The Odyssey and an illustrated biography of Susan B. Anthony are very different books, but New Hampshire Humanities is using both as tools to serve its rural but increasingly diverse state. The biography and other award-winning children’s books are the focal point of adult literacy discussion groups for English-language learners, people with cognitive disabilities, and anyone else who wants to improve their reading skills. The Odyssey, meanwhile, is helping veterans process what they experienced on the battlefield and beyond. The book is roughly 3,000 years old, but Deborah Watrous, the executive director of New Hampshire Humanities, says the story is packed with metaphors that help modern service members make sense of such themes as honor, duty, and sacrifice.

“It’s a perfect example of how powerful the humanities are,” she says.

Called “From Troy to Baghdad: Dialogues on the Experience of War and Homecoming,” the project guides groups of veterans through discussions based on the Odyssey. Each group features three facilitators: a veteran, a therapist, and a literary scholar. “Those vets, when they read and talk about it, they’re seeing their own experiences and there’s enough distance that there are not triggers, but they can see the universal aspects of war,” says Watrous.

The groups are limited to veterans and their families, but word of the project has spread much wider thanks to coverage in the local media. When participants were featured on a New Hampshire Public Radio show called The Exchange, listeners enjoyed the discussion so much they voted the episode the best of 2016.

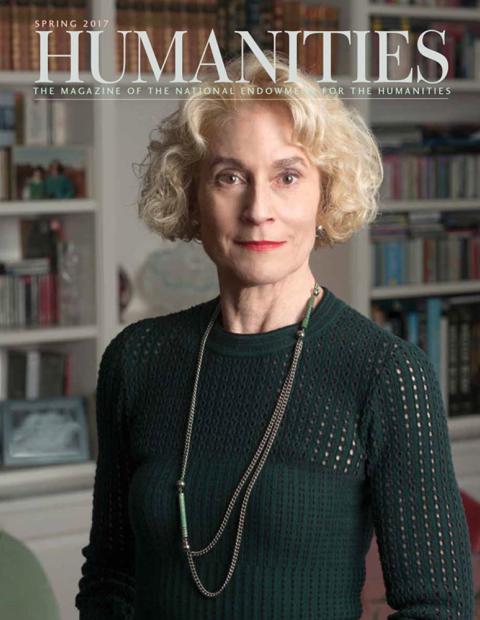

Watrous joined the humanities council as development director in 1990 and, except for a year at home with young children and a brief stint at a local community college in the early 2000s, has been there ever since, working as special projects director and associate director before becoming executive director in 2004. She holds a master’s degree in voice performance from the University of Cincinnati’s College Conservatory of Music and a bachelor’s in music from Kirkland College in Clinton, New York. In her free time, Watrous still sings in the local community chorale.

Discussion groups and cultural events are the bedrock of New Hampshire Humanities’s work, but Watrous and her staff are also expanding their digital reach to better serve every corner of a state known for both its civic engagement and its deep affinity for local control.

Facebook helps build a sense of community across geographic distance, as do Twitter and, more recently, Instagram. And, with the help of an NEH Challenge Grant and its private match, the council is designing the kind of videos, contextual information, and digital artifacts that Watrous hopes will attract younger patrons. But, when it comes to the actual events, Watrous and her colleagues push for plenty of human interaction.

“When you’re in face-to-face conversations, it’s messy,” Watrous says. “People are complicated. Issues are complicated. One of the beautiful things that the humanities can do is to introduce you to those complexities.”

While Watrous plans to continue to use emerging technologies to reach New Hampshire residents, she has no plans to add online discussion boards or chat rooms to the mix. “So far, those aren’t very successful,” she says. “There’s not civil, thoughtful conversation happening out there in cyberspace. Just the opposite.”

New Hampshire’s robust civic life fosters interest in events about politics, history, and culture, but Granite Staters’ attachment to small government means the only state support the council receives is office space in the state’s capital. Money for programs comes largely from donors. “We have been aggressive fundraisers for a long time,” Watrous says. “We rely on private support.”

There’s no humanities center, so libraries and schools routinely serve as venues for cultural events, and it’s often the tiniest towns that turn out the biggest crowds. Those communities, Watrous says, have limited access to cultural programming.

“Our programming is truly distributed,” Watrous says. “Even when we create special initiatives that we design ourselves, they’re happening with local partners and local communities. We can truly have a statewide impact.”

The main vehicle for local programming is Humanities to Go, a project that brings cultural events to local communities. The subject matter is diverse: Witchcraft, the history of health care, and the state’s long relationship with skiing are just a few examples of the 450 talks booked each year.

Some of these programs are tailored to New Hampshire’s changing demographics. In the last decade, thousands of refugees from places like Somalia, Croatia, and Bhutan have moved to New Hampshire, creating an opportunity to explore issues around immigration through lectures that explore how newcomers have shaped the state over the past two centuries.

The adult literacy discussion groups are a favorite among members of the refugee community, giving people from very different backgrounds a chance to meet.

“Some of them are in citizenship classes, some are getting their GEDs. It’s an incredible range,” she says. “We may have people who speak five languages.”

**********************************

Tell me more, Deborah

What do you most like to sing? Brahms’s Requiem is one of the most moving choral works ever composed, in my humble opinion. I performed it in college and am thrilled to be doing it again with the Concord Chorale in May. There is nothing more joyful than singing in a choir.

Most thrilling professional moment? Meeting Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

The piece of art that takes your breath away? Michelangelo’s David.

If you could chat with anyone past or present, who would it be and what would you talk about? I would love to talk with J. S. Bach, someone who created some of the most sublime music every composed. How did he access that creativity in the midst of the daily grind of making a living to support a large family, serving cranky church leaders, negotiating temperamental musicians, and accounting for the technological challenges of the instruments of the day?

If you did not live in New Hampshire, where might you like to live? The Istrian Peninsula in Croatia. It is right across the Adriatic from Venice. There’s a Roman colosseum, fabulous local olive oil and truffles, lovely beaches, beautiful little villages, and an easygoing pace. What more could I ask for?