On the evening of January 23, 1906, in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Nevada Taylor bundled herself up against the winter cold before leaving W. W. Brooks grocery store, where she worked as a bookkeeper. The twenty-one-year-old blonde caught one of the city’s electric trolleys, paying three cents for a twenty-minute ride to St. Elmo, a small community at the foot of Lookout Mountain. Her father worked as the groundskeeper at the Forrest Hills Cemetery and the family lived in a cottage on the property.

Around 6:30 p.m., the trolley dropped Taylor off at Cemetery Station, two and a half blocks from her home. The weak winter sun had retreated behind Lookout Mountain, and there were few streetlights in that part of the city to dissipate the gloom. Shadows and darkness surrounded her as she made the familiar walk, clutching a purse in one hand and an umbrella in the other.

As she approached the cemetery gate, she heard someone behind her. Before she could turn around, something was around her throat and she was being strangled. Taylor struggled against her attacker, trying to break free while being dragged ten feet along the fence that marked the boundary of the marble yard. The attacker picked her up and threw her over the fence. When she hit the ground, the strap around her neck loosened. She screamed for help.

The attacker said that if she screamed anymore, he would cut her throat. Then he resumed choking her.

According to Taylor, she awoke on the ground several minutes later, disoriented and puzzled as to why her clothes were torn and dirty. She then stumbled to her house and told her brother and father what had happened. The Taylor men scoured the cemetery looking for the culprit, only to come up empty. An examination by the family doctor confirmed that she had been raped. Along with redness around her neck, there were bruises on her arms and legs.

Taylor’s father called Hamilton County Sheriff Joseph F. Shipp, who arrived with a search party and bloodhounds. Shipp personally questioned the traumatized Taylor, asking her what she could recall.

She remembered the footsteps. She remembered that her attacker wore a black slouch hat and coat. She thought he might be a little taller than her, which made him over five feet six inches.

Shipp pushed her. What did he look like? Was he white or black?

Taylor said she wasn’t certain—she never saw her attacker’s face—but she believed that he was black with a soft voice.

“Miss Taylor had no opportunity to gain a lucid description of the fiend who assailed her,” the Chattanooga Times reported the very next day, calling the assault “the worst crime ever committed in the vicinity of Chattanooga.”

In retrospect, however, we can say that an even worse crime was about to take place, one that epitomized the era’s lust for mob justice and foreshadowed many issues that became prominent during the civil rights era. Due process, racial equality before the law, federal support for the civil rights of African Americans, all of these fundamental concerns can be seen in the events that followed.

Suspect Apprehension

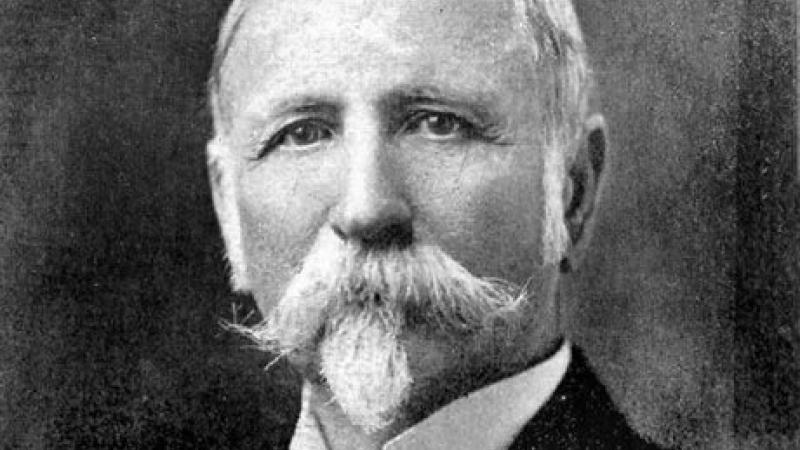

Shipp was near the end of his two-year term as sheriff of Hamilton County. The sixty-year-old businessman had only recently ventured into Democratic politics, aided by a Confederate pedigree and considerable personal wealth. During the Civil War, he had enlisted as a private, rose to the rank of captain, and was wounded three times; afterward, he made a handsome living in the furniture business. If he wanted to remain sheriff—the primary election was fast approaching—he needed to find Taylor’s assailant. The young woman’s description, however, was close to useless. Deputies turned up a strip of black leather that might have been used in the crime, but there was no way to be certain.

