Henry David Thoreau isn’t usually known for flattering comments about women. But after a few hours of conversation with the 77-year-old Mary Moody Emerson, one November evening in 1851, he complimented both her intellect and her youthful spirit. The aunt of his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson, Mary Emerson was in Thoreau’s estimation not only “a genius,” but “the wittiest & most vivacious woman” he knew. A few years later, he amplified these accolades by telling a friend that Emerson, now age 81, was in fact “the youngest person in Concord.” Thoreau and Emerson enjoyed many hours together during her frequent visits there. On more than one occasion she asked to read his writings; and, when leaving town, she requested he correspond with her, so as to “brighten the solitude so desired.” Insightful as ever, Thoreau gleaned an essential feature of Emerson’s personality—a vibrant, open-minded engagement with others. Over the course of a long life, Emerson cultivated intellectual relationships, especially with younger women and men, like Thoreau, whose stimulating company she craved.

Born in 1774, on the eve of the American Revolution, in Concord, Massachusetts, Emerson cherished her connection to that historic town. Meeting her “beloved Fayette” during his triumphal 1824–1825 tour of the United States, the adult Emerson quipped to the influential Marquis de Lafayette that as an infant “in arms” she had witnessed the famous Concord fight that began it all. But, in 1776, when her father, William Emerson (a chaplain to the Continental Army at Fort Ticonderoga), died, his widow had five young children to raise. Two-year-old Mary was packed off to nearby Malden, to be reared by a childless aunt and uncle. She later described these lonely formative years as a “slavery of poverty & ignorance & long orphanship,” yet Emerson took charge of her own education, reading widely in literature, philosophy, history, and the classics.

Thanks to a modest inheritance from her grandmother and namesake, Mary Emerson came into adulthood as a rarity in early America: a property-owning single woman who could afford to refuse at least one marriage proposal. By age 30 she had committed to dance to the “musick of my own imajanation” and set out to craft a rich life as a scholar, theologian, reform-minded idealist, and writer. (We have not corrected Emerson’s idiosyncratic spelling, a common trait in the writings of self-educated nineteenth-century women.) “Today read all the time . . . wakefullness. I seem to live. I pant for knowledge,” she declared in 1804. Yet throughout this generally solitary existence Emerson maintained an equally abundant and incessant exchange of ideas with others. Whether in the pages of her massive journals and letters or in face-to-face conversation, this life of the mind kept her young.

For more than half a century—1804 through 1858—Emerson authored an immense series of journals she called her “Almanacks.” Numbering more than one thousand manuscript pages, these writings offer a rare and prolific example of early American women’s scholarly production. Unlike the standard almanac genre, which typically relates matter-of-fact jots about daily life and the weather, Emerson conceived of her Almanacks as an expansive record of the mind, a place to work out her thoughts and, more important, to engage directly with others, including the authors of her vast reading. Written on loose sheets of letter paper that were then bound with thread to create booklets, they became compact parcels designed for sharing. For every ten manuscript leaves sewn together, she enclosed another leaf (or more) with one of her many letters. As Emerson confided to her dear friend Elizabeth Hoar, “My Almanak scraps . . . love to wander.”

