“It was in the late twenties that I went to live and work in Paris, and I was then still a French citizen (through my marriage). These two facts would seem to disqualify me as a member of the lost generation or as an expatriate. But I was there, in whatever guise, and even if a bit late.” So begins Kay Boyle’s memoirs of that decade, Being Geniuses Together.

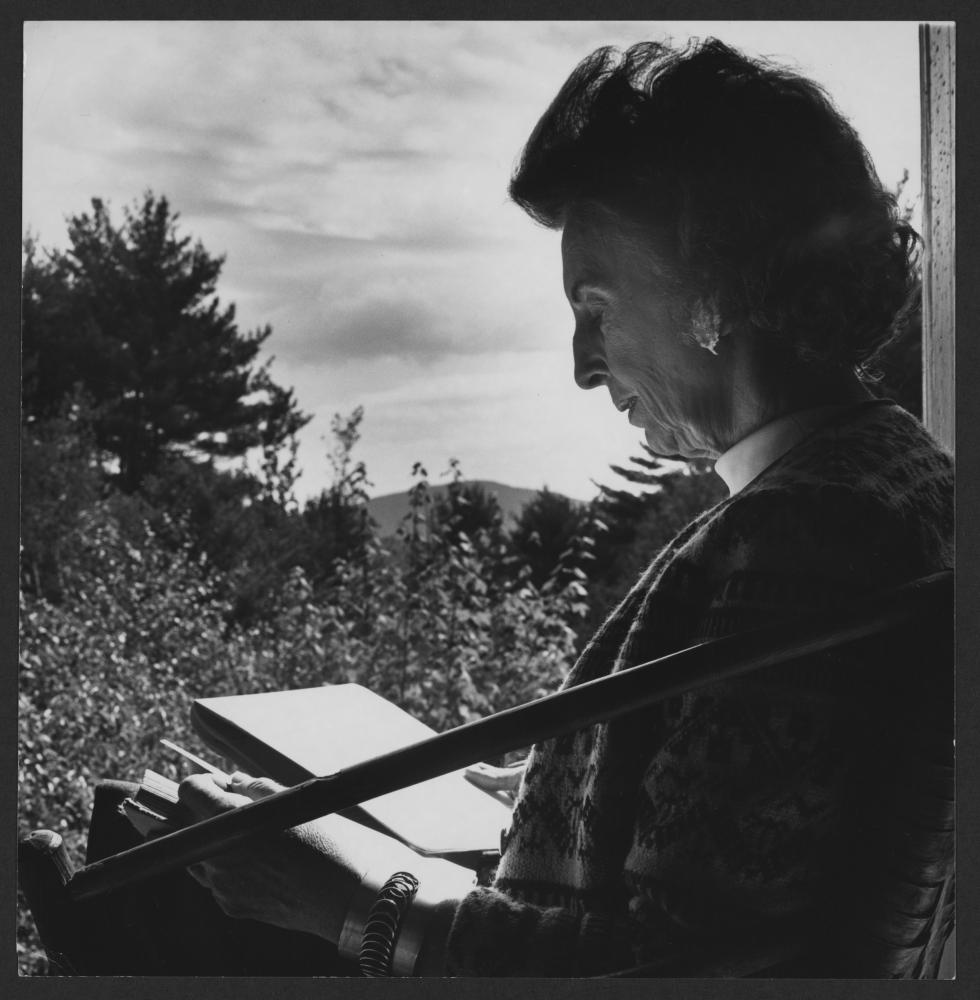

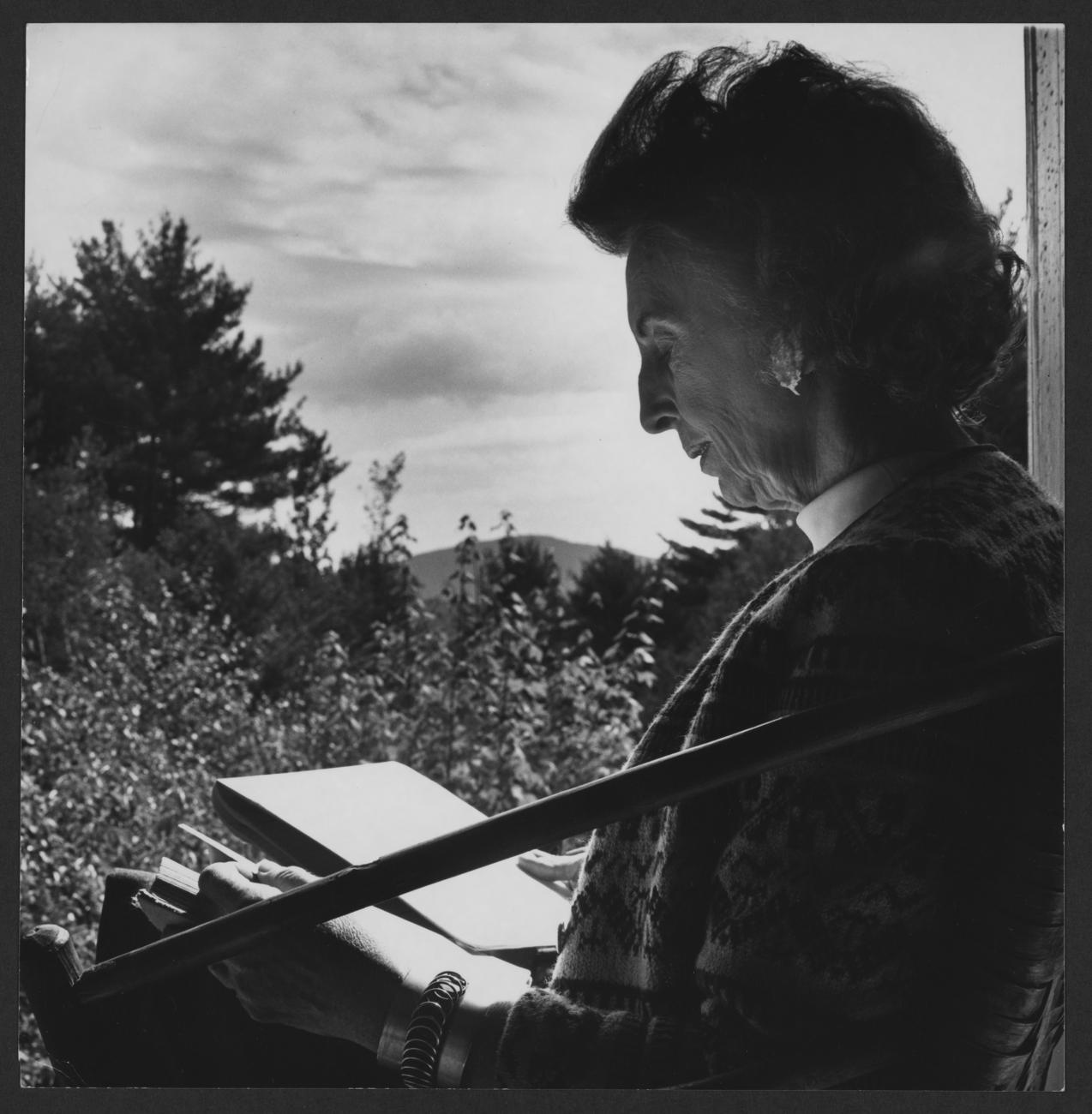

Writer Kay Boyle (1902–1992) had little patience with the legend of the “Lost Generation” of American expatriate artists and writers who gathered in Paris in the 1920s. “I think all this glorification of that wonderful Camelot period is absurd,” Boyle declared in a 1984 New York Times Book Review interview headlined “Paris Wasn’t Like That.”

“I never understood what the Lost Generation meant,” Boyle told NBC television correspondent Pat Mitchell in a 1988 interview for the Today Show. “It was not a community thing at all. It’s been misrepresented. . . . It was characterized by real desperation, there were suicides. And if you sat down at a table at night with some people you knew were writers, if you would mention anything you were doing, everyone would get up and leave the table. You didn’t talk about your work.”

Yet even if she debunked the myth, Boyle most certainly was there. Her early poems and short stories appeared in the avant-garde “little magazines” published in Paris, alongside the works of Ezra Pound, James Joyce, William Carlos Williams, Gertrude Stein, and Ernest Hemingway. Nor did she deny that something momentous was taking place in Paris: “Our daily revolt was against literary pretentiousness, against weary, dreary rhetoric, against out-worn literary conventions. We called our protest ‘the revolution of the word,’ and there is no doubt that it was high time such a revolution took place. . . . There was then, before the Twenties, no lively, wholly American, grandly experimental, and furiously disrespectful school of writing so we had to invent that school,” she wrote in a 1971 essay called “Writers in Metaphysical Revolt.” In 1929, Boyle had been among a group of expatriate writers and artists who signed a manifesto published in transition magazine calling for the “Revolution of the Word” and declaring, “THE WRITER EXPRESSES. HE DOES NOT COMMUNICATE” and “THE PLAIN READER BE DAMNED.”