Shipp quickly offered a reward of $50 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the rapist. The amount soon swelled to $375 as businesses, the community, and Tennessee’s governor, John Cox, added to the pot. Only two days after the attack, Shipp received a tip from Will Hixson, a twenty-two-year-old man who worked for the Chattanooga Medicine Company. Hixson claimed to have seen, around 6:00 p.m. on September 23rd, a man twirling a strip of leather while standing by the St. Elmo trolley station. When the streetcar with its lights came by, he got a good look at the man’s face. Hixson recognized the man as Ed Johnson.

From the time he was taken into custody, Johnson proclaimed his innocence. Even as Shipp put him through an intense three-hour interrogation, Johnson never wavered from his story: He was across town at the Last Chance Saloon, where at least a dozen people could vouch for his presence.

Johnson had only a fourth-grade education and earned a meager living doing manual labor. He lived with his parents in the black section of Chattanooga known as Higley Row. He often picked up extra money by helping out at the Last Chance Saloon, where he might earn one dollar a night for his work. On the day of Taylor’s assault, Johnson was at the bar, the cold and rainy weather making it impossible to work his construction job. He also denied owning a leather strap. “I didn’t even have any belt, only these suspenders I got on,” he told a newspaper reporter.

News of Johnson’s arrest spread almost instantly. By 7:30 p.m., more than a thousand people, some of them armed, had gathered outside the Hamilton County Jail, shouting “hang ‘em” and “burn ‘em.” Inside, three sheriff’s deputies prepared to defend the jail, with one telling the crowd that they wouldn’t get inside except over his dead body. Impromptu speeches riled up the mob, as bricks shattered the jailhouse windows and guns fired into the air. Members of the mob figured out how to cut off power to the jail, casting the deputies and inmates into darkness. Using a steel beam as a battering ram, men charged at the front door. The National Guard arrived shortly before 9 p.m., but the young and inexperienced soldiers were no match for the crowd.

Around 9:45, with the front door to the jail barely holding, Judge Samuel McReynolds arrived on the scene. He told the crowd to go home, to let the courts do their job. When the mob refused, he asked them who they wanted. The mob shouted for Johnson.

But Johnson wasn’t there.

McReynolds told the crowd that he had ordered Johnson moved to Knoxville. The mob didn’t believe him. They thought it was a trick. To calm things down, McReynolds offered to let a few members of the mob inspect the jail. When the mob’s delegates delivered the news that Johnson wasn’t there, the disappointed crowd went home.

But Ed Johnson wasn’t in Knoxville. He was in Nashville—and he would stay there until his trial began.

Assembling the Defense

Tennessee law mandated a court-appointed attorney for anyone facing the death penalty. Johnson couldn’t afford a lawyer, so it fell to Judge McReynolds to appoint counsel. He chose three men from Chattanooga’s legal community: Robert T. Cameron, a lawyer with minimal trial experience; W.G.M. Thomas, an attorney who specialized in defending companies from lawsuits; and Lewis Shepherd, a former prosecutor and judge who now practiced as a criminal defense lawyer. All three were white. All three would be working pro bono.

McReynolds, the ambitious thirty-three-year-old scion of an old Tennessee family, had secured an appointment as the judge of the criminal court for the sixth circuit of Tennessee through political patronage. Like Shipp, he understood that delivering a guilty verdict would aid his reelection, while a not-guilty verdict would become a permanent blot on his record. McReynolds made it clear to the defense team that the trial would start as soon as possible. He would reject any motions to delay its start or request a change of venue.

