Last year, Sotheby’s auction house in London sold a vintage, double-elephant folio copy of John James Audubon’s Birds of America for $11.5 million, setting a record for the most expensive printed book in history. The sale affirmed Audubon’s stature as the world’s most celebrated bird artist, but by at least one standard, the original Birds of America remains an incomplete masterpiece.

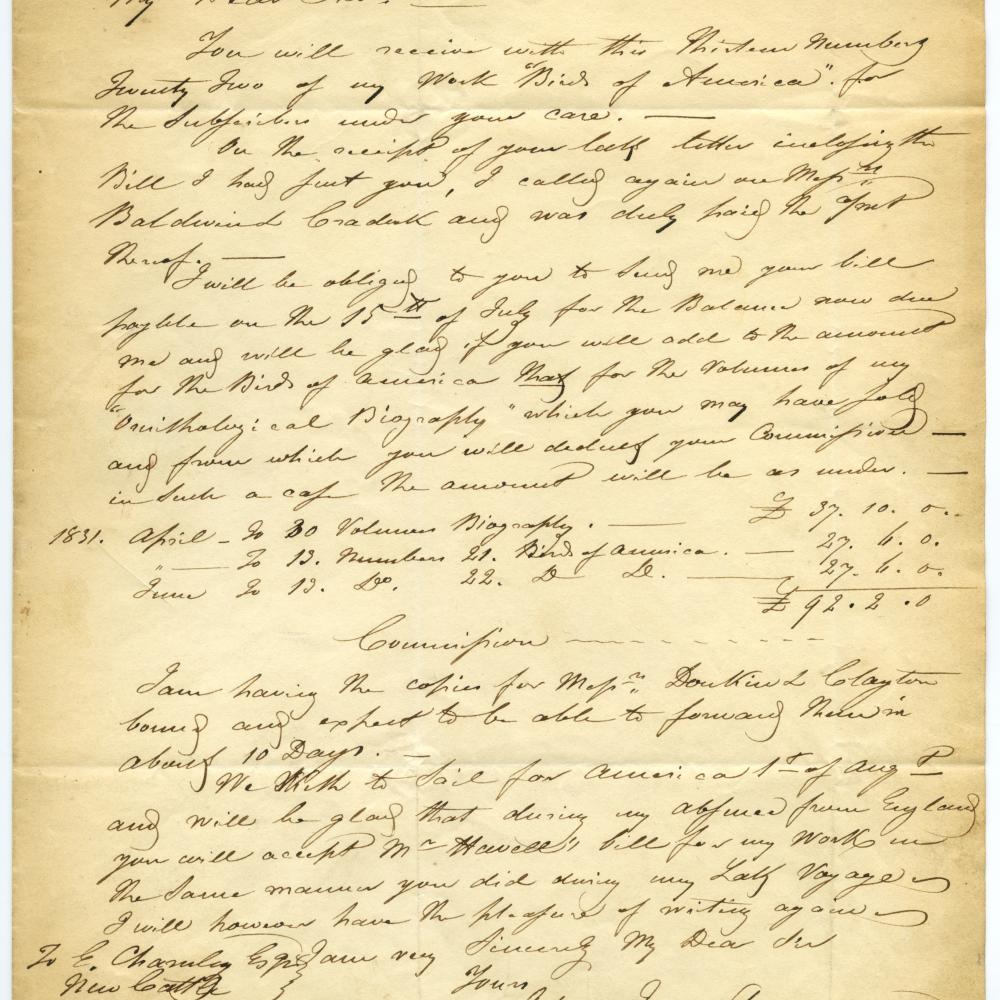

First published in England, where he had gone to find the best printer available, Audubon’s massive collection of 435 bird illustrations confronted a curious legal provision when it first appeared between 1827 and 1838. British copyright law stipulated that copies of all books containing text be deposited in crown libraries around the country, and the expense of that requirement would have fallen on Audubon. The prospect of producing so many library copies of his book was overwhelming, since the high production values of Birds of America gave each edition a whopping price tag of about $1,000 or roughly $23,000 in today’s money.

Faced with economic reality, Audubon devised a resourceful loophole. To avoid the British copyright requirement, he published Birds of America essentially without text, leaving his written bird profiles and ornithological anecdotes for other publishing projects. Over time, Audubon’s vivid prose reflections would surface in other books, such as his lively, multivolume Ornithological Biography, published between 1831 and 1839. But that first separation between Audubon’s pictures and his words has shaped his legacy for generations. His art gained enduring international fame, while his substantial body of nature writing, detoured into other venues, endures in relative obscurity.

