A rare, centuries-old Moorish saddle somehow made its way from North Africa to Spain, and then survived an ocean crossing to land in what is now Texas. Its construction is unique and beautiful: The cover is made of wood and rawhide, the horn and cantle are covered in alligator skin, and it would have originally been padded with wool and horsehair. The saddle, on loan to the Grace Museum in Abilene, is featured among artifacts and paintings from dozens of collections in “Spanish Texas: Legend & Legacy.” The exhibition looks closely at how the culture and art of the conquistadors, vaqueros, and Spanish missions have left their lasting mark on Texas.

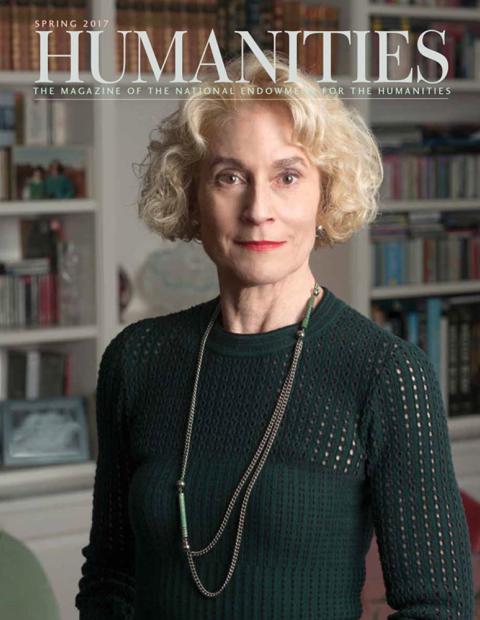

“Spanish Texas,” supported by Humanities Texas, is the result of years of effort by the Grace Museum’s curatorial team to put together an exhibition tracing the cultural hybrid of Spanish, Mexican, Anglo-American, and Native American traditions that make up modern Texas.

It began with the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in Texas in the sixteenth century and the establishment of Nueva España. Explorers armed with only the vaguest of maps (a number of which are currently on view at the Grace) and a misguided search for fortune, set off on a quest to colonize the “The Great Space of Land Unknown,” as Texas was labeled on maps of the period. For more than a century the Spaniards ruled Texas as a province, establishing 26 missions and a number of presidios and, in the process, spread their architecture, their religion, and their farming and industrial methods. The first floor of the Grace Museum’s exhibition chronicles those early roots and shows the coexistence of Spanish and Mexican art and culture in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Weapons, art—such as the small retablos and sculptures of saints common in Mexico even today—and illustrations of Spanish missions adorn a gallery showing the initial meeting of Mexican and Spanish cultures and the centrality of religion to daily life.

Upstairs, the exhibition looks at Texas under Mexican rule. The Mexican War of Independence, which stretched from 1810–1821, shook up the balance of power in Texas yet again, establishing Texas as a province of Mexico until Texas declared its independence in 1836 and then became part of the United States in 1845. “Historical events that shape culture are always worth revisiting,” points out Grace Museum Chief Curator Judy Tedford Deaton. These brief years saw more aspects of Mexican culture take root, especially the strong culture of the vaqueros.

The history of the vaquero, Spanish for cowboy, is detailed in the exhibit through portraits and illustrations by Mexican and European artists depicting vaquero music, colorful costumes, and celebrations. Most Texan livestock handling techniques used to this day derive from the Mexican vaquero, and the origins of the Texas cowboy’s penchant for display—evidenced through rodeo and competition—are seen in the saddles, ropes, and other beautifully handcrafted artifacts that remain, such as the one originally from North Africa. These artifacts, alongside the paintings and even a number of photographs from the period, help visitors imagine life in nineteenth-century Texas.

Both European and local artists, attracted to the region by government and private commissions, have interpreted the changing cultural heritage of the region. German artist Hermann Lungkwitz, Deaton explains, came to Texas and became a photographer for the General Land Office and painted romantic landscapes of nineteenth-century San Antonio, the Hill Country, and missions.

Paintings and drawings chronicle centuries of life in Texas and offer different perspectives. Two works by Leon Trousset, an itinerant painter from France who spent time working in Texas in the late nineteenth century, are on view next to a work by Porfirio Salinas, a son of Mexican-American tenant farmers who learned to paint by working in the studio of a local English painter. Where Trousset adopted some of the folk art techniques native to Mexico and Texas to paint the people and landscapes of El Paso, Salinas’s paintings are more indebted to European Impressionism. José Arpa y Perea is another artist represented in the exhibition. A Spaniard who founded a painting school in the 1920s, Arpa influenced many artists, including Salinas, with his light-infused landscape painting.

