The American poet-critic Ezra Pound believed that present throughout history are nodes of energy, bundles of power and expression that meld together many diverse and even conflicting forces and ideas into a harmonious whole. These nodes of energy could be poetic images, Chinese ideograms, coins, buildings, presidential administrations. His name for them changed over time: Sometimes they were “luminous details,” later “images,” then around World War I they became “vortices.” But whatever he called them, they constituted the basic building blocks of his poetics and his criticism.

Even people could fit into this category—he called such individuals “factive personalities.” Confucius was one. So was the Renaissance condottiere Sigismondo Malatesta. So was another Italian, Benito Mussolini. (Pound had a fascism thing.)

Pound was astonishingly perceptive at times, but distressingly blind at others. (See Mussolini, above.) So, it’s not terribly surprising that he never recognized that one of the people closest to him for almost forty years was just such a node of energy. Although Pound never noticed, it’s not too much of a stretch to see James Laughlin—Pound’s admirer, disciple, student, PR agent, publisher, counselor, friend—as a kind of Poundian “factive personality” whose life amalgamated many seemingly dissonant strains in twentieth-century America into a coherent whole, and in doing so changed the direction of U.S. cultural history.

In Laughlin’s life story—which Ian MacNiven thoroughly and entertainingly recounts in his 2014 biography “Literchoor Is My Beat”: A Life of James Laughlin, Publisher of New Directions—we see many of the key developments of the American century. Take, for example, large-scale industrialization and the labor movement: Laughlin came from the Jones & Laughlin steel fortune, and Henry Clay Frick was a great uncle. Or the continuing cultural dominance of the New England and New York elite: Laughlin attended their schools (Choate, Harvard), but was snubbed, no matter how much money or cultural prestige he brought. But the greatest thing Laughlin did was energize the American literary scene through New Directions books and, perhaps more importantly, framed modernist literature as a worldwide phenomenon in which American artists were just as important as experimental French or British writers. At the same time, he published underappreciated authors from places like Burma, Japan, Argentina, and Brazil, ushering writers from outside the Euro-American world into the literary establishment. Laughlin also proudly promoted American culture abroad and was deeply involved in Cold War cultural-diplomatic “public-private partnerships.” He even helped create the modern skiing industry.

All twentieth-century American roads may not have run through Laughlin, but many of them intersected there. Thus, it’s appropriate that he came from Pittsburgh, like Laughlin himself, an underappreciated Poundian “vortex” of twentieth-century United States. The city’s status as a punchline or a byword for pollution and philistinery is fading quickly, but the city in 1914, when Laughlin was born, deserved its reputation. Pollution dwarfing today’s Beijing, poisoned rivers running unspeakable colors, overcrowded row houses for the immigrants from Eastern Europe and, later, the American South: It was aptly called “Hell with the lid off.”

Laughlin knew his hometown hadn’t given him much in the way of refinement. He joked that society families passed around chewing gum on a silver salver after dinner, and once told Pound that “I ought to be writing about the ‘ineffable translucency’ of your metric, or something like that, but hell, I was born in PITTSBURGH.” Nor did his family prepare him for a literary life. His mother, Marjory, was a strict Presbyterian, and, in terms of books, his house had “nothing but sets and the Bible, and the sets were never read.”

He did know from an early age that he had no desire to go into the family business, and described his annual Thanksgiving trip to see the mill as “like the Inferno . . . terrifying.” His father, Henry, shared his feelings, and so the family spent a great deal of time at their farm in Pennsylvania’s Laurel Highlands and at “Sidoney,” their estate in central Florida. (A private railcar shuttled them there.) In 1927, along with his older brother, Hugh, twelve-year-old James was shipped off to Institut Le Rosey, a swanky boarding school on Lake Geneva. The ostensible reason was to give the boys culture and French, but MacNiven points out that at this time Henry had started to exhibit the volatile bipolar disorder that afflicted Laughlin men, and Marjory didn’t want her boys to see it.

