of African-American attorney Edwin P. McCabe, a former clerk for the United States Treasury Department, Blacks formed Oklahoma clubs and worked to make Oklahoma an all-Black state. Thousands of African-American families moved in and helped found 30 Black towns, including Boley, Clearview, Tatum, Lima, and Langston, where McCabe himself helped found Langston College in 1897.

Green Currin, who participated in the Oklahoma Land Run of 1889, was elected to the Oklahoma Territorial Legislature in 1890. The only African American in the legislature, Currin authored Oklahoma’s first civil rights bill, which lost ratification by one vote as the territorial government proceeded to disenfranchise Blacks and pass its first Jim Crow laws.

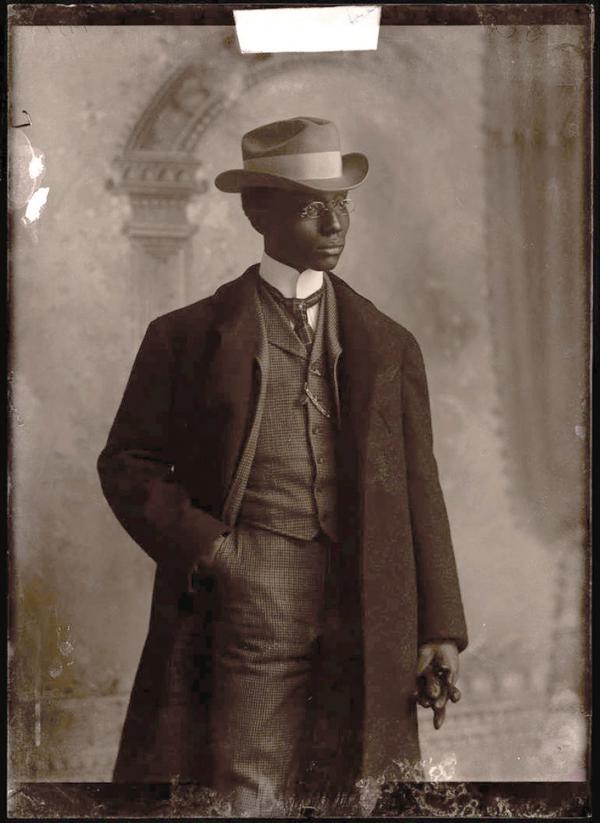

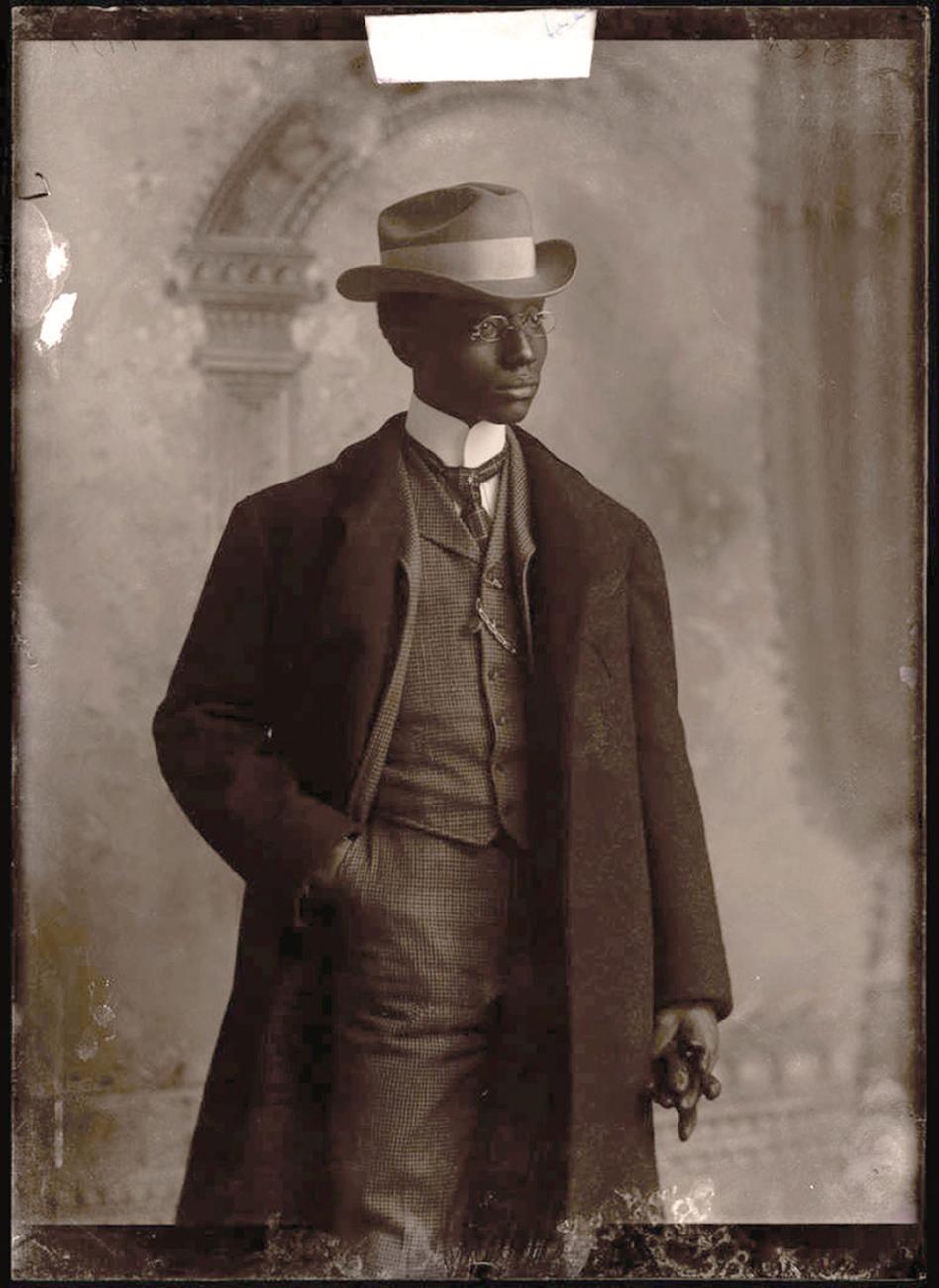

Ottawa W. Gurley (known as “O. W.”) founded the Greenwood District. He was born in Huntsville, Alabama, on Christmas Day in 1868, and educated in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Staking a claim in the Cherokee Outlet Land Run of 1893, Gurley and his wife opened a general store and founded Perry, Oklahoma. When he heard of the Glenn Pool oil strike, Gurley saw opportunity and moved to Tulsa in 1906. He bought land and opened another general store north of Tulsa’s St. Louis and San Francisco or “Frisco” Railroad tracks.

Sidestepping discrimination in the oil industry, Blacks arriving in Tulsa prospered as maids, shoeshines, waiters, chauffeurs, cooks, barbers, mammies, and gardeners to the newly rich. As spending multiplied, some Blacks earned nice salaries—more than many white-collar workers. Black people had money and needed places to spend it. Segregation produced a captive marketplace, and Black entrepreneurs prospered. John Williams, originally from Mississippi, opened an automobile repair shop and then Williams Dreamland Theatre, offering live stage shows and silent films, in addition to the air-conditioned Williams Confectionery. John “the Baptist” Stradford bought properties and stores and completed the 54-room Stradford Hotel in 1918.