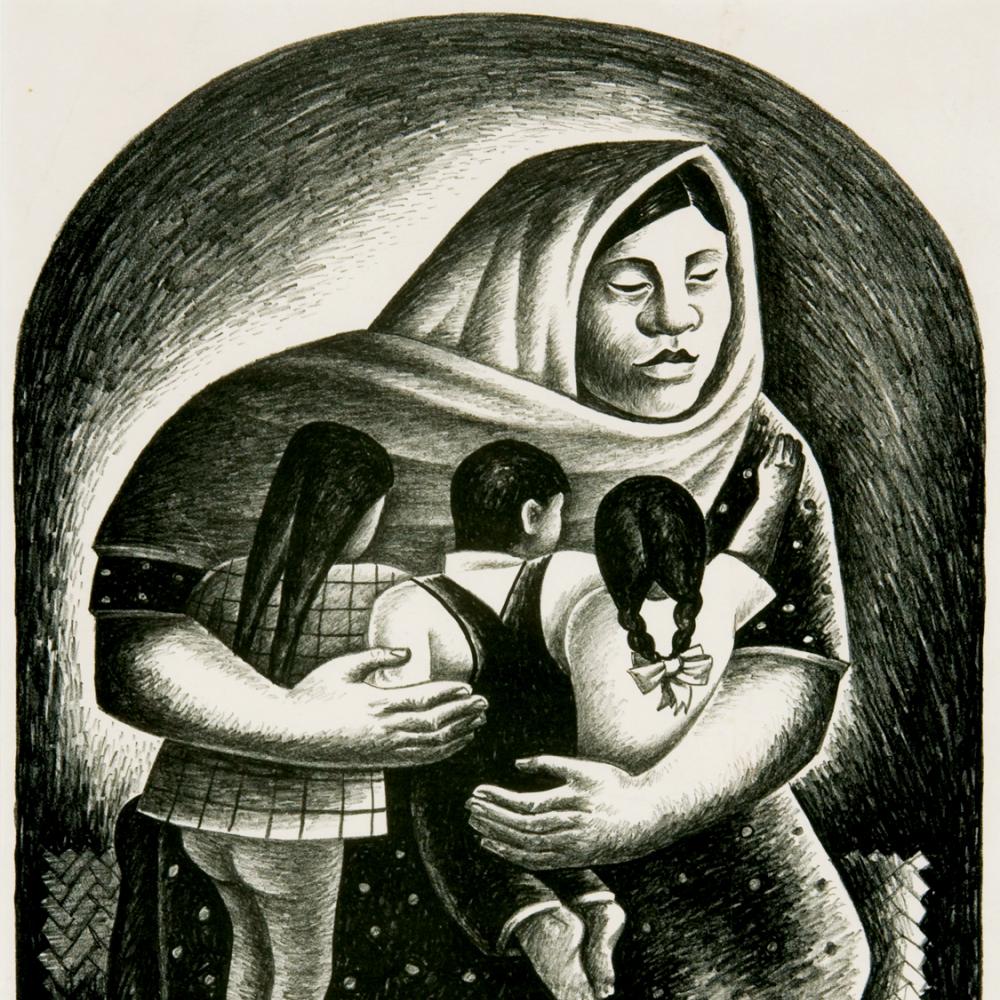

Works by more recent artists are also on view, including a number of paintings by José Cisneros documenting Mexican leaders and vaqueros. A detail from Tom Lea’s masterful Pass of the North, a mural Lea completed in 1938 for the historic federal courthouse in El Paso, is reproduced at the exhibition’s opening; the image’s modernist portrayal of a Spanish padre, vaquero, and conquistador summarize the dominant elements of the exhibition.

The final segment of the show explores contemporary ways in which Mexican and Spanish art and culture have seamlessly blended into Texas culture. Culinary artifacts such as knives, iron utensils, even a metate, used to grind maize for tortillas, brought to Texas from Mexico, showcase the elements that created Tex-Mex cuisine. Nearby, a cowhide rug, an exquisite horsehair rope, and ceramic vases, plates, and bowls illustrate the ways Spanish and Mexican farming practices and craftsmanship have influenced the arts and crafts Texans now call their own.

The rich history of Abilene itself is documented through city maps, early photographs, newspaper articles, and an oral history video featuring the reflections of Melinda Carrillo Stone, an Abilene native and community leader, whose originally Mexican family ran a beloved restaurant in Abilene for many years. “The construction of the Texas and Pacific Railway brought many Mexican migrant workers to Abilene in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,” Deaton says, “Those who stayed grew with the community as business owners, educators, and professionals in the public and private sector.” By concluding with a focus on the community of Abilene, one city among many, Spanish Texas offers a reminder that while the cultural origins of Texas can be seen everywhere, they’re most evident in the people who call Texas home.