Over the next week, Johnson’s defense team scrambled to survey the crime scene, find potential alibis, and meet and interview their client, a task made difficult by his being held more than one hundred thirty miles away. Since Shepherd was simultaneously defending a murder case before McReynolds, the burden of gathering facts fell to Cameron and Thomas. They barely slept, with Thomas claiming not to have removed his shoes for forty-eight hours. They had to deal with backlash from their families, colleagues, and others who were shocked that they were defending a black man accused of raping a white woman. Both men took to Chattanooga’s newspapers to plead for understanding. “[T]his lot has fallen on me, and I shall not dodge or shirk the hard duty imposed,” wrote Thomas. “I am trying to ascertain the truth. I am not trying, and I shall never try, to free a guilty man.”

Before Johnson’s lawyers could meet their client, an enterprising columnist from the Nashville Banner managed to score an interview. “He does not appear to be a Negro of education, is respectful in manner and has not a mean face. If he is faking his story, he is more intelligent than he looks and has rehearsed it until he had it down pretty well.” The interview was also printed in the Chattanooga Times, giving Johnson a chance to proclaim his innocence to the city that had tried to lynch him only days before.

Trial Mismanagement

Johnson’s trial began at 9:00 a.m. on Tuesday, February 6, at the Hamilton County Courthouse. Only nine days had passed since Thomas, Cameron, and Shepherd were appointed defense counsel. Before jury selection began, Johnson’s attorneys asked to have it entered into the record that Judge McReynolds had informed them that any attempt to request a change of venue or a delay would be denied. “As appointees for a man arrested for the worst crime known to men, whose life is involved in the issue—in the face of law and in the interest of justice, we do not believe we have had sufficient time to develop facts to our satisfaction,” said Thomas. But McReynolds would not change his mind. He responded that he believed the trial should take place as soon as possible and in Chattanooga.

A jury of twelve white men was selected from a jury pool of thirty-six white men. No African Americans received a summons to appear. The names of the jury were printed in the newspaper the following day. All of Chattanooga knew the identities of the men deciding Johnson’s fate.

When District Attorney Matt Whitaker called as his first witness Nevada Taylor, a hush fell over the courtroom. Taylor recounted the walk, hearing someone behind her, and what happened next as she was choked and tossed into the marble yard. Then she stated that she had seen her attacker. A faint light, she claimed, given off by the Rapid Transit Company’s block signal allowed her to see her attacker’s face and what he was wearing. Whitaker asked if the man who attacked her was present in the courtroom. She pointed to Ed Johnson, saying that she believed “he was the man.” On cross-examination, Taylor once again said she believed Johnson was her attacker.

The next witness was Taylor’s doctor, who attested to her injuries and the possibility that the strap found at the scene matched her bruising.

Then Will Hixson took the stand, describing for Whitaker how he had seen Johnson at Cemetery Station. During cross- examination, Cameron attacked Hixson’s story right and left. He questioned his desire for the reward. He questioned Hixson, who was white, about a conversation he had had with Harvey McConnell, a well-regarded African American who oversaw work at a church where Johnson once worked. Hixson had boasted to McConnell that he would get the reward, but now denied ever talking to McConnell.

Shipp testified next. He spoke about finding the strap and said that Johnson had changed his story about when he had arrived at the Last Chance Saloon. The sheriff had brought Taylor to Nashville to identify Johnson. During that visit, the sheriff said, Johnson had tried to change the pitch of his voice. Under questioning from Shepherd, the sheriff grudgingly acknowledged that Johnson had never wavered from his claim of innocence and that Taylor had hedged on her identification of Johnson.

Two deputies testified to back up the sheriff’s claim that Johnson had changed his story, then the prosecution rested.

As the trial continued into the early evening, the defense called its first witness: Ed Johnson. “He sat in the witness chair and grasped the arms of the chair with his hands, looking straight at his questioner and leaning far toward him as he answered the questions,” reported the Chattanooga News. As Shepherd asked Johnson a series of questions about himself and his movements on the day of the assault, the crowd in the courtroom heckled and hissed. Judge McReynolds, however, did not admonish the gallery.