In recent years, though, a small but dedicated community of Audubon admirers has been trying to give Audubon the writer his due. Scott Russell Sanders, one of America’s most accomplished living nature writers, counts Audubon’s prose as a critical source of inspiration. “We are all familiar with Audubon the painter,” Sanders writes. “Reproductions of his vivid birds and beasts hang in our courthouses, lie in slick books on our coffee tables, decorate our bedrooms and greeting cards. Say his name, and in the minds of most listeners a colored print will arise. But Audubon was also a writer, and a remarkable one.”

Sanders made an early and important contribution to raising Audubon’s profile as a writer by editing Audubon Reader, a 1986 anthology of his best prose. Sanders is also the author of a 1984 novella on Audubon’s early years, Wonders Hidden. John James Audubon: Writings and Drawings, a Library of America anthology edited by Audubon scholar Christoph Irmscher, followed in 1999.

Irmscher is also the brainchild behind “Picturing John James Audubon,” an NEH-funded summer institute in which teachers from across the country gather to study Audubon’s writing as well as his art, gaining insights to bring back to their classrooms. Based at Indiana University in Bloomington, the institute held its first session in 2009, and subsequent funding enabled another summer session earlier this year.

The monthlong institute included sessions in which Irmscher, a professor of English at IU, led students in discussions of Audubon’s journals. Sanders, now retired from IU’s English faculty and another lecturer at the institute, headed a session provocatively titled “The Raw and the Cooked: Audubon as a Nature Writer.”

Slowly, the word about Audubon’s literary gifts seems to be reaching a wider audience, thanks in part to recent biographies that chronicle both Audubon’s skill with a paintbrush and his genius with a pen. While researching his 2004 biography, John James Audubon: The Making of an American, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Richard Rhodes became so enamored with Audubon’s prose that he followed the biography with his own Audubon Reader in 2006.

Rhodes’s anthology, like the Sanders and Irmscher collections, reveals a literary artist who wrote letters, journals, and essays as a daring form of autobiography, so that regardless of his ostensible topic, Audubon was usually, on some level, writing about himself. Drawing on the narrative of one’s life is only compelling, of course, if the life behind the page is consistently interesting, and on that score, Audubon benefited from unusually good source material. He led a life that begged to be captured in print.

John James Audubon was born on April 26, 1785, in Saint-Domingue, in what is now Haiti. He was the product of a union between a French father, Jean Audubon, who had a sugar plantation on the island, and a French chambermaid who died shortly after his birth. The Haitian Revolution forced Audubon and his father to return to France, where they arrived just in time for the terrors of the French Revolution. Audubon, his father, and his adoptive mother narrowly escaped the slaughter.

In 1803, Audubon’s father sent him to America to avoid the young man’s conscription into Napoleon’s army, assigning Audubon to manage Mill Grove, the family’s plantation near Norristown, Pennsylvania. Audubon’s new neighbors included the young and beautiful Lucy Bakewell, who became Audubon’s wife in 1808. Two years later, the Audubons settled in the new frontier town of Henderson, Kentucky, where he prospered as a merchant and mill owner. But an economic downturn, the Panic of 1819, threw many businesses into bankruptcy, and the Audubons, who were among the casualties, saw their fortunes vanish.

With nothing to lose, Audubon decided to pursue a career as a full-time painter, an avocation he had enjoyed since childhood. So began his nomadic trek through several states, getting occasional commissions to support his family, which now included two young sons, as he gathered material for Birds of America. Lucy, whose steadfast support and shrewd counsel would establish her as the Abigail Adams of American ornithology, helped sustain the household by working as a teacher.

By 1826, after years of perilous struggle, Audubon had gathered enough material to sail to England, where he hoped to get critical financing and technical support to bring Birds of America to press. Exhibits of his work in Liverpool, Manchester, and Edinburgh created a sensation, and the subsequent publication of Birds of America helped secure his fame and fortune. Audubon remained active as an artist and naturalist until shortly before his death at Minnie’s Land, his New York estate, on January 27, 1851.

“If Audubon’s life sounds like a nineteenth-century novel with its missed connections, Byronic ambitions, dramatic reversals and passionate highs and lows,” Rhodes writes, “nineteenth-century novels were evidently more realistic than moderns have understood.”

In equating Audubon’s life—and, by extension, his writing—with period fiction, Rhodes subtly points us toward a key principle of Audubon’s literary legacy. To the degree that Audubon’s prose has the shapely feel of a novel, it’s because he was deft at crafting his observations into the stuff of story; the birds that he chronicles became not merely objects of scientific data, but characters in a dramatic narrative.

Instructively, as he traveled into the woods of Louisiana to do some of his best pictures and his most memorable writing, Audubon carried a copy of a favorite book, the fables of Jean de La Fontaine, along with him. La Fontaine (1621–1695) had gained fame by borrowing freely from Aesop, penning witty allegories in which animals are cast in human situations.