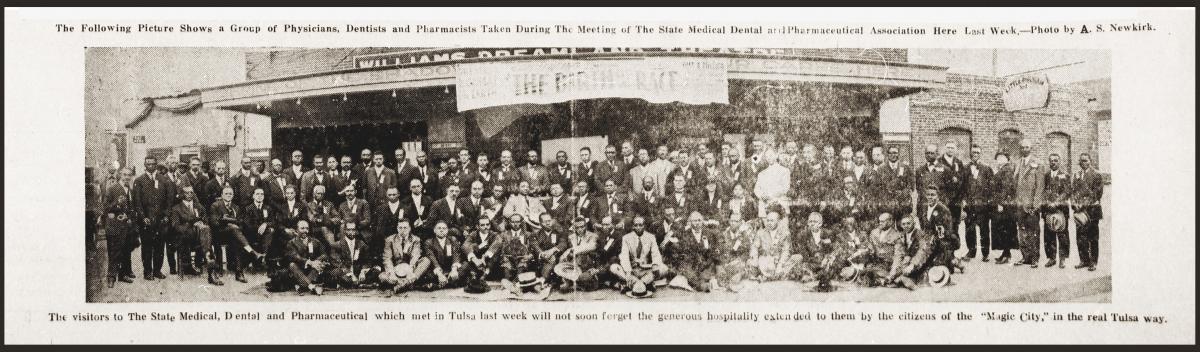

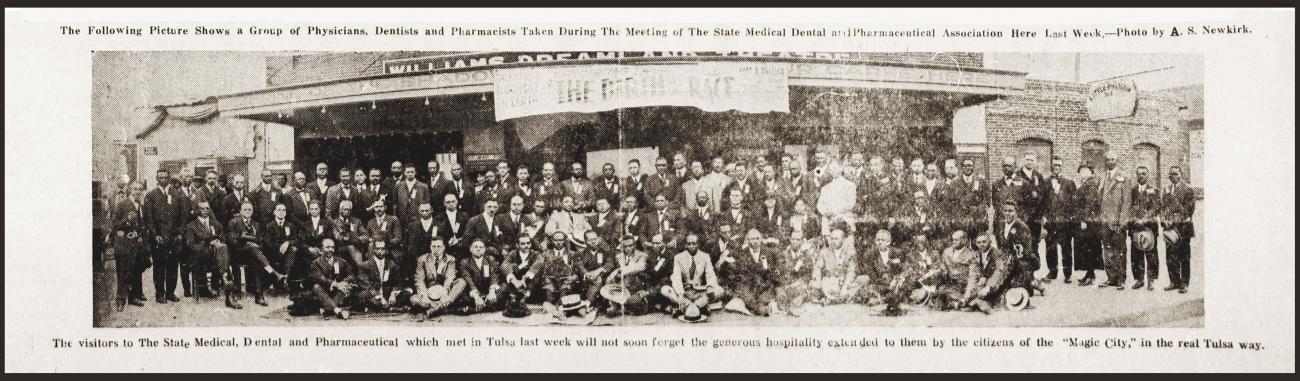

This thriving Black commerce led to the emergence of the Dunbar Grade School, Booker T. Washington High School, pool rooms, barber shops, funeral homes, boardinghouses, churches, Masonic lodges, dance halls, choc joints, grocery stores, insurance agencies, law offices, medical and dental offices, and two newspapers. In just a few years on or near Greenwood and Archer streets, exciting sights, sounds, and smells inspired the captions “The Black Wall Street” and “a regular Monte Carlo.”

As the “Magic City” grew with the steady influx of white settlers and fortune hunters, it became more like the rest of America, but with less law and order. White “mobacrats” employed extralegal tactics to gain an advantage over Blacks, Indians, and even white union organizers. As eleven-year-old Sarah Rector, a member of the Muscogee Creek Nation, became the “Richest colored girl in the world” when a gusher was discovered on her land, many African Americans feared for their lives. Postcards, issued in 1911, featured the hanging of African-American farm wife Laura Nelson and her castrated son from a bridge in Okemah, Oklahoma—an event that later inspired the activism of Woody Guthrie. Another postcard showed the burning of an unidentified Black man in Durant, and was captioned “Coon Cooking.” In 1917, 17 white members of the International Workers of the World were flogged, tarred, feathered, and turned loose on the prairie by Knights of Liberty dressed in black robes and masks. By 1921, according to historian Scott Ellsworth, a revived Tulsa Ku Klux Klan claimed an active membership of 3,200.

THE TRAGEDY OF TULSA

It all started on Monday morning, May 30, 1921, when a nineteen-year-old African-American shoeshine named Dick Rowland was working at a stand in front of the Drexel Building in downtown Tulsa. Rowland went inside the building to use the third-floor segregated restroom. The elevator operator was seventeen-year-old Sarah Page, a white girl. What happened next is still disputed, but Page told the police that Rowland, who had left the scene, grabbed her arm and made her scream.

Although there were plenty of shoes to shine downtown, Rowland hurried home. He told his family that he had tripped over the elevator threshold and accidentally grabbed a white girl and she had screamed. Everyone knew that he should lie low for a while. The next day Rowland was arrested at his home by two Tulsa police officers, one white and the other, Henry Pack, Black.

The Tulsa Tribune then published the front-page headline “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator.” Later, Walter White, who investigated the incident for the NAACP, wondered why so many were willing to believe that Rowland was foolish enough to attack a white girl on an elevator on a holiday during a time of terror.

Tulsa police commissioner J. M. Adkison and police chief John Gustafson were under pressure to keep law and order in the rough and tumble boomtown. Less than a year before, in August 1920, a white drifter, Roy Belton, had been ripped from jail by a white mob and hung in public for killing the town’s favorite cab driver. Also in August 1920, in Oklahoma City, an eighteen-year-old Black youth, Claude Chandler, was lynched by a mob that featured the future mayor of Oklahoma City, O. A. Cargill.

