It played out like a John Ford Western—the hero packing a pair of pistols and walking the streets of the dusty town in search of justice and the man who’d threatened his life. But instead of John Wayne in the lead role, the protagonist in this real-life case was a courageous, twenty-two-year-old, African-American firebrand named John Mitchell Jr. As editor and publisher of the African-American weekly newspaper the Richmond Planet, Mitchell was not content to sit in his office—actually, his boardinghouse attic quarters, which doubled as his newsroom at that time—in the face of injustice.

A lynching had taken place at a crossroads in Charlotte County in rural Southside Virginia in May 1886, an event brushed aside in the white press, but taken up in a blistering editorial by Mitchell in the Planet. In response, the journalist received a threatening—and anonymous—letter from Southside with a skull and crossbones on the envelope and the following message: “If you poke that infernal head of yours in this county long enough for us to do it we will hang you higher than he was hung.”

Mitchell printed the letter in his newspaper and added his own response, which he based on a quote from Shakespeare: “There are no terrors, Cassius, in your threats, for I am armed so strong in honesty that they pass me by like the idle winds, which I respect not.” He traveled to the scene of the barbaric crime—walking five miles in plain sight to get there—then strolled around the neighborhood and visited the jail from which the black man had been kidnapped. All the while wearing a pair of Smith & Wesson revolvers. “The cowardly letter writer was nowhere in evidence,” Mitchell later reported.

The young crusader fought against the lynching of both African Americans and whites (though blacks far outnumbered whites as victims of that crime), and he protested against unjust sentences that were being meted out to black prisoners. Mitchell quickly made a name for himself with his daring deeds and became known as the “Fighting Negro Editor” who would gladly “walk into the jaws of death to serve his race.” It was his job, he said, “to howl, yes howl loudly, until the American people hear our cries.”

Mitchell was fearless and had a flair for the dramatic. When he found out that a fifteen-year-old black boy (whom the governor himself would later describe as “very young and weak-minded”) was facing execution in Chesterfield County, Virginia, for allegedly raping a white girl, the editor claimed it would be a “disgrace to the commonwealth” to execute such a young man—regardless of his color. He managed to track down the governor, Fitzhugh Lee (nephew of Robert E. Lee), who was vacationing in the mountains two hundred and fifty miles away, and convince him to issue a stay of execution.

On the eve of the rescheduled hanging, Mitchell once again wrested a reprieve from the governor, then had to make a mad dash in the middle of the night by horse and buggy to deliver the news to the sheriff before dawn. If he got there too late, the boy would be dead. Mitchell arrived just in time. He then interviewed the young prisoner in the jailhouse, describing in the pages of the Planet the pathetic scene he witnessed: the barefooted prisoner, his ankle chained to the stone floor, who was, in Mitchell’s words, “the picture of sadness.” The editor promised the boy, “I’ll go to Richmond and fight for you until the last moment. If I win you will see me again. If I lose you will see me no more.” According to the published account, even the white jailer welled up with tears. A cartoonist as well as writer, Mitchell included sketches in the newspaper that captured the grim details: the gallows that were already in place, the hood the prisoner would have worn, and even the coffin intended for him. Mitchell’s impassioned support riveted the black community throughout the state, and he eventually succeeded in getting the young man’s sentence reduced.