While he didn’t perfect his French at Le Rosey, Laughlin did kindle his lifelong love of skiing there. Laughlin’s passion, his wealth, and the burgeoning popularity of the sport were happy companions, catalyzing each other. In 1934, Laughlin competed on the first Harvard varsity ski squad at venues like Woodstock Hill, in Vermont, which had just installed the first rope tow in the United States. (The first chairlift didn’t come until 1936 when it was developed by the Union Pacific Railroad at Idaho’s Sun Valley resort.) With his graduation money, in 1940 Laughlin bought a mountain lodge in Alta, Utah, and installed a state-of-the-art lift there. Alta soon became a training ground for U.S. Army alpine units and developed into one of the best ski resorts in the West. The lift, but not the resort itself, still belongs to the Laughlin family.

A tall man, close to six and a half feet, he often observed that he felt graceful only on skis. He was good, too. In the winter of 1936, he beat an Olympian and the Canadian national champion in a slalom race on Mt. Baker in Washington state. In 1937, he competed as part of the United States Expeditionary Alpine and Nordic Team in New Zealand and Australia—but had to cut that junket short after a bad crash on Mt. Hotham, near Melbourne.

The crash wasn’t the worst outcome of that trip. Although only 22, Laughlin had already embarked on his publishing career, and the first real book published by his brand-new imprint had come out just before he left for the Antipodes. He wasn’t a typical young publisher, and the book wasn’t some parlor versifier’s chapbook, either. William Carlos Williams, one of the leading American experimental poets of the twentieth century, was optimistic that his first foray into short fiction, White Mule, would prove that he could write something beyond poetry, and might even make him some money. When he saw reviews of this book in The Nation, the New York Times, the New Republic, and even the ultra-middlebrow Saturday Review of Literature, prospects looked good. But then the first printing of five hundred copies sold out, and the publisher’s father informed the enraged author that only James, who was unreachable in Australia, could get the unbound sheets out of storage and to the bindery. It would be years before Laughlin’s relationship with Williams healed.

The drama with Williams, though, didn’t compare with Laughlin’s long, fraught, and crucial relationship with Ezra Pound, who was the key figure in Laughlin’s life and career. Armed with an introduction from his Choate master Dudley Fitts, Laughlin had initially requested to “see” the notorious poet Pound while on a summer trip to Europe in 1933. “Visibility high,” Pound gnomically responded. The still-teenaged Laughlin briefly stayed with Pound, then returned for an extended visit the following November (after a time lodging with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas at their farmhouse in the Alps).

Stein had once referred to Ezra Pound as a “village explainer, excellent if you were a village, but if you were not, not.” Pound’s village in 1934 was Rapallo, Italy, where he maintained what he called the “Ezuversity.” Students and acolytes could spend their days with the poet, playing tennis and swimming in the Tigullian Gulf and, as a core curriculum, listening to Pound expound on everything: poetic meter, Chinese bureaucracy, late medieval banking. Laughlin loved it, and stayed for months.

He was less pleased with Pound’s opinion of his own writing. Since prep school, Laughlin had written poetry, influenced by people like T. S. Eliot and Williams and Pound, and asked for the master’s assessment. “You’re never going to be any good as a poet,” he offhandedly told the crushed Laughlin, who secretly yearned for a career as a writer. Do something useful with your money, Pound advised him—go into publishing, so that even if you can’t write good stuff, you can make sure that good stuff gets out there.

That’s just what he did. Returning to Harvard, Laughlin used a little family money and started a publishing venture that he called “New Directions” (or, in Pound’s formulation, “Nude Erections”) out of his Eliot House lodgings. Initially, New Directions was simply an annual anthology (New Directions in Prose and Poetry) with a list of contributors that a 22-year-old shouldn’t have been able to corral: Pound, Stein, Williams, Henry Miller, Elizabeth Bishop, Marianne Moore, and a pseudonymous Laughlin. Within a couple of years, Laughlin was publishing books—Williams’s ill-fated White Mule, but also volumes of poetry by Kay Boyle and Robert McAlmon and Dudley Fitts, and Pound’s idiosyncratic 1938 literary history Culture.

