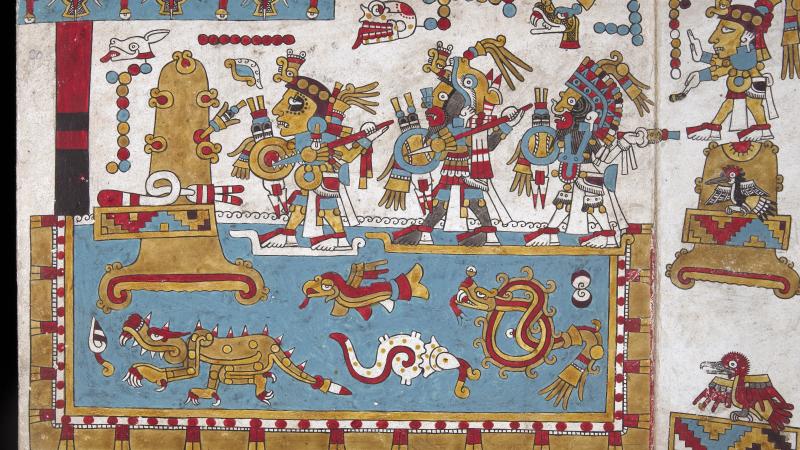

When the curator John Pohl was a teenager building props and sets for the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, he also became obsessed with a very unlikely “storyboard”—the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, a fifteenth-century manuscript in the southern Mexican Mixtec pictographic language that was still in use at the time of the Spanish conquest. One of a handful of pre-Columbian codices to survive the book-burning policies of the Catholic Church, the Codex Nuttall is a remarkable thirty-foot-long, double-sided deer hide accordion scroll covered with intricate, beautiful paintings that tell the adventures of the eleventh-century Oaxaca warrior-king, Lord Eight Deer Jaguar-Claw.

Unlike the then-lost Classic Mayan script, which used syllabic glyphs to represent the phonetics of spoken language, Mixtec is almost entirely pictorial, resulting in a relatively intelligible graphic narrative.

Moving to Los Angeles in the early seventies, Pohl embarked on a unique interdisciplinary education combining archaeology and animation. “I saw it,” he recalls “as the basis for an ideal collaboration between the ancient painter and the contemporary filmmaker. The more I learned about animation, the more I began to detect certain principles in form and design that matched the composition of painted books utilized by the pre-Columbian Mexican civilizations. The emphasis on shortened bodies with enlarged heads and hands, once dismissed by art historians as primitive in design, were exactly what made the earliest Disney characters so effective at communicating basic human emotions cross-culturally, and from longer distances, which made it perfect for courtly settings. So, I started animating these things from the Dover facsimile publication back in the seventies.”

From this idiosyncratic starting point, Pohl has gone on to become one of the most respected scholars of the Postclassic period of Mesoamerican history, the era between the still mysterious collapse of the Classic Mayan empire around 900 CE and the rise to power of the Aztecs and the arrival of the Spanish in the 1500s. But the Codex Nuttall has remained a central obsession. “Unlike many of my colleagues, who were deciphering Mayan writing, I was more interested in why people don’t write. So, I became a specialist in this late Postclassic system, and I’ve spent the thirty-five years of my career not only deciphering this, but actually going out and finding the actual places.”

Pohl’s Nuttall obsession reached a pinnacle recently, when the British Museum agreed to lend the precious manuscript for the first time, as the pivotal artifact in “Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico”—an extraordinary exhibit cocurated by Pohl with Victoria Lyall and the late Virginia Fields of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where it debuted in April before traveling to the Dallas Museum of Art in July.

What loosened the Brits’ grip was the specificity of “Children of the Plumed Serpent,” which was organized, in part, as an alternative to the many surveys of pre-Columbian art and culture that Classic Mayan or conquest-era Aztec periods, ignoring the six centuries in between. During that period, a visually rich but much less centralized culture flourished around the unifying legendary figure of Quetzalcoatl.