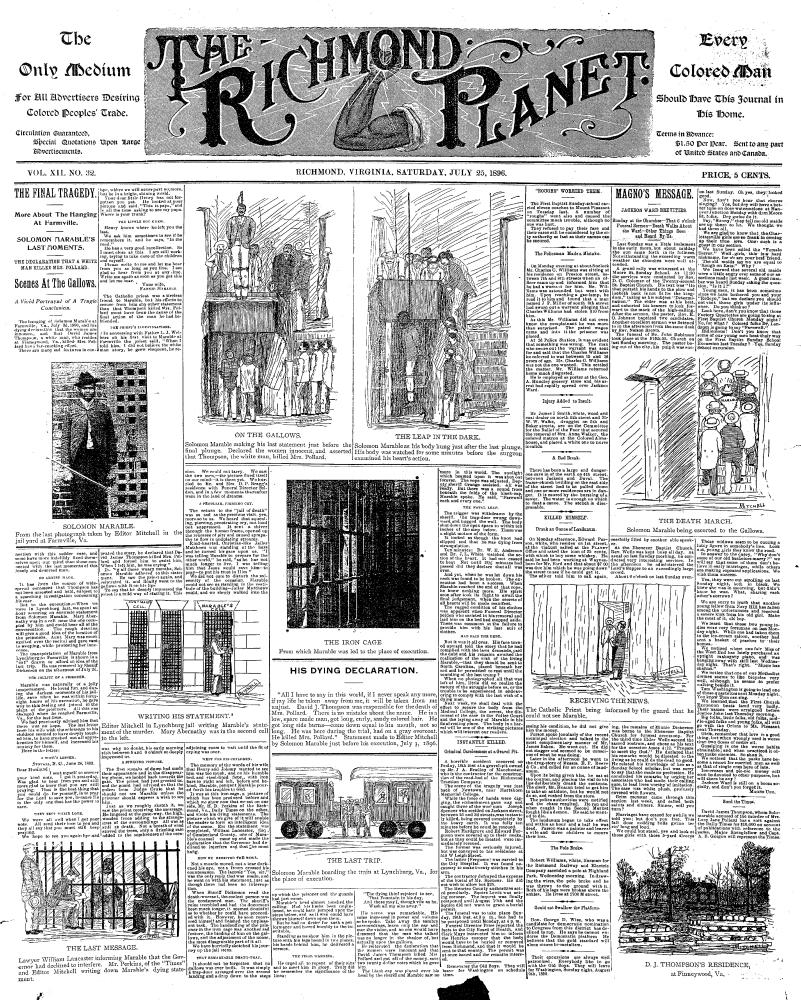

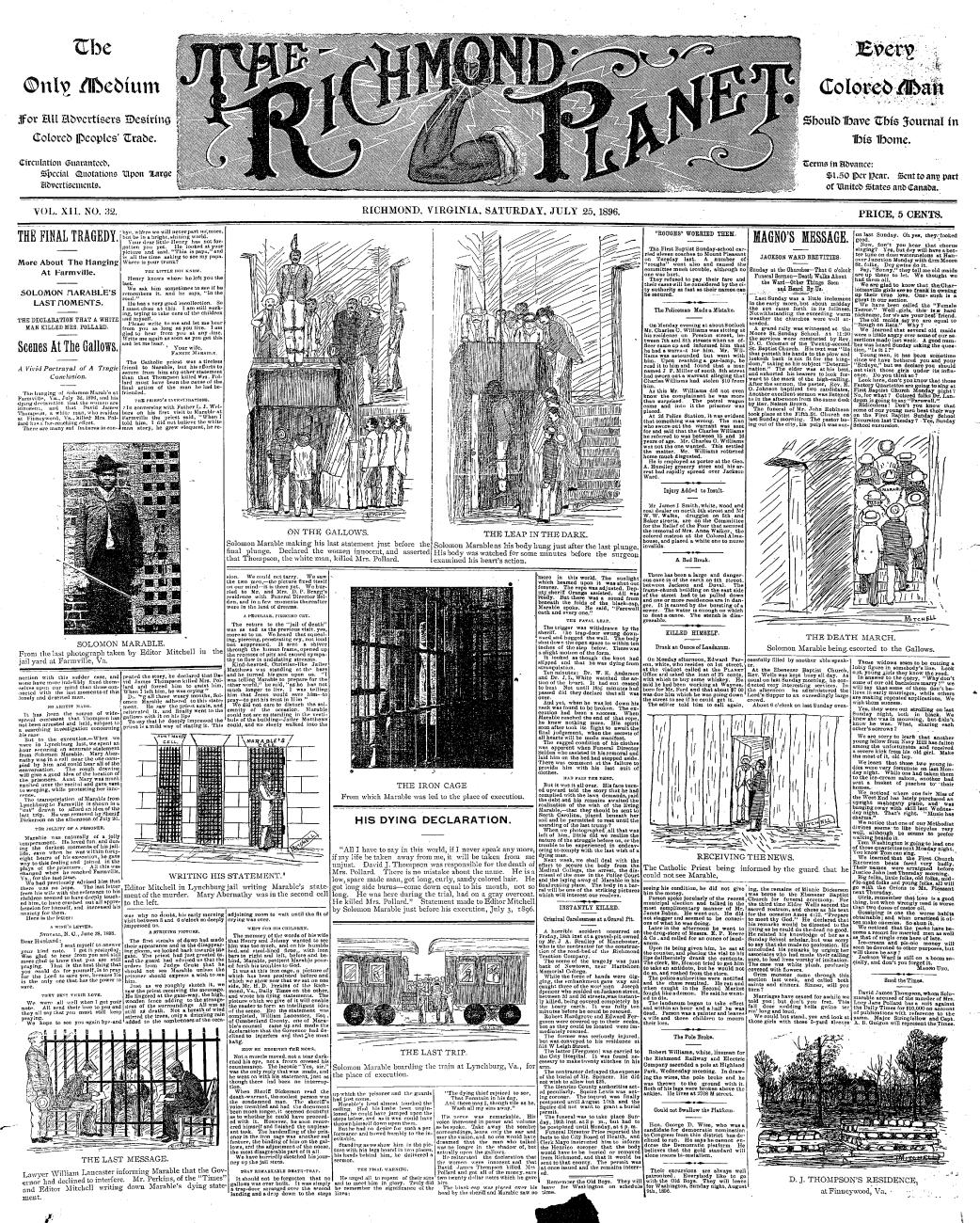

From 1884 until his death in 1929, Mitchell used his newspaper as a vehicle to awaken the conscience of both blacks and whites to the reality of racial injustice. He was a tireless gadfly during an era of lynching and the subsequent disenfranchisement of black voters at the turn of the century. Lynching reached its peak in the South in the early 1890s, when, on average, a black man was hanged every other day for alleged crimes that ranged from rape and murder to hitting a white man or even just writing an insulting letter. The act of lynching had become a grotesque public spectacle with wide swaths of the white community turning out to watch as the victims—many of them innocent of any crime—were tortured, mutilated, and even set afire. Mitchell reported on these atrocities, regularly listing the names of the victims beneath a drawing or photograph of a lynching. Early on he advertised the paper as follows:

Do you want to see what the Colored People are doing? Read the Planet. Do you want to know what Colored People think? Read the Planet. Do you want to know how many Colored People are hung to trees without due process of law? Read the Planet. Do you want to know how Colored People are progressing? Read the Planet. Do you want to know what Colored People are demanding? Read the Planet. . . .