Johnson swore that he had never laid eyes on Taylor before his arrest. He also insisted he was at the Last Chance Saloon during the time of the assault, leaving only to fetch firewood at the owner’s request. He also gave the names of nine men who could vouch for his presence. Shepherd asked him if he assaulted Taylor. “No sir,” said Johnson. “I never done what they charged me with. If there’s a God in heaven, I’m innocent.”

Shepherd then called five men who had been at the Last Chance Saloon during the time of the assault to verify that Johnson had been there. Whitaker did his best to shake their stories, but they all stood firm.

On the second day of the trial, Johnson’s lawyers continued to shore up the defendant’s alibi and sow doubt about Hixson’s testimony. They also called a ticket agent and conductor for the Lookout Mountain Incline and Railway, both of whom testified as to how dark it was that night.

On the morning of the third day, the prosecution tried to show that Johnson could have slipped out of the Last Chance Saloon, taken the trolley to St. Elmo, and returned without anyone noticing. The defense poked a hole in that theory by demonstrating that Johnson would have needed to be gone an hour, owing to the train schedule.

During the testimony given by the men who were at the Last Chance Saloon, confusion arose as to whether the clock in the bar worked. To put the issue to rest, Shepherd recalled W. J. Jones, the saloon’s owner, to confirm that the clock on the wall worked, making it possible for people to accurately gauge when they and Johnson had been at the bar.

The jury had to decide whether to believe a white man with questionable motivations or an uneducated black man and the clientele of the Last Chance Saloon.

“I cannot stand it any longer. I cannot stand it,” a member of the jury cried out, tears streaming down his face. McReynolds called for a short recess.

When the jury returned, they bore a request: They wanted Taylor to take the stand again. Half an hour later Taylor was back in court. Then the jury made another request: They wanted Johnson to put on a black slouch hat. Shepherd objected, but McReynolds allowed the request to go forward.

The jury continued to direct the trial. Two jurors pleaded with Taylor to provide a definite statement as to whether Johnson was the man who had assaulted her. She hedged again, saying she believed Johnson was the man. Another juror pressed her to say for certain that it was really him. Taylor raised her hand toward heaven and said, “before God, I believe that is the guilty Negro.”

Jurors began to sob in their chairs, while another stood up and made a move toward Johnson. “If I could get at him, I would tear his heart out right now!” he cried.

McReynolds called for a lunch recess. Afterward, closing arguments began, with each side getting an hour and forty-five minutes to make their case. Around 5:30 p.m., McReynolds handed the case to the jury.

The jury deliberated until midnight, stopping only for dinner. Before they left for home, the foreman reported they were deadlocked: eight votes for guilty and four votes for innocent. They convened again the next morning at 8:00 a.m. A little more than an hour later, they had reached a verdict.

“On the single count of rape, we, the jury, find the defendant, Ed Johnson, guilty.”

The Ticking Clock

Johnson’s lawyers debated whether they ought to pursue an appeal. Shepherd was in favor, but Thomas and Cameron feared that the mob might rise up again if Johnson’s execution was delayed. To break the deadlock, Thomas asked Judge McReynolds to appoint an advisory panel of three additional lawyers. The new lawyers believed there were no obvious grounds for appeal.

When the defense team spoke with Johnson about not appealing his case, Thomas went so far as to tell him he had a choice: He could die at the end of a rope or at the hands of a lynch mob. After Johnson agreed to waive his right to appeal, McReynolds set his execution for March 13, 1906.

Hours after the sentencing, according to Contempt of Court, a history of the case by Mark Curriden and Leroy Phillips Jr., Johnson's father paid a call on Noah Parden, the leading African-American attorney in Chattanooga. Parden and Shepherd had traded notes throughout the case, with Parden helping the defense locate witnesses for Johnson’s alibi. Parden, however, declined an invitation to join the defense, wanting to stay out of the fray. Johnson’s father begged him to make one last attempt to save his son from the gallows.

