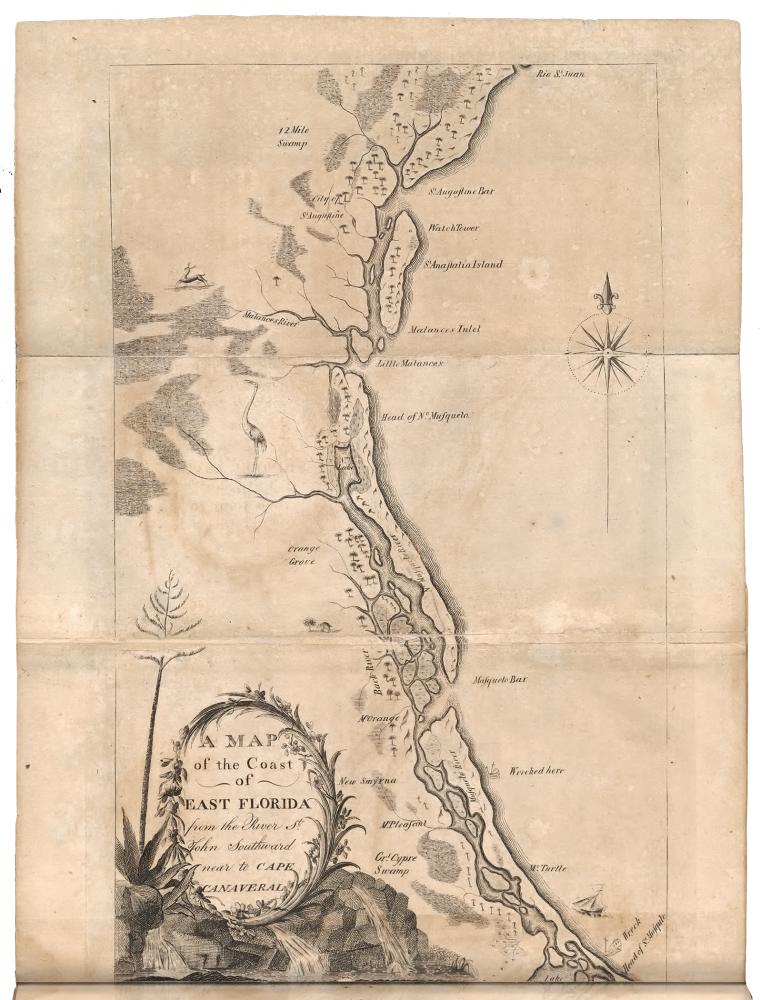

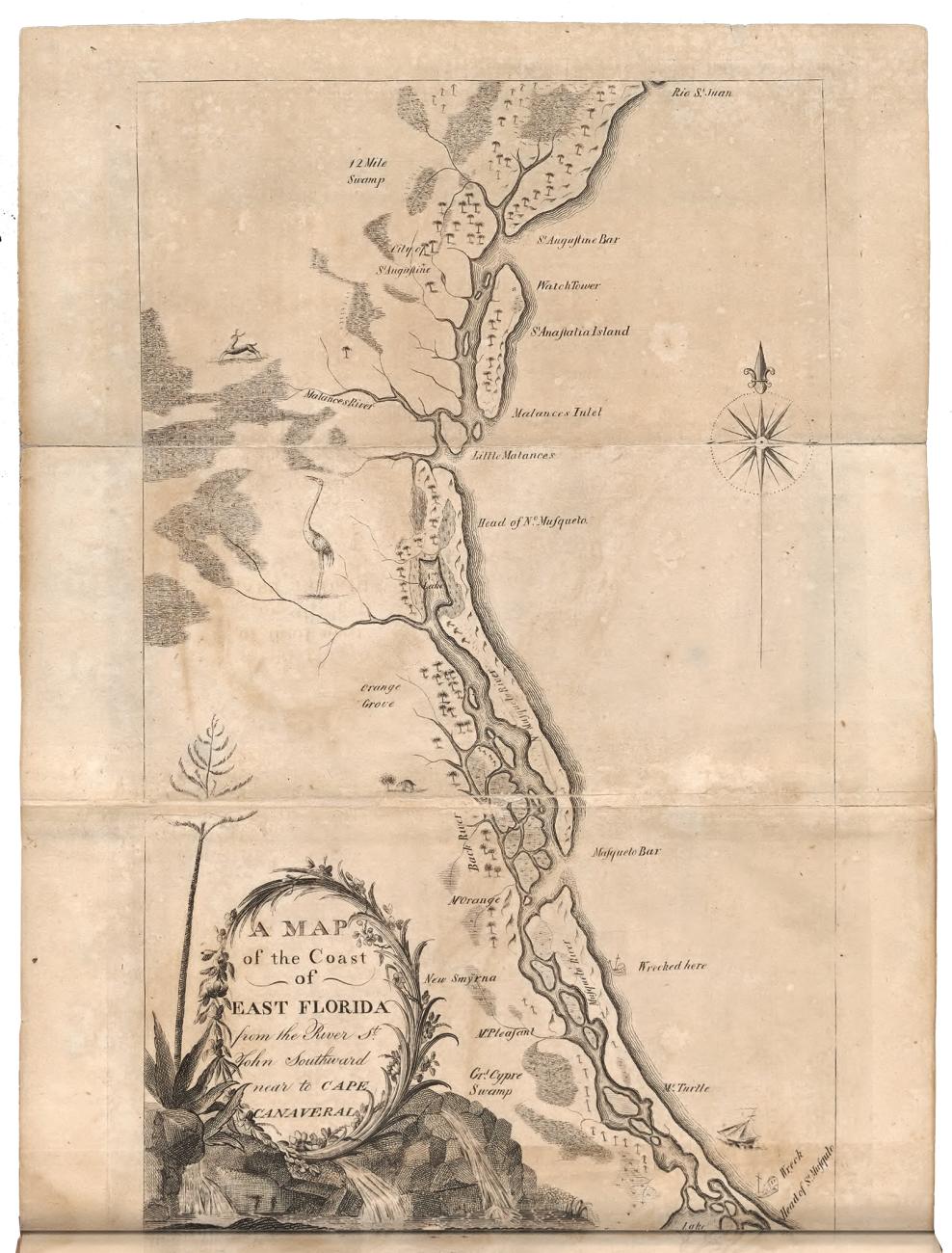

In the spring of 1774, Philadelphia naturalist William Bartram journeyed up the St. Johns River in East Florida and encountered a series of terrifying alligators.

Bartram was in the second year of a nearly four-year expedition through the frontier wilds of southeastern North America, a trip sponsored by the British physician, plant collector, and fellow Quaker John Fothergill. Almost two decades later, Bartram memorialized his experience in Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida (1791), which remains the most famous account of this curious reptile, the American alligator.

Bartram’s story begins on a “temperately cool and calm” evening, when he found a spot to set up camp on a twelve-foot-high bluff overlooking a point in the river that widened into a small freshwater lake, now known as Lake Dexter. Soon after arriving, Bartram noticed that “crocodiles began to roar and appear in uncommon numbers along the shores and in the river.” Looking down from the bluff, he spotted a cove about 100 yards away that opened into a lagoon, a shallow area where he witnessed an alarming struggle between two large alligators.

Using vivid, captivating language, Bartram stressed the size, power, and ferocity of the creature: “Behold him rushing forth from the flags and reeds. His enormous body swells. His plaited tail brandished high, floats upon the lake. The waters like a cataract descend from his opening jaws. Clouds of smoke issue from his dilated nostrils. The earth trembles with his thunder.” When his “rival champion” arrived from the opposite shore, the two alligators “suddenly dart[ed] upon each other” in a “horrid combat” that roiled the waters and echoed through the surrounding forests. Bartram dubbed the site “Battle Lagoon” to commemorate the epic conflict.

