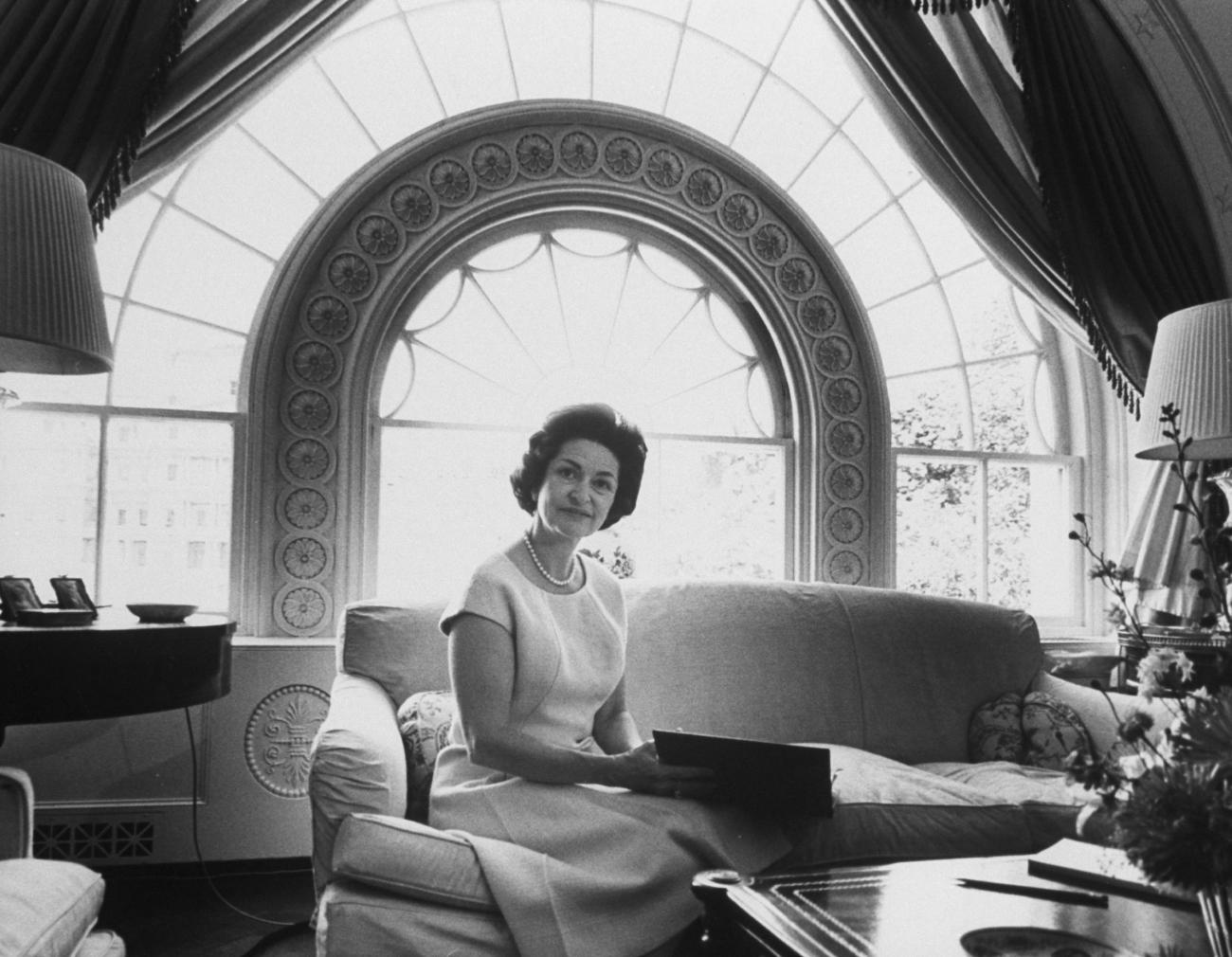

Just before dawn on Tuesday, October 6, 1964, the Lady Bird Special pulled away from Track 12 at Union Station. Over the next four days, the nineteen-car train carried First Lady Claudia “Lady Bird” Johnson on a whistle-stop tour of the South, covering 1,682 miles from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans. Johnson wasn’t going to be sitting quietly and smiling pleasantly while her husband did all of the talking. Instead, she was going to make speech after speech from the back of the train, telling folks in towns big and small why they should vote the Democratic ticket. Before it was over, she would make forty-seven speeches, shake hands with more than one thousand Democratic leaders, and speak before more than two hundred thousand people. It was the first time that a first lady had campaigned alone, without her spouse. Not even Eleanor Roosevelt had done it.

Laura Bush, Michelle Obama, and other first ladies have stumped for their husbands. But, in 1964, it was a decidedly uncommon event, made more so by Johnson’s choice of where to go. The South had become hostile territory for Democrats because of the party ’s role in championing civil rights. And no candidate was more identified with civil rights than Lyndon Baines Johnson.

Several factors made the 1964 election especially contentious. President Kennedy had been assassinated, Cold War hostilities with the Soviet Union were a grave concern after the Cuban Missile Crisis, and Americans had good reason to feel they were living through a moment of great social change. President Johnson had become the major advocate of civil rights legislation among officeholders, while the Republican candidate, Senator Barry Goldwater, tapped into a significant stream of negative feeling against an activist federal government.

The campaign was extraordinarily negative: Democrats showed, though only once, the famous “Daisy” ad, equating a Goldwater presidency with nuclear destruction. Critics of the civil rights movement used blatantly racist language and the threat of violence to make their case.

Goldwater had voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which LBJ had maneuvered through Congress with skills he had learned over three decades on the Hill and by invoking the fallen president’s memory. Goldwater, an early favorite, had stumbled badly, and, with two months to go before Election Day, the momentum clearly favored Johnson, who, craving validation, wanted a margin of victory large enough to smash any doubts that he had gotten to the White House on his own steam.