Quetzalcoatl is the feathered serpent god who, in human form, was said to have been the king of Tula, a real city north of Mexico City, which—also known as Tollan—served as a sort of Eden in Postclassic mythology. After a rival deity gets him drunk and he commits incest with his sister, Quetzalcoatl is banished and wanders through southern Mexico, where he spreads innovative agricultural and artistic technologies and becomes the patron of many small, independent Nahua, Mixtec, and Zapotec kingdoms in the region in and around modern Oaxaca.

Linked by trade and political marriages, these autonomous kingdoms devoted enormous resources to the production of luxury goods, which were crafted by members of the royal caste. Their trade relationships extended into North America, to the turquoise mines of New Mexico and the Chumash abalone harvests of southern California. As presented in “Children of the Plumed Serpent,” this confederacy of aesthete states constituted a golden age of harmonious politics and unparalleled artistic production that lasted until the Aztecs invaded from the north in 1458.

And it’s hard to argue with the evidence the curators have assembled—more than one hundred and fifty artifacts dating from the tenth century through the Spanish conquest and beyond. Arranged chronologically in five sections, the exhibit opens with a group of architectural fragments from the fabled city of Tula, including a monumental pair of feet from a Toltec warrior column that would have supported the roof of a temple. The Toltec were, appropriately, known as “the people who walked everywhere throughout the world” and it was their peripatetic trade practices and deification of Quetzalcoatl that set the stage for the Postclassic renaissance.

At some distance away, in the northern tip of the Yucatán peninsula, the remnants of the Mayan civilization were gathering in a city called Chichen Itza—and their architecture and cultural artifacts bear a striking similarity to those arising simultaneously among the Toltec. They both embraced Quetzalcoatl, and they shared an eagerness for exotic art supplies, evidenced by the first of several phenomenally intricate turquoise mosaics in the show, a ten-inch diameter mirror frame with a geometric plumed-serpent design recovered from the Castillo Pyramid in Chichen Itza.

Other archaeological finds testify to the expanding visual appetites of the early Postclassic period: cast-gold alloy figurine pendants dredged from the Sacred Cenote or “Well of Sacrifice” in Chichen Itza, but originally produced in what are now Panama or Costa Rica, for example. Or the sudden appearance in both Tula and Chichen Itza (as well as throughout Central America) of plumbate ceramics—the only Mesoamerican pottery to have a highly reflective glaze-like surface—that have been traced to a manufacturing center in the coastal area bordering modern Guatemala and Chiapas. This same region was also responsible for much of the cacao (chocolate) that had a sudden upsurge in popularity at the time, and scholars have posited that the shiny clay vessels were part of an ambitious marketing strategy that reached as far as the American Southwest.

This could account for the narrow range of generic figurative motifs in plumbate—examples here include a bat, a jaguar, a deer, a toad, a turkey, and so on. Even when godlike effigies appear, they are nonspecific, devoid of identifying names or features that would link them to any regional ideological or political tradition. This is arguably ground zero of what was to become known as the International Style not a degeneration of earlier, more sophisticated regional pictographic systems, but a deliberate construction of a transnational graphic vocabulary that could be adapted to the needs of widespread local traditions speaking more than twenty distinct languages.

This new iconographic language is shown coming to fruition in the second section of “Children of the Plumed Serpent,” subtitled “The New Tollan: The Rise of Cholula and the Birth of the International Style.” Around 1200 CE, Quetzalcoatl went through his whole drunken incest banishment episode and headed south, founding a new cult temple in Cholula, a city that exists to this day in the center of the Mexican state of Puebla. In historical terms, this constituted the fall of the city of Tula and a mass migration of Toltecs to Cholula, where a new religious and political center was established, based on relatively egalitarian modes of domination, including control of trade, intermarriage, an elaborate gift economy, and the establishment of Cholula as a site of pilgrimage and religious authority.

