One hundred seventy thousand years ago, our cave-dwelling ancestors ground up clay laced with iron oxide and covered their bodies, painted their walls, and encased their dead with the rich red of ochre. And over the thousands of years that followed, artists and shamans, merchants and manufacturers, and wild-eyed scientists and entrepreneurs have crushed red out of rock, squeezed it out of clay, pounded roots called madder, and finally ground dried insects known as kermes to create the color of luck, power, fertility, immortality, and invincibility. None were perfect, yet the world made do. That is until Hernán Cortés arrived in present-day Mexico in 1519.

Cortés, never one to miss a detail that might please his sponsors back in Madrid, noticed that the Aztec elite made use of a brilliant red that seemed even redder and deeper than the kermes that was used across most of Europe. Further investigation led him to “discover” a small insect, white and fluffy, which lived on the paddles of the prickly pear cactus, and when crushed produced an incomparable red. This bug was the cochineal.

New Mexico’s Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA) has launched an unprecedented exhibition—spanning two thousand years, four continents, and including nearly 130 objects from museums around the world—exploring cochineal’s rise in the sixteenth century, fall in the eighteenth, and surprising renaissance in the late twentieth century. To tell this story, MOIFA has not only borrowed and shipped. It has also pioneered new scientific techniques to discover and verify cochineal, sometimes in materials previously thought to contain none. Visitors to “The Red That Colored the World” thus get a front-row view not only of a fascinating history of a vastly under-appreciated source of red, but also to the intellectual and investigative prowess that sees red in the most unlikely of places.

The history of cochineal is a long one, but its beginnings are difficult to pinpoint. Because, unlike those dry cave walls and tombs of thousands of years ago, the particular circumstances of early cochineal use—a hot and humid climate and its frequent application to unsuitable fibers—mean that scholars have had to extrapolate from written or oral sources that purport to capture earlier practices.

It’s reasonably clear that cochineal was used on fabric in early Mesoamerica, but it was as likely to be painted on as it was to be applied as a dye. The problem, particularly in areas where it was most heavily cultivated, was that cochineal red doesn’t adhere particularly well on cotton or agave, which accounts for most of the early textile production in the region. In the Andes, however, where animal fibers were the norm, we have some pre-Columbian textiles that suggest ways in which cochineal may have been used elsewhere in the Americas. And that’s how the exhibition begins—with a shirt and loincloth from Peru, both dyed a deep, rich red, and dating from the 1100s to the 1300s. In and of itself, it is an amazing beginning.

Even ten years ago, very few objects anywhere in the world were known without a doubt to contain cochineal. Unless the creator had thought to make a note of the dye, no one was precisely sure what it actually contained. Getting beyond that required a new scientific approach and a whole new round of research. The research—some of it spearheaded by the museum and its curators—relies ultimately on high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Scientists and curators use HPLC to test tiny samples of materials suspected of containing cochineal. HPLC breaks apart individual chemical components in a sample and reveals something akin to a fingerprint. The possibility of finding a cochineal fingerprint changed the game, and made the exhibition possible.

And so, to supplement the early Peruvian textiles, there is also a small collection of ink-on-paper pre-Columbian Aztec administrative records. Cochineal red—we now know—shows up, as in a map of Mexico City, as a signifier of important places, important people, and important crops.

We also know from contemporary sources that Aztec women painted their teeth—and maybe their bodies—with cochineal. There were also probably some medicinal uses, although that is less clear. In any case, in almost all known instances, cochineal was treated as a luxury good. With the arrival of the Spanish, that didn’t change, but almost everything else did.

The Spanish were intensely interested in the economic possibilities of their territories, and after landing in the Americas in the late fifteenth century, sent forth explorers, artists, scientists, and bureaucrats to document and report. From this period, we have the Florentine Codex, a twelve-volume encyclopedia of the New World. In addition to providing the best snapshot of pre-Columbian cochineal use, the Codex also explores the place of the insect and its color in society.

The authors of the Codex tie it closely to the idea of blood and sacrifice in the founding myths of the Aztec. This association—one rooted deeply and widely in the Mesoamerican consciousness—was important not only for the existing economy and society that the Spaniards encountered in the sixteenth century, but was mirrored in the adoption of cochineal in Europe and elsewhere. Red had long been about power and glory, and cochineal made a red better than all others: It was brighter, richer, and more stable than its many alternatives.

