Ever since Bram Stoker unleashed Dracula on readers in 1897, the undead have been stalking literary and pop culture with abandon. At first it was a slow trickle, as others imitated Stoker on the page, but once Hollywood sank its teeth into vampire mythology, it couldn’t quit feeding. In the past six months alone, an army of vampires has appeared on the big screen.

Johnny Depp and Tim Burton, diehard Dark Shadows fans, resuscitated two-hundred-year-old vampire Barnabas Collins and his dysfunctional family from the 1960s TV show. In Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, the president stops the vampire-led Confederacy from destroying the Union. Then there was the return of True Blood, HBO’s Southern Gothic gore fest, which features a love triangle between perky waitress Sookie and her vampire suitors, Bill and Eric. And, this November, tens of thousands of young girls and their mothers will be lining up for midnight showings of the final movie in Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight series.

If Stoker climbed out of his grave, he would probably be surprised at the pantheon of vampires his book has sired and the fandom that has evolved around them. In his day, there weren’t fans declaring their allegiance to characters with “Team Dracula” or “Team Harker” T-shirts as they’ve done with Twilight and True Blood. Nor were there websites and message boards where you could check for the latest news about your sparkly vampire crush 24/7.

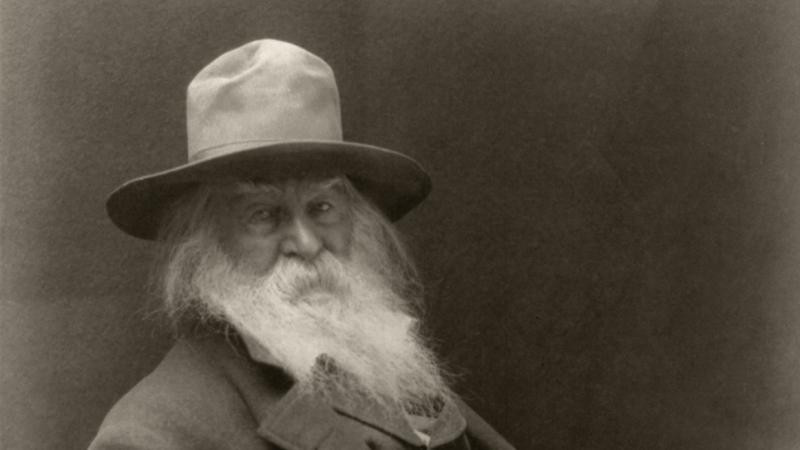

But Stoker wasn’t immune to the lure of fandom. He understood it very well. The object of his adoration wasn’t a bloodsucking creature of the night, but an aging American poet who had scandalized America. When he was twenty-two, Stoker read and fell in love with Walt Whitman’s poetry, finding solace and joy between the covers of Leaves of Grass.And, like many fans, he wanted the connection that he felt to Whitman to be real. Late one night, cloaked in the comfort of darkness, Stoker poured his soul out to Whitman in a shockingly honest letter that described himself and his disposition. That letter, when Stoker finally mustered the courage to mail it, would begin an unexpected literary friendship that lasted until Whitman’s death.

The Fan

The Bram Stoker who put pen to paper was a young man who had, in the previous decade, grown from a sickly boy into a brawny athlete. Born on November 8, 1847, he was the third of seven children to Charlotte and Abraham Stoker. “In my babyhood I used, I understand, to be often at the point of death,” writes Stoker in his memoir. “Certainly till I was about seven years old I never knew what it was to stand upright.” His earliest memories were of being carried somewhere—to the couch, to the bed, to a patch of grass outside. Decades later, Stoker suggested that his illness, the nature of which still remains a mystery, helped foster his interest in writing. “I was naturally thoughtful and the leisure of long illness gave opportunity for many thoughts which were fruitful according to their kind in later years.”

The Stokers lived in a modest three-story Georgian house on 15 Marino Crescent in Clontarf, a pleasant coastal suburb of Dublin, known as the site of King Brian Boru’s victory over the Vikings in 1014. While Stoker’s father reported for his civil service clerkship at Dublin Castle, the seat of British rule in Ireland, his mother saw to his education. At age twelve, he began studying part of the day with Reverend William Woods, who oversaw a small prep school. Along with mastering classics and mathematics, Stoker focused on improving his health and endurance. The young boy who had to be carried everywhere gradually turned into a tall, strapping lad who relished long walks and anything athletic in nature.

