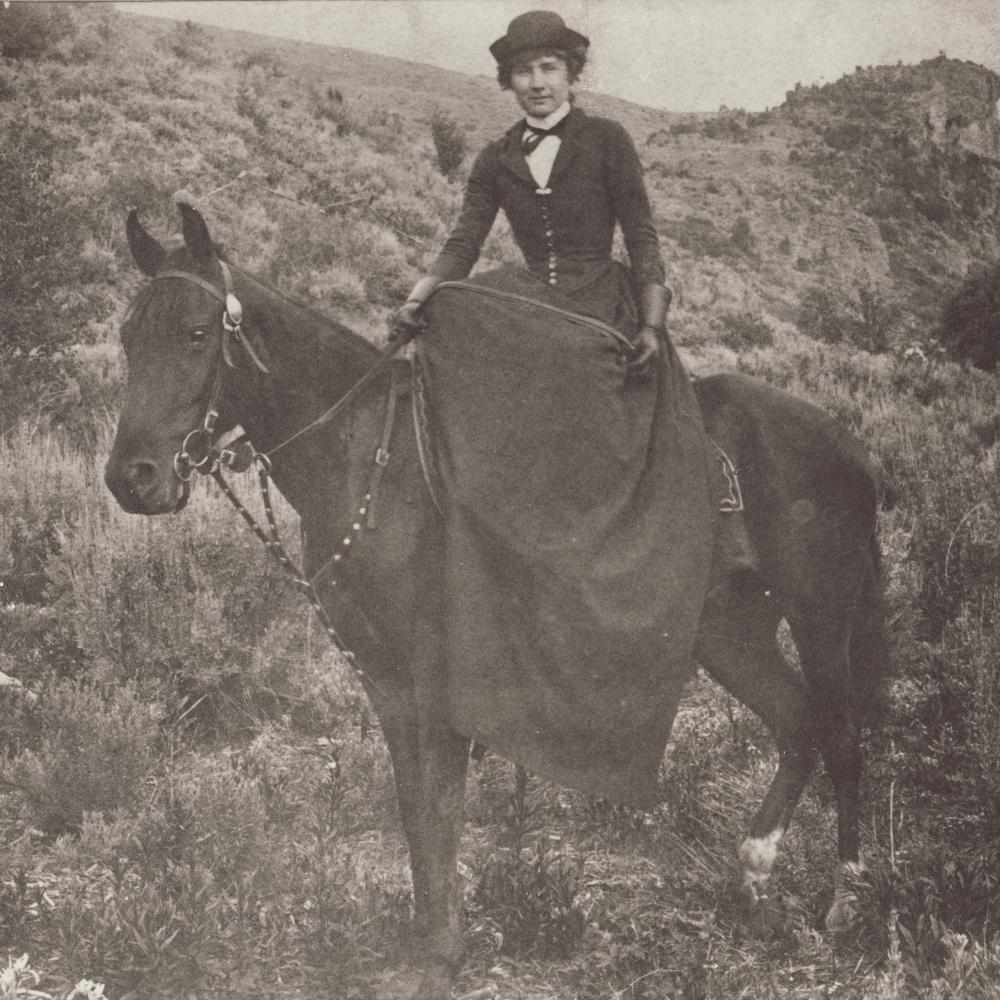

Kittie Wilkins, known as the Horse Queen of Idaho, was perhaps the most famous western woman in the country at the turn of the twentieth century. The Wilkins Horse Company owned close to ten thousand horses in Owyhee County, Idaho, the largest herd owned by one family in the West, and its boss, Kittie, was the only woman at the time whose sole occupation was selling horses. Newspaper reporters all over the country were fascinated by her success and her character, and reports, features, and interviews with her were published in thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia, as well as Canada, Great Britain, and New Zealand.

Today, Wilkins is virtually unknown outside of Owyhee County. Even her gravestone is wrong, naming her “Kitty Wilkins” instead of “Kittie.” Philip Homan, a catalog librarian and associate professor at Idaho State University, is attempting to save Wilkins from obscurity. He is writing the first scholarly biography of her life and gives presentations about her for the Idaho Humanities Council’s speakers bureau program. For Homan, Wilkins’s story is essential to the history of the American West: “To Americans, she was the very model of the westerner, and her story epitomized the West.”

Wilkins was born into the horse-dealing business. Her family began building its enormous herd when she was a little girl in the 1860s. In the 1880s, she began accompanying her father on his business trips to the Midwest, and he soon discovered that she was a natural at horse trading. When she was older, Wilkins was fond of telling the story of how she got her start: When she was two years old, she received a gift of two twenty-dollar gold pieces to be invested for her. Her father took her forty dollars and used it to make a deal on what should have been an eighty-dollar horse. As Wilkins told the San Francisco Examiner, “From the increase, all my bands have come.”

Rather than hiring a commission agent, she sold her horses herself. She traveled to the Midwest and, without a chaperone, attended the livestock markets. “Often I am the only woman in a crowd of two hundred or more horse dealers,” she told the Boston Advertiser. “Sometimes people come out to the stockyards to see in me a new curiosity, and there are a few who try to flirt or make sport of me. I just walk up to a group of such men and, looking them squarely in the face, say, ‘Do you gentlemen wish to look at my horses?’”

Wilkins made the biggest horse sale in the American West in 1900, when she sold about eight thousand horses to a single buyer in Kansas, who was supplying horses to the British Army for the Boer War. Homan points out that Wilkins sold about 10 percent of the American horses that went to South Africa, making her probably the largest supplier of horses in the war.

The later years of Wilkins’s life were marked by tragedy. In 1909, her foreman, who was most likely her fiancé, was shot and killed in a range war over water. Later that year, gold was discovered in Jarbidge Canyon of northeastern Nevada, setting off the last gold rush in the West. In the first few years, the only way to Jarbidge Canyon was over the elevated plateau known as Wilkins Island, the location of Kittie Wilkins’s horse range. Part of the Wilkins’ land included hot springs nearby. “Virtually overnight,” Homan writes in an article for Idaho magazine, “the Jarbidge gold rush turned the Wilkins Hot Springs into a mining camp and the Wilkins Island into the highway to Jarbidge.” Wilkins wanted to build a hotel at the hot springs to take advantage of the new traffic, but in 1910 a squatter on the land claimed possession of it. Wilkins sued the squatter for recovery of the land, but the judge ruled in favor of the defendant and the hotel plans were dashed. “The Wilkins Hot Springs was the strongest link in the Wilkins family’s chain of ranches across Owyhee County,” Homan writes, “and as their hold on the place grew weaker, their wealth and influence began to decline.” Wilkins spent the last years of her life in Glenns Ferry, Idaho, where she spread her remaining wealth among charities.

Homan argues that one of the reasons Wilkins is such an important historical figure is because she differed so dramatically from the stereotype of the “new woman” that prevailed in her time. People expected such a successful female horse dealer to be a “suntanned masculine woman in a short skirt and a cowboy hat.” Instead, they were surprised to find that “she was an utterly Victorian, feminine woman.” She insisted on riding sidesaddle, and always dressed in the latest fashions: “She came to the stockyards and the sale rings in a full riding habit, with a riding skirt down below her toes,” Homan says. “I think this is one of the reasons that perhaps she’s been ignored by contemporary scholars, because she was a Victorian woman. At least at first she opposed women’s right to vote. . . . She wasn’t a feminist in any contemporary sense of the word, except that she was absolutely independent.”