The current revival of the ballet-based musical On the Town, directed by John Rando and now playing at the Lyric Theatre in New York City, offers an opportunity to revisit the intricate, enveloping music and lavish dance numbers that characterized Broadway shows from the Golden Era of musical theater.

The production features a twenty-eight-piece orchestra and uses the original orchestration, which is a pleasure to experience. The sound is full, and the highly expert players deliver the score with aplomb. Equally compelling is the choreography by Joshua Bergasse: It brilliantly pays respects to the show’s history while bringing a contemporary flair all its own. One major aspect of the original production—an attention to the racial politics of casting—is not replicated in the revival.

Broadway musicals have dealt with race and ethnicity in a range of ways. There have been musicals that confront the problem directly—think of the images of southern black labor in Show Boat (1927) or the gang conflict in West Side Story (1957). Extensive song and dances segments were central to delivering the plots of many such musicals, with Agnes de Mille and Jerome Robbins as the leading choreographers. But questions of race and casting—selecting the real people who inspired these stories, songs, and dances—remained fraught. White performers dominated, and performers of color played racialized characters who were often segregated on stage and asked to enact longstanding stereotypes inherited from blackface minstrelsy.

In the original production, On the Town presented an early exception to this norm. Including a mixed-race dance chorus and starring a Japanese-American ballet dancer named Sono Osato, it debuted on December 28, 1944, just as the Axis was beginning to collapse in the final struggles of World War II. This staging not only marked the debut of a dazzling group of young creative artists—the composer Leonard Bernstein, the lyricists Betty Comden and Adolph Green, and the choreographer Jerome Robbins—but it also challenged racial performance practices of the day.

In historical chronicles of Broadway musicals, casting receives much less attention than, for example, composition or lyrics do. In the inaugural version of On the Town, race and ethnicity were treated carefully. African Americans were dispersed on stage in an effort to represent a mixed-race citizenry. Black sailors and soldiers stood on stage alongside their white counterparts, and mixed-race couples joyously danced together—all in the midst of World War II, when the real American military was contentiously segregated and the government operated racial internment camps.