This was not lost on the Spanish. Cochineal offered a way past the Venetian luxury textile market that had dominated the trade since the Middle Ages. By 1523 the Spaniards began to develop a cochineal industry to rival the Venetians’. At its height, the cochineal trade accounted for a significant portion of the Spanish empire’s economy; only New World silver was a larger export for Madrid. And, to harvest the bug, the Spaniards—at least initially—only had to adopt and extend the cochineal-based tribute systems the Aztec rulers had already put in place. Examples of tribute lists, from before and after the arrival of the Spanish, as well as a record—the Codex Huejotzingo—of a legal proceeding that deals with a cochineal-dyed rabbit pelt and a tribute dispute, help make the point that cochineal extraction for profit wasn’t anything new.

Maintaining what was essentially a monopoly, with cochineal by the ton—dried in such a manner that few in Europe could even tell whether it was animal, mineral, or vegetable—sailing into the harbors of Seville and Cádiz, the Spanish sold to just about everybody, but particularly the Italians, the Dutch, and the British. By 1570 or so, at least in Europe, cochineal was the only game in town if you happened to be making clothing for royalty, members of the Church, those that aspired to either, or if you were involved in the rapidly growing global trade in luxury goods. As an example, an Italian-made French cloak from the last part of the sixteenth-century—made from cochineal-dyed satin and embroidered and trimmed with silver and silk—would not look out of place on the shoulders of any well-dressed man about empire.

Cochineal red spread, and quickly. Britain, perhaps looking back to the Roman Empire, decided on cochineal to color its army’s uniforms. These red coats also harkened back to old Aztec uses of cochineal—demonstrating power and courage. Keeping that officer’s red coat company are silk stockings, embroidered shoes that would look at home on the previous pope, and a chair from Napoleon’s council chamber. Each gives a little insight into how broadly cochineal was used, and how it was incorporated into existing art forms.

For Barbara Anderson, the exhibition’s lead guest curator, this latter point is significant. “What’s really exciting,” she says, “is that we’ve been able to bring together art that isn’t visually connected, but that shares a common element nonetheless. It’s an unusual way to think about an art museum exhibition.”

Art, indeed. While scholars have long known about cochineal in textiles, HPLC is opening a whole new understanding of cochineal in European painting. Because of cochineal’s problems with cotton (or canvas), the traditional view has been that painters in Europe very rarely used it.

But, in fact, artists extracted the cochineal dye from textiles, not to use as a primary color (as had been assumed), but more commonly as a glaze—which gives a feeling of shimmering depth and texture to paintings. El Greco, as his painting The Savior demonstrates in the exhibition, worked with cochineal, as did, we now know, Titian, Tintoretto, and Rembrandt, among many others.