In a 1931 New Republic review of two of Boyle’s earliest books, Wedding Day and Other Stories (1930) and her first published novel, Plagued by the Nightingale (1931), Katherine Anne Porter declared, “Gertrude Stein and James Joyce were and are the glories of their time and some very portentous talents have emerged from their shadows. Miss Boyle, one of the newest, I believe to be among the strongest.” Identifying Boyle as “part of the most important literary movement of her time,” Porter wrote, “She sums up the salient qualities of that movement: a fighting spirit, freshness of feeling, curiosity, the courage of her own attitude and idiom, a violently dedicated search for the meanings and methods of art.”

William Carlos Williams saw Boyle as Emily Dickinson’s successor. Poet and publisher Harry Crosby, whose Black Sun Press brought out Boyle’s first book, Short Stories, in 1929, called her “the best girl writer since Jane Austen.”

Boyle, who had a knack for always being where the major events of the twentieth century were taking place, had a long and distinguished career. She wrote more than 40 books, among them 14 novels, 11 collections of short fiction, eight volumes of poetry, essay collections, children’s literature, two ghost-written books, and translations of French novels. Her impeccable literary credentials include two O. Henry Awards for Best Short Story of the Year, two Guggenheim fellowships, and membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters, where she (literally) occupied the Henry James chair.

I came to know Boyle in the course of writing a doctoral dissertation about her. My adviser at Penn State, Philip Young, one of the earliest and most influential Hemingway scholars, had refused to let me write about Hemingway, saying he had been done to death and that I should find a topic on which I could say something new. Until I went “shopping” on the library shelves looking for inspiration and happened upon a long line of her books, I had never heard of Boyle.

Flipping through Boyle’s books and reading the author bios, I was immediately intrigued and set to reading everything she had written. Three years later, with a degree in hand and aiming to turn the dissertation into a book, I sent a copy to Boyle and asked her permission to quote from the unpublished letters I had read among her papers at the Southern Illinois University library. I expected a yes or no answer. Instead, in a series of letters over the next several months, she responded to my work page by page, paragraph by paragraph, saying she thought my thesis “deeply right,” but not hesitating to let me know when she thought I was off the mark. She was responding in such “excruciating detail,” she said, because she did not intend to go to such trouble again, and she considered the book her authorized biography. Five years later, in 1986, my book Kay Boyle: Artist and Activist became the first full-length study of her life and work to be published.

In the years that followed, we continued to correspond, and I made periodic visits to the Bay Area to see her. I edited a volume of previously uncollected short stories, Life Being the Best and Other Stories, having had to persuade her that her early experimental fiction was, indeed, still of interest. To her, Paris in the twenties was ancient history. She was far more interested in current politics, social justice, and the problems of her neighbors.

Although Boyle was known in her lifetime as a first-rate novelist and short-story writer, her letters to her contemporaries are equally significant for what they reveal about her eventful times. A roster of her correspondents reads like a twentieth-century Who’s Who. They include Williams, Pound, Porter, and Archibald MacLeish, poet and publisher Robert McAlmon, Black Sun Press publishers Harry and Caresse Crosby, Poetry editor Harriet Monroe, New Directions publisher James Laughlin, New Yorker editor Harold Ross, Richard Wright, William Shirer, Samuel Beckett, Jessica Mitford, and many other famous figures—not to mention scores of family members, friends, politicians, students, and admirers.

Throughout her life, Boyle decried the prurient public interest in writers’ personal lives, but as she approached the age of 90, she seemed to possess a growing sense of her place in literary history and decided that she wanted a collection of her letters to stand as a record of her life in her own words. I was honored when she asked me to take on this project the year before she died. Little did I know that Boyle had written at least 25,000 letters, nor that the project would take more than two decades to complete. I gathered copies of some 7,000 letters from 80 different sources—from 54 libraries and institutional repositories as well from the private collections of more than two dozen individuals, many of whom had known or corresponded with Boyle themselves. From these I selected 378 for a single volume of selected letters, Kay Boyle: A Twentieth-Century Life in Letters.