In September, a Gallup poll gave Johnson a 69 percent to 31 percent lead. So far ahead, the Johnson campaign could have ceded the South to the Republicans. Even if every state in the region went for Goldwater, Johnson could still garner almost 400 electoral votes, far surpassing the 270 needed to win. But Johnson wasn’t a man to shrink from a fight, and Lady Bird believed an effort needed to be made to court Southern voters. As a native of Texas with relatives in Alabama and Louisiana, the first lady knew there was more to the South than angry white men who opposed civil rights.

“I have a strong sentimental, family, deep tie to the South, and I thought the South was getting a bad rap from the nation and indeed the world,” she recalled years later in her oral history. “It was painted as a bastion of ignorance and prejudice and all sorts of ugly things. It was my country, and although I knew I couldn’t be all that persuasive to them, at least I could talk to them in language they would understand. Maybe together we could do something to help Lyndon and then perhaps to change the viewpoint of some of those newspaper people who were traveling with me.”

The extensive oral history that Lady Bird did in conjunction with the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library reveals a gracious woman who continued to grow with each new challenge thrust upon her. Michael Gillette, director of Humanities Texas, conducted the majority of the interviews and has edited the newly declassified transcripts into the highly readable Lady Bird Johnson: An Oral History, from which some of the material for this article was drawn.

The whistle-stop tour was in many ways a culmination of Lady Bird’s political education. At loose ends after finishing a journalism degree at the University of Texas, she fell hard for Lyndon, a strapping, dark-haired law student with a boisterous personality and ambition enough for both of them. After an intense ten-week courtship by letter, she agreed to marry him. When Lyndon ran for Congress in 1937, she used her inheritance to stake his campaign. When he went off to fight in World War II, she ran his congressional office. Even after the birth of their two daughters, Lynda (1944) and Luci (1947), her involvement continued to grow. “She was faced with a dilemma in her life as to whether she would make her husband’s career her top priority or whether she would stay home with her daughters. She chose the former,” says Gillette.