At the urging of his law partner, Styles L. Hutchins, Parden agreed to take the case. On Tuesday, February 13, Parden and Hutchins filed a motion seeking a new trial. McReynolds rejected the appeal, noting that the motion had not been filed within seventy-two hours, as required. McReynolds counted Sunday as part of the required seventy-two hours, even though that wasn’t the custom. Parden and Hutchins turned to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which denied the appeal and the request for a stay of execution.

On March 7, with the clock ticking on Johnson’s life, Parden and Hutchins tried their luck with the U.S. District Court in Knoxville. The petition invoked the Habeas Corpus Act of 1867, which gave an individual the right to ask a federal court to review their case if they felt their Constitutional rights had been violated by a state court. The law had been put in place during Reconstruction to ensure that African Americans and those who supported the Union would be able to receive due process in former Confederate states. While Johnson’s lawyers could cite numerous problems with the trial—no pre-trial motions, refusal to consider a change of venue, self-incrimination, the right to appeal—the wedge issue was Johnson’s failure to be tried by a jury of his peers. No African Americans had even been in the jury pool, let alone on the jury. They also highlighted Judge McReynolds’s refusal to reprimand the juror for threatening Johnson and his decision to bar Johnson’s parents from attending court.

Their gamble paid off when Judge C. D. Clark granted them a hearing on March 10. For eight hours, Johnson’s attorneys, who once again included Shepherd, traded questions, barbs, and accusations with Whitaker and McReynolds, who resented having their conduct scrutinized. McReynolds denied having told them he would forbid a change of venue or any delay in the trial. He denied barring Johnson’s parents from the courtroom. “At that time I did not know Johnson had any father and mother,” he said. After deliberating for three hours, Clark issued a ten-day stay of execution shortly before 1:00 a.m. in the morning on March 11.

Questions, however, began to be asked about whether Clark, a federal judge, had the authority to delay an execution ordered by the state. To settle the issue, Tennessee governor John Cox agreed to issue a stay on March 12, but there was a catch: It was only for seven days. Johnson’s lawyers had one week to file their appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court.

Because neither Parden nor Hutchins had standing to present a case before the Supreme Court—and there was no time to file an application for admission to the bar—they asked Emanuel D. Hewlett, an African-American attorney based in Washington, D.C., who specialized in criminal law, for assistance. A graduate of Boston University School of Law, Hewlett had previously served as co-counsel on a Supreme Court case.

With four days left on the clock, Parden and Hewlett filed a brief with the clerk of the Supreme Court on March 16. They were asked to return the following day in case Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan, who heard emergency appeals from the 6th Circuit, had any questions for them. Harlan was a lucky draw. The son of a Kentucky slave owner, he had become an advocate for the civil rights of African Americans. Harlan had written the lone—and blistering—dissent from the “separate but equal” ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896.

“Harlan is the justice most keen on enforcing the Fourteenth Amendment as it relates to the rights of African Americans. The case is almost tailor-made for him,” says Brad Snyder, associate professor of law at the University of Wisconsin Law School. When Parden and Hewlett finally received their ten-minute audience with Harlan, the justice peppered them with questions about Johnson’s trial.

On Sunday, March 18, Harlan arranged for telegrams to be sent: One was delivered to the U.S. District Court in Knoxville and one to Shipp. He decided to stay Johnson’s execution, allowing his lawyers to file a petition with the Supreme Court. The telegrams were printed in the newspaper for the entire city to read. “The gallows in the Hamilton County jail has again been disappointed in the case of Ed Johnson, convicted by the state courts of rape, and sentenced to death,” wrote the Chattanooga News.

Parden and Hutchins had obtained the impossible, but the chances of saving Johnson from the hangman’s rope remained slight. “The Court had never interfered in a state criminal trial up to that point,” says Snyder. “It was a long shot for the Supreme Court to take the case. And an even longer shot that they would grant the defendant in the case relief.”