In 1864, Stoker headed to Trinity College, Ireland’s top university and a bastion of Protestantism. His transformation continued, as he used his physicality to “overcome my natural shyness.” Having grown to be the tallest in his family, he became University Athlete in 1867, winning awards for weight-lifting and endurance walking. And Stoker wasn’t just formidable on the rugby pitch. He became a fierce debater, honing his skills as a member of the University Philosophical Society, Trinity’s most prestigious club, and the College Historical Society. He also scored solid marks in his courses, earning a degree in science in 1871, followed by master’s work in mathematics.

Reading Walt

By his own recollection, Stoker’s first encounter with Walt Whitman was in a book review. The October 1869 edition of the Temple Bar: A London Magazine for Town and Country Readers featured a blistering appraisal of Poems by Walt Whitman. The reviewer took issue with Whitman constantly inserting himself into his work. He declared Whitman’s rendering of his four themes—America, democracy, personality, and materialism—shallow. “Unable, just like many of his somewhat less boisterous contemporaries, to understand the vast problem presented by the past, present, and future of the world, like them again he fancies he has solved it by a clumsy application of the bene quodcunque est [say nice things about everything] doctrine.” The reviewer also found Whitman’s description of bodies distasteful and his style appalling. “His style has nothing in common with either the Bible, Shakspeare, Plato, or any other hitherto honoured name in literature; but that his grotesque, ungrammatical, and repulsive rhapsodies can be fitly compared only to the painful ravings of maniacs’ dens.” To close, the reviewer tossed in an anti-American zinger. “It has been said of Mr. Whitman by one of his warmest admirers, ‘He is Democracy.’ We really think he is—in his compositions, at least; being, like it, ignorant, sanguine, noisy, coarse, and chaotic!”

Poems by Walt Whitman, published in 1868, was the first British printing of Whitman’s work. Until then, if you wanted to read Whitman you had to find someone to lend you one of the few copies of Leaves of Grass that had made its way across the Atlantic or you had to know someone in America who could send you a volume. British publishers refused to undertake a British edition, afraid of running afoul of Victorian-era pornography laws.

There were those, however, who felt Whitman needed to be read by a wider audience, among them William Michael Rossetti, brother to Dante and Christina and a leading force in the pre-Raphaelite movement. After being given an 1867 edition of Leaves of Grass by a friend, Rossetti fell hard for Whitman, whom he regarded as “the most sonorous poetic voice of the tangibilities of actual and prospective democracy.” The problem was how to bring this voice of democracy to the British reading public. Rossetti’s solution was to cut Leaves of Grass in half. “Whitman, though resigned, is not really pleased at the publication of a mere selection of his poems,” wrote Rossetti in his diary in November 1867.

Rossetti’s edition featured a twenty-seven-page introduction, which crowned Whitman as the founder of American poetry and laid out the rationale for the poems selected. “My choice has proceeded upon two simple rules: first, to omit entirely every poem which could with any tolerable fairness be deemed offensive to the feelings of morals or propriety in this peculiarly nervous age; and, second, to include every remaining poem which appeared to me of conspicuous beauty or interest.” Whitman’s preface to the 1867 edition was scrubbed of objectionable language. Aware of the Eurocentric tastes of his circle, Rossetti added epigraphs by Michelangelo, Thomas Carlyle, Emanuel Swedenborg, and Maximilien Robespierre.

It was this bastardized volume and review—not Leaves of Grass—that set Stoker and his literary friends talking and laughing at Whitman’s expense. “Needless to say that amongst young men the objectionable passages were searched for and more noxious ones expected,” wrote Stoker.

More than a year after the review appeared, however, Stoker had a conversion. While listening to two college chums read out loud lines of Whitman’s poetry and mock them, he began to wonder if he had judged Whitman hastily. Not long after, he accepted a copy of Leaves from a man he encountered in Trinity Quad who was eager to part with it. “I took the book with me into the Park and in the shade of an elm tree began to read it. Very shortly my own opinion began to form; it was diametrically opposed to what I had been hearing. From that hour I became a lover of Walt Whitman.”