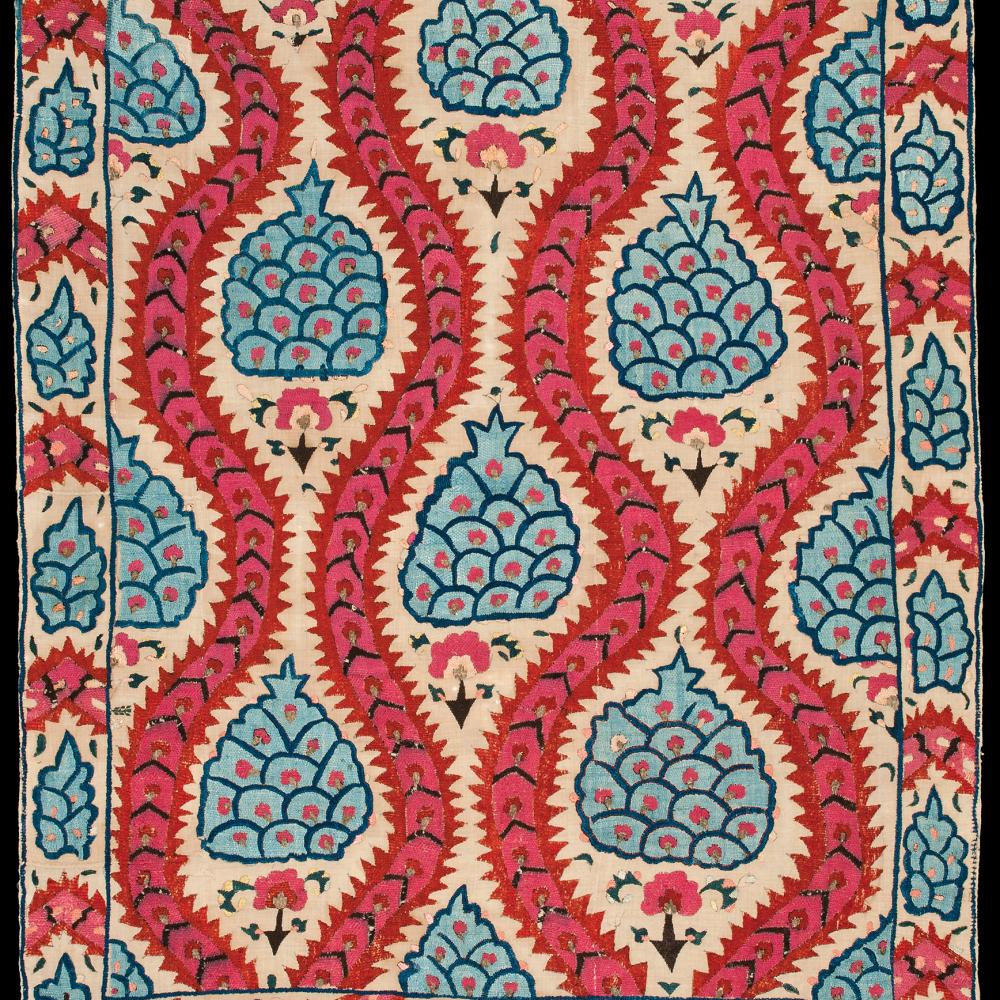

As might be expected, cochineal fever quickly spread globally. Spain made a wholehearted effort to set up a distribution hub in Japan as early as the last quarter of the sixteenth-century. But the Spanish were, along with all other Europeans except for the Dutch, tossed out in 1635. Thereafter, despite widespread use of alternative dyes, Dutch woolens with cochineal show up frequently in Japanese ceremonial and military contexts. The exhibition features a fireman’s ceremonial silk cloak and hood from Edo-period Japan (1603–1868). Both are scarlet red, with gold and silk thread waves and grappling hooks curling upward. Nearby are examples from Central Asia, Indonesia, Persia, and Uzbekistan. All are dyed with Spanish cochineal.