Like La Fontaine, Audubon was a quaint moralist about the natural world, assigning human strengths and weaknesses to the creatures he chronicled in his writings. The result is dubious science, but lively reading. Audubon gets into high dudgeon, for example, about the blue jay, a bird he accuses of vanity and theft: “Who could imagine that a form so graceful, arrayed by nature in a form so resplendent, should harbor so much mischief;—that selfishness, duplicity, and malice should form the moral accompaniments of so much physical perfection! Yet so it is, and how like beings of a much higher order, are these gay deceivers!”

Audubon’s anthropomorphic view of the birds he encountered might sound archaic by the yardstick of modern ornithology, but on at least one level, the morality plays of his expansive aviary seem thoroughly modern. Read Audubon for any length of time, and you realize that his careful distillation of nature into narratives of good versus evil anticipated the age of television wildlife documentary. When we watch TV shows that are carefully constructed to make us root for the terrified antelope as it runs from the hungry lion, we’re indulging a tradition that Audubon, America’s abiding dramatist of the great outdoors, helped to popularize.

Audubon’s writings, like his pictures, also foreshadow the crackling intensity of the small screen in their view of nature not as passing scenery, but as a scene of action. Audubon’s prose and his art present a rugged landscape in which something is always happening. Listen to how much his opening passage in an essay on the Mississippi kite sounds like the stage directions in a film script:

When, after many a severe conflict, the southern breezes, in alliance with the sun, have, as if through a generous effort, driven back for a season to their desolate abode the chill blasts of the north; when warmth and plenty are insured for a while to our happy lands; when clouds of anxious Swallows, returning from the far south, are guiding millions of Warblers to their summer residence; when numberless insects, cramped in their hanging shells, are impatiently waiting for the full expansion of their wings; when the vernal flowers, so welcome to all, swell out of their bursting leaflets, and the rich-leaved Magnolia opens its pure blossoms to the Humming Bird;—then you will see the Mississippi Kite, as he comes sailing over the scene. He glances toward the earth with his fiery eye; sweeps along, now with the gentle breeze, now against it; seizes here and there the high-flying giddy bug, and allays his hunger without fatigue to wing or talon.

That excerpt from Audubon’s Ornithological Biography teaches us a few things about the environs of the Mississippi kite and a little bit about the actual bird, but it also throws light on Audubon himself. Not every writer would attempt an opening sentence that stretches to 126 words, and Audubon’s audacity in doing so hints at the supreme self-confidence he could muster in his professional pursuits.

The sheer scale of Birds of America, which required pages that were more than two feet wide and more than a yard high because of Audubon’s insistence on rendering life-size depictions of his subjects, is perhaps the most compelling evidence of his artistic swagger. Who else but Audubon would produce a prototypical coffee-table book that’s literally the size of a coffee table? Rhodes estimates that Audubon, who started his art career in earnest as a penniless painter, had to raise the modern-day equivalent of $2 million to produce Birds of America, a challenge that would have daunted men with less grandiose views of their personal abilities.

Audubon’s ebullience also shoots up like a signal flare in his fetish for capitalization, which compels him to write of swallows as Swallows, warblers as Warblers, and the hummingbird as a Humming Bird. At first glance, this seems like a stylistic preference regarding bird names, but in his journals, Audubon capitalizes everything from Water to Supper, Evening to Eggs. In literature as in life, he embraced a personality that refused to be confined to the lower case.

Audubon’s prose has other, more vexing eccentricities. His punctuation and spelling, particularly in his journals, often jolt the reader into a double take, with some sentences requiring repeat readings to grasp their intent. As Sanders reminds readers, Audubon also wrote at a time when conventions of spelling were less uniform, so that even well-educated people such as Thomas Jefferson spelled erratically. The challenge leaves editors wondering when to revise Audubon’s jottings in the interest of clarity, and when to leave them unaltered as the markings of a distinct literary bird.

Audubon hired a Scottish naturalist, William MacGillivray, to help smooth out some of his English while writing the Ornithological Biography. A more intrusive editorial hand appeared after Audubon's death, when granddaughter Maria R. Audubon published a heavily censored form of his journals. According to naturalist Robert Finch, one of the challenges “of assessing Audubon’s status as a writer is the fact that much of his published writing is not actually Audubon's own words, but those of his collaborators and editors.”

Luckily, the unmediated Audubon endures in surviving portions of his original journals, as well as in his letters. “It is fair to say that Audubon was one of the great American letter-writers of the nineteenth century,” Finch has observed. “Certainly he was one of the most prodigious, and often under conditions that seem anything but conducive to extensive correspondence.”