Midnight Confession

After falling for Whitman, Stoker wasn’t shy about promoting the merits of his work, even standing up for him in a debate of Trinity’s Philosophical Society. The fan, however, longed for a closer relationship. On the night of February 18, 1872, he wrote a letter to Whitman that ran nearly two thousand words.

Stoker opened by telling Whitman that he could burn the letter, but hoped that he would resist. “I don’t think there is a man living, even you who are above the prejudices of the class of small-minded men, who wouldn’t like to get a letter from a younger man, a stranger, across the world—a man living in an atmosphere prejudiced to the truths you sing and your manner of singing them.” He greatly valued Whitman’s candor, regarding him as different from other men, and hoped that they could be friends. “If I were before your face I would like to shake hands with you, for I feel that I would like you. I would like to call you Comrade and to talk to you as men who are not poets do not often talk.” Stoker then declared Whitman to be a “true man,” confessing that he yearned to be one himself, “and so I would be towards you as a brother and as a pupil to his master.”

Having made his admiration known, Stoker described his life: He was twenty-four years old, named after his father; his friends called him Bram, and he earned a small salary working as a clerk for the government. Next came his person and demeanor:

I am six feet two inches high and twelve stone weight naked and used to be forty-one or forty-two inches round the chest. I am ugly but strong and determined and have a large bump over my eyebrows. I have a heavy jaw and a big mouth and thick lips—sensitive nostrils—a snubnose and straight hair. I am equal in temper and cool in disposition and have a large amount of self control and am naturally secretive to the world. I take a delight in letting people I don’t like— people of mean or cruel or sneaking or cowardly disposition—see the worst side of me.

Stoker included his physical description, because he surmised from Whitman’s works and his photograph that he would be interested to know the “personal appearance of your correspondents.” Wrote Stoker: “You are I know a keen physiognomist.”

Stoker attempted to convey what Whitman’s poetry meant to him. “I have to thank you for many happy hours, for I have read your poems with my door locked late at night, and I have read them on the seashore where I could look all round me and see no more sign of human life than the ships out at sea: and here I often found myself waking up from a reverie with the book lying open before me.” Whitman’s verse had been life-changing for a self- confessed conservative from a conservative country. “But be assured of this, Walt Whitman—that a man . . . who has always heard your name cried down by the great mass of people who mention it, here felt his heart leap towards you across the Atlantic and his soul swelling at the words or rather the thoughts.”

Stoker closed by acknowledging his frankness. “I have been more candid with you—have said more about myself to you than I have ever said to any one before. You will not be angry with me if you have read so far. You will not laugh at me for writing this to you. It was with no small effort that I began to write and I feel reluctant to stop, but I must not tire you any more.”

What seemed so urgent and pure in the middle of the night must have seemed rash and confessional in the daylight. Stoker didn’t send the letter. Instead, he tucked it inside his desk drawer.

Over the next few years, Stoker continued to debate Whitman’s poetry with his friends. While still working as a clerk, he began to slowly make a name for himself as a drama critic. When Stoker was a young boy, his father would return from the theater and regale him with vivid descriptions of what he had seen: an exotic set, an actor who overreached, an actress who cried convincingly, a detailed summary of the plot. When he was older, Stoker joined his father on theater outings and dabbled a bit in acting. Unhappy with how Dublin newspapers covered theater—staff reporters with no expertise were often assigned to write reviews—Stoker approached the owner of the Mail about covering plays. Upon being told that there was no extra money for critics, Stoker offered to write for free, launching his career in criticism. “I was thus able to direct public attention, so far as my paper could effect it, where in my mind such was required,” he wrote.

Along with theater reviews, Stoker published short stories, placing his first one in London Society in 1872. “It was a good time for short story writers with something to say; but Stoker, still edging toward maturity, kept recycling hackneyed plots and themes. No one would have called him an original writer,” writes Barbara Belford in Bram Stoker, her NEH-supported biography. Three years would pass before he struck again. In spring 1875, The Shamrock serialized three of his stories, all of which traded in romance and villainy.