Johnson also became more confident in her abilities. “Nineteen forty-eight was really her debut,” says Gillette of LBJ’s successful campaign for the Senate. “She did more than say thank you for the barbecue and sit down. She gave a full-blown speech and went around the state campaigning for LBJ.” As her public role expanded, Johnson enlisted a speech coach to help fine-tune her delivery. During the 1960 presidential election, Kennedy asked Johnson if she would court the women’s vote in place of his wife, Jackie, who was pregnant and worried about a miscarriage. She logged thirty-five thousand miles, eleven states, and one hundred fifty events with her husband.

Before embarking on the whistle-stop tour, she told the Christian Science Monitor, “For me, and probably for most women, the attempt to become an involved, practicing citizen has become a matter of evolution rather than choice. Actually, if given a choice between lying in a hammock under an apple tree with a book of poetry and watching the blossoms float down, or standing on a platform before thousands of people, I don’t have to tell you what I would have chosen twenty-five years ago.”

All Aboard!

The original idea for a whistle-stop tour came from Harry Truman, who had suggested that LBJ undertake one for the 1960 election. “You may not believe this, Lyndon,” said Truman, “but there are still a hell of a lot of people in this country who don’t know where the airport is. But they damn sure know where the depot is. And if you let ‘em know you’re coming, they’ll be down and listen to you.” Over the course of five days in October 1960, LBJ covered eight southern states and thirty-five hundred miles. Now it was Lady Bird’s turn. Whereas the president had been waging a bare-knuckle brawl, the first lady would wage a charm offensive. She would talk about her husband’s accomplishments, the goals for his administration, and how the federal government had helped each community. She would praise local heroes. What she wouldn’t do was scold southerners about civil rights.

The tour, organized out of the East Wing, was primarily a woman-planned, woman-run operation. Johnson had the capable and charming Bess Abell as her social secretary and Liz Carpenter as her press secretary and staff director. A former reporter, Carpenter had cut her teeth on the Kennedy-Johnson campaign and went on to serve as the vice president’s executive assistant, the first woman to hold the position. Kenny O’Donnell, LBJ’s principal campaign adviser, wasn’t sure Lady Bird’s plan would work. “He sat sphinx-like in meetings with me—half laughing at the whole idea and obviously feeling that neither the South nor women were important in the campaign,” wrote Carpenter in her memoir, Ruffles and Flourishes. The president, however, loved the idea and pored over maps with the first lady, tracing railroad lines and making suggestions for where to stop.

The trip also received a helping hand from congressional wives—Lindy Boggs of Louisiana, Betty Talmadge of Georgia, and Carrie Davis of Tennessee. Virginia Russell, wife of Donald Russell, the outgoing governor of South Carolina, stayed for three weeks in a guest room at the White House to assist with the planning. “The South may have its shortages—in nutrition and education—but I will match the political talents of Southern women against any others, anytime and anyplace,” wrote Carpenter. “They have the uncanny ability to look fragile and lovely as a magnolia blossom, and still possess the managerial ability of an AFL-CIO organizer.”

The first lady spent Friday, September 11, personally calling governors and congressmen in the eight states that she would pass through to invite them to board the train. North Carolina senators Sam Ervin and Everett Jordan said yes, but Senator A. Willis Robertson of Virginia would be away hunting antelope. Harry Byrd of Virginia also declined, citing the recent death of his wife. Byrd may have been in mourning, but the pro-segregation senator was also quietly organizing “Democrats for Goldwater.” As an antidote to the Lady Bird Special, he arranged for Strom Thurmond, South Carolina senator and die-hard Dixiecrat, to campaign for Goldwater on the day the first lady passed through Virginia. Thurmond, of course, politely declined Johnson’s request, but South Carolina’s senior senator, Olin Johnston, accepted. Lady Bird knew better than to ask Alabama governor George Wallace, a virulent segregationist. “I doubt it would even be courteous to do so,” she recorded in her diary.

