In 1939 in Baltimore, a unique collaboration occurred between the chemistry department of Johns Hopkins University and the dance program at the Peabody Institute. From the atomic makeup of the compound benzene (C6H6) came the inspiration and structure for Carol Lynn’s choreography in The Chemical Ballet, performed just once, at the annual meeting of the American Chemical Society. The event made it into the pages of Life magazine, which described the dancers’ movements as they represented hydrogen and carbon atoms disturbed by oxygen, fire, and finally an atom-smasher: “Neutrons leap out, fly among the atoms, breaking up the molecular formations, and reduce them to a seething chaotic mess.”

Film of the performance was deteriorating among dozens of canisters in the Peabody archives when, in 2010, dance faculty member and centennial programming director Lisa Green-Cudek started hunting for old material. The labeling was nondescript and it was anybody’s guess which of the films were worth preserving. Eventually, the Peabody, which since 1986 has been part of Johns Hopkins University, conserved five films, excerpts of which have been looped together and are being shown as part of “Moving History/History Moving: Stepping through 100 Years of Peabody Dance.” Curated by Green-Cudek, the exhibition combines film, artifacts, books, and photographs to tell the story of a dance school that has long collaborated with musicians, artists, and historians, while engaging in cutting-edge dance forms. With a grant from the Maryland Humanities Council, a version of the exhibition travels the state during the rest of this year, accompanied by talks and performances. A conference for dance historians was held in March.

Philanthropist George Peabody established the Peabody Institute in 1857 in Baltimore as a prestigious conservatory to train musicians and singers for the higher echelons of the performing arts, producing over the years such notable alumni as composer Dominick Argento, pianist André Watts, and the singer-songwriter Tori Amos. Certainly dance was not part of Peabody’s vision. In fact, when the Peabody first offered dance classes in 1914, the school didn’t even call it dance. The course was in eurhythmics, a form of instruction developed by Swiss musician Émile Jaques-Dalcroze to teach rhythm to music students through movement. Dalcroze’s methods would influence modern dance pioneers such as Hanya Holm, Rudolph Laban, Marie Rambert, and Uday Shankar. Ballet Russe’s shocking Rite of Spring, which caused rioting in the streets of Paris for its primitive, unballetic movement, was based on Dalcroze techniques. Dalcroze settled his school in the utopian community of Hellerau, Germany, and in 1913 produced Gluck’s opera Orpheus and Eurydice in a spectacle that combined Adolph Appia’s modern theater with Dalcroze-trained musicians, singers, and dancers.

Dance as dance officially started at the Peabody in 1916, when the school brought Gertrude Colburn to lead the program, adding ballet training—one of the few outposts in the United States outside of New York to have such a thing—and barefoot aesthetic dancing in the mode of Isadora Duncan, the mother of modern dance. By 1922, Peabody dancers were staging their own over-the-top production of Dalcroze’s Orpheus and Eurydice, with a cast of two hundred musicians and dancers, charging the extravagant price of one dollar per ticket (a movie cost seven cents). Support for dance at the Peabody also came from railroad heiress and amateur dancer Alice Warder Garrett. In the early twenties, Warder Garrett hosted the Russian avant-garde designer Leon Bakst to transform her Baltimore mansion, Evergreen—specifically adding a theater with a small stage where she could take ballet class every morning.For years, Warder Garrett would invite Peabody dancers to practice their barefoot repertoire on the grounds of the estate and perform in her theater, the only theater in the world designed by Bakst.

Colburn laid the foundation for integrative dance at Peabody, training Lillian Moore, who went on to dance with Balanchine and become one of the first dance historians in the United States. Colburn brought onto the modern dance faculty Bessie Evans, who researched extensively with Native Americans across the country in order to publish American Indian Dance Steps in 1931, with her sister May. The book is still considered the authoritative manuscript on Native American Dance, offering step-by-step instruction on how to recreate the dances. “If you go to Amazon and type in Native American dance, this is the first one that comes up,” says Green-Cudek. The Evans sisters were part of a new interest in historical and world dance sweeping through the American dance community, spearheaded by the Denishawn dance company, a short-lived but influential partnership between dancers Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis. At their Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts in New York, the curriculum included Egyptian, Greek, Japanese, Aztec, and classical Indian dance among others.

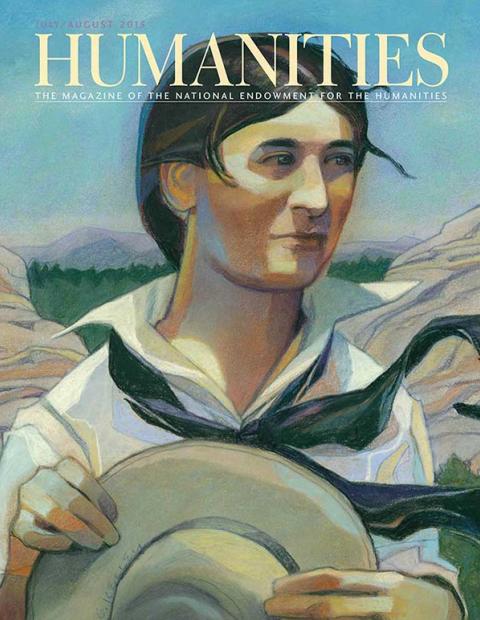

Carol Lynn, who would lead Peabody Dance from 1947 to 1970, was a protégée of Shawn, attending his academy and cutting her teeth in the 1930s as administrative director of his creative retreat in the Berkshires, Jacob’s Pillow. It was Lynn who convinced Shawn to allow women to come and dance at Jacob’s Pillow, and she became an innovator there in the art of filming dance. Lynn knew everyone through Jacob’s Pillow, evident in the numerous photographs of dance greats signed to Lynn: Alexandra Danilova, Anna Pavlova, Martha Graham (before she was the Martha Graham and appeared as just another Denishawn dancer in exotic costume), Doris Humphrey, José Limón, and, of course, Shawn himself, shown in a photo exerting an iconic modern reach. Through her connections, Lynn brought the leaders in American dance to her students in Baltimore.

In a way, the current crop of Peabody dancers enrolled in the preparatory school are descendants of the Denishawn movement. Dancers trained by Lynn often came back to teach, and in turn another generation would study, leave to have their own careers, and return to teach. The latest collaboration is with Clay Taliaferro, a former principal with the José Limón Dance Company (founded by Limón and Denishawn dancer Doris Humphrey), who subsequently took on the roles danced by Limón and now is charged with reconstructing Limón’s original works around the world. Taliaferro worked this past year with boys who attend Peabody Dance on full scholarship. He set a new piece of choreography on nine of them that is an homage to the influential male modern dancers of the twentieth century. The boys will be performing this dance in conjunction with the traveling exhibition and living-history presentations. And if you are lucky enough to see the performance, you will notice them doing the same movement—falling sideways, off-balance but amazingly suspended by the reaching arms—captured in that memorable photograph of Ted Shawn.