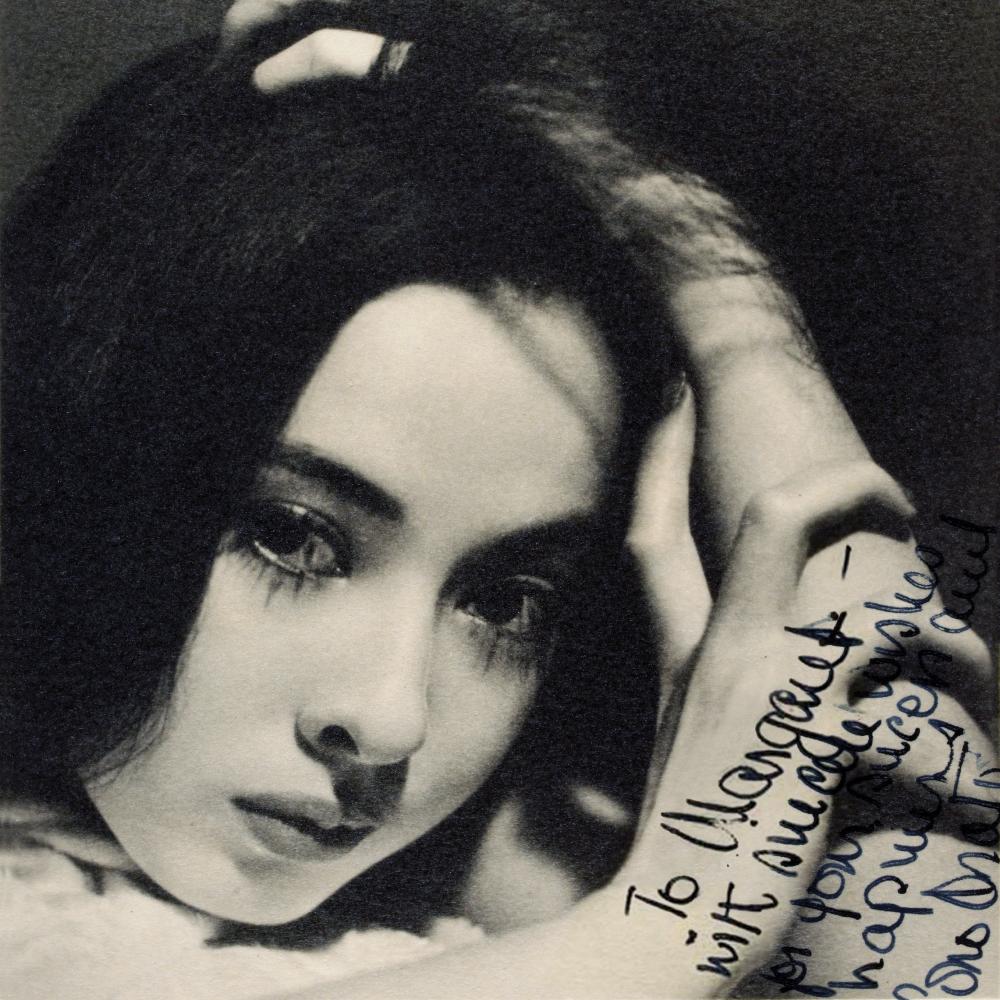

Featuring Sono Osato as the lead character “Ivy Smith” marked another major step in challenging segregated performance practices of the day. Osato had substantial professional experience in the world of ballet, bringing a high-class pedigree to On the Town’s aspirations as a “ballet musical.” At the same time, she was nikkei—that is, part of the Japanese diaspora. Three years earlier, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, her father had been arrested as an “alien enemy,” becoming one of some 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry who were interned.

On the Town debuted in an era when war suspicion of Japanese living in the United States was intense and systematic. Asian immigrants in the United States had limited legal status, and Asian performers had virtually no access to work on Broadway or in Hollywood. As a result, casting an actress of any Asian background stood out mightily in the context of Broadway, where the last Asian female in a featured role had probably been the Chinese-American Anna May Wong in 1930.

Sono Osato’s appearance in On the Town represented both a notable moment in the racial history of the American musical and a substantial risk for the creative and production team of the show. In other words, this work of commercial theater carried a political message that was performed but not otherwise articulated.

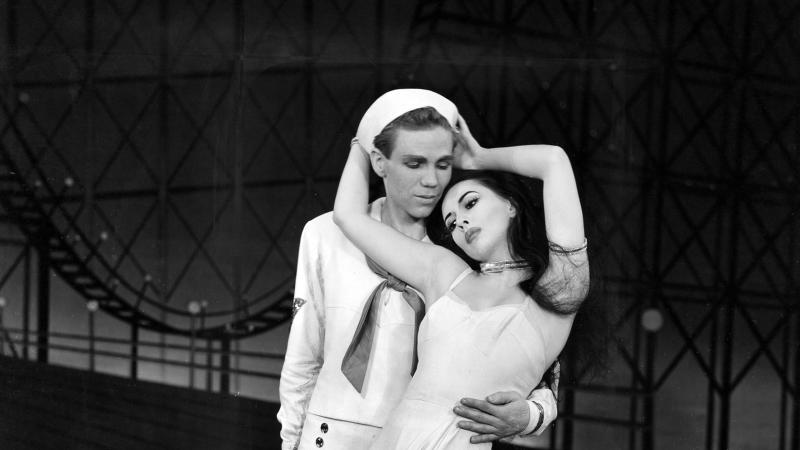

The plot of On the Town features three sailors on a one-day leave in New York City during World War II. Near the opening, the sailors sing the now-iconic “New York, New York.” Each of them pursues a girl during the course of the show, although more often the women do the chasing, delivering raunchy comic numbers like “Come Up to My Place” and “I Can Cook Too.” Near the end, the beautiful ballad “Some Other Time” punctures the hilarity with a sober reminder that war can shatter daily life and human relationships.

Central to the plot is the pursuit of Ivy Smith by Gabey, one of the sailors. Ivy has just been selected as “Miss Turnstiles” for the month—a beauty queen of the subway—and Gabey falls in love with her image on a poster inside a subway train. Sono Osato, playing the role of Ivy, made her first appearance in Scene 4 of the show, titled “The Presentation of Miss Turnstiles,” and her race was adroitly managed from the outset. A spotlight shone on Ivy Smith, who pantomimed her surprise at being chosen, and an M.C. sang a description of the newly chosen pageant queen, affirming her patriotic qualities and presenting her as a puzzling bundle of paradoxes:

She’s a home-loving girl,

But she loves high society’s whirl.