Tuesday, October 6

The Lady Bird Special departed Washington just before dawn. The jewel of the train was the “Queen Mary,” a special observation car built thirty-four years earlier by the Wabash Railroad and rescued from a Pennsylvania junkyard. The car had received a hasty makeover, starting with a shiny new red, white, and blue paint job on the exterior. A brass platform for speechmaking was fitted on to the back. The inside of the car, which served as a rolling reception room, was painted light blue and decorated with family photos and campaign posters. For all of its old-school charm, the “Queen Mary” lacked modern air-conditioning, requiring a constant supply of ice to keep the car cool. At each stop, an advance man from the campaign arranged for blocks of ice to be loaded onto the base of the train. The next to last car consisted of living and sleeping quarters for Johnson and her daughters. Painted a deep green, it was quickly dubbed “the green room of the White House.”

The remaining cars were stuffed to capacity with campaign staff and more than two hundred reporters, who ranged from old political hands to foreign correspondents, eager to see the traveling spectacle. To help “Nawthern” reporters understand the South, Carpenter prepared a tongue-in-cheek “Dixie Dictionary.” “Tall cotton” was what southerners walk through due to Johnson prosperity. “Kissin’ Kin” was anyone who would come down to the depot. A “Fat Back” was a rich Democrat who had turned Republican, but now had the good sense to return to the Democratic fold. Frances Lewine, a reporter for the Associated Press, filed a story about the dictionary, only to have it yanked from the wires for containing “objectionable material.”

A dining car kept reporters nourished with Southern-inspired snacks and Johnson family favorites—everything from pickled okra to crab dip to guacamole and chili con queso. The recipes were printed up in newspapers, so others could have a taste of Johnson’s hospitality.

As the Lady Bird Special made its first stop in Alexandria, Virginia, the sun was barely poking above the Potomac River. Five thousand people turned out to see the first lady, who wore an “American beauty red wool dress and jacket,” and her daughter Lynda, who sported a “black and white checkered jacket and elbow length blue gloves.” Three high school bands played “Yellow Rose of Texas.”

“I wanted to make this trip because I am proud of the South and I am proud that I am part of the South,” Johnson told the crowd. The country needed to look for the ties that “bind us together, not settle for the tensions that tend to divide us.” She praised the response of local government across the South to the civil rights law. The crowd didn’t cheer that line, nor did they roar when the president, who had come to see his wife off, mentioned his running mate, Hubert Humphrey, a senator from Minnesota with a strong record on civil rights.

After kissing his wife on the cheek, LBJ boarded a helicopter for the short trip back to the White House. But Lady Bird wasn’t alone. Louisiana congressman and majority whip Hale Boggs signed up as her escort for the entire trip. She also had her staff, congressional wives, and a phalanx of Secret Service agents. A steady stream of guests boarded at each stop, with the travel time between stations used for photographs and chitchat. To keep from being over-whelmed with flowers, which appeared by the bushel, arrangements were made for bouquets to be given to hospitals and retirement homes farther up the line.

The train stopped next in Fredericksburg, Ashland, Richmond, and Petersburg. Five miles out from the depot, the speakers on the train started blaring, “Hello Lyndon!” Composer Jerry Herman, a Johnson supporter, had rewritten the words to the title song from his smash Broadway hit, Hello Dolly! “Hello, Lyndon! Hello, Lyndon! It’s so nice to have you there where you belong!” To ensure that crowds turned out to greet the train, more than sixty “advance women” had descended on towns along the route three or four days before the whistle-stop tour ’s arrival. They met with local officials, courted garden and community clubs, and put out press releases. “One of them was named Mrs. Robert E. Lee, and I wish to gosh every one of their names had been Mrs. Robert E. Lee,” said Carpenter in her oral history.

For the brief stops, which lasted between five to twenty minutes, Johnson and the politicians who had joined her would speak from the back of the train. As they talked, fifteen hostesses with Southern drawls, outfitted in Breton straw sailor hats, royal blue dresses, and white gloves, floated through the crowd, handing out peppermint taffy, balloons, buttons, pennants, and campaign memorabilia.

