When Ferdinand A. Brader (1833–1901) left Switzerland for America in the early 1870s, he carried with him the skills of a mold-maker and a baker.

Born and raised in the Swiss town of Kaltbrunn, Canton of St. Gallen, he worked in a textile mill and in a bakery owned by his mother. He probably also had knowledge of the neighboring folk art tradition known as Bauernmalerei, or “farmer art,” prevalent from 1600 to 1900 in the adjacent Swiss regions of Appenzell and Toggenburg.

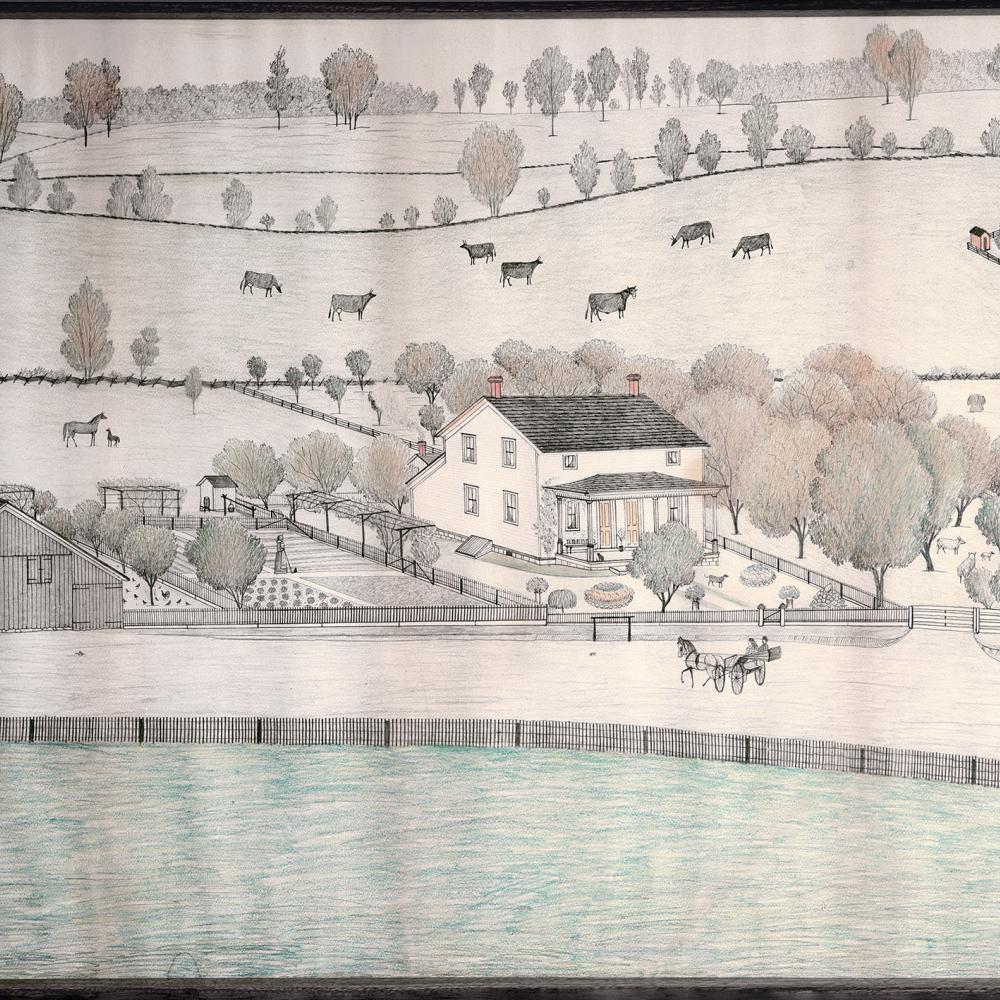

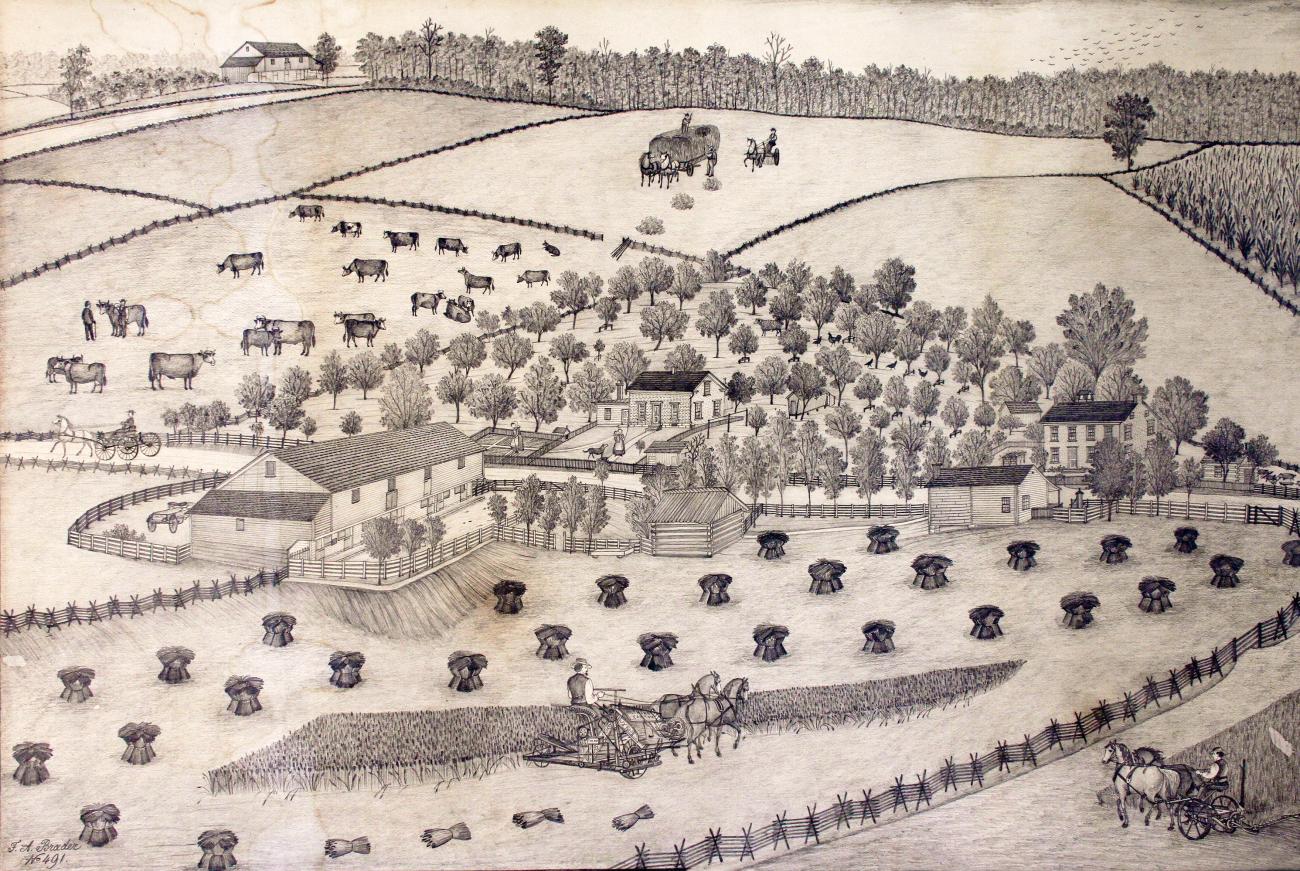

As far as we know, this was his only exposure to drawing similar to what would become his trade: Creating large-scale (usually about fifty by thirty inches), bird’s-eye perspectives of farms in Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. Hundreds of his works offer an extraordinary and intimate view of what rural life was like at the end of the nineteenth century.

Early beer-brewing operations, cheese production, everyday farming life—these are all topics found in Brader drawings that he brought to life in minute detail. His drawings illuminate not only the late 1800s in Ohio and Pennsylvania, but Brader’s importance as an artist-chronicler of the time and place.

Art historian and fine-art appraiser Kathleen Wieschaus-Voss first saw these extraordinary drawings in private homes in Stark County, in Ohio’s Amish country. She fell in love with them for their straightforward, factual approach to late nineteenth-century farm life, just at the moment before the incursion of widespread mechanized production.