On Valentine’s Day of 1876, Stoker found himself once more defending Whitman. This time it was during a meeting of the Fortnightly Club, which was known for its free- wheeling debates. A man of “some standing socially” with a good university record challenged Whitman’s collection of poems on the grounds that it lacked “mention of one decent woman.” To Stoker’s mind he went “too far,” because “Walt Whitman honoured women.”

That night, before he went to bed, Stoker once again wrote to Whitman, expressing his admiration. “The stress of the evening had given me courage,” he wrote in his memoir. Along with the new letter, he included the one that sat in his desk drawer. “It speaks for itself and needs no comment,” Stoker told Whitman. “It is as truly what I wanted to say as that light is light. The four years which have elapsed have made me love your work fourfold, and I can truly say that I have ever spoken as your friend.” He also expressed his wish that he might some day meet Whitman in Ireland.

Three weeks later, a letter addressed to Stoker in the poet’s distinctive spidery hand appeared in his mailbox. Whitman thanked him for his letters, both as a person and as an author. “You did well to write me so unconventionally, so fresh, so manly, and so affectionately, too. I too hope (though it is not probable) that we shall one day meet each other. Meantime I send you my friendship and thanks.”

Years later, Whitman shared the exchange of letters with his friend Horace Traubel, who recorded their conversation in With Walt Whitman in Camden. “He was a sassy youngster,” Whitman said of Stoker. “[A]s to burning the epistle up or not—it never occurred to me to do anything at all: what the hell did I care whether he was pertinent or impertinent? he was fresh, breezy, Irish: that was the price paid for admission—and enough: he was welcome!” Whitman had also noticed that Stoker had written more to himself than to the poet. “I could not but warmly respond to that which is actually personal: I do it with my whole heart.”

The Poet Who Inspired Multitudes

The Walt Whitman who wrote Stoker was almost sixty years and declining in health. “My physique is entirely shattered—doubtless permanently, from paralysis and other ailments,” Whitman told Stoker. “But I am up dressed, and get out every day a little.” The poet had suffered the first in a series of strokes in 1873, leaving his left arm and leg frail. That same year, he moved to Camden, New Jersey, where his brother owned a pipe-manufacturing business. Camden didn’t have the bustle of his beloved Brooklyn or wartime Washington, D.C., but it was situated across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, an easy trek for Whitman’s fans—and by the 1870s, they were legion.

Whitman had been a typesetter, printer, teacher, and newspaper man leading up to the publication of Leaves of Grass in 1855. For years, he had scribbled lines of poetry and observations about what he saw while roaming the streets of New York, most of it unremarkable in style and form. In the late 1840s, Whitman began to trade conventional poetic structure for something looser and more innovative. Whitman scholars have tried to explain the reason for the dramatic shift, speculating that it might have been fueled by a religious experience or the poet’s decision to embrace his homosexuality. Whitman, however, may have supplied the answer when he said a poet ought to “flood himself with the immediate age as with vast oceanic tides.” Another factor was reading Ralph Waldo Emerson. “I was simmering, simmering, simmering; Emerson brought me to a boil,” he told John Townsend Trowbridge.

David Reynolds, Whitman’s biographer, calls Leaves “a dazzling literary potpourri.” “Under one poetic roof he gathered together disparate images from nature, city life, oratory, the performing arts, science, religion, and sexual mores,” writes Reynolds. Reviewers of the time didn’t share his enthusiasm, registering polite interest or outright disdain for the book’s sexual content and Whitman’s ego. “There is neither wit nor method in his disjointed babbling, and it seems to us he must be some escaped lunatic, raving in pitiable delirium,” wrote the Boston Intelligencer. Whitman, however, could take heart that Emerson, to whom he sent a copy, felt differently. “I rubbed my eyes a little, to see if this sunbeam were no illusion; but the solid sense of the book is a sober certainty,” Emerson wrote Whitman.