This time, the police, fearing a lynching, moved Rowland from the regular jail to the top floor of the Tulsa County Courthouse for safekeeping. Meanwhile, the Tulsa Tribune’s afternoon edition fanned the flames with the headline “To Lynch Negro Tonight!” as an ugly mob began to gather outside of the Tulsa Courthouse.

As Rowland sat in jail, back at the offices of the Black newspaper, A. J. Smitherman of the Tulsa Star led an impassioned discussion about how to protect him. Smitherman’s Tulsa Star promoted the idea of the “New Negro,” independent and assertive. Smitherman had chastised Blacks for allowing the lynching of Claude Chandler the year before in Oklahoma City, and he urged the men in the room to protect Rowland and themselves.

W.E.B. DuBois had visited Tulsa in March as the NAACP protested the gruesome lynching of Henry Lowery in Arkansas. DuBois had already warned the Black veterans of World War I, in the May 1919 issue of the Crisis, that they would be “cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.”

Later that afternoon at the Black-owned Williams Dreamland Theatre, sixteen-year-old Bill Williams watched as a neighbor jumped on stage and announced: “We’re not going to let this happen. We’re going to go downtown and stop this lynching.” True to their word, an armed contingent of 25 Black men went to the Tulsa County Courthouse. Led by O. B. Mann, of Mann Brothers Grocery Store, and Black Deputy County Sheriff J. K. Smitherman (A. J.’s brother), they offered their assistance to Sheriff Willard McCullough, but he persuaded them to leave.

As the white mob reached nearly a thousand, a new contingent of 50 or more Black men, feeling anxious, arrived to protect Rowland, but they, too, were persuaded to leave at about 10:30 p.m. Then, as they walked away—according to Scott Ellsworth’s interview with seventy-eight-year-old survivor Robert Fairchild—E. S. MacQueen, a bailiff and failed candidate for sheriff, grabbed a tall Black man’s .45-caliber Army-issue handgun, leading to this exchange:

“N—, where are you going with that pistol?”

“I’m going to use it, if I have to” was the retort.

“No, you give it to me!”

“Like hell I will!”

Then according to several chroniclers, “all hell broke loose,” as the mob engaged the retreating Black men in a pitched gun battle that inched its way north toward the Frisco Railroad tracks that separated downtown from Deep Greenwood. The mob broke into downtown (white-owned) pawnshops and hardware stores to steal weapons and bullets. Tulsa law enforcement deputized and armed certain members of the mob. A disguised light-skinned African-American Tulsan overheard an ad hoc meeting of city officials plan a Greenwood invasion that night. Sheriff McCullough, hunkered down in the County Court House, kept Dick Rowland safe as the mob’s fury was aimed at a Negro revolt in Greenwood. While most mob members were not deputized, the general feeling was that they were acting under the protection of the government. The fact that after the disaster none of them were convicted of crimes vindicates that position.

After an all-night battle on the Frisco Tracks, many residents of Greenwood were taken by surprise as bullets ripped through the walls of their homes in the predawn hours. Biplanes dropped fiery turpentine bombs from the night skies onto their rooftops—the first aerial bombing of an American city in history. A furious mob of thousands of white men then surged over Black homes, killing, destroying, and snatching everything from dining room furniture to piggy banks. Arsonists reportedly waited for white women to fill bags with household loot before setting homes on fire. Tulsa police officers were identified by eyewitnesses as setting fire to Black homes, shooting residents and stealing. Eyewitnesses saw women being chased from their homes naked—some with babies in their arms—as volleys of shots were fired at them. Several Black people were tied to cars and dragged through the streets.