She adores the Army, the Navy as well,

At poetry and polo she’s swell.

Male admirers then “do a satiric dance,” as the script puts it, intended to be “based on the contradictory attributes that Miss Turnstiles seems to possess.”

Thus, the character of Ivy was introduced with a series of one-liners, which presented her as a “contradictory” figure, filled with surprises. Comedy did not traditionally go hand-in-hand with female glamour and sexual allure, and Japanese-American women did not become beauty queens in wartime America. Casting Osato as the lead in On the Townmeant that Gabey was not only headed for a fling but that he was flirting with miscegenation, which remained illegal in many states during the 1940s. Even more scandalously, in the midst of an all-out war, Gabey was pursuing a gal with a familial connection to the enemy.

The audacity of the decision to hire Sono Osato for the inaugural production of On the Town gains clarity within the context of her family’s story. Sono’s father Shoji was an immigrant from Akita, Japan, who came to the United States at nineteen. He picked strawberries in California and later began developing skills as a photographer, settling in Omaha and working for a local newspaper. Meanwhile, her mother Frances Fitzpatrick was of Irish and French-Canadian descent. Frances and Shoji met in Omaha and “fell in love on the spot,” according to Distant Dances, Sono’s autobiography. Because of anti-miscegenation laws in Nebraska, they went to Iowa to be married.

In 1925, the Osatos moved to Chicago, where Frances’s family was based, and in 1934—at age fourteen—Sono auditioned for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, which was on tour in the United States. She was hired immediately. Thus Sono as a teenager was suddenly working with first-class professionals in a troupe of Russians who had gone into exile during the Revolution.

In 1936, Frances and Shoji gained attention in the Chicago press for opening a traditional Japanese tea garden in a bamboo building that had been constructed by the government of Japan three years earlier for the Chicago World’s Fair. The tea garden was intended to “promote amicable relations between Japan and America,” as the Chicago Tribune reported. The Osatos kept the business open until the end of the decade, which turned out to be an unfortunate decision. Japan invaded China in 1937 and continued a violent occupation there while preparing for a wider sphere of conquests.

Sono’s career with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo lasted from 1934 to 1940, during which she grew artistically and became adept at crossing cultural boundaries, as her family had always done. When she left the Ballet Russe, she began stepping forward as an independent performer. A promotional letter on her behalf, written by a publicist in 1940 and now housed at the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, provides an intriguing view of how Sono was being marketed as a transnational artist. At this point—one year before Pearl Harbor—her mixed-race heritage was pitched as a valuable asset. Sono was described as “a cultural League of Nations”—as being as “exotic in real life . . . as the Siren in The Prodigal Son” (Le fils prodigue is a well-known ballet). At the same time, her “Chicago English and brisk American manner” were “as exhilarating as football weather.” Sono was thus promoted as a cosmopolitan figure whose identity was thoroughly hybrid.

Immediately after Sono left the Ballet Russe, she began dancing with Ballet Theatre, which was a relatively new American troupe and included the young Jerome Robbins. In the months after Pearl Harbor, the same “half-Japanese” heritage that produced rhapsodic exclamations about Sono’s “exotic beauty” led to trouble when Ballet Theatre went on tour. She was prohibited from entering the state of California, and she was denied a passport to travel with the company to Mexico.

Shoji Osato faced consequences more severe than his daughter’s. His arrest by the FBI one day after the assault on Pearl Harbor had stemmed from his ties to Japan and his management of the tea garden. According to historian Mae M. Ngai, 2,192 Japanese were arrested in the United States immediately after the Japanese attack, putting Shoji in an unfortunate but select group. Government documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act show that Shoji was not involved in any nefarious or subversive activities. Like any immigrant, he bridged cultures, both economically and personally. Shoji ended up being held at a facility on the South Side of Chicago for nearly six months, then released on a protracted parole, during which he was prohibited from leaving the city.