Leaves was hardly a best-seller, prompting Whitman to tinker with its composition. The 1856 edition grew from twelve to thirty-two poems, and each poem had a title, something the first edition lacked. Whitman also included Emerson’s letter praising him, much to Emerson’s consternation and his own benefit. People started to take notice. Not long after the second edition appeared, Bronson Alcott, a leading transcendentalist and father to Louisa May, called on Whitman. He returned for another visit, bringing with him Sarah Tyndale, a prominent abolitionist, and Henry David Thoreau. Alcott wrote that Whitman and Thoreau had eyed each other “like two beasts, each wondering what the other would do, whether to snap or run.” Nevertheless, Thoreau continued to call.

The Civil War boosted Whitman’s reputation, both as a man and as a poet. During the war, Whitman tended to more than tens of thousands of soldiers in hospitals around Washington, D.C., earning him the nickname “the Good Gray Poet.” In January 1865, he landed a job at the Department of Indian Affairs, but found himself fired a few months later. The oft-told story is that James Harlan, the secretary of the interior, objected to having the author of a “dirty book” on staff. For the 1860 edition of Leaves, Whitman had added one hundred forty-six poems and arranged them in thematic clusters. The “Calamus” cluster, which explored romantic friendships between men, pushed the conventions of the era and made men like Harlan uncomfortable.

Whitman’s dismissal turned out to be a bit of luck—at least in the grand scheme of author adulation. The day after he was fired, Whitman landed a job as a clerk in the attorney general’s office with the help of his friend William Douglas O’Connor. Outraged by Harlan’s actions, O’Connor wrote a forty-six-page pamphlet, The Good Gray Poet: A Vindication (1866), which painted a larger-than-life portrait of Whitman. A year later, John Burroughs, a young aspiring author, wrote Notes on Walt Whitman, a somewhat hagiographic account of Whitman’s life and work. Like Stoker, Burroughs had his own conversion experience while reading Leaves of Grass; in his case, a friend shared poems from the volume during a walk in the woods. The title page of the book lists Burroughs as the author, but Whitman played a major role in shaping its content.

Whitman’s fame was further enhanced by the publication in 1865 of Drum-Taps, a collection of forty-three poems that chronicle his evolving physical and spiritual experience with the Civil War. The poet originally believed that the war could not be captured in verse, but gradually changed his mind as the sights and smells of battle and death made their impression. Following Lincoln’s assassination, Whitman published Sequel to Drum-Taps, which included additional poems, four specifically about Lincoln, whom he idolized. “O Captain! My Captain!,” which mourns the death of the president, became Whitman’s most recognized poem during his lifetime.

As the 1870s dawned, Whitman’s fan base continued to grow, aided by the efforts of O’Connor, Burroughs, and others. “Whitman basked in his disciples’ attention,” writes Michael Robertson in the NEH-supported Worshipping Walt: The Whitman Disciples. “Leaves of Grass never won a wide audience during his lifetime, and it produced only a modest income. In compensation, however, it brought [Whitman] ardent followers.”

Fan letters filled his mailbox. Reading them helped ease the loneliness Whitman felt since moving to Camden and the limitations imposed by his stroke. He could no longer amble through a neighborhood or roam a city, soaking up its sights and sounds, as had been his custom from a young age. His fans bought copies of each new edition of Leaves (you can see all seven editions online at the NEH-supported Walt Whitman Archive) and supported him when he got into trouble. They came to Whitman’s defense when he stirred up a transatlantic war of words in 1876 after writing a mischievous essay for a British journal claiming—with some exaggeration—that he had been neglected by his American literary peers. They would also rally around him in 1881 when the Boston district attorney attempted to ban the publication of a new edition of Leaves on the grounds that it was obscene.

The Other Man in Stoker’s Life

In Stoker’s confessional letter, he wrote that he hoped to meet Whitman someday soon. “Shelley wrote to William Godwin and they became friends. I am not Shelley and you are not Godwin and so I will only hope that sometime I may meet you face to face and perhaps shake hands with you. If I ever do it will be one of the greatest pleasures of my life.” Whitman’s health foiled plans to bring him to England and Ireland. Ironically, it would be the other man in Stoker’s life, Henry Irving, who would finally allow Stoker to realize his dream.

