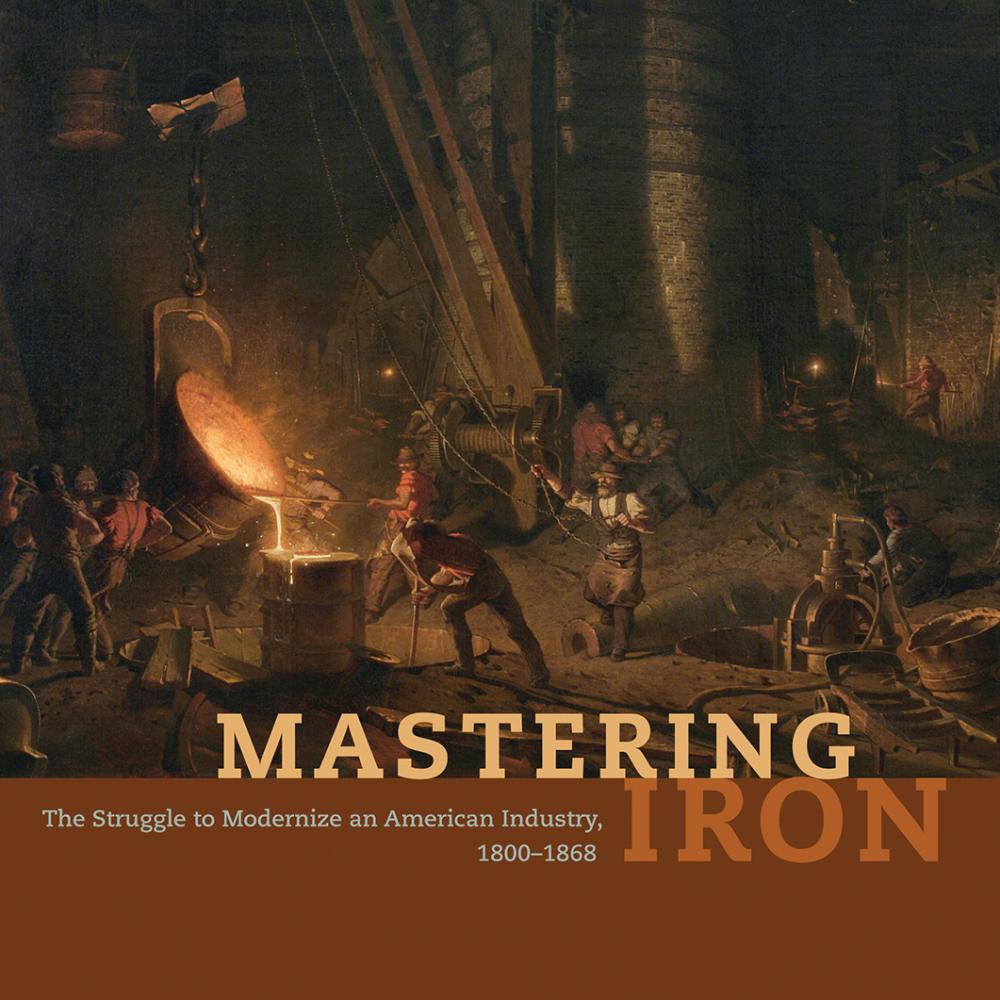

The “fiery industrial landscape” of ironworks attracted numerous poets and painters of the Romantic era. Robert Burns once sought access to Scotland’s huge foundry, Carron Company, but was turned away. Managers, fearing industrial spies, screened all visitors carefully.

“To outsiders like Burns,” writes Anne Kelly Knowles in the NEH-funded Mastering Iron: The Struggle to Modernize an American Industry, 1800–1868 (University Press of Chicago, 2013), “large iron works were fabulous, extreme places whose operations were difficult to comprehend.”

William Blake imagined the English industrial landscape beset with “dark satanic mills,” while much later a retired puddler from Shropshire echoed that appraisal: Working the iron in the furnace, he recalled, was “hotter than the bloomin’ hobs of hell.” American Walt Whitman took a much less Dantesque view in “A Song of Occupations,” cataloging “Iron-works, forge-fires in the mountains or by river-banks, men around feeling the melt with huge crowbars, lumps of ore, the due combining of ore, limestone, coal, / The blast-furnace and the puddling furnace, the loup-lump at the bottom of the melt at last, the rolling-mill, the stumpy bars of pig-iron, the strong, clean-shaped T-rail for the railroads.” Moreover, painters commonly portrayed British iron towns as “smoking ruins . . . prey to the devouring element” of fire, while “depictions of American iron landscapes are more varied, . . . nestled comfortably in the countryside, the ironworks a quiet pocket of productivity.”

In Mastering Iron, Knowles notes in her opening chapter how little attention U.S. ironworks have gotten from historians, compared with that given the steel industry. She devotes the following chapter to the diverse social aspects of the iron industry across a wide swath of geography. “Company owners, managers, and skilled workers struggled to various extents to implement technologies that had been developed in very different geographical contexts in Britain.” The concentration of resources, transportation, and population centers in Britain didn’t have a close parallel in the United States. Despite the impressions that nearly all ironworks were located in Pennsylvania, in fact, they were spread out from the New England states to Alabama, with many important points of production in Maryland, Virginia, and Tennessee. Knowles couldn’t have determined the “regional patterns of technology and production, or the temporal dynamics of the iron industry, without the exploratory mapping that geographic information systems made possible.”

The extreme places that fired the imaginations of so many painters were generally found in Britain, while ironworks in the United States—aside from those in Pittsburgh, Wheeling, and Philadelphia—were often rural. There were iron plantations, hamlets, villages, and company towns. One period painting of the West Point foundry, for example, shows that it was “nearly invisible in the embrace of woodland.”

While the drama of the inferno that often enlivens paintings of British ironworks is not center stage in American depictions of the industry, Rebecca Blaine Harding, in Life in the Iron Mills, described the environment stateside as remarkable nonetheless: “The idiosyncrasy of this town is smoke. It rolls sullenly in slow folds from the great chimneys of the iron-foundries, and settles down in black, slimy pools on the muddy streets. Smoke on the wharves, smoke on the dingy boats, on the yellow river,—clinging in a coating of greasy soot to the house-front, the two faded poplars, the faces of the passers-by. The long train of mules, dragging masses of pig-iron through the narrow street, have a foul vapor hanging to their reeking sides.”

Knowles reminds that the industry played a considerable role in easing domestic life through the production of many consumer products, including cast-iron pots, pans, and cookstoves. In 1825, a piano maker even patented a cast-iron frame that assured the safe transport of the delicate instrument to parlors across the country.