Also among these early New Directions titles was Delmore Schwartz’s story collection In Dreams Begin Responsibilities. Schwartz, an instructor in Harvard’s writing program, worked as Laughlin’s “office assistant” and was just one of the constellation of future literary luminaries in whose orbit Laughlin hovered—or vice versa. Robert Lowell remembered that in stuffy late 1930s Harvard Square James Laughlin was the man to talk to if you had any interest in avant-garde literature. He’d been to Europe; he knew Pound and Stein and Williams. Since his freshman year he’d been attending a Thursday evening supper group with literary critic R. P. Blackmur and the still relatively obscure John Cheever. Laughlin took writing classes overseen by the archconservative Robert Hillyer, but then in the evenings employed Hillyer’s junior faculty Schwartz and John Berryman, themselves at the time aspiring experimental writers. He was connected up and down the Ivy League, working with Lincoln Kirstein on Yale’s Hound and Horn as well as on Harvard’s own Advocate.

Laughlin went into literary publishing, driven by a strong sense of mission, and laid out his almost mystical vision of the power of experimental literature to transform consciousness and society in the manifesto-like preface to the first New Directions anthology in 1936. Of course, 1936 was a bad time all around, and Laughlin’s friendship with Pound only intensified his sense of impending doom. And when the feared, inevitable cataclysm came, in 1939, it did change both the course of his life and of his publishing house. Laughlin didn’t serve; he was declared 4-F for reasons that remain fuzzy (his powerful family might have pulled strings to get him out, or the family curse, which had claimed his father and uncle in the previous few years, might have been the reason), and so he continued to run the press through the war, even though its output was limited by paper rationing.

He also had to quickly learn to follow his own instincts, and not the desires of his authors. In 1939, he obtained the contract for Pound’s ongoing Cantos project, a long and difficult poem being published in installments. Sunk deep in Pound’s Fascist and anti-Semitic period, the volume Laughlin was to publish first (Cantos LII–LXXI) included several passages that Laughlin feared were not only offensive, but libelous. He stood up to his mentor, demanded changes to the text and—without Pound’s knowledge and against his desires—included in this volume an explanatory pamphlet intended to draw readers’ attention away from Pound’s notorious pro-Fascist statements. During the war, of course, Pound would propagandize on Italian state radio. He was indicted for treason, captured, returned to the United States to face trial, and ultimately languished for thirteen years in a federal mental institution before the charges were dropped. After 1945, Laughlin coordinated both his legal defense and the publicity campaign to rehabilitate the disgraced poet.

