On a mid-August day with a heat index of 115 degrees, in a rental car with slow pickup, I drive through the Orlando suburbs searching for Eatonville, a three-square-mile town of 2,400 residents. I keep getting lost. Finally a brown “Eatonville Historic District” sign appears, and fifteen miles later it dawns on me that I have gone too far. I turn back, find the city limits, and enter Eatonville. At the “Welcome to Maitland” sign, I realize I have driven through the entire town. It took three minutes.

It may be small and hard to find, but Eatonville is important for two reasons: It was the first all-black incorporated town in the United States, and it was the childhood home of Zora Neale Hurston. Much of Hurston’s writing is set here, and many of her characters are thinly disguised versions of actual residents. Eatonville gave Hurston her best material, and a few years ago, the favor was returned. The Hurston connection gave Eatonville an argument to save itself from being paved over. Hurston and Eatonville have always been closely linked: to understand one, you have to understand the other.

Formed after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, Eatonville was named after Josiah Eaton, a white army captain living in Maitland. During Maitland’s first civic election, a black man, Joe Clarke, was elected town marshal. As Hurston tells it in her 1942 autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, “I do not know whether it was the numerical superiority of the Negroes, or whether some of the Whites, out of deep feeling, threw their votes to the Negro side.” A year later, Clarke decided to create a separate all-black town, and Eaton supported him, as did Lewis Lawrence, a white philanthropist from New York City. Land was donated, then a church and a town hall were built. In Dust TracksHurston tells it this way: “On August 18, 1886, the Negro town . . . received its charter of incorporation from the state capital at Tallahassee, and made history by becoming the first of its kind in America, and perhaps in the world. So, in a raw, bustling frontier, the experiment of self-government for Negroes was tried. White Maitland and Negro Eatonville have lived side by side for fifty-five years without a single instance of enmity.”

Hurston is emphatic about her start in Eatonville and its identity as a black town. In Dust Tracksshe stated that she “was born in a Negro town. I do not mean by that the black back-side of an average town. Eatonville, Florida, is, and was at the time of my birth, a pure Negro town—charter, mayor, council, town marshal and all.”

Actually, Hurston was born in Alabama. The family moved to Eatonville when Zora was one year old, after her father, John, heard of the town and its opportunities for African Americans. He bought five acres and built an eight-room house. Hurston’s childhood was full of children playing outside, homegrown food, and fishing. Hers was not a struggling family. The town was dominated by churches, but its hub was Joe Clarke’s store, “the heart and spring of the town.”