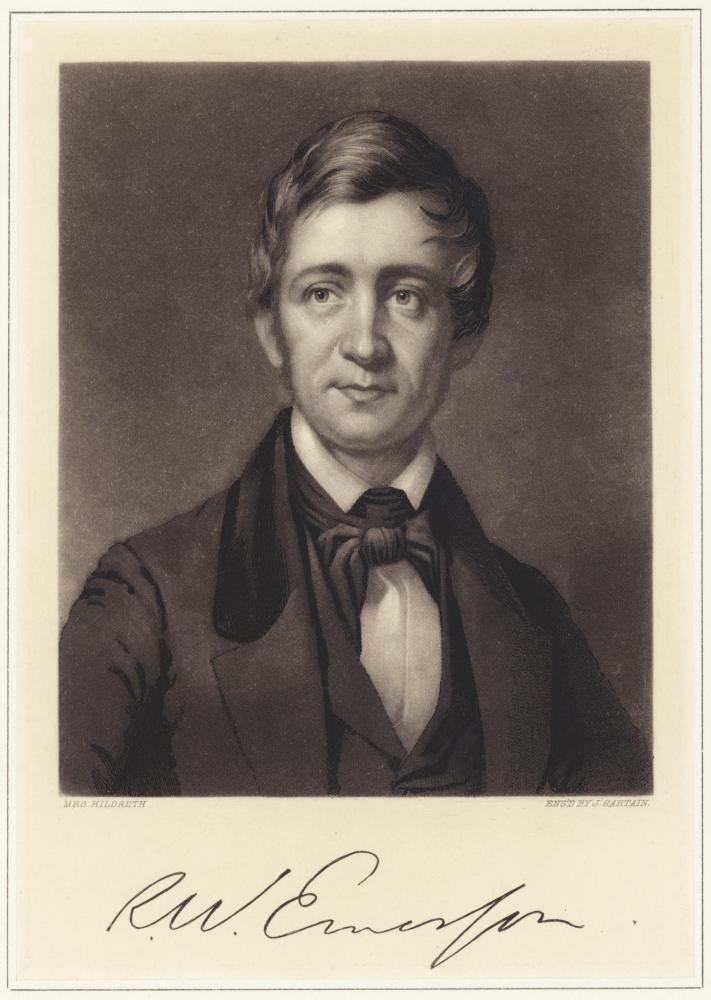

These traveling pages enabled a steady stream of conversation despite Emerson’s physical distance from loved ones. This gift for talk, later so esteemed by Thoreau, is manifest in nearly every Almanack entry, as Emerson engages in a “dialogic” approach to readers’ and writers’ mutual cultivation. Corresponding in March 1830 with nephew Charles Emerson, she mentions having recently enjoyed “much good talk with my learned Cousin,” as she referred to pioneering educator Joseph Emerson, and hopes to extend that experience to Charles by sending with the letter “an old page to make up talk.” The “old page” was an Almanack leaf on which Emerson imaginatively frames a hypothetical encounter “were Plato & Shakespear to meet!” Years before the Transcendentalists, led by Ralph Waldo Emerson, proposed that invigorating conversation on “higher truths” could generate individual and social reform, Mary Emerson pursued their exalted notions of “self-culture” via scintillating dialog with friends, family, chance acquaintances, and the authors she read.

What struck Thoreau as her ability to “entertain a large thought with hospitality” had long been Mary Emerson’s method of connecting with others, initially with Concord friends like Mary Wilder von Schalkwyck, with whom Emerson published a series of epistolary essays as a young woman; and later with intimates such as Sarah Alden Bradford, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Ann Sargent Gage, and Elizabeth Hoar, women 20 to 40 years her junior, as well as with her nephews, especially Waldo (as Ralph Waldo Emerson preferred to be called) and his brother Charles. Encouraging their own intellectual pursuits, Emerson asked constantly about the books her young friends were reading, including those she’d recommended but since changed her mind about. For example, she instructed Ann Gage that Germaine de Staël’s Germany was, on further thought, “not nessecary to your real improvement.” In an 1814 letter to future sister-in-law Sarah Alden Bradford, she insisted, “Write me more. Ever you read Dante? Why is that that his infernal reigions are so much more interesting than his celestial? . . . Do you love Tasso? Oh that you could write the history of all you know in miniature? a picture of Antient Greece from your hand, how wd [would] I idolise painting!”

Unlike many early American women’s manuscripts that haven’t survived, the Almanacks exist today almost certainly because of their value to Waldo Emerson, who at his request had inherited “the legacy of all” his aunt’s “recorded thot.” The Almanacks’ subsequent history, however, reads like a near fatality. In 1872, Waldo’s Concord home caught fire, severely damaging and massively disordering Mary’s writings along with other treasured family papers. Townsmen rushed to extinguish the blaze, while others, including neighbor Louisa May Alcott, rescued precious manuscripts, among them hundreds of Almanack leaves that lay smoldering and scattered on the lawn. When eventually deposited with other Emerson family collections at Harvard University’s Houghton Library, these fragile writings went into uncataloged storage, where they lay for decades until Phyllis Cole put them to use in Mary Moody Emerson and the Origins of Transcendentalism (1998).

As he matriculated at Harvard and then as he began his ministry, Waldo’s close relationship with his aunt is a prime example of the mentoring and repartee for which Mary Emerson was celebrated. During the 1820s, especially, their back-and-forth correspondence often spilled onto Almanack pages as the two took up all manner of inquiries. Their discussions ranged widely across subjects and figures—from natural religion, Russian poetry, Indian mysticism, and northern European mythology to Shakespeare, Plato, Kant, Byron, Cicero, and Coleridge, among a host of others. They besieged each other with requests confirming their vital need for this reciprocal storm of ideas: “Write to me, dear Waldo,” she pled; “I do beseech your charity not to withhold your pen,” he urged; and “Perhaps you are tired of my metaphors but I write to get answers not to please myself. . . . I beseech you again to write,” he repeated.