Throughout this period, his daughter enjoyed improbable-seeming success, as she continued to dance with Ballet Theatre and then moved to Broadway. In the fall of 1943, she joined the cast of Kurt Weill’s One Touch of Venus, with choreography by Agnes de Mille and Mary Martin as the star. Sono’s role was that of “Premiere Dancer,” which brought rave reviews. One New York newspaper reported that Sono “stopped the show on opening night and has all but stolen it ever since.”

While Osato’s mixed-race heritage had inhibited her capacity to tour with Ballet Theatre, it did not seem to concern Broadway producers. Acknowledgment of her race, however, went underground for a time. Her next Broadway role came with On the Town, and the show’s creative team clearly worked to manage Osato’s race as they shaped the show. The role of Miss Turnstiles was written expressly for her, as numerous sources document, and all this occurred within the context of a show that was drafted and cast very quickly.

As it turned out, by late December 1944, when the premiere of On the Town took place, the Allies had begun gaining traction in the war, and Sono’s prominent presence on stage was probably less volatile than just a few months earlier, when casting decisions were made. Iwo Jima had been bombarded in November 1944, a prelude to the Allied invasion of the island that would take place the following February. Perhaps most relevant for Sono, the internment of Japanese Americans on home soil had been coming under sharp criticism, and on December 17, 1944, the War Department announced that the “mass exclusion of persons of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast was ended . . . effective January 2,” as quoted in the New York Times. It took some months to implement that policy.

Shoji Osato still remained on parole in Chicago, but he kept petitioning to join his wife and children in New York City, where they had settled. His requests were repeatedly denied. This meant he was not present for his daughter’s opening night in On the Town. He finally attended the show in April 1945.

Sono Osato’s presence as the star of On the Town, playing the unlikely role of an all-American beauty queen, represents one of the more remarkable moments on Broadway during World War II. As a woman of Japanese-American heritage, she soared past historic barriers for performers of her race, and she did so with such flair that the barriers almost seemed to be an illusion. But not quite. Her prodigious talent and intelligence, together with her beauty and work ethic, trumped the social and racial constraints that surrounded her. Sono’s work with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo put her in New York City at an historical moment when the realms of dance and theater had become deeply cosmopolitan, in large part from absorbing so many European refugees. Coming of age with the Ballet Russe also put Sono in a profession dedicated to enacting fantasies. Exoticism represented a norm in ballet, and the transnational migrations of the Ballet Russe provided a fluid environment in which her stage persona could be in a state of constant flux. She played sirens and swans, lovers and Japanese bar-boys, and, with One Touch of Venus, she started traversing genre boundaries, swapping tutus for short velveteen skirts.

Then she became Miss Turnstiles. Sono brought to On the Town all of her professional experience in the ballet, making it possible for the creative team to realize its vision of building a musical out of dance. Casting her as a beauty queen issued a direct challenge to social norms, setting up a scenario in which audiences saw a Japanese-American woman taking a role onstage that was off-limits to her in real life. Osato’s presence sharpened the show’s politics, constructing a cast that boldly represented the diversity of the United States.

For On the Town’s revival in 2014, wartime issues no longer have currency. Rather, its producers have focused on giving new life to a gorgeous work of art, and they have succeeded magnificently in that realm. Once again, an experienced ballerina is the star: Megan Fairchild, who is a principal dancer with the New York City Ballet. She is a brilliant dancer, yet she does not have an Asian-American heritage. The cast includes some African Americans—notably Phillip Boykin, who is lead singer in the opening number, “I Feel Like I’m Not Out of Bed Yet.” He also plays the master of ceremonies, a role that recurs in shifting guises throughout the show.

Since the 1940s, quantum leaps have been made in casting people of color and paying attention to issues of racial representation. At the same time, equal inclusion is still far from standard practice, and racialized roles have not disappeared. It’s a mixed bag. Perhaps most fundamentally, On the Town raises intriguing questions about the obligation of a revival to replicate racial decisions from the original production, and the answers to these questions are likely to shift with an ever-evolving racial climate. In the case of On the Town’s newest iteration, the production team has opted to chart its own path, separate from the casting choices that sent an important message at the show’s inception.