In 2010, William Richmond Talbot was rummaging in the attic of his Cincinnati, Ohio, home when he came across an old cardboard box tied up with string and marked “Hearthside.” The box had been stored in basements and attics of Talbot family homes for almost a century. Recognizing the name of the house his grandparents had bought north of Providence in 1904, Talbot opened the box. He knew immediately that he had found the kind of treasure attic-rummagers everywhere hope to find. Inside the box were fifty beautiful, perfectly preserved, hand- painted photographs of his family’s legendary house.

As Talbot soon learned, the hand-tinted platinum photographs were taken between 1907 and 1912 by two talented photographers, David Davidson, a well-known commercial photographer in Providence, and Rufus Waterman III, a member of a prominent, old Rhode Island family, but unknown as a photographer.

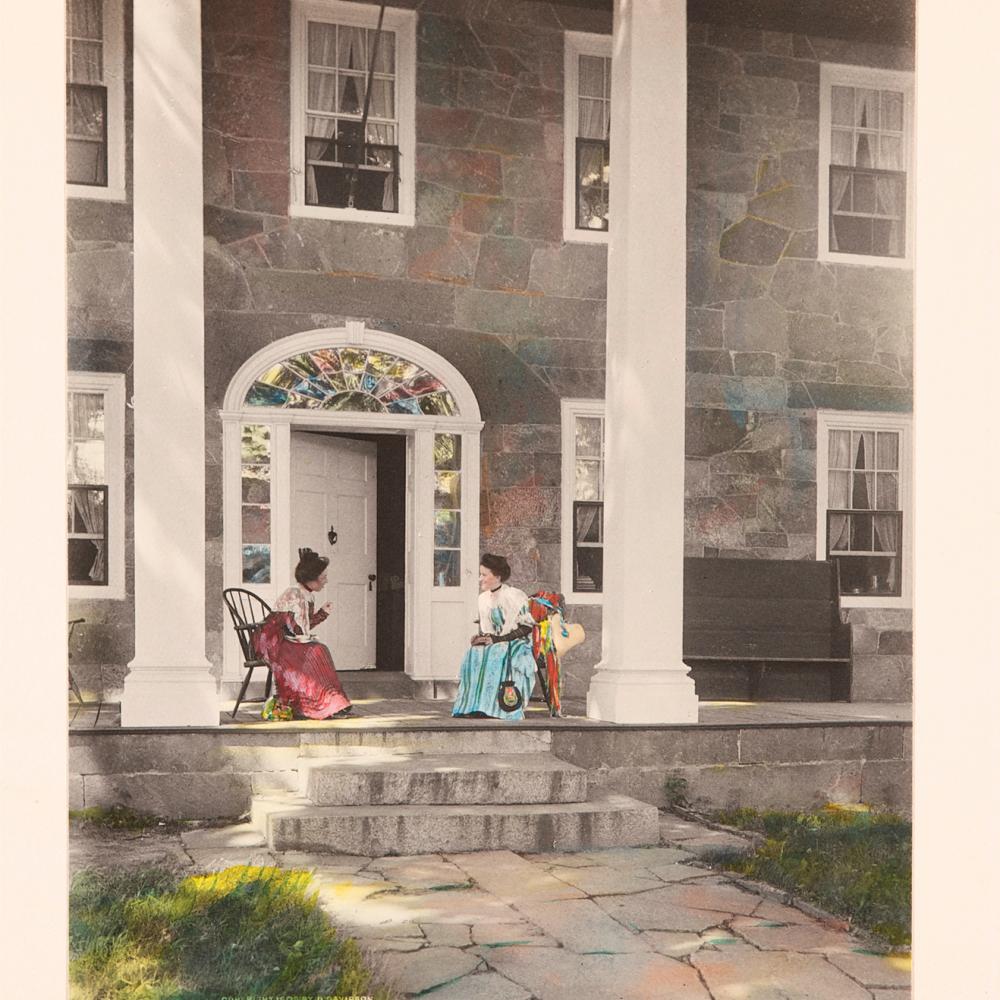

Emulating the hugely popular Wallace Nutting, whose pastoral and colonial scenes decorated the walls of middle- class homes across America, Davidson and Waterman photographed the interior, exterior, and surrounding landscape of the historic house to create vivid colonial vignettes, using their wives and members of the Talbot family, dressed in colonial outfits, as models. Waterman’s photos were hand-tinted by his wife, Alice, while Davidson, like Nutting, employed a staff of low-paid female colorists to painstakingly paint each print.

Bill Talbot gave the precious cache of photographs to the Friends of Hearthside, the organization founded by Kathy Hartley to protect the house after its last private owners sold it to the town of Lincoln in 1996. In July 2012, this passionate group of volunteers organized an exhibition of the Davidson and Waterman photographs in the very rooms in which they were taken more than a hundred years ago. The exhibit, entitled “Color and Light: Early 20th-Century Portraits of Hearthside,” was funded by a grant from the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities and runs through September.

“The history of photography is still a young pursuit, so it is very interesting to have a group of photos like this, images taken in a historic place, come back to where they were taken,” says Jan Howard, curator of prints, drawings, and photographs at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, who advised the Friends of Hearthside.

Lovely in their own right, the Davidson and Waterman photos document Hearthside during the Talbots’ residence. When Arnold and Katharine Talbot bought the “old Smith mansion,” it was already considered historically significant. Built by Stephen Hopkins Smith in 1810, the house is a fine example of early nineteenth-century Federal-style architecture, distinguished by its rare ogee-curve gables. According to legend, Smith built the mansion with $40,000 in lottery winnings for a young woman he was trying to woo. After it was built, she refused to live in it and refused to marry him. The house was chosen as the model for the Rhode Island State Pavilion at the 1904 St. Louis Exposition. In 1937, the house was photographed for the Historic American Buildings Survey, and today it is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

As weavers, the Talbots were invested in the Arts and Crafts movement, which rejected mass production in favor of traditionally made objects. They operated a successful hand-weaving business out of the attic, and began to call the house Hearthside.

Both the Talbots’ lifestyle and the Davidson and Waterman images are expressions of the Colonial Revival movement, says Briann Greenfield, professor of history and coordinator of the public history program at Central Connecticut State University. This nostalgia for a preindustrial era was a response to unsettling social changes—the rapid expansion of cities, the influx of immigrants, changing roles of women, and the growth of an impersonal modern economy.

“There are several ways to understand these photos,” says Thomas Denenberg, director of the Shelburne Museum and a Nutting expert. Hand-painted photographs were, of course, an alternative to color photography before the latter was widely available. But it was also an era when photography was still a new and contested medium, not yet considered art. Hand-tinting the photographs made them look more like watercolor paintings and less like mechanically reproducible prints. “These hand-tinted, soft-focused images were a middle landscape on the way toward a modernist notion of fine art. They were middlebrow art forms for those who could not afford to buy an oil painting,” says Denenberg.

Ironically, this commodified nostalgia was good business. Davidson created more than one thousand titles over the course of his career and sold more hand-tinted photos than any of his contemporaries except his mentor, Nutting, whom he met when Nutting was still the minister of the Union Congregational Church in Providence, before he reinvented himself as a photographer and entrepreneur. Nationally recognized, Davidson won a bronze medal in the category of hand- painted photography at the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco.

“I have most of these pictures in my collection, but I didn’t know where they were taken,” says Michael Pellegrino, an avid collector of Davidson photos. “Knowing the whole story behind them makes them that much more significant.”