What Mitchell was demanding was basic human decency and justice for African Americans. He espoused middle-class principles of sober hard work and dignified behavior. “Respect white men, but do not grovel,” he wrote. “Hold your heads up. Be men!” But, in the pages of his newspaper, beneath its powerful logo of a flexed, muscular black arm with lightning bolts radiating out of its clenched fist, Mitchell issued some galvanizing opinions of his own. “We regret the necessity,” he wrote, “but if the government will not stop the killing of black men, we must stop it ourselves.” He believed that self-defense was called for when one was under attack: “The best remedy for a lyncher or a cursed mid-night rider is a 16-shot Winchester rifle in the hands of a dead-shot Negro who has nerve enough to pull the trigger.”

Over the years, his paper—one of only a handful of black newspapers produced in the region—carried news of local, national, and international import. Official circulation rose to an impressive 6,400 by 1896, though many more than that actually read its articles, editorials, and advertisements. The paper was passed from person to person, from family to family among the black population of Richmond—much to the chagrin of the editor, who counted on the income generated by the $1.50 yearly subscription rate. (“Do you subscribe to the PLANET or do you borrow it?” he wrote testily on at least one occasion.) But Mitchell also understood that the larger white world needed to be aware of his paper; they needed to read about events from an African-American point of view; they needed to be presented with a portrayal of the black race as hardworking and honorable citizens. Every week he had a copy of the paper delivered to the governor’s mansion in Richmond and to the city’s white newspaper editors.

