At first glance, “One Hundred Years of Flamenco in New York” appears relatively modest—a single room of photographs, films, documents, and costumes—but the world contained within these four walls is dense, both with stories and interconnections.

Presented at the downstairs Vincent Astor Gallery of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and curated by the flamenco experts K. Meira Goldberg and Ninotchka Bennahum, this turns out to be the first retrospective tracing the evolution of Spanish dance in the city. Its contents, and the accompanying program of flamenco films, are drawn from the library’s extensive dance holdings as well as various private collections. Supported by the New York Council for the Humanities, the show is a joint venture of the library and Carlota Santana, a New York-based teacher and company director, who is the doyenne of New York flamenco.

What emerges is a vivid, often surprising, account of the continuous presence of Spanish dance, in its various forms: authentic, fanciful, exotique, or fused with dances as disparate as tango and ragtime. The dramatis personae includes the Viennese ballerina Fanny Elssler, famous for her cachuca, which she brought over in 1840; the Catalan gypsy—a real spitfire—Carmen Amaya, who shook up the scene when she relocated here after the Spanish Civil War; and on to the strikingly handsome, Brooklyn-raised José Greco and others: Martin Santángelo, Soledad Barrio, Leilah Broukhim, and Nélida Tirado.

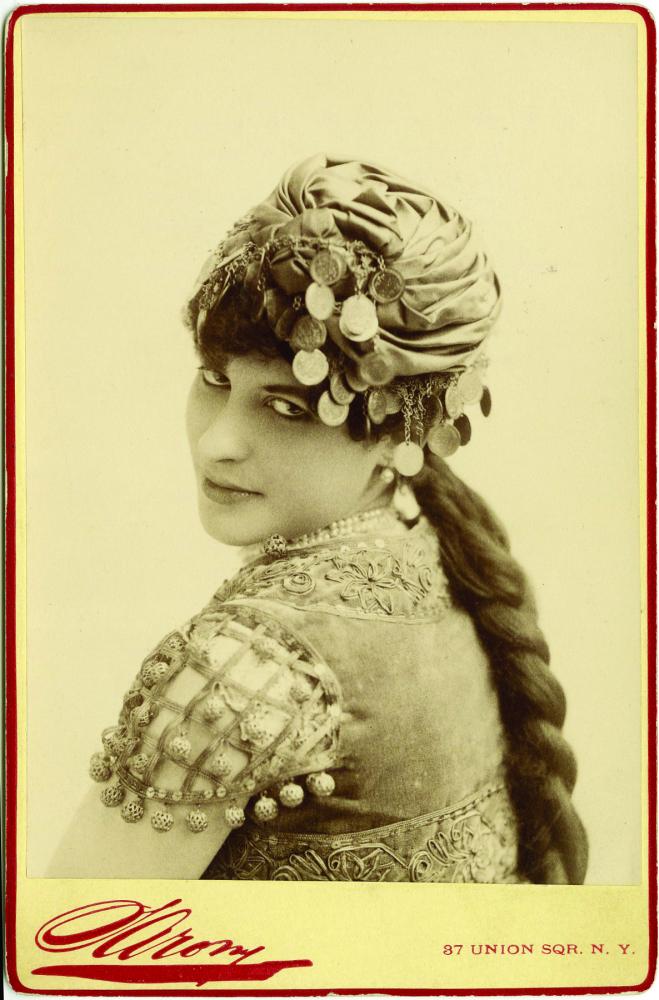

By the turn of the past century, Spanish dance had come to symbolize the exotic, modern, and outré. Visits by performers like La Cuenca and Carmencita fanned the fashion for all things Iberian. American women had their portraits taken holding fans, wearing mantones (fringed shawls) and giant earrings. The curving lines and powerful, earthy movements of flamenco and the classicized folk dance bolero suggested a kind of freedom from convention and sensual abandon. A sketch by Nestor de la Torre of the dancer La Argentina, friend of Federico García Lorca and choreographer of note, depicts her as a seductive creature with a sinuous back and languorous curves. In the forties, the French artist Jean Cocteau wrote of the gypsy performer Carmen Amaya that “not since Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes have we been able to experience this kind of lovers’ tryst in a theatre.”

Eventually, as more flamencos toured to New York or, after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, settled here, Spanish dance began to take root and flourish. Each performer had her own style (and at first, they were mostly women) connected to her place of origin, training, and temperament. And yet, despite the differences, they began to form a kind of family; everyone in the show seems to be connected to everyone else in some way. An example is Santana herself, captured in a photo by Victor DeLiso wearing an extraordinary blood-red, orchid-like bata de cola, flounces billowing around her like sea foam, arms held proudly aloft. (A similar dress, belonging to another dancer, appears in a glass case in the show.) The American-born Santana was a student of María Alba, née Joan Fitzmaurice, a porcelain-skinned Irish American with Broadway aspirations. After seeing a performance by Carmen Amaya in the early fifties, Fitzmaurice was so impressed that she decided to remake herself as a flamenco dancer. She took a Spanish name (María Alba), studied with Mariquita Flores, and stopped speaking English. In the show, there is a film of Alba performing a seguiriya, with exquisitely precise foot- work and a serene, mask-like face.

Amaya, whose explosive, raw-edged dancing made her a pivotal figure in the New York flamenco scene, later starred in Los Tarantos, a 1963 film that introduced the young Antonio Gades, who would go on to make a series of important flamenco films with Carlos Saura, including Bodas de Sangre, Carmen, and El amor brujo. It is hard to pull oneself away from the clips of Gades’s hard-driving, sexy, almost anarchic dancing. In the nearby Bruno Walter Auditorium, as part of the ongoing flamenco programming, these three films were shown in full, along with several shorter pieces like Flamenco at 5:15, a documentary about teaching the flamenco style to dancers at the National Ballet School of Canada. The ancillary events also included conversations with the curators and a performance by the Flamenco Vivo Carlota Santana Ensemble.

An entire wall is dedicated to male flamenco dancers and their approaches to masculinity. One of them, Escudero— famous for his unaccompanied rhythmic improvisations—wrote a manifesto on the male esthetic in dance. José Greco, who danced with the Buenos Aires-born star Argentinita, was just as adamant: “The male must make no compromise with virility. He is unbending, dominating, and always the master.”

Despite his Spanish name and dark good looks, Greco was born in Italy and grew up in Brooklyn. Like many other dancers in the show, he often crossed over into the arena of less-than-authentic Spanish dance. The pursuit of “purity,” a slippery concept when discussing a dance form that is itself a hybrid of gypsy, Arab, and Spanish folk elements, did not become a burning issue until the irruption of Amaya’s fiery, “unschooled” style. The impresario Sol Hurok called her “the human Vesuvius.”

This taste for authenticity has returned in recent years as a counterweight to the wave of experimentation and fusion after the death of Francisco Franco. Dancers like the New York-based Soledad Barrio—depicted in her signature seguiriya—are attempting to bring the form back to a more spare, less theatrical mode, both in their own performances and through their teaching.

Some parts of the world depicted in the library’s exhibit are now, sadly, lost. The Beachcomber, a club with Polynesian décor located at Broadway and 50th Street, where many flamencos performed in the forties, is long gone. As is Fazil’s, a rehearsal studio on Eighth Avenue run by a former taxi driver, Fazil Cengiz. Cengiz rented space to everyone from Soledad Barrio and Mariano Parra to belly dancers and Japanese hip-hop dancers. In 2008, as the wall text explains, “Fazil’s was demolished to make way for condos.”