You get a sense that it's going to be something other than a blasé afternoon at the museum when the first thing you see is a forty-something man astride a saddle, a Manila hemp lariat in his hand, whooping it up as he tries to rope a wooden—quite stationary—calf on the floor, five feet in front of him. He’s missing, but is clearly under the impression he shouldn’t be, and so keeps trying. That’s a theme of Santa Fe’s New Mexico History Museum’s newest exhibit supported by the New Mexico Humanities Council, “Cowboys Real and Imagined,” which is hands-on, familiar, and full of lessons to be learned.

Ask anyone, almost anywhere in the world, to describe an American and more often than not that description will include a ten-gallon hat, a pair of boots, a six-shooter, and a trusty steed. And while Americans, and particularly those of us living on the great open plains and pastures of the West and Southwest, might focus on different characteristics—toughness, resiliency, and self-sufficiency, a desire for space and a place to mind one’s own business—the cowboy is never far from our hearts.

It’s a love affair that has waxed and waned in these parts for nearly five hundred years. It all began with the Spaniards in the sixteenth century. They brought over the horses, the Arab tradition of leatherworking, and experience from managing livestock on the rolling haciendas of the Iberian Peninsula.

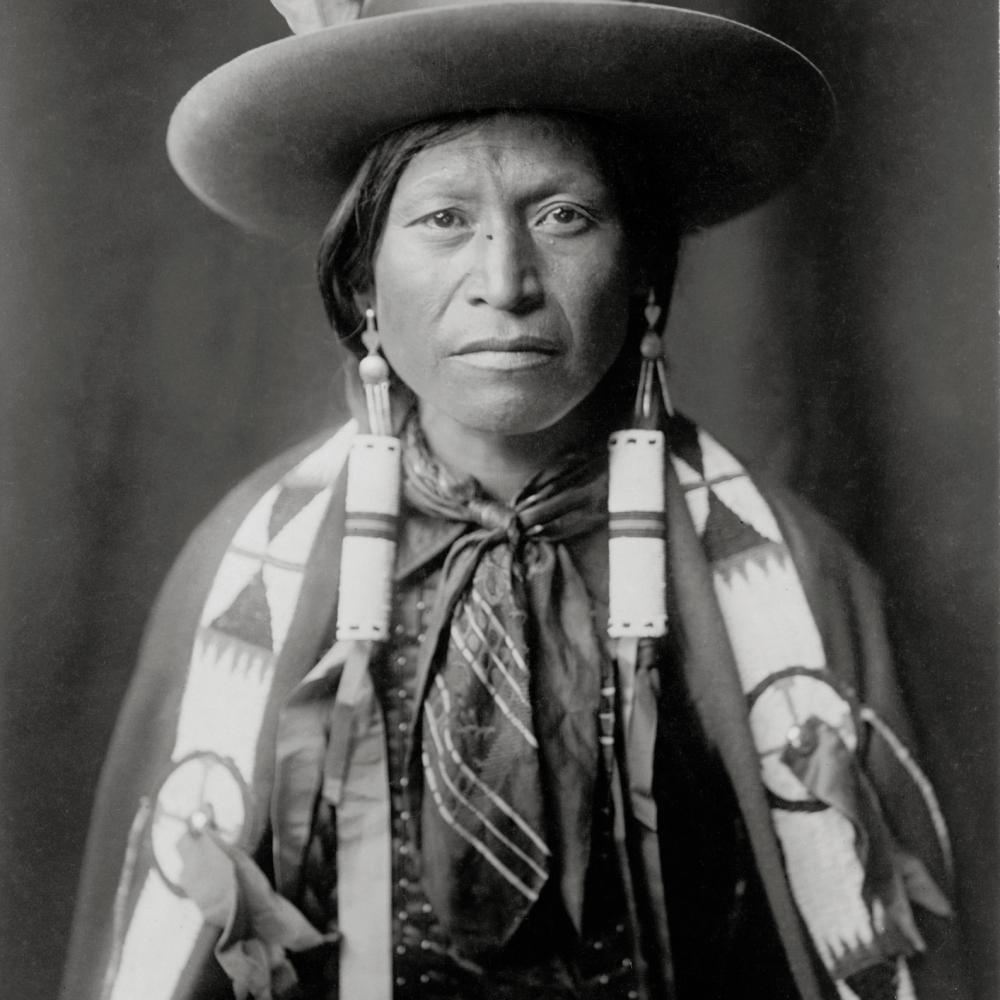

Setting up shop in New Mexico, the vaqueros offered a template of how to dress, how to live, and how to ride. The leather, laconic stoicism, and close bond between man and beast became synonymous with the American cowboy.

By the mid-1800s, vast ranches—with names like Bell, and Diamond A, and Three Block—were home to thou- sands of the vaqueros’ descendants, dedicated to the care and transport of millions of head of cattle. The chuck wagons (yes, there are two in the exhibit), bedrolls, musical instruments, ropes, saddles, and tools of all sorts offer a feel for what that life was like. But none quite as well as Jack Loeffler’s twenty-two-minute soundscape of ranch life with its creaking windmills, snorting cattle, clanking of spurs and tools, and the ever-present sound of wind through the grass.

“One thing that really surprises people is just how short the heyday of the cowboy really was,” says Meredith Davidson, curator of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century Southwest Collection at the museum. And it was—just thirty years or so. As the barbed-wire displays remind us, open range increasingly gave way to fenced land, and a changing job description, one that often included previous unmentionables like farm maintenance. The cowboy ’s reputation sank, and as examples like Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper make clear, the press offered to eager readers stories of debauchery and uncivil behavior.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the cowboy ’s prospects changed again. When Theodore Roosevelt was putting together his Rough Riders brigade for the war in Cuba, he wanted men who could ride and shoot. He found them in what became the “cowboy cavalry.” Wild success in Cuba combined with the publication a few years later of the first critically acclaimed western novel, Owen Wister ’s The Virginian, while the proliferation of art such as Tom Lea’s Winter in New Mexico did much to resuscitate the cow- puncher image.

By the time Buffalo Bill got involved in the wild west show business, and rodeo exploded as a way to show off riding and roping, the cowboy was becoming more make- believe than real. A growing mass media sped it along.

For all of the history and the carefully constructed stories out of New York and Hollywood and Nashville, for every High-Lo Country or The Rounders or Don’t Fence Me In, the West is still a place where the cowboy lives. While Davidson was standing with Jim Keith, a former cowboy and farrier, looking at Robert Lougheed’s famous painting Ten Miles to Saturday Night, the old boy leaned in and said, “Well, shoot, look at that. That’s my saddle.”

And yippie ki-yay? It is a real cowboy term, first used in the nineteenth century. It was reimagined for a 1988 movie staring Bruce Willis.