After stopping in Suffolk on the way to the Atlantic coast, the train rolled into Norfolk at midday for a rally and flag-raising ceremony at Norfolk Civic Center. More than fifteen hundred people lined the five-block route, while another five thousand gathered on the center ’s plaza, along with high school bands and rifle squad.

From Norfolk, it was on to North Carolina, where the first stop was Ahoskie, a town of forty-five hundred. The sheriff estimated, however, that ten thousand people turned out to see the first lady. “This is the second biggest crowd we’ve had since Buffalo Bill brought his Wild West show here in 1916,” a resident told the Chicago Tribune. In A White House Diary, Johnson recalled a woman in Ahoskie who pushed her way through the crowd to shake her hand. The woman said, “I got up at 3 o’clock this morning and milked twenty cows so I could get here by train time!”

Large crowds and a growing number of protestors turned out to see her in Tarboro, Rocky Mount, and Wilson. During the planning for the trip, Carpenter, worried about the vagaries of press interest, had told the president that she thought they would “need beefing up by the time we get to Raleigh.” LBJ responded, “I’ll be there.”

After a stop in the little town of Selma, the train rolled into Raleigh, and LBJ joined Lady Bird for a rally at North Carolina State College. Fourteen thousand people jammed Reynolds Coliseum. Carpenter ’s plan worked. Reporters who might have passed on covering the first lady could not ignore a campaign stop by the president, and Lady Bird’s spirits were lifted. “He knew we needed a stimulant then to keep the train going,” she said in her oral history. “I always felt that he was sorry he wasn’t along every bit of the way.”

Wednesday, October 7

Before noon, the Lady Bird Special stopped in Durham, Greensboro, and Thomasville. Twenty-five thousand people gathered for a lunchtime rally at Charlotte’s Independence Square. In early afternoon, the train crossed into South Carolina, stopping first in Rock Hill, a town that made headlines in February 1961 when nine African-American men were arrested for attempting to desegregate a lunch counter. Then, in May of that year, a bus carrying the original thirteen Freedom Riders, a group dedicated to desegregating interstate travel, arrived in Rock Hill. Three of the riders, one of whom was John Lewis, attempting to enter the whites-only waiting room in the Greyhound bus terminal, were beaten by a group of white men.

Three years later, Johnson was received as a friendly visitor. “The sign on the dusty railway station said ‘Rock Hill,’” reported the Charlotte Observer. “But for 10 thrilling minutes Wednesday it was Petticoat Junction—and the men in the First Lady ’s party took a back seat. Eight thousand yelling, cheering people looked right past a governor, a senator, and dozens of other high-ranking Democrats. They fastened their eyes on a dark-haired woman in a red dress and on her pretty daughter, dressed in green. . . . The roar of approval left no doubt that the thousands gathered here were glad to claim the First Lady as a kissin’ cousin.”

At every train stop, reporters mingled with the crowd in search of local color, which is how Gloria Negri, reporter for the Boston Globe, found herself stranded in Chester. Before the train departed, a bell sounded to let the reporters know that they had two minutes to get back on the train. Unable to make the step up, Negri watched as the Lady Bird Special pulled away, the sound of “Happy Days Are Here Again” trailing in its wake. Carpenter had told reporters that if they were left behind, they should find the campaign’s advance man for a lift to the next stop—or better yet, stay in town, become a resident, and vote for Johnson.

When she couldn’t find the advance man, Negri appealed to Chester ’s deputy sheriff, William L. Nunnery, for help. At first the deputy didn’t believe her story, suggesting that she might be a Republican spy. “But chivalry is not dead in the South,” declared Negri. With the siren screaming and the speedometer reaching eighty on the twisting back roads, Nunnery gave Negri a ride to the next stop, arriving in Winnsboro as the Lady Bird Special pulled in.