Mob Justice

Shortly after eight o’clock in the evening on the day after Harlan’s telegram arrived, a dozen men entered the Hamilton County Jail. They marched unopposed through the sheriff’s offices, through an unlocked iron door that led to the second floor, and up a flight of stairs. There they found only one deputy on duty, seventy-two-year-old Jeremiah Gibson, whom they easily overpowered. To get Johnson, they now had to unlock the door to the corridor housing the jail cells. After they damaged the lock, the men used a sledgehammer and an axe to break down the door. For three hours they banged away as a crowd outside grew to about a hundred people.

Shipp arrived on the scene, having been alerted by a newspaper reporter to the mayhem at the jail. Men seized him and carried him upstairs, hoping he could produce the needed key. After Shipp refused, he allowed himself

to be shut in the bathroom.

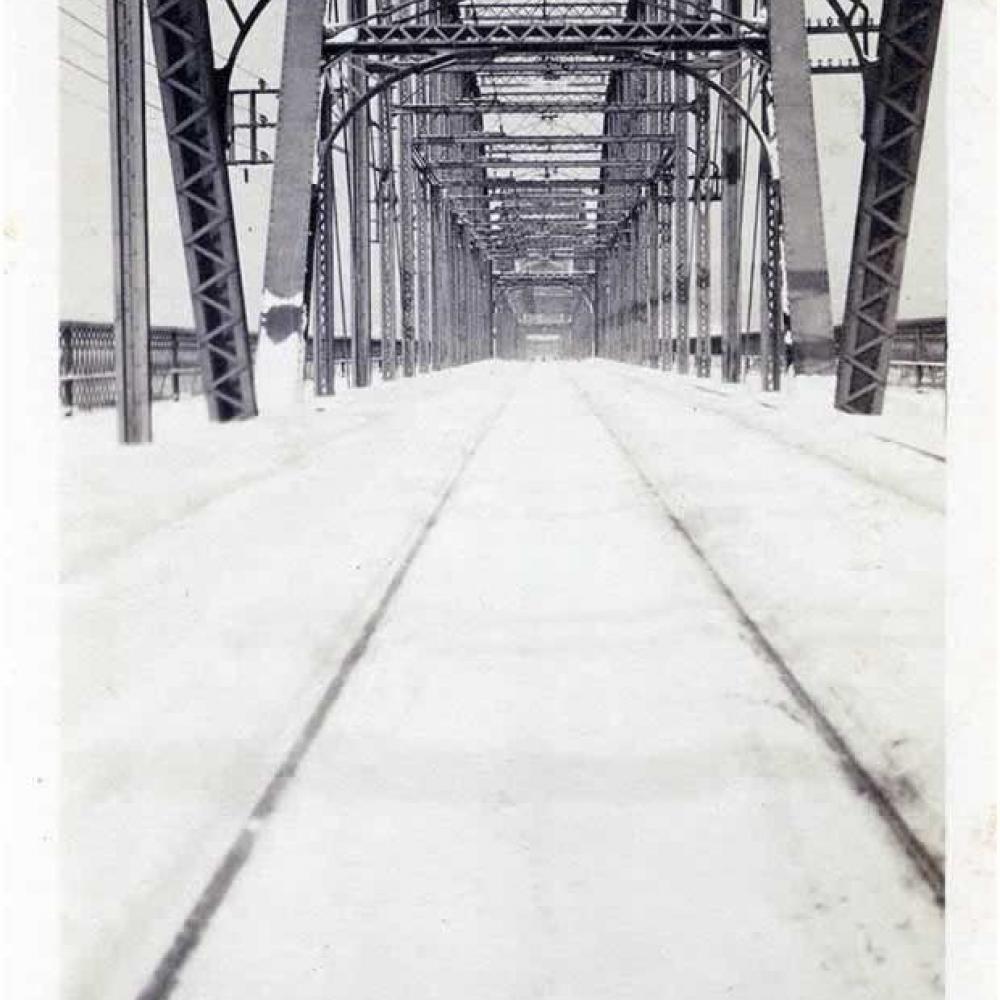

When the door to the jail cell corridor finally gave way around eleven o’clock, the men seized Johnson, tied his hands behind his back, and carted him to the bridge that spanned the Tennessee River. The mob slipped a noose around Johnson’s neck and demanded that he confess. Instead he reasserted his innocence. “I’m ready to die, but I never done it.”