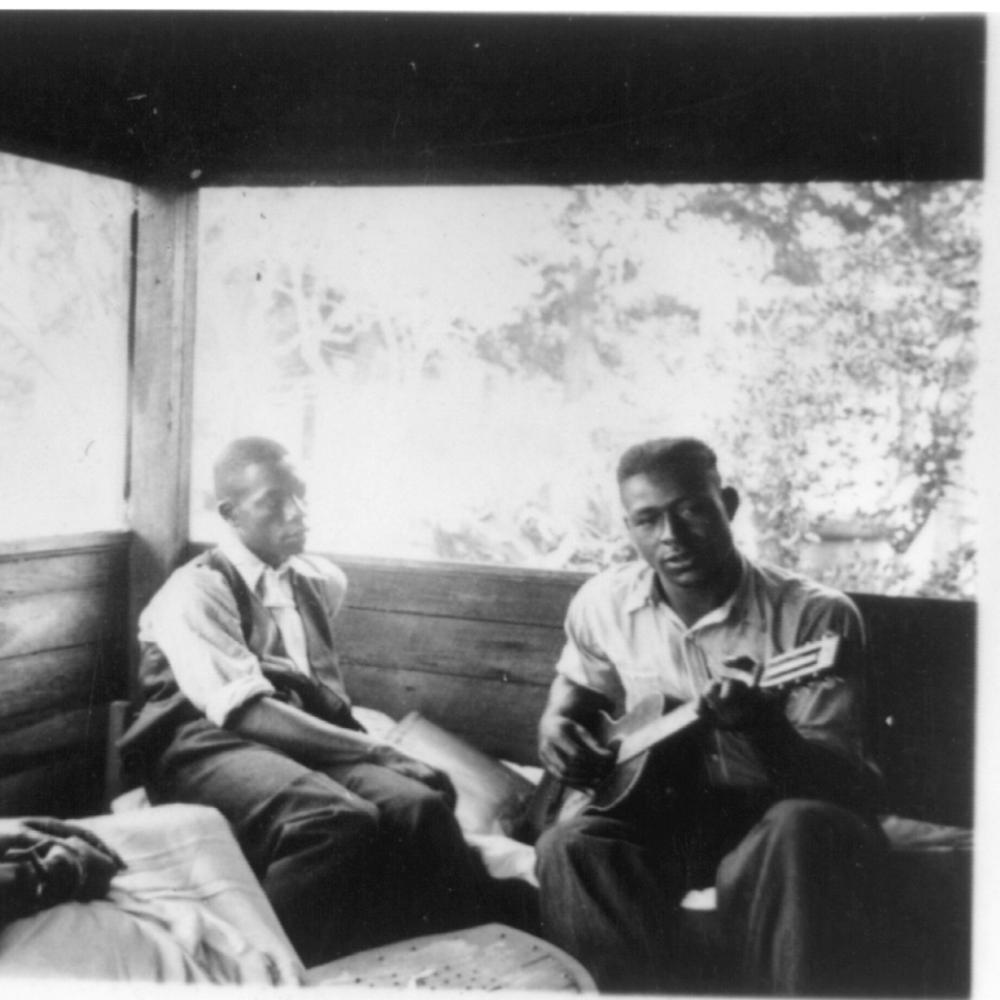

Men sat around the store on boxes and benches and passed this world and the next one through their mouths. The right and the wrong, the who, when and why was passed on, and nobody doubted the conclusions. Women stood around there on Saturday nights and had it proven to the community that their husbands were good providers, put all of his money in his wife’s hands and generally glorified her. Or right there before everybody it was revealed that he was keeping some other woman by the things the other woman was allowed to buy on his account. No doubt a few men found that their wives had a brand-new pair of shoes oftener than he could afford it, and wondered what she did with her time while he was off at work. Sometimes he didn’t have to wonder. There were no discreet nuances of life on Joe Clarke’s porch. There was open kindnesses, anger, hate, love, envy and its kinfolks, but all emotions were naked, and nakedly arrived at. It was a case of ‘make it and take it.’ You got what your strengths would bring you.

Eatonville did not encourage illusions about human kindness. On the porch, men bragged about beating their wives. This take-it-or-leave-it life was full of roughness, but it was not without pleasure. Only you had to find the good parts for yourself.

Hurston loved her hometown, but she never idealized it. Growing up there, she felt different, as if she stood apart from the other children and her family. “Often I was in some lonesome wilderness, suffering strange things and agonies while other children in the same yard played without a care. I asked myself why me? Why? Why? A cosmic loneliness was my shadow. Nothing and nobody around me really touched me.”

Luckily, her mother understood and indulged Zora’s desire to read and study. She died while Zora was still young, and after her death Zora was sent away from Eatonville. The years that followed were a struggle. In Jacksonville, she attended school, where racism was overt and “made me know that I was a little colored girl.” Her father quickly remarried—to a woman who did not like her new stepchildren. Returning to Eatonville, Hurston got into a violent fight with her stepmother, and so left home again.

As Valerie Boyd writes in her biography, Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston, “She not only vanished from Eatonville but also from the public record. Exhaustive searches of archives from this period have unearthed no census listing, no city directory entry, no school file, no marriage license and no hospital report. . . . In 1911, it was relatively easy for someone, particularly a black woman, to evade history’s recording gaze.”

Hurston describes these years as a jumble of service jobs and intense poverty relieved occasionally by periods of happiness, as when she worked as a maid for a white actress in a traveling theater troupe. She wanted to finish high school, and eventually enrolled in Morgan Academy in Baltimore. She lied about her age, excising ten years, claiming she was sixteen, so she could qualify.

She excelled at Morgan, moved on to Howard Prep and then to Howard University, where she received an associate’s degree in 1920. She began to write, and published some short stories in literary magazines. In 1925, she was admitted into Barnard College to study with Franz Boas, the leading anthropologist of the day. She began the first of many major field trips for Boas and others. Her first project was measuring head sizes in Harlem, which Boas asked her to do to help him discredit phrenology. Hurston was suddenly living a very unusual life, and a remarkably successful one for a black woman.