Although daunted by the prospect of venturing back onto the water, especially with darkness about to fall, Bartram was also hungry. So, after a long day of travel, he reluctantly headed out in his canoe to secure fish for dinner. Several large alligators immediately began stalking him as he hastily paddled toward the entrance of the lagoon. Armed with only a club and barely halfway to his destination, he found himself engaged in what he depicted as a life-or-death struggle:

I was attacked on all sides, several endeavoring to overset the canoe. My situation now became precarious to the last degree: two very large ones attacked me closely, at the same instant, rushing up with their heads and part of their bodies above the water, roaring terribly and belching floods of water over me. They struck their jaws together so close to my ears, as almost to stun me, and I expected every moment to be dragged out of the boat and instantly devoured.

Bartram managed to fend off the attack, catch several trout, and safely return to camp. As soon as he stepped onshore, however, a menacing 12-foot long alligator “rushed up near my feet.” Bartram dashed back to his campsite to retrieve his gun and dispatched the bold reptile with a single shot to the head. He then began cleaning the fish he had caught but was quickly interrupted when another “very large alligator” lunged forward. This one swept away several of Bartram’s fish with its tail just as the naturalist stepped aside. Had he not moved, Bartram reported, “the monster would probably . . . have seized and dragged me into the river.”

As dusk arrived, Bartram was struck by another “tumultuous noise,” and peering down from the bluff he observed a “prodigious assemblage of crocodiles . . . , which exceeded everything of the kind I had ever heard of.” The alligators were so closely crowded together that he claimed he could have walked from “shore to shore” across their heads, “had the animals been harmless.” He witnessed “the devouring alligators” swallow “thousands, I may say hundreds of thousands” of fish as they struggled to crowd through a narrow pass. “The horrid noise of their closing jaws, their plunging amidst the broken banks of fish, and rising with their prey some feet upright above the water, then floods of water and blood rushing out of their mouths and the clouds of vapour issuing from their wide nostrils, were truly frightful.” The “shocking and tremendous” feeding frenzy kept him awake most of the night.

The next morning the sleep-deprived Bartram seriously considered abandoning plans to continue his upriver travels but then decided to give it one more day. Just as he was crossing Battle Lagoon, though, a “huge alligator rushed out of the reeds, and with a tremendous roar, came up, and darted as swift as an arrow under my boat, emerging upright on my lea quarter, with open jaws, and belching water and smoke that fell upon me like rain in a hurricane.” While Bartram once again managed to beat back the attacking alligator with his club, he endured several other frightening encounters with the species before the day ended.

Bartram’s alligator stories are certainly compelling, but are they true? Did he actually experience everything he wrote about the reptile in Travels? Scholars who have scrutinized his correspondence, journals, and publications have long noted that Bartram could be careless with dates and often exaggerated the sizes, quantities, and distances of the objects and places he described, whether knowingly or unknowingly. Bartram aimed for general accuracy in a work he hoped would simultaneously represent a contribution to science, presenting “new as well as useful information to the botanist and zoologist.” He also wanted to celebrate God’s handiwork in what one biographer has described as an “ode to unspoiled natural beauty.”

But we know that he presented some episodes in Travels out of their actual chronological order to strengthen the narrative and heighten its dramatic effect. We also know from the report that he sent to his patron John Fothergill in 1774 that he was actually traveling with a companion, not alone as he portrayed in Travels, when he encountered a fearsome congregation of alligators on Florida’s St. Johns River.

His experience of the alligator—and the lurid description of that experience that he published—might have been unconsciously biased by previous accounts of crocodilians, which almost invariably stressed their ferocity. His desire to refute the famed French naturalist Buffon, whose theory of degeneracy had depicted the fauna (and people) of the New World as weak and feeble, might also have colored his presentation of the species as large, aggressive, and frightful. In short, while naturalists have verified much of what Bartram wrote about the alligator, some of his claims continue to elicit skepticism and debate. The ferocity of the alligator is one of those contentious claims.

Part natural history, part travelog, Bartram’s engaging book is one of the great classics of American nature writing. Its florid descriptions inspired the British Romantic poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge and the American Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, among many others. Travels, which remains in print to this day, is also a pioneering contribution to the natural history of the southeastern United States. Bartram’s account of the flora and fauna he encountered during his four-year journey includes over 130 plants that were new to science.