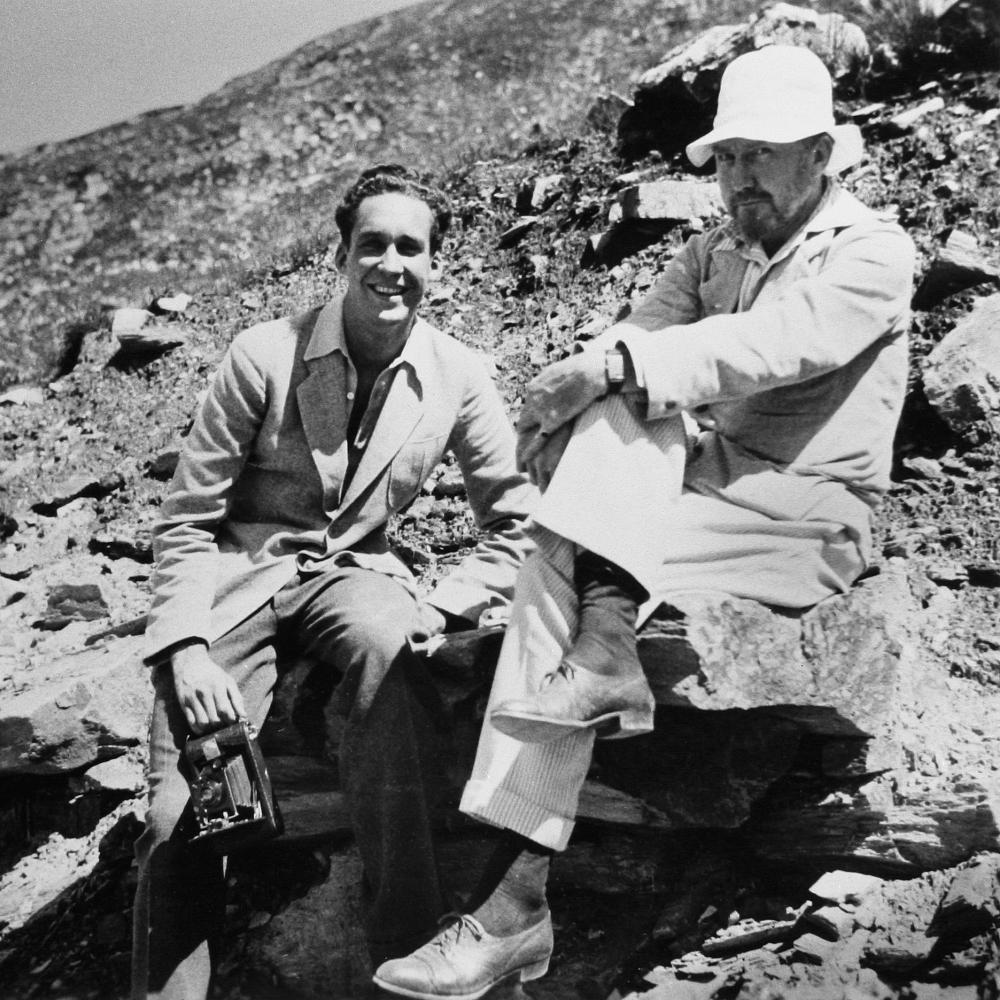

The Cantos LII–LXXI incident showed Laughlin at his most characteristic. He was a romancer, a flatterer; he collected mentors by making them feel important, and he never lost sight of how appealing he was—rich, erudite, cultured—as a disciple. But he never let this cultivation of mentors get in the way of his business. He told Pound no, even though he knew it would enrage the poet. He loved the erratic, shambling Schwartz, and employed him much longer than he really should have, but once Schwartz’s intoxicated antics threatened New Directions, Laughlin unsentimentally cut him loose. Kenneth Rexroth, the San Francisco poet and bohemian who was particularly close to Laughlin—the two went on long skiing and camping expeditions in the Sierras—blustered about the fact that rich Laughlin would never put him on a stipend, but Laughlin refused to consider it. (Instead, he asked other people whether they would front Rexroth some money.)

Laughlin never intended to run a hothouse imprint, a Lost Generation-style futile stab at publishing evanescence. Nor did he see New Directions as the vanity project of a rich dilettante. He always intended, as he told Pound in 1939, to run New Directions as an “efficient business.” (Laughlin was proud that New Directions turned its first profit in 1947 and was in the black more often than not after that.) To that end, he looked to the new generation of literary publishers, most of them Jewish and based in New York, that had supplanted the Boston publishing establishment in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Ben Huebsch, Horace Liveright, and especially Alfred A. Knopf became his models (and Bennett Cerf his putative adversary, although he cribbed more from Cerf than he cared to admit).

New Directions pioneered branding. To this day, its black-and-white trade paperback covers are immediately identifiable. Like Cerf’s Modern Library, Laughlin licensed the copyrights to out-of-print modern works and produced discount versions of them for series like “The New Classics”; in 1945, for instance, he rescued Fitzgerald’s forgotten The Great Gatsby from obscurity. After the G.I. Bill filled campuses to bursting, Laughlin packed up a station wagon with student-priced exam copies of New Directions books and gave them to friendly English professors like Hugh Kenner in the hopes that they’d be adopted for modern literature courses. And once Jason Epstein developed the trade paperback at Anchor Books in 1953, Laughlin pounced, persuading his authors that sales to the vast student market would offset the format’s lower royalty rates. Laughlin was never a hippie, not even close, but few 1960s crash pads lacked New Directions editions of Ezra Pound’s Selected Poems, Rimbaud’s Season in Hell, Thomas Merton’s books on Zen, Jorge Luis Borges’s Labyrinths, or at least Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha.

Of course, Laughlin was right in the middle of every literary development in the U.S. between 1940 and the 1980s. He refused to take part in the corporatization and conglomeratization of American publishing, even as he saw his friend Alfred Knopf and his rival Roger Straus succumb. Laughlin always owned the company outright and its shares passed to an ownership trust on his death in 1997.