Before the noose tightened, Johnson uttered his final words: “God bless you all. I am innocent.”

The first attempt to hoist Johnson failed, sending his body tumbling to the ground. On the second attempt, the rope held. When Johnson appeared to still have life after a few minutes, the mob riddled his body with bullets. One bullet sliced the rope, sending Johnson plummeting to the ground again. When someone noticed he was still alive, a deputy sheriff stepped forward and shot Johnson five times at point blank range.

Defying Supreme Authority

Johnson’s lynching made the front page of the Washington Post. There were also stories in the New York Times and the Atlanta Journal Constitution, turning Johnson’s death into a national issue.

The disrespect shown for its authority stunned the Supreme Court. “Johnson was tried by little better than mob law before the State court,” said one of the justices off the record. Whether guilty or innocent, the judge added, “he had the right to a fair trial, and the mandate of the Supreme Court has for the first time in the history of the country been openly defied by a community.”

With the court in recess, the justices gathered at Chief Justice Melville Fuller’s house. The one thing they agreed upon was that they could charge the men who lynched Johnson with contempt of court. At the direction of Attorney General William Moody, two Secret Service agents were sent to Chattanooga to gather evidence about the night of March 19.

On May 28, Moody asked the Supreme Court’s permission to require that twenty-five citizens of Chattanooga, including Shipp, be made to answer charges for “contempt of the solemn mandate of the court.” The Secret Service investigation had uncovered ample evidence, Moody argued, that Shipp and his deputies had aided and abetted the lynch mob. The Court agreed.

When a reporter tracked Shipp down for a comment, he said, “The Supreme Court of the United States was responsible for this lynching. I had given that negro every protection that I could. For fourteen days, I had guarded and protected him myself. In my opinion, that act of the Supreme Court of the United States in not allowing the case to remain in our courts was the most unfortunate thing in the history of Tennessee. The people of Hamilton County were willing to let the law take its course until it became known that the case would probably not be disposed of for four or five years by the Supreme Court of the United States. The people would not submit to this, and I do not wonder at it.”

It was very unlikely that the Supreme Court would have agreed to hear Johnson’s case. Had the mob not decided to mete out its own misguided justice, Johnson’s execution would have proceeded in the fall of 1906.

A Question of Jurisdiction

On October 15, 1906, Shipp and twenty-four citizens of Chattanooga filed into the stately Old Senate Chamber at the U.S. Capitol. The Supreme Court had been meeting in the amphitheater-style two-story room since 1860, when the Senate vacated it for a new expanded chamber. All twenty-five defendants entered “not guilty” pleas.

Their defense lawyers raised a variety of issues, including whether the Supreme Court had exceeded its jurisdiction when it granted Johnson’s stay of execution and whether the telegram sent by Harlan was the proper way to give notice. Shipp’s lawyer also questioned whether the Supreme Court had jurisdiction to hear the case.

On Christmas Eve, the Supreme Court issued a decision stating that it had jurisdiction over the lynching case. But the court was not set up to conduct criminal trials. It was set up to hear oral arguments and review briefs. So, the justices agreed to send James D. Maher, the deputy clerk of the Supreme Court, to Chattanooga to conduct the trial there; afterward, the Supreme Court would review the evidence gathered.

The trial opened on February 12, 1907. John Stonecipher, a key prosecution witness, testified as to how the lynchers attempted to recruit him to join the mob, promising that Shipp would not interfere. Stonecipher had moved to Georgia after being told his house would be blown up if he didn’t leave town. Ellen Parker, a moonshiner being held at the county jail at the time of Johnson’s lynching, recounted how Deputy Gibson warned her about the lynching and told her to stay in her cell.

During the recess, word came that Nevada Taylor had died on May 12 of “nervous trouble brought about by the crime.” Any chance of her recanting was now gone forever.