After Chester and Winnsboro, the train stopped in Columbia, where Johnson encountered her first serious group of protestors. Goldwater supporters chanted “We want Barry!” upon her arrival. By the time the first lady and her contingent stepped onto the speaking platform in front of the station, a vocal war of “We want Barry!” versus “We want Lyndon!” had erupted. The hecklers quieted down for the prayer, but fired up again as Johnson was about to begin her speech. The first lady, sun glaring in her eyes, faced the crowd without her usual smile.

She spoke of LBJ’s role in negotiating the Test Ban Treaty. “That treaty came at the end of a long, hard path of negotiations, and my husband is proud to have played a part in gaining this measure of safety for the people of the world.” The heckling started again, but she’d had enough. Lifting her white gloved hand, she silenced the Goldwater supporters: “This is a country of many viewpoints. I respect your opportunity to express your viewpoint. Now it’s my opportunity to present mine.”

More hecklers awaited Johnson in Orangeburg, a John Birch stronghold. Her reception grew less gracious with each stop, which she knew would happen. “In 1964, anybody could go to Atlanta and speak out for civil rights and still get out with their hides on,” observed Carpenter. “She told us to give her the tough towns. And so we took Charleston.” There, she again appealed for civility, but failed to sway the Goldwater supporters, who drowned out her speech with their chants and boos. One heckler told the New York Times that the president was communist because “he supports niggers.”

Thursday, October 8

Before leaving Charleston, Johnson toured The Battery by carriage, forcing more than a hundred reporters on foot to try and keep pace with a bay mare named Jimmy and a palomino named Sport. Touring the antebellum homes with their pastel facades and sprawling white verandas would have offered a pleasant break, if not for the signs on one door after another saying, “This House is Sold on Goldwater.”

Next, the train headed for Georgia and the Deep South, beginning the two most challenging days of the trip. In Savannah, a crowd of 15,000 turned out for a lunchtime rally. The Goldwater supporters were also back, carrying signs that read, “This is Goldwater Country ” and “Down the Drain With Lyndon Baines.” When a pastor tried to deliver the invocation, he was drowned out with shouts of “We Want Barry!” Georgia governor Carl Sanders, a Democrat who supported desegregation, received similar treatment. The first lady talked right through the taunts, and even shook the hand of one of the protestors. When the Chicago Tribune asked the hecklers why they had come, one replied: “If we hadn’t come, the newspapers might have said ‘Savannah is solidly behind Johnson.’ It’s not.”

As the train made its way from Georgia into Florida, the Secret Service received an anonymous tip about a bomb threat. Before the train made its way across a seven-mile bridge, the FBI and local law enforcement officials surveyed it for explosives. Despite the “all clear,” the train received an escort by boat, while a helicopter kept watch overhead.

Friday, October 9

The final day of the whistle-stop tour was a whirlwind ride through Florida’s panhandle, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. With each stop, Johnson’s accent grew a little thicker, a little more Southern. After stops in DeFuniak Springs, Crestview, Milton, and Pensacola, the Lady Bird Special rolled into Alabama. In Flomaton, population twenty-five hundred, Johnson told the crowd how her summer vacations consisted of “swimming in the creek, watermelon cuttings, hayrides and visiting aunts and cousins in Selma and Montgomery and Billingsley and Prattville.” Also waiting for her at Flomaton was a grand bouquet of red roses sent by Governor George Wallace, a very unexpected gesture.

In Mobile, the Goldwater supporters were back, but so was Johnson’s inherent graciousness. “Mrs. Johnson was the most relaxed, the most fiery and the most appealing of all the days of her history-making whistlestopping tour of the South,” declared the Chicago Tribune. “Ah’m home,” Johnson told the enthusiastic crowd who had gathered in front of Phoenix No. 6, a restored firehouse, in downtown Mobile. After dedicating the firehouse, Johnson received the key to the city and was made an honorary chief of the fire department.

“I am proud to be in a state where my mother and father were born and raised and being in Mobile is in part a sentimental journey for me. I’m mighty glad to be in that part of the country where, although you might not like all I say, at least you understand the way I say it,” she told the crowd. “Standing here today, I feel that having spent so many summers of my past here and having traveled quite some since, I can speak of what the new South means to the nation. I can talk about the warmth and courtesy of the South of my youth, which will never change, and about the new South that I saw at Huntsville where man turns his face to the moon, and the new South I see here in Mobile.”