Stoker’s career took a sharp turn when Irving, the most famous actor in England, asked him to manage London’s Lyceum Theatre in 1878. Stoker had been enchanted with Irving from the moment he first saw him take the stage in an 1867 production of The Rivals. Writing of the night forty years later, Stoker could still recall Irving’s movements, expression, and tone of voice. “What I saw, to my amazement and delight, was a patrician figure as real as the persons of one’s dreams, and endowed with the same poetic grace. A young soldier, handsome, distinguished, self-dependent, compact of grace and slumberous energy.”

There was something in Stoker’s makeup that disposed him to adulation—to being a hardcore fan—and he intently followed Irving’s career. The lack of press coverage given to Irving’s 1871 turn in Two Roses inspired Stoker’s decision to become a drama critic. When Irving brought his legendary production of Hamlet to Dublin in December 1876, Stoker was in the audience for three performances. A glowing review followed, and Irving, taken with Stoker’s appreciation for what he was trying to accomplish with the petulant Danish prince, invited Stoker to dine with him in his suite at the Shelbourne Hotel. They talked long into the night, aided by a bit of alcohol and a mutual love of the theater. Irving recited Thomas Hood’s “The Dream of Eugene Aram,” even collapsing into a brief faint at the end. “That experience I shall never—can never—forget,” wrote Stoker. “The recitation was different, both in kind and degree, from anything I had ever heard.”

The friendship forged that night would expand each time Irving returned to Dublin. In quiet moments between rehearsals and boozy dinners, the men discussed Irving’s dream of having his own theater and what it would take to realize it. In November 1878, Irving telegraphed Stoker and asked him to come to Glasgow; Stoker arrived the following evening. “He told me that he had arranged to take the management of the Lyceum into his own hands,” writes Stoker. “He asked me if I would give up the Civil Service and join him; I to take charge of his business as Acting Manager.” Stoker’s answer was an unequivocal “yes.”

Working for Irving meant moving to London, but Stoker did not start this new chapter in his life alone. In December 1878, Stoker, then thirty-one years old, married Florence Balcombe, the nineteen-year-old daughter of an army colonel. Balcombe is famous in literary annals for having been the object of a serious crush by Oscar Wilde, who took the news of her marriage to Stoker hard. Unfortunately, neither Stoker nor Balcombe left behind any clues as to the nature of their courtship or even how they met.

While Irving dreamed up new productions and terrorized the cast with his outsized ego, Stoker attended to his business affairs. The partnership lasted for twenty-five years and profoundly shaped Stoker’s life. Irving possessed a domineering personality, and Stoker was beholden to him. The extent to which Stoker defined himself in terms of Irving can be seen in the Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving, a two-volume account of Stoker’s relationship with the actor that is part memoir, part celebrity worship.

But working for Irving and being at the epicenter of London’s theater culture did have some benefits. He was part of London’s literati, socializing with Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle—and even Wilde, once the playwright forgave him. Stoker developed relationships with British literary journals and publishers that were receptive to his fiction. He also had the opportunity to travel to the United States, the country of Whitman and his democratic ideals. When Irving decided to bring the Lyceum Theatre to American audiences, the tour required transporting a large cast of players, lavish sets, and voluminous costumes—and Stoker made all the arrangements.

Meeting His Idol

In March 1884, the Lyceum tour stopped in Philadelphia, making it possible for Stoker finally to meet his literary idol. Stoker envisioned slipping away to call on his hero, but when Irving found out about his plan he asked to come along. Irving was a casual fan at best, but he couldn’t pass up the chance to meet the famous Walt Whitman. On the afternoon of March 20, they called at the house of Thomas Donaldson, one of Whitman’s friends and benefactors. Like many in the poet’s circle, Donaldson wrote a memoir of their friendship, Walt Whitman: The Man (1896), which gives us another account of the meeting.

They found the poet sitting in Donaldson’s parlor. “On the opposite side of the room sat an old man of leonine appearance,” wrote Stoker. “He was burly, with a large head and high forehead slightly bald. Great shaggy masses of grey-white hair fell over his collar. His moustache was large and thick and fell over his mouth so as to mingle with the top of the mass of the bushy flowing beard.” Donaldson introduced Irving first, then Stoker. Whitman leaned forward in his chair and held out his hand. “Bram Stoker—Abraham Stoker is it?” Stoker said yes and they shook hands as two old friends. Stoker would have to wait to speak to Whitman, as the honor of one-on-one conversation fell first to Irving. The poet and actor talked for “a good while and seemed to take to each other mightily.” Irving ventured that Whitman reminded him of Tennyson, a comparison the poet heartily embraced. For his part, Whitman was struck by Irving’s demeanor—“his gentle and unaffected manners and his evident intellectual power and heart.”

