“Where are you going?” my eight-year-old son asked the night before I left town.

“To Chicago,” I said, “to help my boss interview a philosopher.” It’s not my practice to avoid using hard words with my kids, but I wondered if he knew what a philosopher was.

“Wait,” he said, eyes lighting up. “Is his name Plato?”

Atta boy, I thought, he knows what a philosopher is. I needed to explain, of course, that Plato has been dead a really long time, but first I wanted to correct the unspoken assumption that the philosopher in question was necessarily a man.

“Her name,” I said, “is Martha C. Nussbaum.”

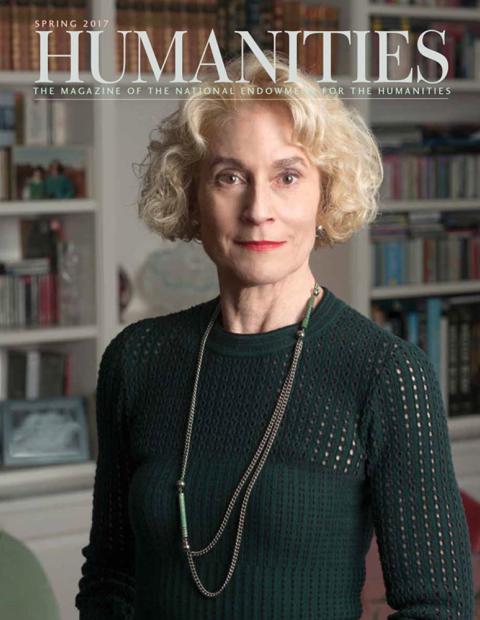

A professor in the law school at the University of Chicago, Martha C. Nussbaum is delivering the 2017 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities. She first entered the public consciousness as the author of The Fragility of Goodness and tightly argued essays in the New York Review of Books, where she took on Allan Bloom, and the New Republic, where she took on Judith Butler, Harvey Mansfield, and others. Eventually the author of more than 20 books, she has been profiled in the New York Times Sunday Magazineand, last year, the New Yorker. The former called her “a lawyer for humanity”; the latter, a “philosopher of feelings.”

She is both, actually, and much more: a classicist in ancient Greek and Roman literature; a feminist; an advocate for the equal rights of gays; a student of international development; a friend of India; a lover of literature; a singer, an actor, an athlete; a believer in the liberal arts; a liberal in the Rawlsian tradition; a thinker who writes about emotions such as disgust, anger, and vindictiveness that open wide onto pressing issues of law and politics. She is a political philosopher, not unlike Plato or perhaps the Stoics, with whom she more closely identifies, trying to identify the elements of a just society.

For this issue of Humanities, NEH Chairman William Adams interviewed Nussbaum, hitting upon several major themes of her career, and learning why she thinks the humanities are vital to democratic governance and citizenship.

Citizenship was also on the mind of Louis I. Kahn when this icon of modern architecture took up the subject of worker housing in a series of pamphlets he wrote in the 1940s—a subtly revealing episode in his professional development that NEH Public Scholar Wendy Lesser nicely captures in an excerpt from her new biography of Kahn, You Say to Brick.

Our writer William Funk followed archaeologist Becca Peixotto into the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia, now a National Wildlife Refuge but at one time a haven for escaped slaves who came to be called Maroons. Digging up traces of their survival has helped sketch a profoundly hardscrabble way of life, one so difficult that it must have seemed unbearable, unless slavery was the alternative.

And there is much more in this issue of HUMANITIES. A feature story about “telemedicine,” a once futuristic experiment in medical innovation, news about the state humanities councils, and an incredible object called an aquamanile.