Mary’s nurturing of Waldo’s philosophical bent was vivid and profound. He later recalled that his aunt had “described the world of Plato, Spinoza, & all the ghosts, as if she had been mesmerized, & saw them objectively.” As a young minister, he found her “conversation & letters” better than all other research sources he consulted to write his sermons. Well into her seventies, Emerson continued to board in and around New England several months out of each year in search of good private libraries. Sarah Ripley portrayed this dynamo at age 70 as a piercing intellect who “enters into conversation with everybody, and talks on every subject; is sharp as a razor in her satire, and sees you through and through in a moment.”

Consistently, those conversations began with Emerson’s unquenchable curiosity to understand a younger generation’s state of mind—and to compare it with her own. “How is thy soul?” she inquired of Waldo in 1821. “Not that of which Paul speaks—but thy poetic? The spirits of inspiration are abroad tonight. I have rode only to go out & see the wonderous aspect of nature. Do we love poetry as we do the flowers of the field— . . . Fancy, celestial gift, is to the mind what those to earth.” This lyrical mental energy never diminished. Mary Emerson’s was a life conducted at full speed, Waldo observed, adding that she whirled at a “greater velocity than any of the other tops.”

True to Waldo’s depiction, Emerson tried her hand at a variety of literary genres. To this end, the Almanacks reveal an apprentice author’s literary miscellany—including devotional diaries, philosophical journals, commonplace notebooks, original compositions, and letters. In their pages she addresses an astounding range of subjects—from theology, philosophy, literary criticism, and science, to war, imperialism, women’s cultural roles, the perils of old age, prison reform, and slavery. Far from orthodox, her eclectic reading and admiration for liberal thinkers reflect a broad-minded theology infused with Enlightenment-era findings in natural philosophy and empiricism as well as Romanticism’s philosophical idealism and emphasis on the imagination. Indeed, in an 1827 Almanack, her melding of nature and science strikes a common chord with Thoreau: “What is most exciting the mystery of the variation of the magnetic needle w’h [which] still remains unexplained Why do I feel such delight that nature keeps secrets? . . . more proofs to me of the Author of nature being the Author of reve. [revelation]. And they excite curiosty w’h [which] never can be sated here. . . . Here is the poetry of nature & science.”

The Almanacks’ expanse of genres, some neglected or forgotten today but important to early American women writers, reminds us of what Thoreau well knew: Emerson’s youthful enthusiasm, insatiable thirst for ideas, and experimentation with the pen never faded. Because the Almanacks have usually been pigeonholed as spiritual diaries, their other literary models, each with its own interpretive lens, have largely been overlooked. Especially relevant to Emerson’s writings is the genre of the commonplace book, which promoted innately conversational opportunities for writers to extract, comment on, and arrange excerpts from their reading (called “commonplaces”) in new contexts. In producing these social forms of intellectual and material artistry, Emerson joined other young antebellum women whose pens weighed in on key public debates, including questions of the emerging public spheres of republicanism and liberalism.

But in the salon atmosphere of Emerson’s “talking” commonplaces, conversation played out as a creative game—one Germaine de Staël described similarly as a “lively exercise, in which subjects are played with like a ball, which in turn comes back to the hand of the thrower.” In de Staël’s manner, Emerson lobbed that ball far and wide, in page after page of her Almanacks. She insistently placed in dialog the authors of her reading for the same reason she entreated rising Transcendentalist star Frederic Henry Hedge to slake her “insatiable desire to understand” the “new school” in 1838. Shooting rapid-fire questions about his own and others’ publications, she reassured the younger man, “Now my dear Sir, dont answer me as if I were a timid old woman & would boast of your sayings or be alarmed.” At the heart of these conversations lay her fervent impulse to keep the ball in play—to illuminate her own boundless forays with another mind’s fires.

This hunger for enlightening dialog emerges most clearly in the Almanacks’ commonplacing from the poets, philosophers, and theologians Emerson most admires—among them, William Wordsworth, Dugald Stewart, Jonathan Edwards, Victor Cousin, Adam Smith, John Locke, Samuel Clarke, and Richard Price. At times, she aligns these figures to debate each other; at others, she questions them herself. Emerson’s typical writing practice was to copy a key phrase or two from her reading into a notebook, then to consider and reconsider these ideas in a running classroom discussion as though the authors sat in the room with her. Whether venerating or admonishing, Emerson politely addresses a host of figures—from “dear immortal [Samuel] Clark,” to “Dear sainted Plotinus,” to “dear Mrs Hemans,” to “dear Cole.[ridge],” to “dear Plato,” to “Dear cautious modest old gentleman,” as she referred to Scottish Common Sense philosopher Dugald Stewart, to “Old Hume . . . the old Sophist.”

