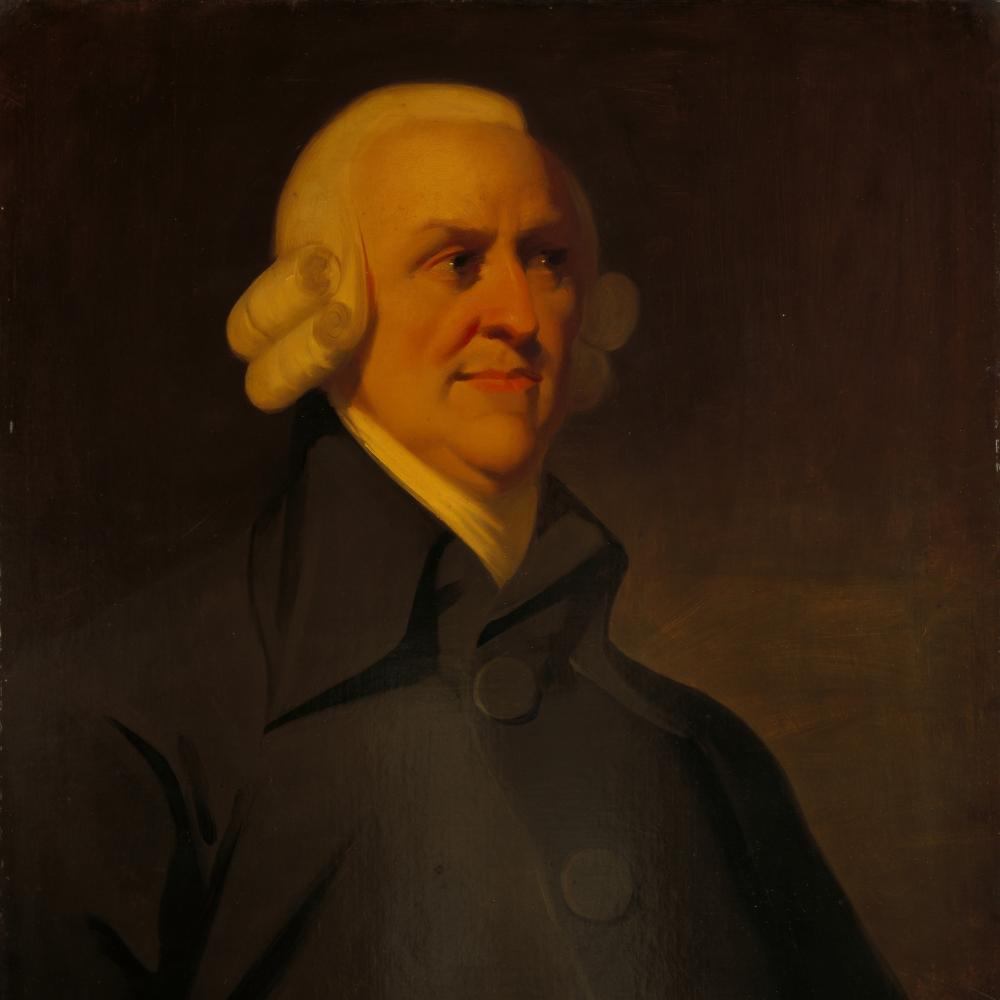

For this edition of IQ, we are rummaging around in Adam Smith’s brain with Jack Russell Weinstein, professor of philosophy at the University of North Dakota. Weinstein also moonlights as the host of “Why? Philosophical Discussions about Everyday Life,” a show on Prairie Public Radio supported by the North Dakota Humanities Council. His most recent book, Adam Smith’s Pluralism: Rationality, Education, and the Moral Sentiments, was written with the help an NEH fellowship.

How did you get hooked on Adam Smith?

It was an accident, really. The only political philosophy course offered during my first semester of graduate school was on Adam Smith. I read The Theory of Moral Sentimentsand wrote a midterm paper called “Can men teach women’s studies?” That was in 1991; I have been rewriting it ever since.