The trial resumed on June 10, with the defense presenting its case. Pastors, neighbors, family members, and colleagues testified for the accused about their character and their whereabouts on the night of the lynching. Shipp testified last, recounting how he had rushed to the jail when he heard about the lynching, only to be imprisoned by the mob. He said he didn’t recognize any of the men involved. He also did not use physical force or draw his gun against the men.

It took the Supreme Court almost two years to sift through the thousands of pages of testimony generated by the trial. On May 24, 1909, the Court issued a ruling written by Fuller and joined by Harlan, Holmes, William Day, and David Brewer. (Moody, who had been elevated to the Court, abstained.) “The assertions that mob violence was not expected and that there was no occasion for providing more than the usual guard of one man for the jail in Chattanooga are quite unreasonable and inconsistent with the statements made by Sheriff Shipp and his deputies that they were looking for a mob on the next day,” wrote Fuller. The chief justice also quoted from the interview Shipp gave, in which Shipp blamed Supreme Court interference for the lynching. Three justices—Rufus Peckham, Edward White, and Joseph McKenna—dissented, arguing that they did not see evidence of a conspiracy. From the initial group of twenty-five, the Supreme Court narrowed its focus to six men: Shipp, Gibson, Luther Williams, Nick Nolan, Henry Padgett, and William Mayse.

On November 15, standing before the justices, Shipp, Williams, and Nolan were sentenced to ninety days in prison. Gibson, Padgett, and Mayse were each sentenced to sixty days. Padgett broke down, covering his face with his hands as he fought back tears. The other five remained stoic.

The prisoners were delivered to the D.C. jail, a squat red brick building at the farthest reaches of Capitol Hill on the bluffs overlooking the Anacostia River. Upon meeting Warden McKee, Shipp noticed a Grand Army of the Republic button on his lapel. “At least we are in the hands of a soldier,” said Shipp. He then turned to his compatriots and declared, “Boys, it will be all right.” It was more than all right. Instead of the standard cell with bars on the door, the men quartered in a large room on the fourth floor, away from the general population. They each had a bed and use of an adjoining bathroom.

Saturday, January 29, 1910, at 8:07 a.m., the door to the D.C. jail swung open, and Shipp, Nolan, and Williams, the remaining three prisoners, stepped into the brisk winter morning two weeks early. To guard against the cold, Shipp wore a threadbare gray Confederate military cape over his shoulders. When their train pulled into Chattanooga the next day, the foot-tapping strains of “I Wish I Was in Dixie” filled the platform. Ten thousand people turned out to welcome them home.

United States v. Shipp stands out in the history of the Supreme Court as an anomaly. It remains the only time the Court has conducted a criminal trial. It hasn’t become part of the civil rights canon, but the case informed the justices’ experiences and future thinking about civil rights issues. “I think it’s a really important data point about the Court’s experiences with Southern justice—and Southern injustice—and trying to provide a fair trial for blacks in the South in the early part of the twentieth century,” says law professor Snyder.

Despite their experience with the Chattanooga lynching, the Supreme Court remained reluctant to interfere in the state courts. Just a few years later, in 1915, it voted against overturning the conviction of Leo Frank, a Jewish man accused of strangling a thirteen-year-old girl in Atlanta, Georgia, despite numerous due process violations during the trial. In their famous dissent, Holmes and Charles Evans Hughes argued, “mob law does not become due process of law by securing the assent of a terrorized jury.” Had he still been alive, Harlan might have signed on as well. After the appeals had been exhausted, the governor of Georgia commuted Frank’s death sentence to life in prison. Angry at the reversal, a mob from Marietta, the girl’s hometown, kidnapped Frank from prison and lynched him.

*This article was updated on December 5, 2014, to reflect that the source for a meeting between Ed Johnson’s father and the lawyer Noah Parden was Contempt of Court: The Turn-of-the-Century Lynching That Launched a Hundred Years of Federalism by Mark Curriden and Leroy Phillips Jr.