Between his involvement in publishing and his family’s wealth and profile, Laughlin’s life story can often seem like an endless Page Six of mid-century notables, panning from Drue Heinz (wife of his childhood pal Jack) to Andy Warhol (who designed book jackets for New Directions in the 1950s) to Henri Matisse (whose granddaughter was Laughlin’s secretary) to Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon (a Pittsburgh neighbor he knew as “Uncle Andy”) to Tennessee Williams, Laughlin’s great friend and rival for the affections of the Russian actress Maria Britneva, later Lady Maria St. Just. (Yes, that Tennessee Williams, the gay one. It was complicated.)

It helped that he was oddly gentle and sensuous for such a large man, thoughtful and attentive to whomever he was talking. He had a charisma that made people want to trust him—and then, of course, he had the money and the taste for living that made people want to hang around him. Predictably, he was also a career philanderer, marrying three times and having countless lovers. (Even prostate surgery didn’t end it.) He radiated confidence, cultural sophistication, and a genuine enthusiasm for new experiences. I interviewed him near the end of his life, a poor graduate student making a pilgrimage to the country estate of a literary great, and his personal qualities cut through my fear and awe and nervousness. I could see why he would have been so often present at significant times and with memorable people.

But he wasn’t some sort of Zelig figure, merely there. Always, he was fulfilling what he saw as his mission in life: renewing and energizing the world through good literature. Laughlin had internalized the noblesse oblige best articulated in his fellow Pittsburgher Andrew Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth,” and added to that a dollop of guilt. As he told an interviewer, “I have a strong family concept of how we have to make up for being in the steel wars. . . . I wanted New Directions to go a little way to redeem the family in their dullness and sordidness, in their search for money.” By the time World War II ended and the Cold War began, Laughlin found himself eager to serve his country as well, in the best way he could: through literature.

During the war, Laughlin had declined an invitation to sign on with the Department of State, although New Directions did publish in 1942 an Anthology of Contemporary Latin-American Poetry that was secretly subsidized by the Office of Inter-American Affairs. The Iron Curtain, and in particular communism’s curtailment of artistic freedom, spurred Laughlin to get involved with American outreach in the early 1950s. He kept the government at arm’s length, though, instead doing his work through a private group: the massively wealthy Ford Foundation.

Ford had come into its money in the late 1940s and had already undertaken some extremely ambitious projects domestically. When former Marshall Plan administrators such as Milton Katz and Paul Hoffman came to the foundation, it began to look for ways to promote “cultural freedom” back in Europe. Wanting to give Europeans a taste of all of the innovative American art and literature they had missed because of the war, Laughlin proposed that Ford fund a magazine to do just that. Fortunately, his old friend Robert Hutchins—the former University of Chicago president and celebrity middlebrow intellectual—had also become a foundation director, and, in 1952, Laughlin brought out the first issue of Perspectives USA in English, French, Italian, and German.

Perspectives wasn’t exactly misbegotten, but nor was it one of the successes of Laughlin’s life. His early plans for a cutting-edge magazine of culture, with rotating guest editors like Lionel Trilling, quickly fizzled. The contents were stale, consisting largely of reprinted material from magazines like the New Yorker or the Atlantic. And much of the literary material—thirty-year-old poems by Williams, for example—was dated. Then Laughlin’s managing editor, the poet Hayden Carruth, was institutionalized after an alcoholic breakdown; and Perspectives’ European translator turned out to be a grifter; and the brand-new Congress for Cultural Freedom brought out its own livelier version of this same idea (Encounter, edited by Irving Kristol and the English poet Stephen Spender); and Ford lost interest and pulled its funding. Perspectives limped through sixteen issues without publishing one notable original piece.