To many, Hurston is known primarily for her involvement with the Harlem Renaissance. During this time she befriended Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Wallace Thurman, and others, cooking them fried shrimp in her apartment, often a site for impromptu parties. But she quickly moved on. She was not a joiner of movements or trends. Like her hometown, Hurston was iconoclastic.

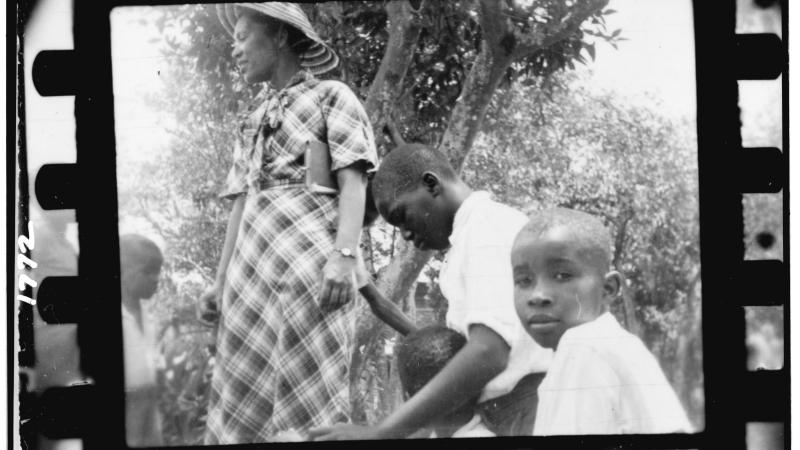

She spent many years doing anthropological field work, living on her own among strangers. She moved back to Florida, to Polk County, to do research in 1927, and from there traveled to New Orleans and the Bahamas. Later she would live in Jamaica and Haiti, spending time with voodoo doctors and learning about zombies, taking on unconventional and often dangerous field work that few would consider undertaking even today.

She had restless energy, no doubt, and the marriage of “cosmic loneliness” and love of the Southern black community is evident in many of her works and life decisions. She wrote plays, nonfiction, short stories, and an academic study of black folk life. She moved constantly.

After her mother died, she had little contact with her family, and, although she married a few times, her relationships were all short-lived. As a writer, however, she was tenacious. As Boyd points out, by 1933, Hurston was the only black woman in the country still striving to make a living off writing.

Despite her peripatetic ways and expansive interests, she returned often to her childhood and Eatonville, at least in her writing. In the 1930s—after the Harlem Renaissance—she published her first book. One of her many side projects, Jonah’s Gourd Vine is a novel about a fictional all-black town that looks a lot like Eatonville and the man who was once its mayor, who closely resembles her father.

The novel was well-received, but its timing was unfortunate. The Great Depression was on, and the Harlem scene had already dissipated. The black intelligentsia was moving politically leftward, while Hurston, as was her wont, went her own way. She leaned right, and wrote against race nationalism as well as the strident politics of Richard Wright.

Away from Harlem, she became more and more productive. Mules and Men, her groundbreaking work of cultural anthropology, was finally published in 1935. The next year, she received a Guggenheim Award to travel to Jamaica and Haiti to do more field work. Once again, a side project would bring her acclaim: During a seven-week period, while she was studying voodoo and zombies in Haiti, she wrote Their Eyes Were Watching God, her best-received work up to that point, and, today, a classic of American literature frequently taught in high schools and colleges. Like Jonah’s Gourd Vine and many of her short stories, it hews closely to her experiences in Eatonville.

She was famous but still poor. In 1938, she worked for the WPA, receiving a government check for field work she did in Florida. For a while she lived on a boat, and, in 1941, worked briefly for Paramount Pictures, earning $100 a month, the highest salary she would ever earn. In 1942, she published Dust Tracks on a Road. It won the Anisfield-Wolf award for best book on racial relations and came with a $1,000 award, the largest single-sum payment she would ever receive.

In 1948, she moved back to New York briefly, where she was falsely accused of molesting a boy. The case made headlines, and hurt her reputation, even though the boy recanted and charges were dropped. Her next book, Seraph on the Sewanee did not sell well.

Hurston lived the rest of her life back in Florida. She briefly worked as a domestic to pay her bills. She published political articles in which she explained her conservative views and campaigned for Republican candidates. In 1955, she wrote against the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling, because she opposed forced integration: The ruling was “insulting rather than honoring my race.” In Fort Pierce, Florida, she found a new community, and she worked as a substitute teacher and went on welfare. In 1959, she suffered a stroke and died at St. Lucie County Welfare Home in 1960.