Who exactly was this John Mitchell Jr., who became one of Richmond’s most influential citizens during an era of bitter racial antagonisms? He was born on July 11, 1863, barely a week after Gettysburg. His parents were slaves in the household of James Lyons, a prominent lawyer who had railed against the Emancipation Proclamation, calling it “inhuman and atrocious” and an act that would “incite servile insurrection against us.” As a member of the Confederate Congress and a pillar of Richmond society, Lyons had entertained Jefferson Davis and the top Confederate military brass in his grand home. At ten years old, Mitchell became his carriage boy, a job for which he needed no education, according to Lyons; Mitchell’s mother, who thought otherwise, taught her son to read and sent him to school. At thirteen, Mitchell was admitted to Richmond Normal and High School, which had been founded by the Freedmen’s Bureau in the postwar era to train teachers. He graduated as valedictorian in 1881 and began teaching in the public schools, a career cut short after three years when a newly elected school board forced out nearly all the black teachers, including him. In 1884, at age twenty-one, he took over the relatively new—but already failing—Richmond Planet and transformed it with his boundless energy, and his talent as both a writer and cartoonist.

While still running the newspaper, Mitchell became a political leader, representing the Jackson Ward black district on Richmond’s city council from 1888 until 1896, when he lost his seat in a crooked election that the Planet, with justification, called the “Jackson Ward Robbery.” After the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1901–1902 succeeded in almost completely disenfranchising black voters, Mitchell adopted different tactics, advocating black economic power as a means to advancement. As head of the fraternal organization, the Virginia Knights of Pythias, Mitchell was already involved in selling insurance; but in 1902 he founded the Mechanics’ Savings Bank for blacks and began investing heavily in Richmond real estate—sometimes in white neighborhoods, to the horror of local residents. Using his newspaper as a bully pulpit, in 1904 he led a citywide black boycott of the newly segregated city streetcars. “Walking is good now. Let us walk!” he wrote, while also offering some hints for aching feet—fish salts and witch hazel were effective remedies, he claimed. In 1910, he built a grand new edifice for his bank—a four-story Renaissance Revival building with a roof garden and marble fixtures in the lobby. The white press reported on the opening under the headline “Colored People Have Skyscraper.”

In 1921, Mitchell even ran for governor on what whites contemptuously called a “lily-black” ticket. He lost in a landslide, and his life began to take a downward turn. Indicted for bank fraud, he was sentenced to three years in prison in 1923. The Supreme Court of Appeals subsequently overturned the conviction, but the damage had been done. His final years were marred by poverty and disgrace—though he remained the ever-feisty editor of the Planet, pleading his innocence. Family lore has it that Mitchell faced death with the same forthright courage that he embodied in life. On December 3, 1929, dressed in his ceremonial Knights of Pythias uniform, he stood up, said “I am ready for you, death,” and promptly died.

Mitchell’s life is an uplifting tale of triumph in the face of racial hatred, an astounding story of passion, talent, and endurance. So, why is he so little known? Beyond a wonderful biography by Ann Field Alexander, entitled Race Man: The Rise and Fall of the “Fighting Editor,” John Mitchell, Jr. published in 2002, which this article draws upon, not much has been written about his dramatic life. In Richmond—a city full of monuments and markers—his legacy was almost completely ignored until recent times. Fortunately, many of his newspapers survive, and they are currently being digitized thanks to the National Digital Newspaper Program, which is funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities and cosponsored by the Library of Congress.

Errol Somay, director of the digitization project taking place at the Library of Virginia, waxes poetic about the Richmond Planet’s heroic editor: “I think John Mitchell Jr. is one of the best kept secrets in Virginia history. Here is a singular figure most people don’t know about—an African American running a newspaper at the height of lynchings.” It has been, in Somay’s words, a “labor of love” on the part of his staff to rescue the crumbling newspapers that looked “like the Dead Sea Scrolls” when they first found them. The pages were so brittle that many broke into confetti-like bits; they had to be pieced together like a puzzle and then put in their proper order.

Somay explained that historic African-American newspapers are “rare as hen’s teeth,” because, compared with the white press, there were far fewer African-American titles, and official repositories generally didn’t bother to collect them. But the Library of Virginia, the official state library, is exceptionally lucky to have one of the most complete holdings of the Planet—the “luck” perhaps due to Mitchell’s weekly habit of sending the paper to the governor’s mansion.

Somay proudly showed me the enormous broadside sheets—with their fascinating array of news stories, cartoons, advertisements, editorials, and heartrending photos of lynchings—that have now been encapsulated in mylar sheets, microfilmed, and digitized. “We’ve done the whole thing soup to nuts. And now people can do their searches from the comfort of their own home”—and discover the life work of an extraordinary crusading journalist.