Over fifty-two years of quiltmaking, Ernest B. Haight created an extraordinary number of quilts, more than three hundred. At least twenty of them won ribbons at the Butler County Fair and the Nebraska State Fair. What was the secret to his success? An engineering background.

Haight invented a way to stitch several different fabrics side by side and cut across them to create large blocks of design, which he then assembled into a quilt. This streamlined technique allowed him to produce a quilt in a fraction of the time it took to traditionally hand-cut each piece and sew them together individually.

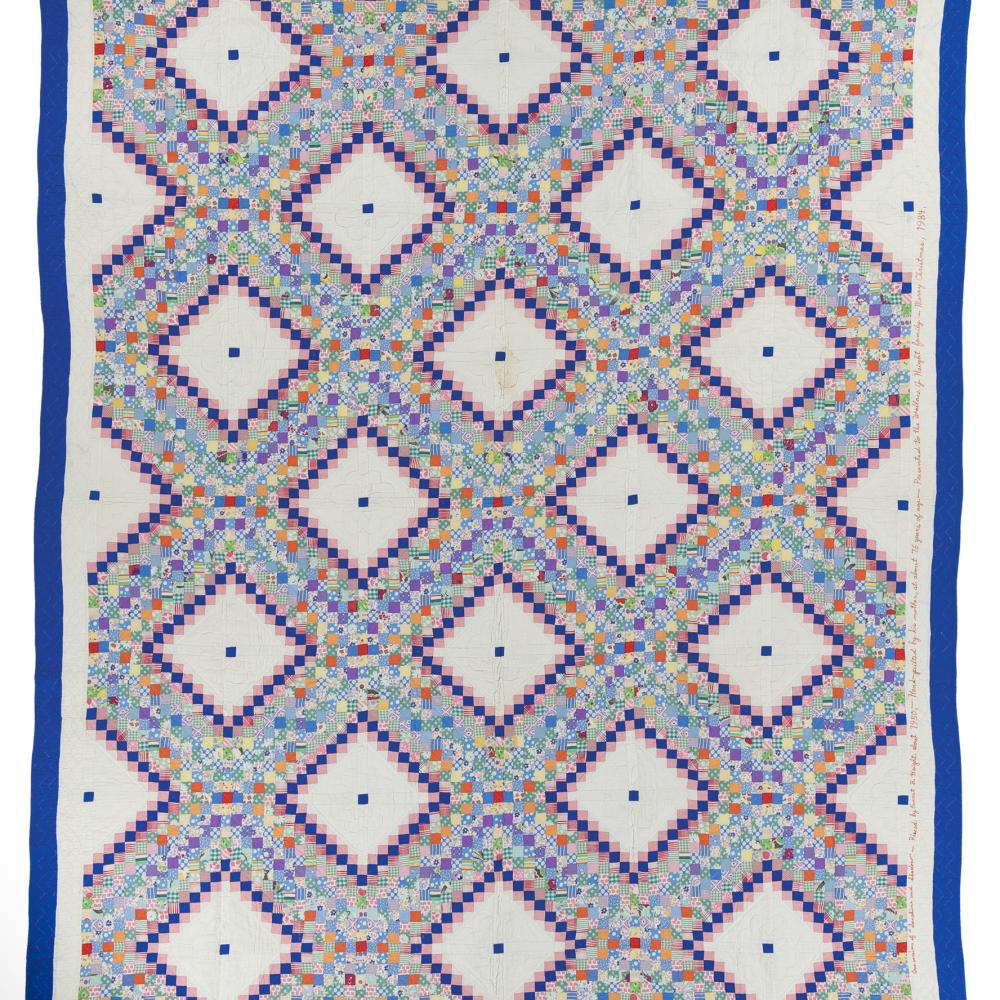

He liked to design quilts with hundreds of small pieces; his Quilt of a Thousand Prints, which he made in 1950, contains more than 4,500 squares of cotton fabric. Many of his quilts looked like stained-glass windows lit up with sunlight. Another design he favored resulted in quilts that looked like puzzles.

But he never would have achieved any of these accomplishments if not for that day in 1934 when he felt compelled to criticize his wife’s workmanship. Haight was irritated by the “lack of exactness” in the quilt she was making.

“If you can do any better, prove it,” Isabelle said. “Otherwise, keep still.”

A variety of Ernest Haight’s quilts are featured in the exhibit “The Engineer Who Could: Ernest Haight’s Half-Century of Quiltmaking,” which ran through March 2 at the International Quilt Study Center & Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska, with support from Humanities Nebraska.

Haight was born in 1899 on the Butler County farm his paternal grandparents had homesteaded in 1871. From his grandparents he had learned the importance of hard work and determination.

As a teen he loved to tinker in the machine shop on the farm. He built a two-cylinder steam engine and in another experiment caused a boiler explosion—ever the problem-solver, he modified the boiler to run on compressed air.

At the University of Nebraska he studied advanced geometry, math, design drawing, and physics. He graduated in 1923 with an arts and sciences degree and Phi Beta Kappa honors. The following year, he received his agricultural engineering degree and returned to the farm.

Haight enjoyed building intricately designed, three-dimensional wooden puzzles composed of interlocking pieces. One of his creations consisted of twenty-seven puzzles, 216 pieces, and measured only five inches in each direction. He used tweezers to assemble the harder-to-reach inner puzzles.

With such technical skills at his disposal, he turned to quiltmaking. Armed with the treadle sewing machine his mother’s parents had brought to Butler County by covered wagon around 1880, Haight went to work. He didn’t do any hand-sewing, which was labor intensive, but he could machine-sew a quilt top in eight to twelve hours.

Haight quilted mostly in the evenings and during the winter when his farm work was lighter. He pursued his new hobby secretly until the day when a neighbor walked in and caught him at his sewing machine. In 1951, he told an Omaha World-Herald reporter that quiltmaking “doesn’t necessarily make a fellow a sissy.”

In the late 1930s, Haight’s father, Elmer, who was seventy-eight at the time, learned of his son’s hobby and caught the quilting bug himself.

“If you can learn to piece a quilt,” he told his son, “I can learn to hand-quilt it.”

Elmer suggested that Haight piece a quilt for each of his children, who then ranged from one to eight years old, and the elder Haight would hand-quilt them. The quilts would be put away and given to each of the children on their wedding days.

After Elmer passed away in 1944, Haight’s mother Flora, and later Isabelle, took over the hand-quilting.

In 1960, Haight bought his first electric sewing machine, and in 1974 he self-published a twelve-page booklet, Machine-Quilting for the Homemaker. He retired from farming in 1972. With more time on his hands, the 1970s and 1980s were his most productive years. The renewed interest in quiltmaking that swept the country in the 1970s boosted Haight’s reputation.

Asked why he had taken up quiltmaking, Haight replied: “To relieve tension and to keep out of mischief.”

By the mid-1980s, Haight’s health was declining. He completed his last quilt in 1986, the same year that he was inducted into the Nebraska Quilters Hall of Fame. He passed away in 1992.