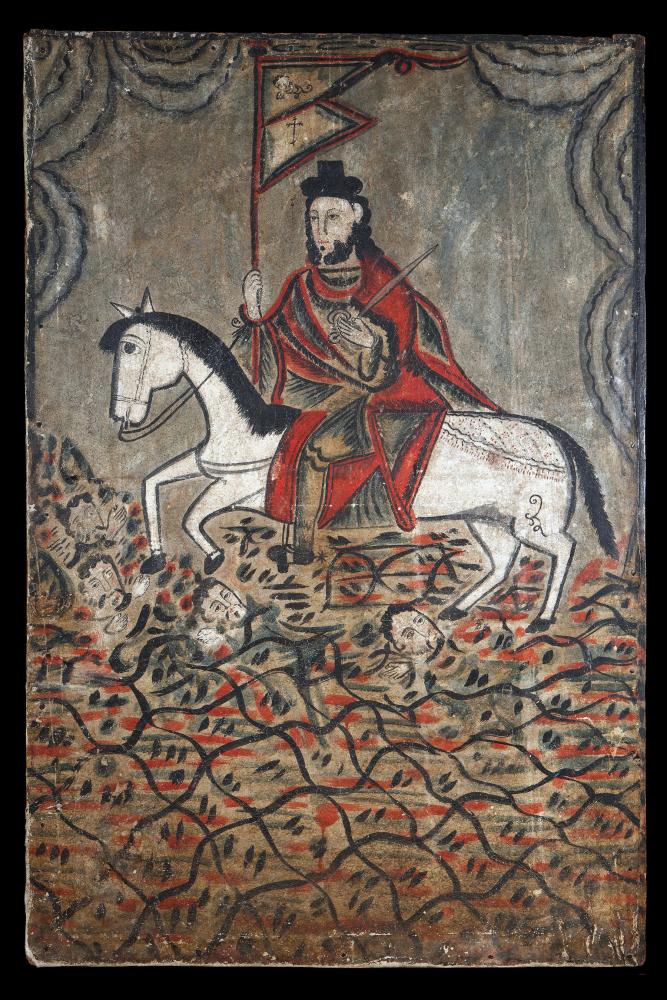

In the late sixteenth century, the cochineal trade was essentially one-way: Mesoamerica (and Oaxaca specifically) to the rest of the world. But within a hundred and fifty or so years, cochineal-colored products from abroad as well as those produced in the New World began showing up in the cochineal homelands. Two paintings, both from South America depicting saints and dating to the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, show evidence of cochineal. But it is farther north, in the heart of the Spanish cochineal industry, that the red was most frequently reintegrated into artistic production.

Luxury, of course, continued to play a role in Spanish America. A lacquer container for writing instruments and paper known as a papelera, on loan from the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City, is as ornate as any Baroque creation, with cochineal visible in and amongst the Roman-inspired vignettes of country life, sweeping vines and flowers, and mythological creatures. Not nearly as complex or well made—but clearly aspirational—is a writing chest (escritorio), probably also from Michoacán, which mimics the luxury of the papelera through the liberal use of cochineal.

Cochineal spread even farther north, with Spanish New Mexicans using it for religious art—the paintings of saints and the Virgin Mother known as retablos, and the small statues of sacred subjects known as bultos being most frequent. And with the move north, cochineal entered into other artistic repertoires as well.

For instance, the first documented use of cochineal among the native peoples of North America was in the Navajo lands of the 1790s. Beginning in the late sixteenth-century, cochineal-dyed woolens—rugs, clothing, and tapestries—were starting to come back into what would become the American Southwest. By the third decade of the 1800s, European wool was found not only up and down El Camino Real (where it had been since the early 1600s) but also along the Santa Fe Trail.

These woolens were traded, unraveled, and the cochineal-dyed yarn distributed. Much of this yarn was then rewoven in Pueblo, Navajo, and Hispanic textiles. A Vallero Star blanket from the Museum’s own collection made of red Saxony wool and dyed with unadulterated cochineal, and dating to the mid nineteenth century, is a superb example. Nearby is a Navajo sarape, from the same period, with mill-woven European yarn and pure cochineal dye.

Farther north, the Plains Indians—particularly the Lakota—made use of ready-made cochineal-dyed woolen cloth for ceremonial purposes, as in a headdress incorporating the dyed fabric into an eagle and turkey feather-adorned trailer. There too, it spread beyond the purely ceremonial and ended up in leggings, horse gear, and blankets—one on loan from the Denver Art Museum, probably from the 1800s, designed by a young man to woo his love.

By the mid 1800s, cochineal was falling out of favor, helped along by the Mexican War of Independence. Synthetic dyes—made mostly by those countries that had tried and failed to replicate the cochineal industry—then came into their own and offered a cheaper and more reliable red. Synthetics soon took over not only the textile industry but other industries as well. Cosmetics and food adopted the synthetics to color their products, and cochineal was nearly forgotten.

Two forces, however, have reinvigorated the use of the small bug, which is now primarily ranched in Peru. The first is renewed interest in local and national traditions. The second is a swelling interest in the use of organic and natural materials in food and clothing, although in 2012 a brouhaha erupted among vegetarians and vegans over the use of cochineal in Starbucks’ strawberry Frappucinos.

Just before visitors step back outside into the bright blues and browns and greens of a New Mexico high desert summer, Anderson’s enthusiasm for what MOIFA has put together seems completely justified in the face of the final piece in the exhibition. It is a 2014 haute couture dress from the Navajo designer Orlando Dugi, and it is a masterwork—hand-dyed with cochineal and hand-stitched—scarlet and striking. It also captures the connection that is at the heart of the entire show. It draws the mind back to that sixteenth-century Frenchman’s cloak. An Italian renaissance courturier and a twenty-first-century Navajo dressmaker united by a bit of white fluff on a cactus—a testament to cochineal’s conquest of the world.