She relates her exhilaration at this process in March 1835 with the explicit classical trope for commonplacing, the image of the diligent bee, flitting from flower to flower while culling the sweetest nectar for its honey. “This holiday of soul I beginn the 1st vol. of [Victor] Cousin . . . get scraps & write them down as the buzzing fly sips from the rich floweret,” although she later qualifies this initial excitement: “Tis’ pity Cousin is a catholic.” In 1827 Waldo encapsulated what she had taught by example: “To ask questions, is what this life is for,—to answer them the next.” The open-ended spirit that infused these sallies comes across in an 1820 letter to Waldo. “How do you, dear play Mate? . . . Do write. . . . Write I say—Colledge news—that will be literary—but above all about yourself—a very important personage to me.”

Other recipients of Emerson’s conversational prowess shared Thoreau’s glowing reaction to his thoughtful discussions with the “youngest person in Concord.” Transcendentalist Elizabeth Palmer Peabody marveled that Emerson, thirty years her senior, seemed never to tire but to “coquette with life like a girl of fifteen.” In a vibrant exchange recorded directly on the pages of Emerson’s 1829–1830 Almanack, family friend Ellen Ward Blake Blood, some thirty years Emerson’s junior, responds warmly to Emerson’s description of a fervent “hunt” for a “Truth” that directly “leads . . . to the Center of all truth & being.” Emerson sketches this quest autobiographically by depicting herself as a “book scavanger” cast adrift on a “vast ocean”—seemingly life’s voyage—on an “unrigged” and “unoared” boat as she steers her course toward the vocational “pursuit” of “knowledge.” Her decades of commonplacing become heroic: “Courage and go on to the mystifying work of years—transcribing . . . But to thy task slave—boatwoman—cabin rotter—book scavanger! . . . Too it, to it!” After reading these borrowed Almanack pages, Ellen Blood picked up her pen, first to praise Emerson’s self-possession and then to offer her own commonplace extract to converse on the page with Emerson’s. Honoring her as “the author of these fragments,” Blood extolls Emerson as a woman whose “faith is fixed,” whose “business is improvement of her mental & moral powers,” and “whose felicity is within herself.”

The Almanacks also bear witness to Emerson as an engaged citizen, particularly with antebellum reform causes more consistently embraced by a younger generation of firebrands. She contributed financially to charitable causes, including Boston’s Female Asylum and a school for destitute women. While her antislavery views are evident as early as 1827, she allied with radical abolitionism in 1835 after listening to a rousing speech by Charles Burleigh, an intense young acolyte of Boston’s controversial abolitionist leader, William Lloyd Garrison. Quite often, the likes of Burleigh moved Emerson far more than traditional Sunday sermons, about which she is often critical. Suffering listlessly through one minister’s homily at this time, she is thankful that “the young man for emancipation raised me to the top of my being. God bless him.” It was infectious and high-minded oration that reached Emerson at any age.

Emerson both praised and scorned others for the strength of their antislavery activism. Lydia Maria Child, author and editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard, for example, merited admiration for frankly confronting slavery’s injustice and attendant horrors; yet Emerson found fault with Concord relatives, including Waldo Emerson and his family, for their initial silence when the Fugitive Slave Act became law in 1850. No cause, including antislavery, was ever Emerson’s chief concern, but her acute reform sympathies more often than not found her allied with younger, more radical “hotheads” than with the decorous conservatives and moderates of her own generation.

In early 1861, Waldo’s daughter Ellen Emerson, age 22, spent several days with her ailing and frail great aunt, now 87 years old. Part of Ellen’s mission during this visit was to procure more of the Almanacks, and, if possible, to learn the location of others. On being asked the whereabouts of the manuscripts, Mary Emerson “trotted up to” a chest and invited Ellen not only to take “piles of journals,” but to help herself to cherished family letters and other heirlooms as well. A triumphant Ellen returned home to Concord and regaled her family with more treasure from her visit—“story after story, all new, about the Ancestors,” many of them unfamiliar even to her father. Ellen’s euphoria mirrors Thoreau’s pleasure in talking with Emerson six years before. Descriptions of the elderly Mary Moody Emerson recall her as ageless, riding horseback and “with rosy skin that never wrinkled, and bobbed yellow hair that never grayed.” At age 81, she was not, of course, “the youngest person in Concord.” But with her provocative mind and youthful temperament, figuratively speaking at least, Thoreau may have been right.