Of the letters Boyle composed, one she wrote as a brash, young artistic revolutionary was prescient. On August 15, 1930, she wrote to fellow poet Walter Lowenfels: “The present day reader is not worth a ha’penny bit and I don’t care whether his judgments are prejudiced or not. Hell, I’m writing for posterity—I mean, I’m going to. I’m going to write a record of our age and posterity is going to know all about our age and they won’t care if my name is Boyle or Murphy.” In both her published work and her private correspondence, Boyle did, indeed, write “a record of our age.”

Like many of her contemporaries of the so-called “Lost Generation,” Boyle came from the American Midwest. Born in 1902 in St. Paul, Minnesota, she hailed from the same hometown as F. Scott Fitzgerald, who was born there in 1896. But from there her story diverges from the common narrative. When she was two years old, her family left St. Paul, and thanks to the affluence of her grandfather, Jesse Peyton Boyle, an attorney and a cofounder of the West Publishing Company, they “traveled expensively, and dined expansively, in a great many different countries” during her childhood, as she recalled in Being Geniuses Together. They lived in and around Philadelphia and Atlantic City, and summered at a resort in the Poconos.

After the family suffered financial reversals in 1916, Boyle’s father went into the automotive repair business with a cousin in Cincinnati. As that business slowly failed, the family lived in progressively modest dwellings until they finally moved into quarters above the garage in the city’s industrial section. Her mother, Katherine Evans Boyle, was keenly attuned to modern developments in the arts. A friend and correspondent of Alfred Stieglitz, she kept him abreast of her two daughters’ artistic achievements. In 1913, she took Kay and her sister to see the Armory Show in New York City, where Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase was creating a sensation.

Boyle, who had no formal schooling, later wrote that her mother alone had been her education: “Mother accepted me and my word as she accepted James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, or Brancusi, or any serious artist. Because of her, I knew that anyone who wrote, or anyone who painted, or anyone who composed music, had a special place in life. And so, when I got to Paris, and really met these people who were accomplishing things, I felt I belonged with them, because my mother brought me up in that quite simple feeling.”

In 1923, Boyle went to France not to pursue her artistic calling among the Left Bank literati, but because she had married a French exchange student she met in Cincinnati, where he had earned a degree in engineering. At the time, by U.S. law, an American woman had to take her husband’s nationality. When she and her husband, Richard Brault, left to spend the summer with his family in Brittany, Boyle had no way of knowing that she would not return to the United States for 18 years.

She lived her first two years abroad as a French housewife in hardscrabble circumstances, in the port city of Le Havre, then in Harfleur. While her husband put in 12-hour days working for an electric company, Boyle immersed herself in her writing, turning out poems, stories, and “endless letters.” The letters record not only her artistic aims and efforts, what she is reading, and her assessments of other writers, but the mundane struggles of daily life. Writing to her mother (“dearest muddie”) on October 25, 1923, Boyle describes moving into a flat lacking heat, electricity, and running water: “We have had two back-breaking days. Moved in Tuesday in the pouring rain. Cheerfully opened the kitchen shelves and found every dish piled with rotting food—the stove stuffed with all kinds of filth—every sauce pan reeking. For solace I turned to the bedroom—the chamberpot encrusted an inch thick with urine—I had to get it out with a knife.”

In late 1925 Boyle developed a lung condition in the dank northern winter. Gratefully, she accepted an invitation from Ernest Walsh, coeditor with Ethel Moorhead of the little magazine This Quarter, to see his lung specialist in Paris at his expense and then join him and Moorhead for a few months in their rented villa in the South of France to recuperate in the warmth and sun. Boyle soon regained her health, and it was not long before she and Walsh fell in love.

Walsh died of tuberculosis in October 1926 at the age of 31, leaving Boyle pregnant with his child, born in March 1927. Her husband, Richard, invited her and her daughter, Sharon, to return to live with him in Stoke-on-Trent, England, where he had found a job with the Michelin Tire Company. Out of options, Kay accepted. She lasted there a year. “I cannot inflict a platonic wife upon Richard for the rest of his existence, and I want to take care of my daughter myself,” she wrote to poet and editor Lola Ridge on November 29, 1927.