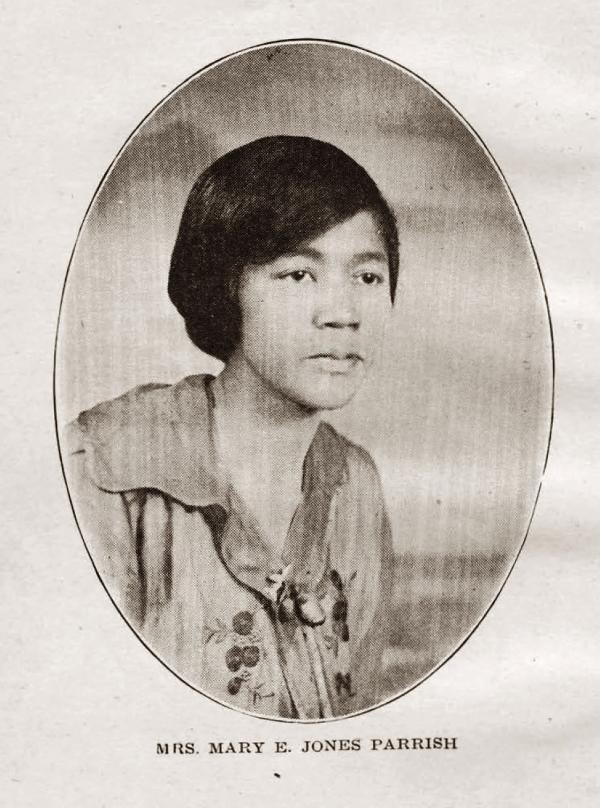

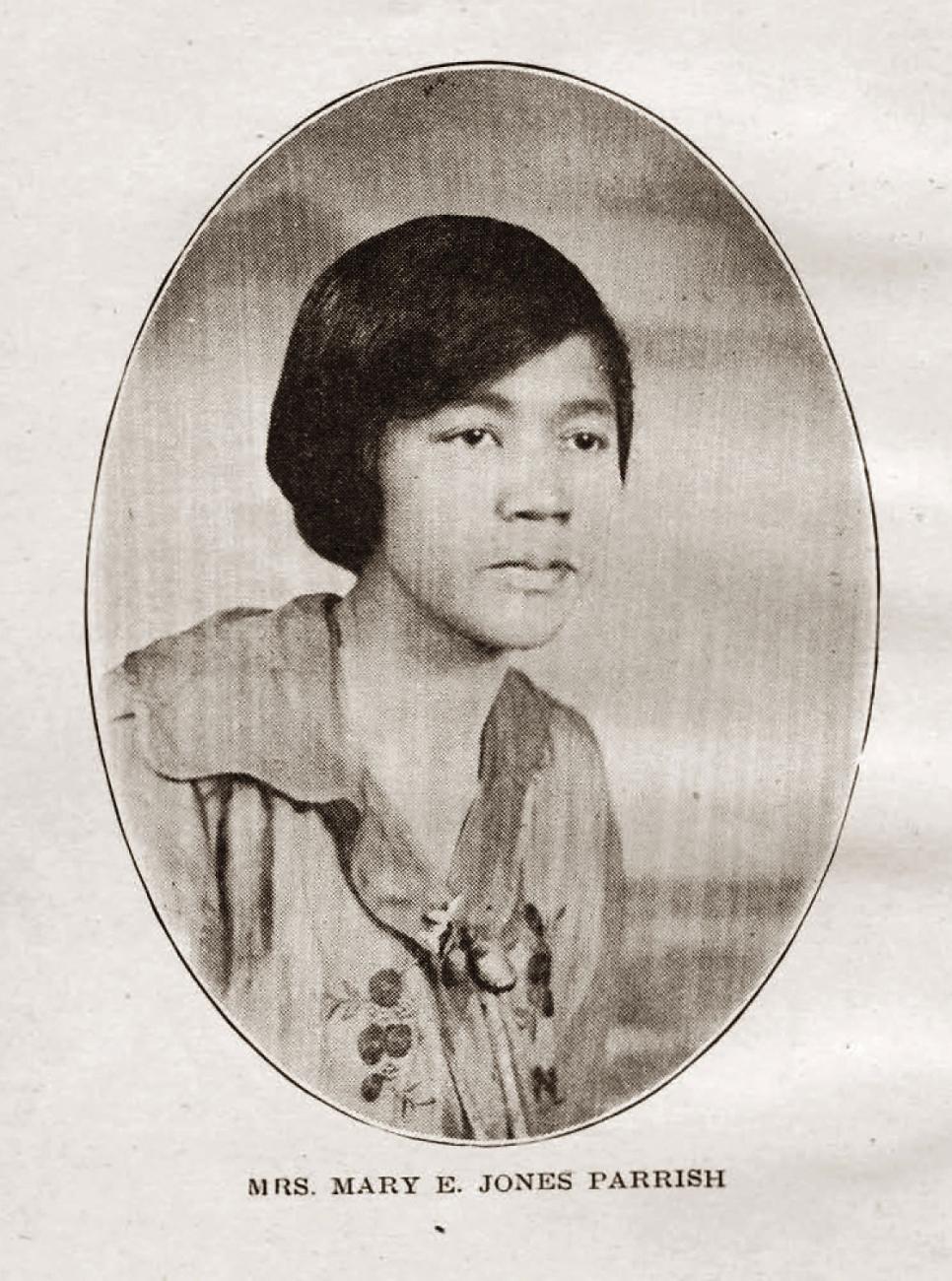

The Black residents of Greenwood did not passively endure the onslaught. Mary E. Jones Parrish said that the Greenwood men defended the Frisco Tracks like “a stone wall,” until they exhausted their ammunition. O. B. Mann, a WWI veteran and veritable giant, led a valiant fight by sniping the rioters from Mt. Zion Baptist Church’s bell tower until the church was engulfed in flames. A Greenwood legend, “Peg Leg” Taylor, a veteran of the Spanish-American War, was said to have shot a dozen white men from a sniper position on Standpipe Hill. Both survived the conflict.

The Oklahoma National Guard, called in by the governor to restore order, did so by joining the fray against the outnumbered and outgunned Black community. The Guard helped round up and disarm at least four thousand African Americans—men, women, and children—and marched them at gunpoint to makeshift detention camps at the Tulsa Convention Center and the McNulty Baseball Park as the mob in the early hours looted their homes.

The looting, though hurried, was methodical, with mobsters taking furniture, Victrolas, and pianos. Over the course of three days, dead bodies were stacked up on trucks and railroad cars and buried in secret around the city by white aggressors. Even afterward, few Black families had a chance to organize a funeral or mourn their dead. Many Black Tulsans simply disappeared.

Tulsa’s Greenwood Cultural Center tabulates that in the span of 24 hours 35 city blocks of Black Wall Street were burned to the ground. The white mob blocked firefighters while 1,256 homes were destroyed and another 400 were looted. A massive share of people in Greenwood were left homeless. The destruction also included many businesses and community institutions: four hotels, eight churches, seven grocery stores, two Black hospitals, two candy stores, two pool halls, two Masonic lodges, real estate offices, undertakers, barber and beauty shops, doctors’ offices, drugstores, auto garages, and choc joints.

Oklahoma’s Tulsa Race Massacre Commission reported that 100 to 300 people were killed, though the real number might be even higher. “There’s really no way of knowing exactly how many people died. We know that there were several thousand unaccounted for,” Mechelle Brown, program coordinator for the Greenwood Cultural Center, told CNN during a 2016 interview.