Most of her work fell out of print. In 1973, Alice Walker went to find her grave and wrote about it, and a biography in 1980 brought Hurston further attention. In Fort Pierce, where the community raised funds for her casket and funeral, the town created a Dust Tracks heritage trail to draw in tourists.

But Eatonville, not Fort Pierce, is the source of much of Hurston’s fiction and the explanation, perhaps, for her independent streak, her love of folklore, and her unlikely political views. As Boyd argues, being raised in an all-black town was so formative and positive that Hurston distrusted “forcible association” between races. Boyd quotes another person who says Eatonville was “like a four-walled room.” Inside the room black people lived unseen and unexamined by white people. It was the primary setting for her life and her fiction, a “city of five lakes, three croquet courts, three hundred brown skins, three hundred good swimmers, plenty guavas, two schools, and no jail-house.”

These days, Eatonville is a struggling small town. Every year it holds a very successful and well-attended ZORA! festival. But the school has closed, and the poverty rate is twice that of the rest of the country. That the town still exists seems remarkable. In the 1980s, the state planned to run a highway through it. Eatonville residents banded together and, emphasizing the town’s historic roots and its connection to Hurston’s life and writing, successfully lobbied to have the road rerouted. They won. Without Hurston to champion, the town would probably be gone today.

In 2008, the town had a new streetscape installed. A half-mile stretch of Kennedy Boulevard is now brick, flanked by new landscaping, and the utility lines are buried. The new main drag is certainly handsome, but also dissonant. Usually such urban improvements are accompanied by other redevelopments: new buildings, condos, and shopping malls. While there are a few of those on Kennedy Boulevard, notably the library, many of the buildings are in need of repair. An aging sign for the local motel, suggesting an unlikely, Vegas-style glory, is half-hidden behind overgrowth; the place itself has neither a website nor a welcoming feel. A 1970s mural depicting famous African Americans is fading. A decrepit house, the oldest in town, bears a sign with a large “ZORA!” written on it. Hurston never lived there, but for lack of another identity it claims her.

The buildings may be depressing, but Eatonville has a lot of pedestrian life. On that sweltering Saturday, when I drove through, I saw many people out and about. A church was holding a picnic, complete with bouncy house and carnival games. Boys were riding bikes, doubled-up, on the side streets. And even though I looked conspicuous when I parked my rental car and took out my camera, no one looked at me askance. I had lunch in Lowe’s Good Eaton—smothered pork chops, greens, black-eyed peas, and cornbread. I asked a few diners if I could take their picture, and they nodded sure. They were not surprised by my request, nor did they ask why. Eatonville may not be prettified, and it may be a little bit of this and a little bit of that, but it is self-confident and aware of its heritage. Not unlike its most famous citizen.

I am far from the only person who comes to Eatonville to learn more about its famous author. Four summers in a row, the town has hosted schoolteachers in an NEH Landmarks of American History Workshop, “Zora Neale Hurston and Her Eatonville Roots.” Lead scholar Heather Russell, associate professor of English at Florida International University, says the teachers always return to the same dialectic, wondering, “Is Eatonville the most important thing about Zora Neale Hurston, or is Zora Neale Hurston the most important thing about Eatonville?”

During my brief visit, I could only glimpse some of the complications the NEH seminar encourages. But like many visitors, I wondered whether the town could be doing more with its rich literary legacy. Then again, the problem with a lot of literary tourism is that the message has already been spelled out. Simplifications are printed on celebratory plaques, and the nicest buildings are foregrounded and photoshopped. The shiny souvenir gets mistaken for the real thing, and the words on the page are forgotten.

But in Eatonville, the homely face of a struggling neighborhood has not been dolled up. Hurston’s hometown may not be keeping pace with Fort Pierce in terms of cultural heritage or Orlando in terms of tourism, but it is not hiding behind a false façade. As a result, it is very easy to see how Hurston came from such a place, and why it was such a compelling and rich source for her fiction.

I drove back across the highway, one of many, and returned to my air-conditioned hotel room—a room like a hundred others in a chain like a hundred others. I read Dust Tracksin the mauve lounge while a baseball game played on the flat screen behind the bar. Eatonville’s unreadable plaques, fading murals, and boys on bicycles were, by contrast, far more memorable and vivid, as are, still today, Hurston’s words on the page.