When Stoker finally got his chance, Whitman did not disappoint. “I found him all that I had ever dreamed of, or wished for in him: large-minded, broad-viewed, tolerant to the last degree; incarnate sympathy; understanding with an insight that seemed more than human.” They spoke as old friends and traded gossip about mutual acquaintances in Dublin. “Before we parted he asked me to come see him at his home in Camden whenever I could manage it. Need I say that I promised.” Whitman found much to like about Stoker too, calling him “an adroit lad.” “He’s like a breath of good, healthy, breezy sea air,” he told Donaldson.

Two years passed before Stoker could make the trip to Camden. In the fall of 1886, he traveled to New York to make arrangements for the Lyceum’s forthcoming tour of Faust. On November 2, he took the train down to Philadelphia and met up with Donaldson, who accompanied him on the visit. Whitman’s house at 328 Mickle Street was “a small ordinary one in a row, built of the usual fine red brick which marks Philadelphia and gives it an appearance so peculiarly Dutch.” They arrived to find Whitman sitting in a big rocking chair that had been a gift from Donaldson’s children. “He seemed feebler, and when he rose from his chair or moved about the room did so with difficulty. I could notice his eyes better now. They were not so quick and searching as before.”

Whitman’s mind remained sharp, and their conversation roamed from London literary gossip to Irving’s latest stage triumphs to Abraham Lincoln. When Stoker confessed his admiration for Lincoln, Whitman declared, “No one will ever know the real Abraham Lincoln or his place in history!” Stoker asked Whitman about his “startlingly vivid” account of Lincoln’s assassination at the hands of John Wilkes Booth. The essay had been published in Specimen Days, the poet’s autobiography. Whitman said that while he hadn’t been present when the president was shot, he had “spent the better part of the night interviewing many of those who were present.” Whitman’s account was pure fiction—he had been in New York at the time of the assassination. But Stoker was captivated. “The memory of that room will never leave me,” he wrote.

Stoker’s conversation with Whitman ended up playing a starring role in a lecture he had started writing and would deliver at the London Institution. Stoker incorporated Whitman’s proclamation—significantly embellished—into the lecture: “Not long since Walt Whitman said to me: ‘No man knows—no one in the future can ever know Abraham Lincoln. He was much greater—so much vaster even than his surroundings—what is not known of him is so much more than what is, that the true man can never be known on earth.’”

Stoker had one last meeting with Whitman in December 1887, when the Lyceum Theatre ventured to the United States for another tour. Once again, he met up with Donaldson to make the pilgrimage to Mickle Street, where he found Whitman “hale and well.” “His hair was more snowy white than ever and more picturesque. He looked like King Lear in Ford Madox Brown’s picture,” wrote Stoker.

After the old friends exchanged affectionate greetings, Stoker broached with Whitman a subject of some delicacy: editing some of his poems. Stoker had been discussing the idea with their mutual friend Talcott Williams, editor of the Philadelphia Press. If Whitman would let them cut about one hundred lines his books could go into every house in America. “Is that not worth the sacrifice?” asked Stoker. Whitman gave a swift retort, according to Stoker:

“It would not be any sacrifice. So far as I am concerned they might cut a thousand. It is not that—it is quite another matter:”—here both face and voice grew rather solemn—“when I wrote as I did I thought I was doing right and right makes for good. I think so still. I think that all that God made is for good—that the work of His hands is clean in all ways if used as He intended! If I was wrong I have done harm. And for that I deserve to be punished by being forgotten! It has been and cannot not-be. No, I shall never cut a line so long as I live!”

Despite the tense discussion, Whitman and Stoker parted friends. Whitman even sent Stoker off with a keepsake: an autographed 1872 edition of Leaves of Grass and a photograph of himself.