This is the first of three planned books about Smith. What makes him good company?

Getting to step out of the prescribed liberal/conservative dichotomy is wonderful. It’s really nice to discuss justice with someone who isn’t a partisan. But also, Smith is a wonderful writer and a generous scholar. The Wealth of Nations paints with such broad brushstrokes; it’s awe-inspiring.

Let’s help our readers who might be rusty on Smith’s philosophy. The Theory of Moral Sentiments is important because?

It is a work of moral psychology, which means it tries to describe how people actually make moral decisions and how they develop a conscience. It also describes how to be virtuous, happy, just, and prosperous. It ends up being one of the founding texts in sociology and had an influence on nineteenth-century literature. Smith argues that we have to cultivate our imagination to genuinely enter into the lives of other people.

And An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations?

It’s one of the most influential books in history and the blueprint for what would one day be called capitalism. Smith argues that you don’t measure the wealth of a nation by counting all the money within its borders at one time. Instead, you measure the labor and production. So ask yourself, who is wealthier, an unemployed person with $50,000 in the bank, or a person with a secure job who has $30,000? Clearly, it’s the second. This was a major challenge to mercantilism, which would later be called protectionism. Smith is pro-free trade and globalization, and in favor of increased individual religious and social freedoms. He believes in the idea of progress. But he’s also in favor of universal education and doesn’t believe that everything is subject to the market. Regulation is important, as are the public humanities.

Who are Smith’s acolytes?

We all are, of course. We live in a Smithian world, even his critics.

Who are his naysayers?

Karl Marx, of course. But the thing about Marx is that while he is capitalism’s most fervent critic, he was also history’s best Smithian. His philosophy of history is largely Smith’s, with communism tacked on to the end.

Common misconception about Smith that you’d like to correct?

He’s not a libertarian and he doesn’t think that everything should be subject to a market. He also doesn’t belong to either Republicans or Democrats; he shares ideas with both. But I guess the biggest misconception is that he’s an economist; he’s not. He’s a philosopher who wrote on morality, aesthetics, logic, rhetoric, sociology, psychology, anthropology, and so much more.

You’re interested in Smith’s views on pluralism. Did the concept exist in his era?

The word pluralism as we understand it doesn’t appear until 1924 and variations on it show up just a bit earlier. But the idea has a long history. Augustine’s City of God is a book on pluralism, albeit an all-Christian version, and there is a thin thread of discussion that runs through Spinoza and John Locke and others. But what we mean by pluralism—coexistence and mutual governance by diverse cultural groups—only starts to appear around Smith’s time. Before then, the discussion is largely about the rulers being kind to people under their power.

Would Smith have been friendly to the idea?

I think so. Smith is vociferously antislavery. He is pro-worker and pro-women. He believes in global relationships, forcing us to ask why we care more about our neighbors than those half a world away. He argues for religious openness and toleration, and upward mobility. He is sensitive to issues of colonialism and complains in his letters about English attitudes toward the Scots. He also endorsed American independence. But, of course, we don’t really know.

Who has been your favorite guest on your radio show?

Hal Herzog made me laugh uproariously and Mary Jo Bang made me cry (really). Tony Kushner made me feel like the coolest kid in class and Carol Gilligan felt like a dear old friend. Talking to Amartya Sen was a dream come true.

Dream guest?

Adam Smith, of course, but he’s not returning my emails. I would really love to interview Steve Martin about the philosophy of humor and Ariel Levy who, I think, is the best journalist writing on gender today. George Lucas, Simon Pegg, B. B. King, Elie Wiesel, and Oprah Winfrey are all on the list, as is my wife, Kim Donehower, who would be brilliant. Talking philosophy with people who don’t do philosophy, while really difficult, is revealing and interesting. I wonder what it would be like to talk to Miley Cyrus as a philosopher, as a thinking person and not just as a semi-clad body in the crosshairs of the Internet. It could be a disaster. It could also be a breakthrough for public philosophy.