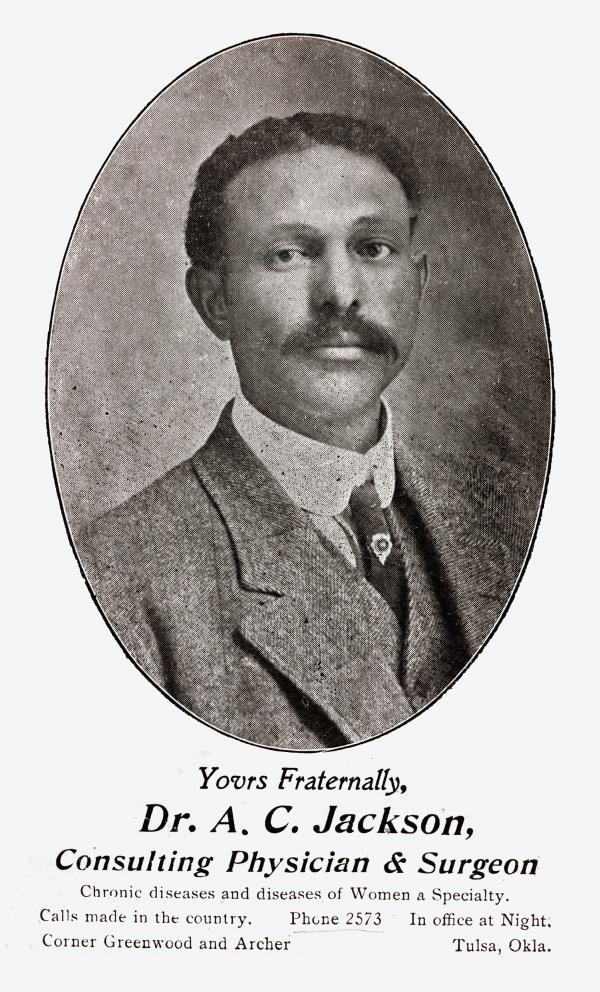

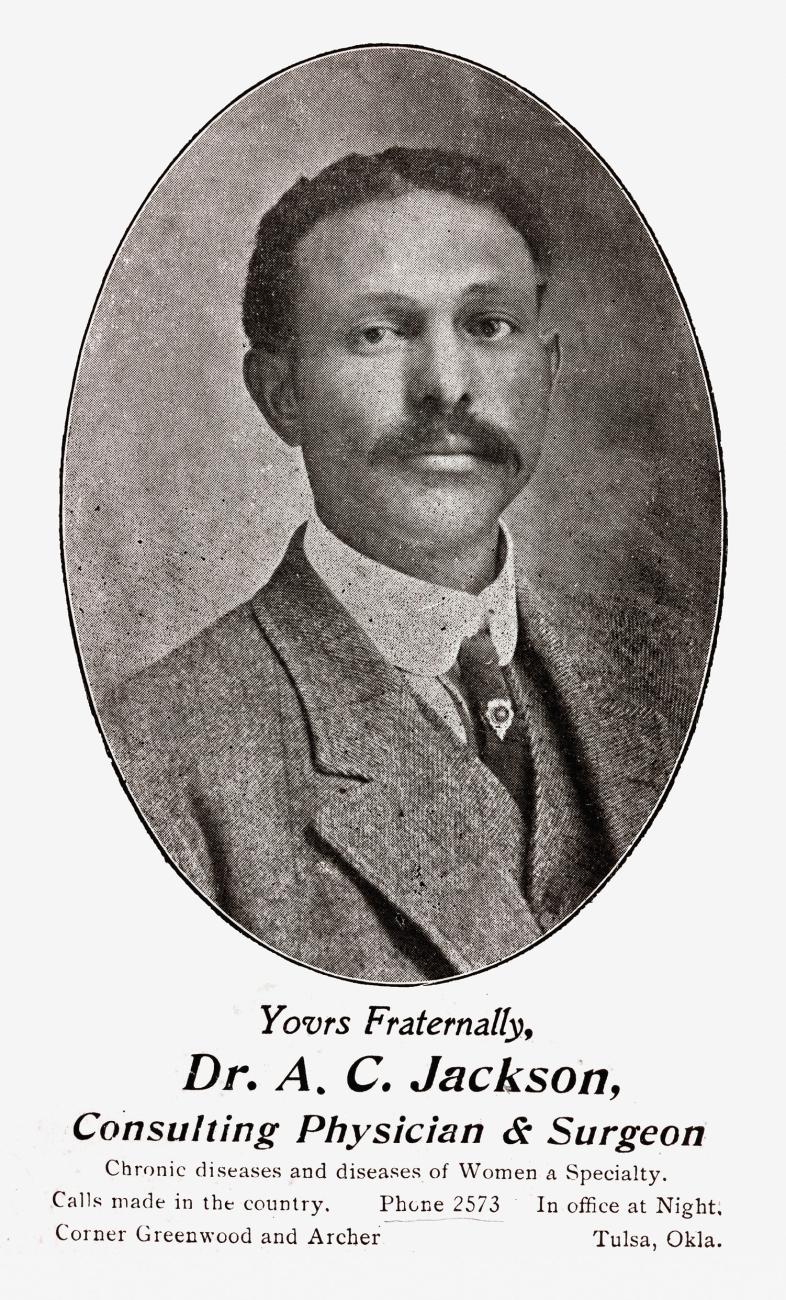

Details are difficult to gather, because many survivors of the massacre fled the city. Among the counted dead was Dr. A. C. Jackson, a noted surgeon endorsed by the Mayo Clinic (the clinic acknowledged his prominence). Late in the battle as gunfire was sporadic, Jackson walked back to his home, after attending to victims, with his hands up. According to Tim Madigan’s The Burning: Massacre, Destruction, and the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, retired white Judge John Oliphant, Jackson’s neighbor, testified that two young men trained their guns on the physician. “Here I am,” said Jackson. “Take me.” “Don’t shoot him! That’s Dr. Jackson,” yelled Oliphant. It was too late. Some still unidentified men in khakis, who come up frequently in the testimony, looked down and asked, “Are you Dr. Jackson?” Learning it was, indeed, Dr. Jackson on the ground, one of them said, “Oh shit, those boys have done it now!”

RESILIENCE

Although they had survived one of the deadliest race massacres in U.S. history and their district was demolished, many residents returned. And they mustered the strength to rebuild. Relief was sent in from around the country, from the Red Cross, churches, and other philanthropies, though Tulsa city officials attempted to block it.

