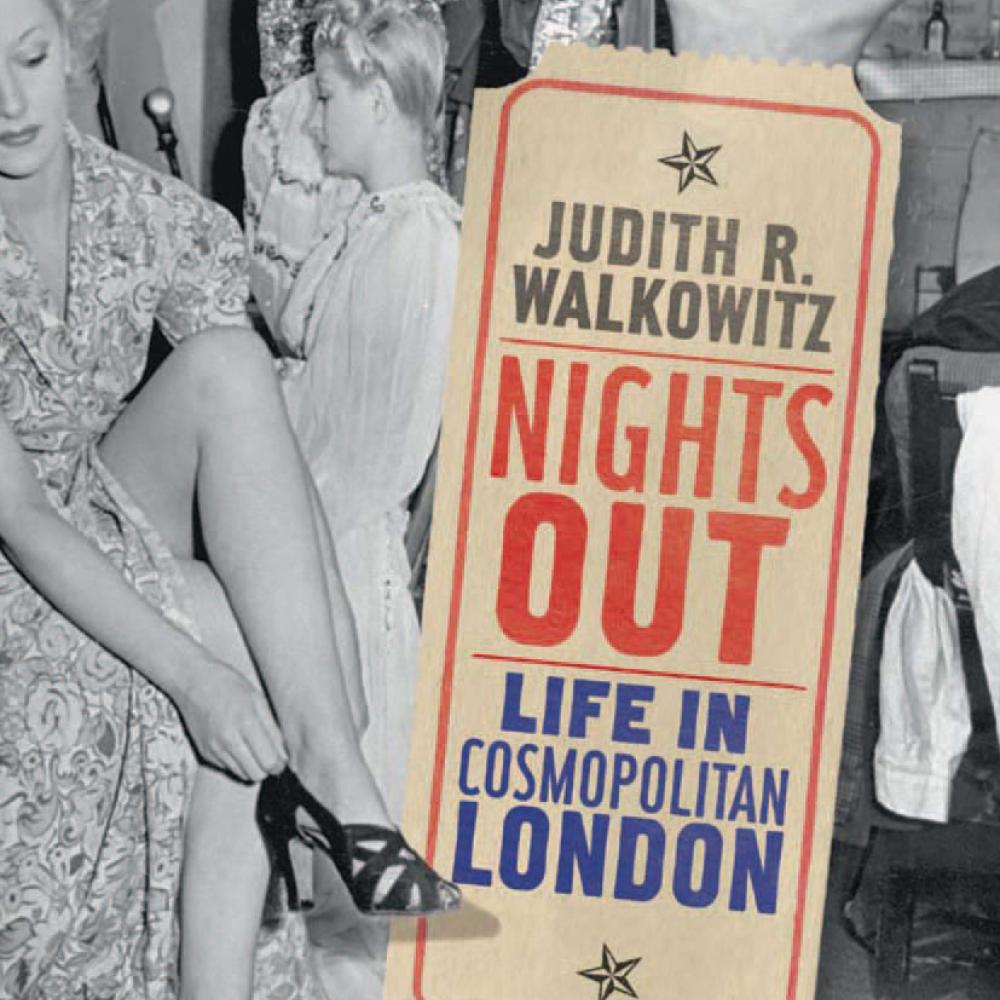

From 1890 to 1945, London’s Soho—bounded by Regent Street on the west, Coventry Street and Leicester Square on the south, Charing Cross Road on the east, and Oxford Street on the north—transformed itself into something more than an industrial hinterland to the West End, and became a hub of cosmopolitanism, where fashion, nightlife, and eateries held sway, uniting the bookish, the stylish, and the raffish in a cauldron of cultures and tastes. An influx of Europe’s diaspora in the latter nineteenth century brought a diversity of language and cuisine to an area no larger than 130 acres and whose population in the twentieth century never exceeded 24,000. In her NEH-funded book, Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London (Yale University Press, 2012), Judith R. Walkowitz ponders the question of how tiny Soho became such a “potent incubator of metropolitan change.”

One answer lies in the retail establishment known as the Corner House, a cavernous, ornate, accommodating food hall providing entertainment and inexpensive fare, in many cases all day and all night. “The Corner Houses,” writes Walkowitz, “were the jewels in the crown of J. Lyons and Company, a food empire that spanned catering, restaurants, hotels, teashops, food processing, food laboratories, and a tea plantation in Africa.” Walkowitz adds that Lyons became “one of the largest employers of free-lance musicians, most of them Jews from the East End or Soho.” Immigrant families, theater workers, musicians, Jewish shopkeepers, and elites such as Virginia Woolf from nearby Bloomsbury, all came to Soho for its mix of eclectic commercialism, vibrant ethnicity, and nonstop entertainment. One Corner House, Coventry Street, “featured seven twelve-piece jazz bands, not to speak of 200 chefs, backed up by a waiting staff of 1,200, who served 400,000 meals a week.”

Among the staff of the Lyons Corner Houses was the Nippy. “The smartly uniformed Nippy, who serviced the many publics of the Corner House and managed their sometimes strained interaction,” Walkowitz writes, “was Lyons’ most successful corporate image. . . . The Nippy was the defining symbol of the feminized world of work that London represented in the 1930s. . . . The Nippy’s up-to-date image was further enhanced by her black and white uniform, from which all ‘emblems of servitude,’ such as high collars and cuffs, and apron strings, had been banished. The Nippy was kitted out as a stylish flapper, in a fitted black alpaca dress, with sixty decorative mother-of-pearl buttons down the front, detachable and starched Peter Pan collar and cuffs, and pinned-on apron.”

One Jewish East Ender remembered, “When you went into the Corner House, you felt like a film star because someone waited on you and the china matched and the tea was in a tea pot, the milk in a jug and sugar in a jar. This was not to mention the cutlery.”