Marching on Washington may seem an obvious recourse for a national protest movement today, but it wasn’t until more than a century after the District of Columbia’s founding in 1791 that protesters first marched on the Capitol. The Humanities Council of Washington, D.C., is marking the city’s 225th anniversary this year with a series of panel discussions, including one held in August on the history of protest in the district. Panel members included Glenn Marcus, a historian who produced a D.C. Humanities-supported PBS documentary on the Bonus March of 1932; Dorie Ladner, veteran of the civil rights movement in the South, who participated in the 1963 March on Washington; and Parisa Norouzi, cofounder of the advocacy group Empower D.C.

In 1893, members of the short-lived Populist Party, led by Ohio businessman Jacob Coxey, demanded government jobs and public investment in response to the hard times of the 1890s. Dubbed Coxey’s Army, they were mocked by the press and struggled to make their way to D.C. Two men were killed in a confrontation with federal marshals after a contingent of Coxeyites commandeered a train in Montana, and, once Coxey arrived from Ohio with 500 men, members of Congress contested the protesters’ very right to air their grievances. Coxey and others were eventually arrested. L. Frank Baum likely drew inspiration from these events for his 1900 children’s novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Like Dorothy and company, the Coxeyites reached their goal, but left disappointed and disillusioned.

Still, as Lucy Barber argues in her book Marching on Washington (based on her NEH-supported doctoral dissertation), Coxey’s Army drew national attention to its cause and established the idea that the disaffected could come to the seat of the federal government directly to have their grievances heard.

When the Bonus Army—a group of World War I veterans out of work during the Depression and demanding early payment of their service bonuses—marched on Washington in the summer of 1932, they received a much better reception, at least initially. Twenty thousand veterans from across the country camped throughout the district and built a shantytown just across the Anacostia River. They marched peacefully on the Capitol and lobbied representatives directly at their offices. But after the Senate voted down the Bonus Bill and the occupation stretched into its second month, federal tolerance began to wane.

As Marcus emphasized, both President Hoover and Army Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur became convinced that Communists had permeated the group. Also alarming was the presence of a significant number of black veterans, who were integrated with their white colleagues in unprecedented fashion. This was perceived as a “tremendous threat,” Marcus said.

Finally, after Congress adjourned, the administration moved to have the marchers evicted from their camps by police. Two protesters were shot during an altercation at one of the camps, leading Hoover to call in MacArthur’s troops. The veterans, who, as Marcus pointed out, had endured tear-gas attacks in the trenches of Europe, were again teargassed, this time by their fellow soldiers. Against Hoover’s orders, MacArthur marched his troops across the bridge into Anacostia and set fire to the marchers’ camp.

Despite its horrific ending, the Bonus Army “laid the groundwork” for the massive civil rights and antiwar protests of the second half of the twentieth century, according to Marcus. “It showed that citizens could come and have their voice heard in the spaces around the Capitol,” and established D.C. as a “demonstration space.” The Bonus Bill was eventually passed in 1936 (over Franklin Roosevelt’s veto), and the Bonus Army’s example prompted the drafting of the 1944 GI Bill, which ensured World War II veterans would be better compensated for their service.