The only article with any impact, in fact, was Mary McCarthy’s “America, the Beautiful,” reprinted from a 1947 issue of Commentary. And it wasn’t readers who responded to it—it was William J. Casey, a member of Perspectives’ board of directors. (Casey had been an OSS spy during the war, and later became President Reagan’s director of central intelligence. Whether he still had his hand in the trade during this time is . . . unclear.) Laughlin’s board was stocked with corporate types like H. J. Heinz and Richard Weil Jr. of Macy’s and James Brownlee of J. H. Whitney, but only Casey reacted with anger to the prospect of printing McCarthy’s equivocal, ambivalent defense of American “plain and heroic accessibility.” Casey, a conservative Long Island Catholic, charged that it was typical New York Intellectual condescension, and demanded that Laughlin print something to balance it out—a piece by Peter Drucker, he suggested.

By then Laughlin himself was losing interest in Perspectives, and he’d used part of the Ford Foundation money to travel in Burma, Japan, and India. The plan was to create an offshoot of Perspectives that would focus on the contemporary art and literature of those nations, but Laughlin was also scouting for potential New Directions authors. He found them, too, and in subsequent years the firm put out titles translated from Sanskrit, Bengali, Hindi, and Burmese, and signed Yukio Mishima as a New Directions author. New Directions had long published books by Western authors influenced by Asian literature such as Thomas Merton and Pound and Hesse and Kenneth Rexroth, but in the late 1950s the firm’s books made Asian writing and ideas much more available to American readers. It’s hard not to conclude that Laughlin was at least partly responsible for fueling the counterculture’s interest in Asian philosophy and spirituality.

And even with all of his other work, he continued to write. He frequently published poetry in the New Directions annuals, often under humorous pseudonyms. One of New Directions’ first books was a collection of his own poetry. He published dozens of collections, most of them not with New Directions, and in the 1980s began dedicating himself almost full-time to his writing. His proudest moment, he said, was being inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1995 as a poet. (In 2014, New Directions released a massive collected edition of Laughlin’s poetry.)

There was a tragic side to his burgeoning success as a poet, though. In 1968, Merton, the Trappist monk and writer who had become a close friend to Laughlin, died in Bangkok, electrocuted by a faulty fan. Laughlin was distraught. Worse, this incident seems to have triggered the family curse in Laughlin. From the late 1960s on, he struggled with what we would now call bipolar disorder. As with so many other developments of the century, Laughlin found himself, against his desires, at the center of the revolutionary changes in mental health treatment and pharmacology. At first, he relied on lithium, which often dulled his ability to write, but the development of SSRIs like Prozac helped. The curse was brutal, relentless, and seemingly inevitable. In 1986, Laughlin’s son Robert slit his wrists in Laughlin’s Greenwich Village apartment, to be found by his father. And, just in August 2014, another of Laughlin’s sons, Henry, committed suicide.

When Laughlin himself died in 1997, most obituaries focused, naturally, on his work with New Directions and his relationships with luminaries such as Pound and Williams and Merton. New Directions was portrayed almost as a curiosity, a holdover from another era of publishing that would certainly fade when its guiding spirit passed. That hasn’t happened. The firm is healthy today and continues to find exciting new authors. And while in some ways the firm is a throwback, in another way its approach to publishing foreshadowed the “curated” aesthetic and long-tail strategy of digital-age publishing. New Directions finds a small number of very good authors, publishes most of what they write in small print runs, and keeps them in print for a long time, realizing that readers will eventually discover them.

In publishing and beyond it, Laughlin helped bury the once-widespread prejudice that “American culture” was an oxymoron. In the 1930s, he brought cutting-edge modernist art and literature to the stuffy Ivy Leagues and then, through his student-aimed books, to a new generation of adventurous readers across the country. After the war, he turned his talents to the project of persuading influential European intellectuals, particularly in France and Great Britain, that American authors had indeed produced literature worth reading, “books of permanent literary value,” as New Directions’ first circular put it. Laughlin was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1953 for bringing French literature to America, but was even more important in nurturing the careers of American writers from Pound to Williams to H. D. to Mary Karr. And he did this because of his belief, perhaps anachronistic but widely shared among cultural notables of the 1950s, that American-style freedom and individualism weren’t anathema to sophisticated experimental art and literature but rather fostered them. At a time when the U.S. political establishment still saw modernist art as a stalking-horse for subversion, Laughlin and others did what they could to obliterate that belief, showing skeptics in Europe and cultural conservatives in the United States that there was nothing more American than sophisticated, challenging, and truly multicultural art and literature