In Mississippi, the train made one stop, in Biloxi, where Johnson emphasized how Keesler Air Force base, home to 17,000, pumped federal dollars into the local economy. It was a tactic she’d used repeatedly over the previous three days: keep mum on civil rights while reminding the local residents of how the federal government helped their community.

Johnson passed through Mississippi without incident, but not for a lack of trying on the part of the Ku Klux Klan. During a hearing before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in January 1966, testimony revealed that Louis Di Salvo, a barber and gunrunner for the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi, had attempted to recruit the KKK chapter in Poplarville to bomb the Lady Bird Special as it passed through the state.

After Biloxi, there was only one more stop, New Orleans, the culmination of the four-day trip. When the Lady Bird Special pulled into Union Station, the president was waiting with open arms for his wife. “Mrs. Johnson embraced her husband as if they had been separated for three years instead of three days, and prolonged the clasp for the benefit of television cameras,” wrote the Chicago Tribune. Forty thousand supporters, mostly African American, had also been bused in for the rally.

“This was not only a sentimental journey, but a political one,” she told the crowd. “I came because I want to say that for this president and his wife, we appreciate you and care about you, and we have faith in you.” She and the president had “too much respect for the South to take it for granted and too much closeness to it to ignore it.” Johnson also made her first reference to civil rights since the send-off in Alexandria, Virginia. “I do not believe that the majority of the South wants any part of the old bitterness, and the more I have seen these last few days, the more I know that is true.”

The first lady’s work, however, wasn’t done. She and the president made their way down Canal Street, riding in an open car, to attend a campaign fund-raising dinner at the Jung Hotel. At the dinner, LBJ delivered a speech that would further help to galvanize his campaign, presenting himself as a statesman who would not shrink from taking a stand. “If we are to heal our history and make this nation whole, prosperity must know no Mason-Dixon line and opportunity must know no color line,” he told those gathered. “Whatever your views are, we have a Constitution and we have a Bill of Rights, and we have the law of the land, and two-thirds of the Democrats in the Senate voted for it [the civil rights bill] and three-fourths of the Republicans. I signed it, and I am going to enforce it, and . . . any man that is worthy of the high office of president is going to do the same thing.”

All the Way with LBJ

Four weeks later, the nation decided to go “All the Way with LBJ,” voting Johnson into the White House with 61.1 percent of the popular vote. No candidate had made such a sweep since the election of 1820. He also netted 486 electoral votes to Goldwater ’s 52. Of the eight states visited by the Lady Bird Special, Johnson won three—Virginia, North Carolina, and Florida. The other five—South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana—went to Goldwater. The Republicans also claimed Goldwater ’s home state of Arizona.

While a short episode in the acrimonious campaign of 1964, the Lady Bird Special reaped tangible benefits for the Johnson-Humphrey ticket. In her pleasant Southern manner, the first lady had delivered the message that Democrats and her husband hadn’t written off the South over conflicting views regarding civil rights. Democratic leaders who had demurred on endorsing Johnson, because of his stance on civil rights, climbed aboard the Lady Bird Special. The tour mobilized Democratic support in communities that had previously been untapped. It also generated a feel-good story about the Johnson campaign that became fodder for newspapers and nightly newscasts. Reports of Goldwater supporters showing a lack of respect for the first lady didn’t hurt either.

After the election, the first lady and the women who had ridden the Lady Bird Special once again joined forces to promote Head Start, a program aimed at providing an educational and nutritional boost to low-income children.

The Lady Bird Special, which Johnson called “a marvelous, utterly exhausting adventure,” came to hold a special place in her heart. “Scores of times since that October as I have stood in a receiving line someone would come up and say, ‘I rode with you on the Whistlestop’—and we would clasp hands with a warmth and rush of memories of that very special time, those four most dramatic days in my political life.”