So it was in 1928 that Boyle finally made it to Paris as a single working mother. Largely because she needed housing and child care, she joined the commune of Raymond Duncan (Isadora’s brother), who preached the virtues of the simple life and whose followers wore togas and sandals and subsisted on goat cheese and yogurt. She worked in Duncan’s two Paris gift shops, where goods supposedly handcrafted at the commune (but imported from Greece) were sold to wealthy tourists. Duncan’s hypocrisy revealed itself when he used the proceeds of a large sale to an American museum to buy himself an American luxury automobile instead of a printing press for the colony. With the help of her friends Harry and Caresse Crosby and Robert McAlmon, Boyle was able to “kidnap” her daughter and escape the commune in late 1928. She continued writing, and her circle of friends widened to include leading writers, publishers, and artists of the day, among them Joyce, transition publisher Eugene Jolas, Hart Crane, Emma Goldman, Constantin Brancusi, and Marcel Duchamp (who later would become the godfather of her sixth child, born in 1943).

While the mass of American exiles returned home when the Jazz Age collapsed along with the economy in late 1929, Boyle remained in Europe. That year, on the terrace of La Coupole, she had met Laurence Vail, known as “the King of Bohemia,” and with their melded family they took up a peripatetic life together, following favorable exchange rates across Europe. Their daughter Apple-Joan was born in December 1929, they married in Nice in 1932, their daughter Kathe was born in Kitzbühel, Austria, in 1934, and they frequently cared for Vail’s two children, Sindbad and Pegeen, from his previous marriage to Peggy Guggenheim. Living in Austria in the 1930s, Boyle witnessed firsthand the rise of fascism. She won the 1935 O. Henry Award for Best Short Story of the Year with “The White Horses of Vienna,” which featured a Nazi protagonist. In 1937, they bought a chalet in Megève, a village in the French Alps, dubbing their home “Les Cinq Enfants”—changing the name to “Les Six Enfants” when their third daughter, Clover, was born in 1939.

In letters as well as in her fiction writing, Boyle bore witness to France’s mobilization and the continuities and dissonances of everyday life. “Here half the world is skiing while the other half dies, and the night-clubs are open until three in the morning, and God knows how people can dance as madly as that and as late and be as happy as they are,” she wrote to Caresse Crosby on February 16, 1940, four months before France fell to Nazi Germany.

In the summer of 1941, war finally forced Boyle and her family from Europe. Through months of herculean efforts with various authorities, Boyle managed to arrange passage to America by way of Lisbon via the Pan Am Clipper. The returning entourage included her second husband, Laurence Vail; his ex-wife, Peggy Guggenheim; Guggenheim’s husband-to-be, Max Ernst; and the combined brood of six children. A photograph published in the New York World-Telegram shows the family looking dazed upon disembarking in New York City on July 14, 1941.

What the papers did not report was that Boyle had arranged separate passage on a refugee ship for her husband-to-be, Joseph von Franckenstein, an Austrian baron who had fled Nazism in 1938, whom she had met in Megève, where he was a ski instructor and the children’s tutor. Boyle and Franckenstein would marry in 1943 and have two children: Faith, her fifth daughter, and Ian, her first son.

Back in America, angered by the talk she heard accusing the French of having “lain down on the job,” Boyle began churning out stories for mass-market magazines—both to earn a living and to communicate to the widest possible audience what was happening in Europe. She went on the lecture circuit to speak about France under the German occupation. Her talk consisted of “actual stories of the defeat and of the people’s reaction to occupation, scenes in which I participated myself, an indictment of the State Department, and of the Fascist element in every country,” she wrote Robert McAlmon on December 6, 1941. “The whole thing is an attempt to demonstrate further that nothing is of any importance except the individual resistance and the individual protest.”

Boyle’s 1944 novel, Avalanche, originally serialized in the Saturday Evening Post, was the first novel about the French Resistance—and her only best-seller. In the meantime, Joseph Franckenstein became an American citizen, joined the U.S. Mountain Infantry and later the OSS, the predecessor of the CIA, and engaged in intelligence work behind enemy lines. He infiltrated into Austria in the guise of a German sergeant, worked with resistance groups, and after being captured and tortured by the Gestapo, he narrowly escaped with his life.