In the Library of America collection of Audubon’s prose, Irmscher opts for the very lightest of editing, leaving Audubon’s words pretty much as they flowed from his pen. One of Irmscher’s objectives, apparently, is to remind the reader that for Audubon, English was a second language.

As an immigrant, Audubon brought an outsider’s perspective to many of his observations, and it’s this outside-looking-in sensibility that gives much of his writing its freshness and vitality. But juxtaposed against this sense of Audubon is a popular, alternative view of the naturalist as the quintessential American. On the day before the Fourth of July in 1812, Audubon became an American citizen, and one of his most memorable essays, “Kentucky Barbecue on the Fourth of July,” recounts a merry exercise in frontier patriotism:

In a short time the grove was alive with merriment. A great wooden cannon, bound with iron hoops, was crammed with homemade powder; fire was conveyed to it by means of a (powder) train, and as the explosion burst forth, thousands of hearty huzzas mingled with its echoes. From the most learned a good oration fell in proud and gladdening words on every ear, and although it probably did not equal the eloquence of a Clay, an Everett, a Webster or a Preston, it served to remind every Kentuckian present of the glorious name, the patriotism, the courage and the virtue of our immortal Washington.

In his subsequent travels back to the Old World, Audubon took great pains to groom his image as an archetypical man of the American frontier, using his swashbuckling persona to create interest in his work. Like most masters of publicity, he wasn’t above bending the truth to help his case. Rhodes’s comparison of Audubon’s life with the work of a novelist is particularly apt because Audubon’s personal narrative sometimes lapsed into fiction.

He famously painted a rattlesnake preying on a mockingbird’s nest, although rattlers aren’t widely known for climbing trees. In a later scientific paper that proved controversial, Audubon made even more flamboyant claims about rattlesnakes, sharing a tale about a farmer dying of a rattlesnake fang embedded in his boot, a tragedy followed months later by the deaths of the farmer’s two sons after they had taken turns wearing their father’s boots. As Audubon scholar John Chalmers has observed, “Audubon was not one to allow strict accuracy to interfere with a good story.”

Equally suspect is an essay supposedly based on Audubon’s Louisiana travels in which he brags about reuniting a runaway slave family with its previous owner, resolving the case to both the slaves’ and the owner’s satisfaction. Audubon biographer William Souder wonders how Audubon would have had the social standing to pull this off. Audubon’s suggestion that the slaves were happy with their return also seems implausible.

The story suggests that Audubon wanted to appear tolerant, although in matters of race, he was very much a man of his time and place. He had owned slaves himself and expressed disgust at racial intermingling he had observed in New Orleans.

Even though he would be invoked as an environmental icon after his death, Audubon had a mixed record on ecological stewardship. He often shot more birds than he could either eat or use as art specimens, and his complicated response to concerns about bird populations is perhaps best expressed in a March 16, 1821, journal entry from New Orleans. In the passage, Audubon chronicles the passage of “millions of golden plovers” coming from the north—and their widespread slaughter by hundreds of local hunters: “a Man near where I Was seated had killed 63 dozens—from the firing below & behind us I would Suppose that 400 Gunners were out, Supposing each Man to have killed 30 Doz(en) that day 144,000 must have been destroyed. . . .”

Audubon seems sobered by what he sees, although apparently, it doesn’t dissuade him from joining in the shooting. Significantly, the plover shoot, despite its scale, kills only a fraction of the birds that fly over, and to most nineteenth-century minds unversed in the nuances of wildlife management, that kind of plenitude must have seemed infinite.

Not everyone excuses Audubon’s hunting habits as a period pathology, and some critics maintain that he should have known better. But the imperfections of the man make him all the more human—and all the more relevant to contemporary readers of Audubon’s work as they consider their own foibles. His conflicted vision of the natural world is not without its modern parallels.

The power of Audubon’s writing—and its abiding complication—is that it so perfectly reflects the vision of his art. Audubon’s journals and essays, like his famous pictures, brim with color, shimmering detail, and an unapologetic sense of theater. Audubon wasn’t flawlessly accurate as an artist and a writer, but he was endlessly attentive, which is no small thing. There’s often a telegraphic urgency in his journals, as if he’s racing to get everything down before it fades from view. He was, like Henry David Thoreau and John Muir, a self-appointed recording secretary of creation, his sentences bristling with the energy of a reporter on deadline.

In his prose as in his paintings, it’s the incidental details that shake us awake, as in his mention of a clever way to catch hummingbirds. Pour sweetened wine into the cavities of flowers, says Audubon, and the tiny birds “fall intoxicated.” Nearly two centuries after he penned that musing, it intoxicates the reader as well.