It's 1903, and Sherlock Holmes, England's most famous consulting detective, retires at age forty-nine to become a beekeeper on his small farm on the Sussex Downs. Except for an adventure infiltrating a German spy ring and an investigation into the mysterious death of a teacher, nothing is known about the remainder of Holmes’s life.

That’s one version of the story, anyway. Try another: Holmes leaves London, raises bees, and at age sixty-seven marries twenty-one-year-old scholar Mary Russell, his intellectual equal and partner in solving new and quite dangerous mysteries.

Or how about this: An aging Holmes discovers the rejuvenating properties of bee-produced Royal Jelly, finally expiring on his one hundred third birthday, with the name “Irene” on his lips.

So many Holmeses, so many musings on a legend whose vast popularity often aroused resentment in his creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

That first scenario was written by Doyle, the author of fifty- six short stories and four novels that make up the complete and official Sherlock Holmes canon. The second is the basis of a highly engaging, ongoing series of books by writer Laurie R. King, and the third comes from the deeply moving Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, a 1962 “biography ” by noted Sherlockian scholar William Baring-Gould.

Despite Doyle’s lifelong ambivalence about his greatest literary success—which he felt detracted from his other writing—he imbued his late-Victorian hero with irresistible qualities that subsequently inspired hundreds if not thousands of other storytellers. Holmes lives in many dreams beyond Doyle’s, a startlingly malleable icon invented and reinvented in the hands of post-Doyle authors, filmmakers, actors, playwrights, television and radio producers, and more.

Some of these dreams can be found in innumerable pastiche fictions (new adventures for Holmes and his chronicler, Dr. John Watson); some are radical reworkings of the canon (the BBC’s popular, modern-day Sherlock); some offer a revisionist take on the old narrative (Michael Dibdin’s shocking The Last Sherlock Holmes Story); and some simply borrow, reverently, from Holmes’s legacy (Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, essentially another version of Doyle’s The Final Problem).

Doyle himself knew of alternative interpretations of Holmes, even telling stage actor William Gillette, who played Holmes for years, that Gillette could “murder [the character] or do anything you like to him.” Indeed, Doyle remained ambivalent and even peevish about Holmes, sounding quite dismissive about him and Watson in a short 1927 film that can still be seen on YouTube.

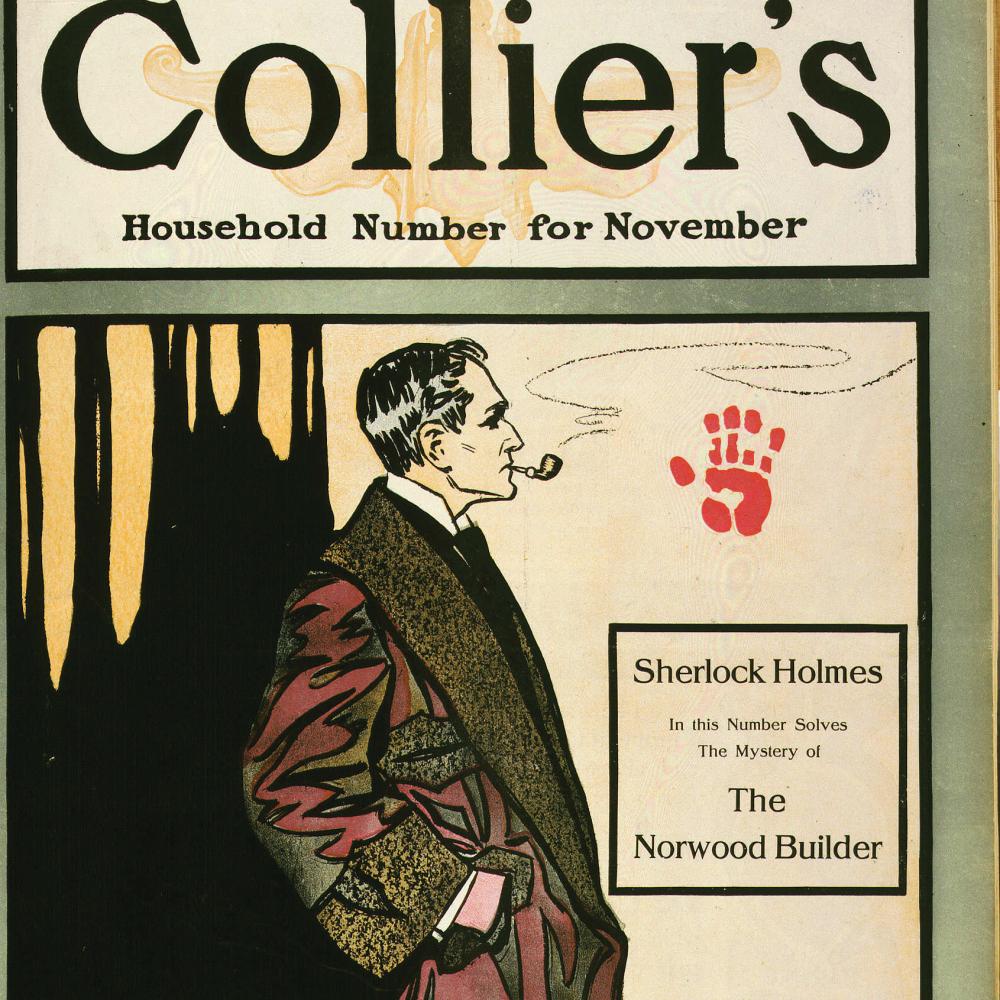

It was as a struggling doctor and writer that his A Study In Scarlet, introducing Holmes and Watson, was published in the 1886 Beeton’s Christmas Annual. The prolific Doyle then turned his attention to other literary pursuits he considered more serious. But an 1890 commission to write a second Holmes novel, The Sign of Four, sent the series off and running. Feeling the pressure of Holmes’s growing popularity, Doyle wrote a further twenty-four short stories within four years, drawing precious time away from the historical novels and other works of fiction he was simultaneously producing.

Doyle wrote fitfully about Holmes until 1927, finally declaring he was done for good. But he left behind an enigmatic sleuth who all but demands reinvention and rediscovery through the imaginations of others.

Why? Because Doyle kept Holmes removed from readers, wholly perceived and experienced (except in three stories) through the occasionally dubious accounts of Dr. Watson. Holmes is not so much a whole-cloth character as he is an aggregate of tantalizing details that inspire both comfort and curiosity.

It is the paradoxical appeal of Holmes—heroic but repellent, remote but indomitable, machine-like yet persuasively human—that causes him to linger in hearts and minds. The appeal is found in the psychologically complex performances of Holmes on television by Jeremy Brett and Benedict Cumber- batch, in works by authors Neil Gaiman and Anthony Horowitz, and in such cinematic gems as Jake Kasdan’s 1998 Zero Effect. Doyle might have been done with Holmes, but it’s clear that the rest of the world is not.