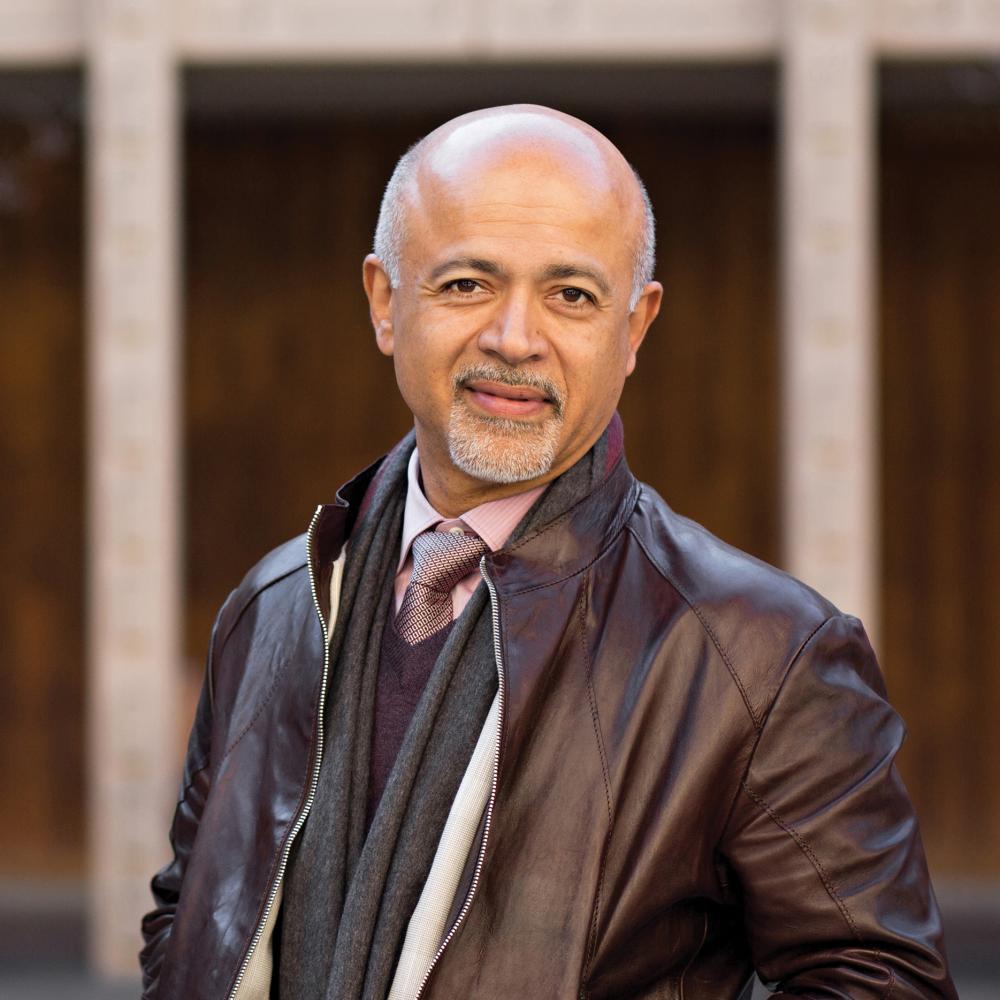

Abraham Verghese wonders why we make such a singular distinction for physician-writers. We don’t make quite as much of it when writers come from other professions, he points out. And for Verghese, there is not a pronounced separation between his work as a physician and his work as a writer. Medicine, he says, is his “first great love,” and his writing has come directly out of that.

Verghese was born in Addis Ababa to expatriate Indian parents. He began medical school in Ethiopia, but his studies were interrupted by the civil war in 1974. By that time his parents had relocated to New Jersey and he joined them there. He became a hospital orderly because he was unable to attend medical school in the United States without first going back to get his bachelor’s degree. “At the time, it certainly didn’t seem these were good things—in fact, these were all terrible things,” he says of that tumultuous period in his life. But this nontraditional beginning led to Verghese’s brilliant career as both a physician and an author.

As an orderly, he was inspired to go back to medical school, and did so in India, where he brought a renewed passion to his schooling and got “wonderful training.” He learned to appreciate the art of the physical exam from his favorite professor—percussing a lung before X-raying the chest, for example, or noting the particular odors given off by a sick patient. He returned to the U.S. for his medical residency at a hospital in Johnson City, Tennessee. And then, after moving once again to complete a fellowship in infectious diseases at Boston City Hospital, Verghese chose to return to Johnson City to settle. It was the mid 1980s and he felt that in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains he’d at last found a permanent home for himself and his family.

The AIDS epidemic had taken hold of America’s cities, but it didn’t seem like something that would affect a place like Johnson City. When the epidemic began surfacing in this rural area, Verghese became the local expert. There was little he could do for his patients, mostly gay men who were stigmatized for having the disease. But he aimed to help them die with dignity and whatever comfort possible. Now famous for his presence at the bedside, he expressed supreme empathy and respect for these patients, nearly all of whom faced certain and premature death.

He wrote of this experience in his first book, My Own Country, published in 1994 to critical acclaim. He had become increasingly interested in writing, and took a break from medicine to attend the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He graduated in 1991 and then returned to medicine, taking a position as professor and chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Texas Tech Health Sciences Center in El Paso, Texas.

“In every place I’ve lived, I’ve felt as much at home as I can ever feel, but perhaps never more so than in El Paso,” he says, a place where “the prevailing skin color was such that I became unnoticeable. [My skin color] was not something I had ever given much thought to . . . but the beautiful thing about Texas was that I could disappear in America.”

As a writer, he believes that this outsider’s sense can be a strategic advantage, because “you are less susceptible to some of the clichés of observation you don’t even know you’re making. Since you’re naïve, you can make an observation that’s fresh.”

Verghese, who is now the Linda R. Meier and Joan F. Lane Provostial Professor Vice Chair for the Theory and Practice of Medicine at the Stanford School of Medicine, went on to write more books. Another memoir, The Tennis Partner, is about his friendship with a medical resident and recovering addict. His novel, Cutting for Stone, stayed on the New York Times list of best-sellers for more than two years.

The art of paying attention runs, like a theme, through Verghese’s medicine and writing. He is best known in the medical community for “being able to read the body as text.” At the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he learned that “‘God is in the details,’” and this, he says, is true both in writing and in medicine. As a TED speaker, he has argued for the importance of the physical exam in this age of advanced tests and scans. At Stanford, he teaches students at patients’ bedsides instead of around a table. He believes that the “burden on the physician-writer is to go beyond just describing—and to find meaning” in the “extraordinary, intimate moments in the lives of others” that physicians so often witness.