While many would question the veracity of Bartram’s version of his brush with the American alligator, his description has long remained a touchstone for subsequent naturalists who wrote about the species. Indeed, Bartram’s memorable depiction of the reptile as a ferocious, man-eating monster helped make the alligator into the fearsome icon that it has become and continues to shape responses to the species today. Despite the tireless efforts of wildlife biologists, game officials, and other experts who have long insisted that the risk of alligator attack is exceedingly remote, most Americans continue to disproportionately fear the species.

When it was finally published in 1791, the initial reception to Bartram’s Travels was mixed. One reviewer thought the book “entitle[d] the author to a respectable place among those, who have devoted their time and talents to the improvement of natural science” but also lamented the many “rhapsodical effusions” that “might have been omitted . . . with advantage to the work.” Another reviewer echoed this sentiment, acknowledging that Bartram had “accurately described a variety of birds, fish and reptiles, hitherto but little known,” while criticizing his language as “rather too luxuriant and florid, to merit the palm of chastity and correctness.”

Whether offering critique or praise, most reviewers seemed enthralled by Bartram’s dramatic confrontation with alligators on the St. Johns River. A review in the British periodical The Monthly Review; or, Literary Journal included a lengthy extract from Bartram’s alligator encounter that was so terrifying that the reviewer said it made the reader “shudder,” and then noted that after “perusing his descriptions, it is most certain that we will never chuse to visit” the homeland of that “horrible monster.”

After Bartram, the next lengthy account of the alligator came from the hand of the American artist and naturalist John James Audubon. In 1826, Audubon traveled from New Orleans to England to find an engraver to print and subscribers to underwrite his Birds of America, a monumental publication that would include 435 hand-colored, life-size engravings of all the known birds of North America, a total of nearly five hundred species. In an effort to drum up support for the ambitious project, Audubon exhibited his magnificent watercolor bird portraits and published several articles, including “Observations on the Natural History of the Alligator,” that he hoped would shore up his bona fides.

Based on personal observations made while living and traveling in Louisiana and Mississippi, Audubon’s account failed to mention Bartram by name, but the opening paragraph challenged the notion that the alligator was an aggressive, bloodthirsty reptile. After proclaiming the alligator to be “one of the most remarkable objects connected with the natural history of the United States,” Audubon argued it is “neither wild nor shy, neither is it the very dangerous animal represented by travelers.”

Audubon then seemed to echo Bartram—and backtrack a bit—when he noted that the alligator’s large, powerful tail was its chief means of defense or attack: “Woe be to him who goes within reach of this tremendous thrashing instrument, for no matter how strong or muscular; if human, he must suffer greatly, if he escapes with his life.” Audubon admitted that he was terrified when he first encountered large numbers of alligators while traveling through Louisiana’s wetlands, but, with a local hunter yielding a small club leading the way, he soon felt quite at ease, even in waist-deep water that was crawling with the reptile.

“They will swim swiftly after a dog, or a deer, or a horse, before attempting the destruction of a man,” Audubon asserted, “if the man feared not them.” He did admit that during the spring, when waters were low, food was scarce, and mates were being sought, the species could be “dreadfully dangerous,” “ferocious,” and “very considerably more active”: “At this time no man swims or wades among them; they are usually left alone at this season.” For Audubon, then, context mattered and, during certain times of the year, the alligator could be quite deadly.

The American Revolution and the ensuing War of 1812 unleashed an ardent nationalism in the United States, including a desire to gain scientific independence to accompany the young nation’s hard-won political freedom. Rather than continuing to rely on European experts to name and describe their native species, American naturalists increasingly sought to craft their own authoritative natural history inventories. The most economically important species—birds, mammals, fish, and insects—received the lion’s share of attention, but by the mid 1820s the South Carolina physician and naturalist John Edwards Holbrook began gathering material for a book describing all the known reptiles and amphibians in the United States. In the preface to the first edition of his beautifully illustrated North American Herpetology, first published in four volumes between 1836 and 1840, Holbrook declared, “In no department of American zoology is there so much confusion as in herpetology.” The first comprehensive study of its kind, Holbrook’s book gained international recognition as it sought to impose order on that chaos.