After the war, Franckenstein and Boyle returned to Europe, he as a U.S. Foreign Service officer, and she as a foreign correspondent for the New Yorker, assigned by editor Harold Ross to “bring fiction out of Occupied Germany.” In 1952, in the heyday of the McCarthy witch hunt, they were subjected to a loyalty-security hearing in Marburg, Germany. Janet Flanner, the New Yorker’s longtime Paris correspondent, testified eloquently for the defense, and after Boyle put her friend back on the train to Paris, she wrote to her New York agent, Ann Watkins, on October 23, 1952:

Everyone feels confident that the decision of the panel will be the right one, but we will not know what this decision is for several weeks. I shall write you at length about everything very soon, but at the present moment I feel so depressed, so crushed even, by the humiliation, the degradation, the shocking injustice of all this, that I can only feel numbly for some sort of action to take to help keep this kind of thing from happening to other honest people. Joseph has aged ten years—he is haggard—his heart, let us hope, only temporarily, broken—but broken without any doubt.

Boyle and Franckenstein were unanimously cleared of all charges, but within a few months, he and several other government employees who had been cleared by the loyalty-security panel, were dismissed from the Foreign Service “in the interest of national security.” Then the New Yorker withdrew her accreditation. The family was forced to return to the United States, where Franckenstein took a job teaching at a girls’ school in Rowayton, Connecticut, and Boyle found herself blacklisted, unable to place her work for most of the rest of the decade.

For nine years they fought to clear their names, and Franckenstein was finally reinstated, with apologies from the State Department, in 1962. Soon after taking up a post as cultural attaché at the American embassy in Tehran, he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. A few months before his death, Boyle put out word that she was seeking a job. In 1963, she accepted a position on the creative writing faculty at San Francisco State University, where she taught until she retired in 1979.

Living two blocks from the intersection of Haight and Ashbury streets, Boyle was at the epicenter of another cultural revolution. Throughout the sixties and seventies she became a prominent figure in Bay Area protests and picket lines. She got herself publicly fired by university president S. I. Hayakawa during the 1968 student strike and was arrested for blocking access to the Oakland Induction Center at the height of the war in Vietnam, going to jail with Joan Baez and the singer’s mother. She turned her annual birthday parties into fund-raising events for Amnesty International. Well into her eighties, always strapped for money, she took a number of short-term positions teaching creative writing at various universities (customarily opening her courses by admonishing her students never again to take another creative writing course). After moving to a retirement community in Marin County in 1989, she delighted in discomfiting some fellow residents when she determined to integrate the dining room by inviting friends of color to lunch. Until her death in 1992, Boyle continued to speak out in print and in person in support of human rights and social justice.

Boyle’s letters are a portrait of the artist in the continuous present tense. Through them we can chart Boyle’s personal life on an almost daily basis. (She wrote more than 4,000 letters to her husband Joseph von Franckenstein alone. Along with 1,548 of his letters to her, they survive among her papers at the Morris Library at Southern Illinois University, where she had stipulated that their correspondence be sealed for 10 years after her death.) But beyond their biographical interest and their value for illuminating her creative process, Boyle’s letters narrate a running eyewitness history of her times.

My work on Kay Boyle yielded an unexpected reward: the discovery of a carbon typescript of her long-lost first novel, Process, which was written in 1924 and 1925 in France. Boyle had presumed it lost, after she gave her only copy to a potential publisher. The manuscript had been hiding in plain sight—in the Berg Collection of English and American Literature at the New York Public Library. How it got there is a mystery, but the manuscript was among the papers of Boyle’s friend of the 1920s, Louise Theis.

Published for the first time in 2001 by the University of Illinois Press, Process: A Novel combines aesthetic experimentation and social activism. Underpinning it is the view that progressivism in politics and in the arts are “deeply, deeply united.” We can only wonder how the novel would have been received and how Boyle’s literary reputation might have been affected had it been published at the beginning of her career.

In 1986, when she was 84 years old, Boyle’s friend Studs Terkel told an interviewer, “When I think of Kay Boyle, I think of someone who has borne witness to the most traumatic and shattering events of our century: not simply this particular era, but of the whole twentieth century. Starting early. Both as a creative artist as well as being there. . . . All those events that one way or another, for better or for worse have altered all of our lives, Kay Boyle, writer, participant, was there.”

“Why is Kay Boyle not better known?” he asked. “Things are out of joint when someone like Kay Boyle is not as celebrated as she should be.”