“I was enchanted by the detail and charm of the drawings and recognized their historical significance,” recalls Wieschaus-Voss. She soon developed a database to keep records of the numerous drawings.

Subsequently, Wieschaus-Voss became the guest curator for the Canton Museum of Art’s exhibition "The Legacy of Ferdinand A. Brader: 19th Century Drawings of the Ohio and Pennsylvania Landscape." The retrospective exhibit mounted more than forty of the graphite pencil drawings by the itinerant folk artist who captured views of daily life on family homesteads and businesses during his travels through rural counties of Pennsylvania and Ohio. The exhibit, which was made possible in part by support from Ohio Humanities, brought Brader to the public’s attention for four months during the past winter.

The exhibition and Weischaus-Voss’s passion have stirred more and more of Brader’s drawings to the surface. “By autumn of 2011,” Wieschaus-Voss notes, “my database comprised records for 108 drawings. Since then, with the help of hundreds of volunteers in Ohio, in Pennsylvania, and across the country, the list of known landscape drawings has more than doubled.”

Those efforts led to the identification of well over two hundred Brader drawings from what is believed to be a lifetime total of at least 980, a sum derived from Brader’s practice of identifying the owners and township of each property he drew and using a sequential numbering system for the drawings. Many of these drawings have been cherished, handed down through generations, and, still proudly displayed in family homes.

Although married and a father, Brader made his way alone from Switzerland to Berks County, Pennsylvania, then a well-known German-speaking region, where a May 22, 1880, newspaper article in the Reading Times declared that the “tramp” artist (a term that he strongly protested and had retracted) had completed ninety drawings of local farms and homesteads since July10, 1879, the earliest known citing of his work.

Brader had come to the United States following his brother, Josef Sebastian, and traveled extensively in Pennsylvania and Ohio. As payment for room and board, often in a barn, he created large pencil drawings of the farms and properties where he was given temporary residence. Why he came here remains a mystery. Although researchers have uncovered family stories that brother Sebastian “found the gold” in America, it’s now known he died in 1879 in a military hospital from wounds suffered as a Northern conscript in the Civil War.

Historian Andrew Richmond created and curated a companion exhibit, "The Views of Ferdinand A. Brader: An Historical Perspective," which provided an art historical context for Brader’s work, indicating that Brader was by no means the only traveling artist to target prosperous American farmers at this time.

While he focused on counties in Pennsylvania and Ohio, other artists like Fritz Vogt drew homesteads and farms in New York, and Herman Markert worked in central Pennsylvania doing similar work at similar prices, according to “The Life of a Traveling Swiss Artist: Known Facts and Times of Ferdinand A. Brader” by Bristol Lane Voss in the exhibition catalog.

Bringing Brader and his customers together was a popular post-Civil War tome, the county atlas, based on government surveys and maps, which cost the handsome sum of $10, prepaid. For an extra fee it could also include a lithograph of the family farm or house. Voss cites the February 16, 1880, edition of the Reading Times reporting Brader sold his Pennsylvania drawings for up to $4.25 each, far less than the atlas. Sometimes he didn’t even get that. A newspaper reported that Brader was threatened with a handgun when he tried to collect the balance of $3 from one of his customers.

By comparison, the New York Times reports that Sotheby’s sold a Brader drawing last January for $37,500 and that Hirschl & Adler Galleries, who loaned works to the Canton exhibit, “has Brader scenes in stock for up to $125,000 each.”

While best known for his farmstead pictures, Brader also recorded scenes of both the Portage and Stark County Infirmaries; railroad stations; and rural industries, such as grist mills, potteries, mines and quarries, a vineyard, cheese making, a fertilizer plant, carriage shop, and undertaking business. His last known drawing was done in Stark County in 1895.

“Although the Swiss artist spent only a dozen years of his life here, our county was his home base during the years in which he produced well over 600 of his 980 drawings, before returning home to Switzerland in 1896,” says Wieschaus-Voss.

In early 1896, several Ohio newspapers, including The Repository, reported Brader’s disappearance from Ohio, and later confirmed that he had returned to his home in Switzerland to collect an inheritance. However, five years later in 1901, Swiss officials declared Brader “lost and missing, without a trace.”