Within a hundred years, the new pictographic language had evolved into a sophisticated and widespread lingua franca for most of southern Mexico. Appearing in the elaborate codices and the Nahua-Mixteca polychrome ceramics that superseded plumbate (as well as on various artifacts fashioned from bone, wood, shell, precious metals, and stone), the precise, softly geometric images reduced people, places, things, and actions into easily read, brightly colored cartoons that recounted the creation myths and genealogies that made sense of Quetzalcoatl’s world.

Codices like the Nuttall—arguably one of the greatest works of graphic narrative ever inked—also functioned as a sort of performance script for multimedia storytelling events at the ritual feasts that were a central part of the social life of the new network of independent kingdoms. Almost every artifact included here was, in fact, a sort of theatrical prop. Rather than bash each other’s brains in, rival royals tried to outdo one another with the opulence of their dowries, ceremonial wardrobes, and dinner parties. Artistic production became the driving force behind political decisions—the royal families were the actual artisans, and marriages and households were arranged to maximize aesthetic innovation, quality, and production.

“The artists ruled,” says Pohl. “The artists were in control. Think of a society in which George S. Patton and Frank Lloyd Wright are the same person.”

It is at this point that the culture— and “Children of the Plumed Serpent”—makes an exponential leap in quality and complexity, and the compelling (if convoluted) historical narrative takes a backseat to the utter sensual immediacy of piece after piece of extraordinary craftsmanship and beauty.

Perhaps the single most breathtaking artwork included in the exhibit is the Turquoise-mosaic Disk of Xi- uhtecuhtli (1300–1521) on loan from the Museo del Templo Mayor in Mexico City. Just under sixteen inches wide, the ostensible “shield” is composed from thousands upon thousands of minute, individually shaped fragments of the pale aqueous mineral forming a shifting cubist solar mandala, with intricate International Style representations of the titular sun god cavorting around the perimeter. As with many of the works from the high Postclassic period, the miniature technique involved is mind-bending, especially given that no evidence has surfaced that the artisans of the era had discovered the technology of reading glasses.

They were certainly close though. Another of the most astounding artifacts is a piece of jewelry so small as to almost go unnoticed. At first it appears to be a pair of exquisitely tiny ear studs fashioned from narrow cylinders of gold and jade and inserted in a sleek but perhaps too- modernist display mounting of clear acrylic and dark translucent Bakelite. On close inspection, though, the modernist mounting reveals itself as two further layers of cylindrical earspools—plugs to be inserted in expanded earlobes—meticulously ground from black obsidian and lens-clear rock crystal. How long must this have taken? Ancient astronauts were clearly involved.

This bountiful gift economy operated for centuries until the Aztec empire conquered the south and repurposed the palace ateliers to their own military- industrial ends. The final sections of “Children of the Plumed Serpent” demonstrate how this flexible, cell-based society adapted first to their aggressive northern neighbors, and immediately thereafter to the game-changing arrival of the Spanish conquistadors and Catholic missionaries. A pairing of objects toward theend of the exhibit makes a powerful and poetic demonstration of the resiliency of the Quetzalcoatlian iconography: A carved basalt monument of a coiled plumed serpent is paired with an identical sculpture that has been flipped over, decapitated, and carved out to transform it into a baptismal font.

The members of the southern confederacy were, in fact, the foot soldiers that made the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs possible, and afterward they teamed with the Franciscan and Dominican authorities to oust the military occupation government in favor of a trade-based economy much like the one that had supported them for six hundred years, and which allowed many of the ancient traditions to continue, even to the present day. A video projected in the final gallery documents the contemporary Festival of the Virgin of the Remedies in Cholula—a thinly repackaged festival of Quetzalcoatl, where up to 350,000 indigenous people from southern Mexico gather every September to celebrate their community and trade rare goods.

By emphasizing the International Style of pictographic language as epitomized by the Codex Nuttall, John Pohl and his colleagues have deliberately shifted the emphasis from a linear verbal mode of comprehending the world to a synoptic visual mode that speaks of the timeless and species-wide power of visual art. The surprisingly optimistic coda states that, in a world where there’s alwaysa bigger bully just down the road, it’s the ability to create—to channel the feathered serpent—that allows a culture to survive, evolve, and prosper.