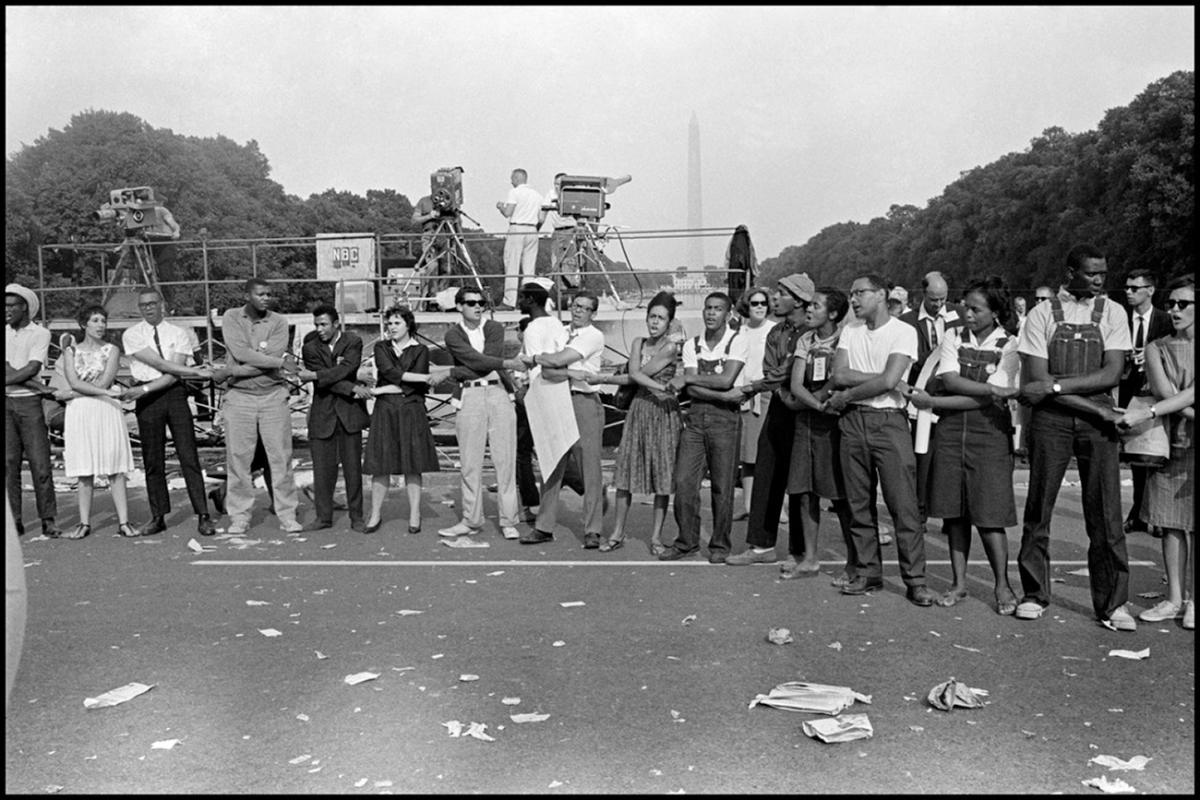

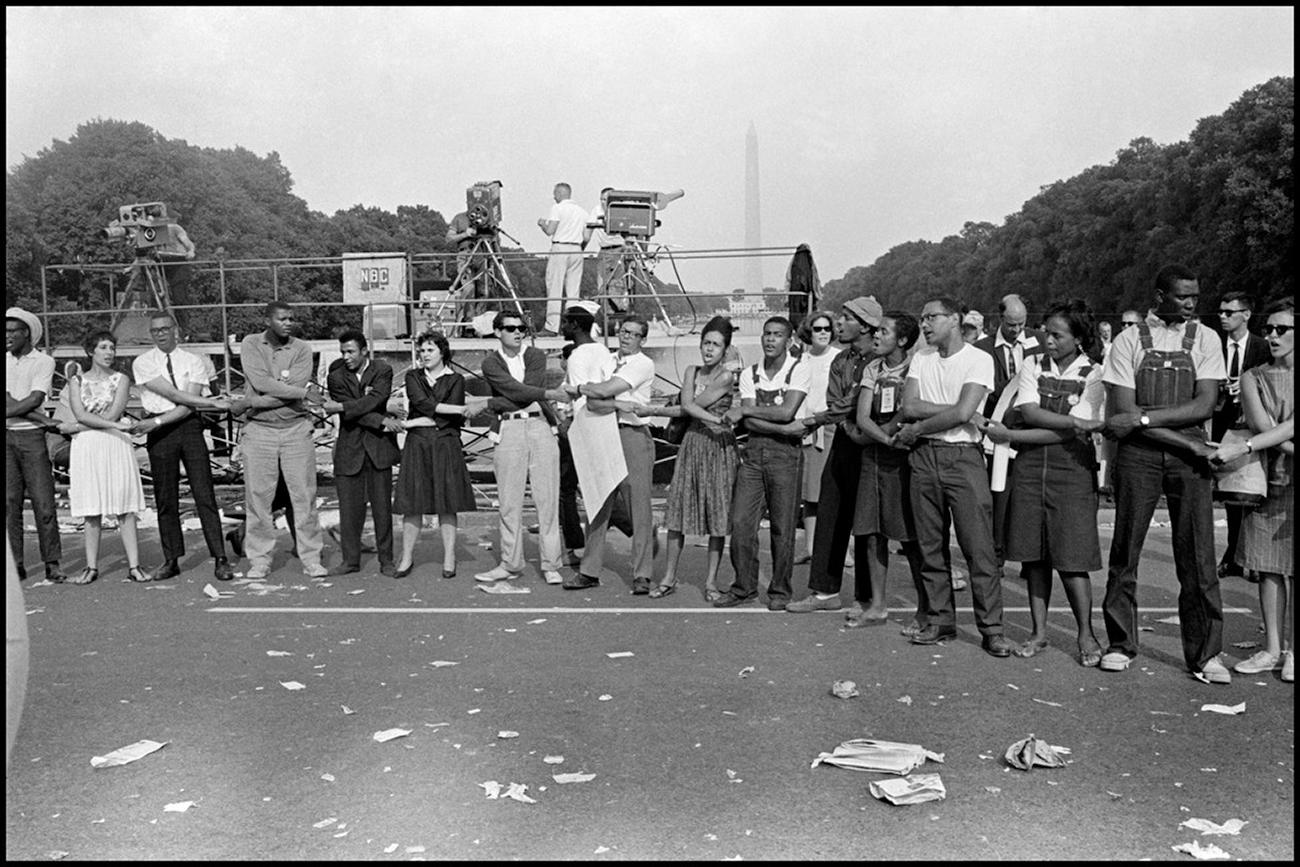

Government cooperation with protesters reached a new high in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom of 1963. President Kennedy’s administration not only tolerated the protest, but worked with organizers to create an event that would mobilize national support for Kennedy’s civil rights bill. The form the march took reflected a changed political environment. The goal was to affect public opinion through a concerted publicity campaign—“the first mass-marketed protest in the history of demonstrations in Washington,” Barber calls it—rather than appeal directly to members of Congress. Indeed, as Barber writes, Kennedy was wary of confrontation and, at a meeting with Martin Luther King Jr. and others, warned against creating “an atmosphere of intimidation.”

The compromise among civil rights leaders and the administration was very different from the kind of direct action that Dorie Ladner had undertaken in the South. Ladner, a Mississippi native, was drawn to the movement as a teenager by the 1955 murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till. Her first protest was in 1961 on behalf of the Tougaloo Nine, a group of college students who tried to integrate a public library in Jackson. Police responded with tear gas. In 1963, she protested at the funeral of civil rights leader Medgar Evers, whom she’d eaten dinner with the night he was murdered and who, Ladner said, had “raised [her] level of consciousness as it relates to social justice.” She got herself arrested on purpose at the funeral protest to avoid being bitten by police dogs.

After Evers’s funeral, Ladner went north, where she worked in the office of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in New York while the March on Washington was being planned. She shared her first day in Washington with a quarter of a million marchers, and stood next to King, overlooking the massive crowd while he gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. The steps of the Lincoln Memorial that day were, as she described them, the “world’s biggest stage.”

The march was broadcast live in the U.S. and in Europe, and attended by blacks and whites from every part of the nation. The marchers’ message was greater than any particular bill or demand. “We were hungry, thirsty for justice and equality,” Ladner said. “My people had been spat upon, abused, lynched, incarcerated, and exploited financially in the fields for generations, so when we came to Washington, that was coming for justice, to seek redress, to say that we’re tired.”

Panel participants and audience members also discussed the state of social movements and protest today and the challenges of organization and consciousness-raising in an ever more diffuse and fragmented society. To close, Ladner led the group in a rendition of the spiritual “This Little Light of Mine.”