Its entry for the American alligator listed all the scientific names that had been conferred on the species over the years, gave a technical description of the reptile, and discussed its geographical distribution and habits. Holbrook pointed out that in the mid eighteenth century the British naturalist Mark Catesby provided the first proper description and “tolerable figure” of the species. In 1801, the famed French comparative anatomist and paleontologist Georges Cuvier became the first to accurately sort out the differences between the crocodilians of the Old and New Worlds. He suspected that the American alligator was a distinct species from the South American animal but awaited further evidence to make a definitive ruling. A year later, one of Cuvier’s colleagues, the French zoologist François M. Daudin, published an account of the animal under the name Crocodilius mississipiensis (inadvertently misspelled) based on a specimen taken from the Mississippi River. In 1807, Cuvier described the American alligator as a new species under the scientific name Alligator lucius. Daudin’s specific name had priority, Holbrook declared, so the appropriate binomial should be Alligator mississippiensis. Competing scientific names for the species continued to circulate, but Holbrook’s ruling—complete with a correct spelling—eventually won the day.

Holbrook’s account of the alligator repeatedly referenced Bartram. He noted that the species could grow to a length of 13 1/2 feet in the Carolinas, while Bartram claimed it could reach more than 23 feet in Florida, “a size almost incredible.” During the spring and early summer, alligators often made a startling noise—a “croak . . . not unlike that of the bull-frog, but louder and less prolonged; Bartram compares it to distant thunder!” Holbrook waffled on whether alligators routinely attacked humans. He claimed that the species is “more timid than is commonly supposed,” but then immediately added, “at least on land.” He knew of no authenticated instance of the reptile “having preyed on man” in the Carolinas, but he left open the possibility that it might act more aggressively toward humans in the southern portion of its range. After recounting Bartram’s description of the alligator being so “very ferocious” that he was “nearly devoured by one” while in Florida, Holbrook warned that the Philadelphia naturalist’s words should be “received with some caution.” He then suggested that the reptile’s behavior might be malleable, depending on whether it had experienced much contact with humans: “perhaps . . . the encroachments of man upon their dwelling-places, since Bartram wrote, may have rendered them more timid and distrustful.”

The Scottish naturalist Charles Lyell, who helped lay the foundations for modern geology by arguing that known natural causes could explain the history of the Earth, gave even more credence to Bartram’s account of the alligator. In the 1840s and 1850s, Lyell made four trips to the United States, totaling more than two years, where he traveled widely to lecture and pursue field work. In a published account, Lyell noted that he was near Butler Island, Georgia, when he spotted a nine-foot alligator basking in the sun. The species had once been much more abundant and fearless, he noted, but now it had grown shy “since they have learnt to dread the avenging rifle of the planter, whose stray hogs and sporting dogs they often devour.” Lyell then commented favorably on Bartram’s reliability: “When I first read Bartram’s account of alligators more than twenty feet long, and how they attacked his boat and bellowed like bulls, and made a sound like distant thunder, I suspected him of exaggeration, but all my inquiries here [in Georgia] and Louisiana, convinced me that he may be depended on.”

The American naturalist John Eatton Le Conte also vouched for Bartram’s reliability. Le Conte spent winters on a family-owned rice and cotton plantation in southeastern Georgia and published widely on plants, insects, crustaceans, amphibians, and reptiles, particularly turtles. In 1822, a year after Florida became an official U.S. territory, he secured federal funding to explore the St. Johns River, with the aim of discovering its source. Over three decades later he published an article highlighting a series of North American animals that had not been seen since they were originally described, including several species that Bartram had included in his Travels.

“I remember when it was much the custom to ridicule Mr. Bartram and, to doubt the truth of many of his relations,” he wrote.

For my own part, I must say, that having travelled in his track I have tested his accuracy, and can bear testimony to the absolute correctness of all his statements. I travelled through Florida before it was overrun by the present inhabitants, and found everything as he reported it when he was there, even to the locality of small and insignificant plants. Mr. Bartram was a man of unimpeached integrity and veracity.