True deliverance for the people of Greenwood, however, came from within, as documented in their own record of the massacre and its aftermath. The story of Tulsa’s Greenwood community, Events of the Tulsa Disaster was compiled by the Black stenographer Mary E. Jones Parrish and published by the Black community sometime after 1922. The book contains first-person accounts of survivors, but it is said that only two dozen copies were printed. Parrish, who miraculously escaped death as she fled through a hail of gunfire with her young daughter, wrote:

The Tulsa disaster has taught great lessons to all of us, has dissipated some of our false creeds, and has revealed to us verities of which we were oblivious. The most significant lesson it has taught me is that the love of race is the deepest feeling rooted in our being. . . . Every Negro was afforded the same treatment, regardless of his education or advantages. A Negro was a Negro on that day and was forced to march with his hands up for blocks. What does this teach? It should teach us to “Look Up, Lift Up and Lend a Helping Hand,” and remember that we cannot rise higher than our weakest brother.

A Mississippi native who had come to Tulsa via Rochester, Parrish has disappeared from the record. But the ethos and bond that empowered residents to rebuild the community was strong. The law firm of Spears, Franklin & Chappelle provided legal assistance to victims. These African-American lawyers filed claims against the city of Tulsa and against its new Fire Ordinance No. 2156, which would prevent most of the victims from rebuilding and the insurance companies from paying for damage caused by the massacre, even as white pawnshop and hardware store owners were compensated for damages to their shops. The lawyer leading the charge was Buck Colbert Franklin, the father of famed historian John Hope Franklin, the late professor emeritus at Duke University. He did not find evidence that the disaster was premeditated by city officials, but he thought they certainly took advantage of it to the detriment of the Black community.

In 1925, Booker T. Washington’s National Negro Business League held its annual meeting in Tulsa’s partially restored business district. By 1942, over 200 Black businesses were operating in Greenwood. It would take the usual suspects—urban renewal, the interstate highway system, and economic integration—to sap the economy and choke the vibrancy of Deep Greenwood.

During this 2021 centennial of the Tulsa disaster we are reminded of the shameful legacy of white racism in Tulsa and other Black communities not that long ago. For many years white Tulsans tried to forget what happened, but it’s much harder for the residents of Greenwood. For Black people, Greenwood is a reminder of the need to stay vigilant.

Other historical acts of racist terror—mob attacks on Black communities in Detroit, Cincinnati, Dayton, and New York—occurred prior to the Civil War. Post-Civil War massacres in New Orleans, Memphis, Wilmington, Charleston, the Atlanta, Georgia, massacre (1906), the Elaine, Arkansas, massacre (1919), and the Rosewood, Florida, massacre (1923) have been buried deep in the record, ignored in mainstream history books, and lost to national memory. Only in 2020, 99 years after the fact, did the Greenwood massacre become part of the Oklahoma school curriculum!

Now that Tulsa has scratched its way into popular culture, it stands as a symbol of Black tragedy and also of resurrection and resilience. The Bloomberg Philanthropies gave Tulsa $1 million for an expansive public art project called the Greenwood Art Project. Quraysh Ali Lansana, an Oklahoma native and the acting director of the Center for Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation at Oklahoma State University, Tulsa, is helping organize an exhibition about the historic Black Wall Street neighborhood, its destruction and its rebirth, for Tulsa’s Philbrook Museum of Art with Tri-City Collective. The exhibition will feature 33 Oklahoma-based artists. Lansana, who has also authored a children’s book, Opal’s Greenwood Oasis, is quick to point out the scars and hurdles that continue to plague Tulsa:

The legacy of Oklahoma is that the place remains deeply segregated, even today. In North Tulsa, where Greenwood was located, there is not a hospital and there has not been one there since the massacre. The difference in mortality rate in North Tulsa is 11 percent fewer years than whites in South Tulsa. The first grocery store since the 1940s or 1950s is just now under construction in North Tulsa! . . . Every year the Tulsa Equality Indicator report comes out and it reveals and outlines alarming disparities along racial lines from policing to the life expectancy.

Historians tend to de-emphasize the violence waged against Black people in America—Tulsa is one prominent example. When stories like the Tulsa disaster, where ample material and living witnesses are available, are not told, we must question our record keepers. In many ways, it is poetic irony that science fiction has forced America to confront its very real history.