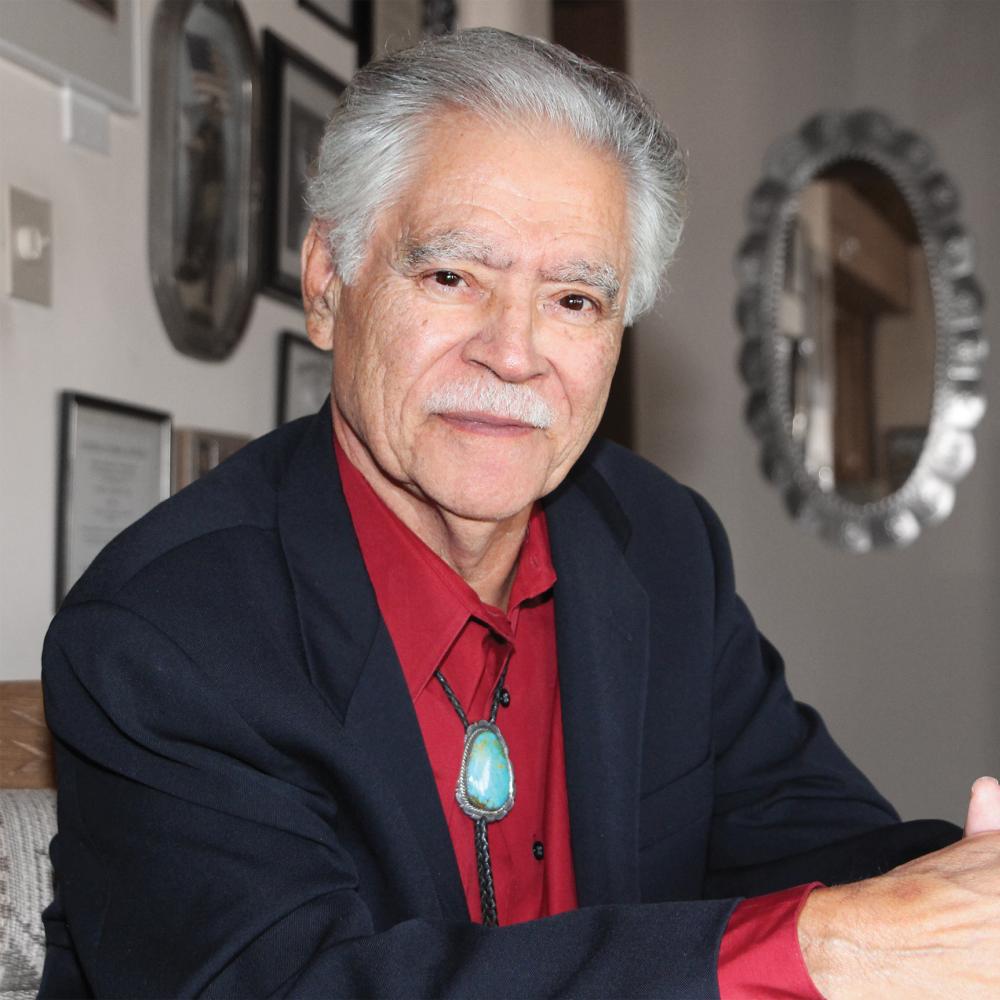

When Rudolfo Anaya won the Premio Quinto Sol in 1971, the prize was $1,000 and publication of his landmark novel, Bless Me, Ultima. This guaranteed the book would be in readers’ hands just as the Chicano Movement was taking root in the national consciousness. This community of Americans of Mexican descent was working hard to claim political agency and to affirm its unique cultural identity through the cultivation of art, theater, music, and literature that expressed the varied experiences of the Chicano people. Bless Me, Ultima, a novel about a young boy struggling with competing expectations and values in post-World War II New Mexico, resonated with Chicano readers, who gave it a place of prominence in the Chicano literary canon. Anaya was subsequently anointed the godfather of Chicano literature.

Bless Me, Ultima, however, appealed to wider audiences and has since become a best-selling title. Intriguingly, the novel is both a favorite of the educational curricula and, according to the American Library Association, one of the most challenged titles because of its treatment of religion and spirituality. Anaya has made peace with this complicated reception to his book. “I write what I was meant to write,” he says with conviction. “If anything, those attempts to censor my book mean that it’s going to be read. Ultima is unstoppable.” And indeed his beloved faith healer has enjoyed continued attention: In 2010 the book was selected for the NEA’s Big Read program, and in 2013 it was adapted for the screen. The character Ultima was portrayed by the legendary actress Míriam Colón.

With more than 40 books to date, Anaya too has had a remarkable journey. Born to a family of cattle ranchers and farmers in 1937 in the rural town of Pastura, New Mexico, he was destined, like Bless Me, Ultima’s child protagonist, to pursue an education. He and his late wife, Patricia, became literacy advocates, establishing educational scholarships for disadvantaged youth. Additionally, they founded a writer’s residency in their second home in Jemez Springs to support writers who “were not getting invited to those retreats back East. We had to help out any way we could.”

The success of Bless Me, Ultima was an auspicious beginning to Anaya’s long career. His next two novels, Heart of Aztlán (1976) and Tortuga (1979), complete the trilogy of narratives about young people at the crossroads of childhood innocence and the heartbreaking reality of adulthood. A series of story collections followed, but Anaya’s next breakthrough came with the publication in 1992 of Alburquerque, a mystery set in the city Anaya has called home since 1952. The novel’s protagonist, the troubled boxer Abrán González, navigates the parallel cultures of New Mexico—the contemporary capitalist arena and the traditionalist old world Nuevo Méjico—in order to discover his true identity and save the city. Arguably, this hometown hero and his ability to reconcile the spirituality of the past with an edgy modern era set the stage for aother of Anaya’s memorable characters, Sonny Baca.

The four Sonny Baca murder mysteries (Zia Summer, Rio Grande Fall, Shaman Winter, and Jemez Spring) highlight the New Mexican landscape and culture, giving particular detail to New Mexico’s unique festivities, foods, and folk beliefs, educating and entertaining readers about how this state became known as “The Land of Enchantment.” Anaya’s distinctive use of magical realism underscores the region’s rich imagery and mythology, honoring the legacy of its Native American, Spanish, and Mexican heritages. “These cultures have a very long history in the Southwest,” he says, “and it’s my responsibility to bring this knowledge to American literature.”

Anaya has continued to publish steadily. His most recent title is the novel The Sorrows of Young Alfonso, released earlier this year. “My imagination keeps sparking,” he explains. “Just when I think I’m done, another idea takes hold.” His body of work also includes six plays and no less than a dozen children’s books, including the perennial favorite The Farolitos of Christmas, which spins a touching tale around the New Mexican holiday essential, the paper lantern. “When children see themselves in books, the encounter makes them blossom,” he explains.

Among the many awards Anaya has received are two Governor’s Public Service Awards from the state of New Mexico, the American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation, a Kellogg Foundation fellowship, two NEA literature fellowships, and the NEA National Medal of Arts Lifetime Honor in 2001. Speaking to the honor of receiving the National Humanities Medal, Anaya becomes pensive: “I’ve been thinking a lot about what this recognition means, and I’ve decided it’s not just about me, it’s about New Mexico. We may be one of the poorest states in the union but have a wealth of beauty and culture. This award is about the people of New Mexico.”