“That was the last time that I ever saw the man who for nearly twenty years had held my heart as a dear friend,” wrote Stoker. Whitman passed away in March of 1892, his body finally giving out after a bout of pneumonia. When Stoker passed through Philadelphia in 1894, he was shocked to learn that Whitman had left something for him in Donaldson’s care: the original notes from the lecture Whitman gave about Lincoln at the Chestnut Street Opera House on April 15, 1886.

“This was my Message from the Dead,” wrote Stoker.

The Undead

During the summer of 1896, while tucked away at the Kilmarnock Arms Hotel in Cruden Bay, Scotland, Stoker put the finishing touches on Dracula. Unlike his other stories and novels, which he tended to whip out, he’d worked on Dracula for seven years, shaping and reshaping the characters, along with the book’s epistolary structure. “The novel’s genesis was a process, which involved Stoker’s education and interests, his fears and fantasies, as well as those of his Victorian colleagues. He dumped the signposts of his life into a supernatural cauldron and called it Dracula,” wrote Belford. What emerged was the story of Jonathan Harker, a novice solicitor, who does battle with the nefarious vampire Count Dracula in Transylvania and London. Aiding Harker in his fight are the mysterious Dr. Abraham Van Helsing, Lord Godalming, Texas gunfighter Quincey Morris, and Dr. John Seward. Together they rescue Mina, Harker’s fiancée who has fallen victim to the vampire, and kill Dracula.

Stoker wasn’t the first to write about vampires. Folktales about bloodsucking creatures of the night had been kicking around Europe for centuries and were slowly making their way into popular culture. In 1819, John Polidori, Lord Byron’s doctor, published the first vampire tale in English in New Monthly Magazine. The story originated out of the same challenge issued on a summer’s eve in 1816 that led Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley to write Frankenstein. A few decades later, Varney the Vampire, heavy on the gothic and gore, appeared in the penny dreadfuls between 1845 and 1847. The 667,000-word serialized tale of Sir Francis Varney’s campaign of terror against the Bannerworth family introduced many of the traits we’ve come to associate with vampires, including puncture wounds and superhuman strength. Stoker’s vampire tale, however, was something different. While grounded in gothic horror and romance—two of Stoker’s favorite themes—it also channeled the mores and anxieties of British society at the close of the nineteenth century.

Dracula debuted in the spring of 1897 to mixed reviews. The Daily Mail declared that “the recollection of his weird and ghostly tale will doubtless haunt us for some time to come.” Athenaeum had reservations: “‘Dracula’ is highly sensational, but it is wanting in the constructive art as well as in the higher literary sense.” The Spectator thought that while Stoker made admirable use of “vampirology,” the story might have been better had it been set in an earlier period. “The up-to-dateness of the book—the phonograph, diaries, typewriters, and so on—hardly fits in with the mediaeval methods which ultimately secure the victory for Count Dracula’s foes.” (Spoiler alert: Dracula is killed by a bowie knife to the heart.)

Dracula was a minor publishing success. The first print run was a modest three thousand copies and a paperback edition didn’t appear until 1901. It took two years and serialization in the New York Sun and other newspapers before Doubleday & McClure printed an American edition in 1899. The modest sales, however, helped Stoker make a name for himself as an author on both sides of the Atlantic. He even got an entry in Who’s Who.

Given Stoker’s hero worship of Whitman, literary scholars have looked for evidence of the poet’s influence on Dracula. A cryptful of critics spent the late 1980s and 1990s fixating on the novel’s morbid sensuality and what it suggested about homosexuality. It was on this issue that they frequently located Whitman’s fingerprints. Belford regards Whitman’s influence as “profound,” noting that the Count and Whitman share common physical traits. “Each has long white hair, a heavy moustache, great height and strength, and a leonine bearing. Whitman’s poetry celebrates the voluptuousness of death and the deathlike quality of love.”

Stoker didn’t leave any explicit clues behind to suggest whom he had modeled Count Dracula on. But given that Whitman wasn’t averse to a little hero worship, he might have liked being turned into an immortal creature with a lustful fan base.

When Stoker died in 1912, Sotheby’s auctioned off his library. Whitman’s lecture on Lincoln, which he bequeathed to Stoker, sold for $25.