By the twentieth century, naturalists who spent a great deal of time observing the alligator in the field were much more likely to challenge Bartram’s characterization of its aggressive behavior toward humans. Albert M. Reese, who earned his doctoral degree in biology from Johns Hopkins University, authored the first scientific monograph on the reptile, The Alligator and Its Allies, in 1915. After research trips to Florida and southern Georgia, Reese argued that the alligator was not a particularly aggressive species. While it would defend itself when cornered, like most other wild animals, Reese commented, “it will always flee from man if possible, and the writer has frequently waded and swam in ponds and lakes where alligators lived without the least fear of attack.” Echoing Holbrook, Reese did admit that this might not have been possible in the days when alligators were “more numerous and had not been intimidated by man and his weapons.”

Two decades later, the wealthy Louisiana entrepreneur, sportsman, conservationist, and amateur naturalist Edward A. McIlhenny published The Alligator’s Life History (1935), based largely on firsthand observations made over more than five decades in the area surrounding his family’s large estate on Avery Island. The site was not only prime alligator habitat but also home to the McIlhenny Company, which his father had established to produce Tabasco brand pepper sauce. McIlhenny and his boyhood playmates felt so little fear of the species that when they went swimming in streams they “paid no more attention to them than we did the flocks of birds about the place” and even made a game of pelting large alligators with mud. He acknowledged that the reptile might kill dogs and livestock, even a full-grown cow, but he vehemently denied that it would go out of its way to attack humans. The two exceptions were alligators provoked by hunters or trappers trying to capture them and females defending their nests.

Others who intensely studied or lived in proximity to the alligator generally agreed that it was rarely aggressive toward humans. A similar conclusion could be reasonably drawn from records kept by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, which has been tracking alligator attacks since the 1970s. Over the past 50 years, the number of alligator attacks in Florida has been averaging between 3.5 and 7 per year, and the number of fatal encounters has averaged less than 1 every two years. This remarkably low rate has occurred in a state that now has an estimated 1.3 million alligators, 21.5 million residents, and over 129 million visitors each year. Yet the perception of the species that has predominated in the broader culture is one of great fear.

One curious absence in the history of interactions with the American alligator is a systematic effort to eradicate the species. Since the publication of Barry Lopez’s Of Wolves and Men in 1978, numerous scholars have documented the fear and loathing that Americans have long directed toward top-level carnivores, especially the wolf, coyote, bear, and cougar. Informed by enduring myths and fearful for their livestock and personal safety, European settlers in North America waged a brutal campaign of extermination that began soon after their arrival and spread across the continent as whites moved westward and southward.

As environmental historian Jon T. Coleman notes in his sobering account of the campaign to eradicate the gray wolf, American colonists “shared a conviction that wolves not only deserved death but deserved to be punished for living.” Driven by that deep-seated hatred, they engaged in unspeakable acts of cruelty directed against the species they persecuted, like burning wolves alive, dragging them behind their horses, turning them to their dogs after hamstringing them, wiring their mouths shut, feeding them sharp hooks buried in balls of tallow, and poisoning them with abandon. Over time the relentless crusade to eradicate North American predators dramatically reduced numerous species, pushing several, including the wolf, to the very brink of extinction. Although the alligator has also triggered general fear and anxiety, it has been spared from the aggressive bounty programs designed to wipe out other large predators.

Why has the alligator proven the exception? It turns out that while we tend to hold a deep visceral fear of the reptile as a potential assailant, our attitudes toward this apex predator are complex and multifaceted. While the alligator terrifies us, just as it clearly did Bartram, it has also been valued as a landscape symbol, a precious commodity, an endangered species, and a sentinel species alerting us to the dangers of the toxic substances we have introduced into the environment. Because of these many positive associations, we have rescued the alligator from the threat of extinction it faced due to overhunting in the mid twentieth century, and we have now found a way to coexist with large populations of the species.

Bartram was not the first to propagate the myth of the alligator as bloodthirsty, man-eating predator, nor would he be the last. His vivid, sensational, and widely reproduced depiction of the American alligator was consistent with previous accounts of crocodilians that had been circulating in the West for two millennia, and it has continued to shape broader cultural perceptions of this curious reptile for more than two centuries.