“Let me make the songs of a nation, and I care not who makes its laws” is a somewhat paraphrased proverb ascribed to the eighteenth-century Scottish patriot Andrew Fletcher. Fletcher’s intent was to say that as long as there was Scottish music there would be a Scotland, English political machinations notwithstanding. The idea that music powerfully expresses national identity was seemingly self-evident enough that it demanded little serious attention in the century and a half after Fletcher. Only at the end of the nineteenth century did German musicologists begin systematically collecting and publishing their nation’s music in editions they called, appropriately, Monuments. Within a few years, scholarly projects were under way throughout Europe to erect musical monuments to national identities.

Although “What is America’s music?” is a question that has been around since “Yankee Doodle” rang triumphantly over the Surrender Field at Yorktown, answers have not been easy to come by. A national musical identity fashioned through immigration, importation, and the indigenous promises more of a richly pieced quilt than a granite monument.

But in the early 1980s a group of musicologists and musicians concerned with American music gathered and tackled the question directly. The result was a decision to publish a multivolume Music of the United States of America (MUSA), with special support from the American Musicological Society and the National Endowment for the Humanities. The plan called for a forty-volume set that would ambitiously reflect the wide breadth of the nation’s music, while maintaining a balance among styles, eras, musicians, and performing forces. Each volume would be peer-reviewed, scrupulously edited, and prefaced by an extensive introduction that contextualized the music. To ensure the highest quality of work, editors would work with MUSA’s editor in chief and its executive editor, all to be overseen by an appointed Committee on the Publication of American Music (COPAM).

To date, thirty-one MUSA volumes have been published. The range of music is quite extraordinary: Irving Berlin songs; psalmody; a composition based on hitchhiker inscriptions; Fatha Hines, Charles Ives, and John Philip Sousa; music from a powwow; women composers Ruth Crawford, Amy Beach, and Florence Price; Yiddish musical theater; Shuffle Along; jazz, chamber music, John Cage, opera . . . with blues, Hawaiian songs, hymns, Mexican-American music, British-Irish-American folk songs, and much else in the pipeline.

Each volume has a compelling story about how and why it came about, which often tells of long hours in a dusty archive. MUSA 22 is different from most in that its genesis was in a family tradition of bedtime reading with my eight-year-old son. Sam and I tended toward books in a series, since that helped with the “What next?” question. There are eight Little House books by Laura Ingalls Wilder, so we started in on Little House in the Big Woods. We both enjoyed it and decided to keep going. After completing Little House on the Prairie (the third book) we were hooked.

The father-in-me delighted in the stories of the frontier and Sam’s pleasure in them, and, surprisingly, the musicologist-in-me also had something to chew on. The family patriarch, Charles “Pa” Ingalls (1836–1902), was an able provider, but he was also a musician. Pa was always grabbing his fiddle and playing for family and friends or rustling up a family songfest, for music was a commonplace in and around the Ingalls family. As a song came up in a book, I’d sing it when I knew it, or make it up if I didn’t. Turned out that my powers of invention were increasingly stretched, for there are lots and lots of songs woven into the stories.

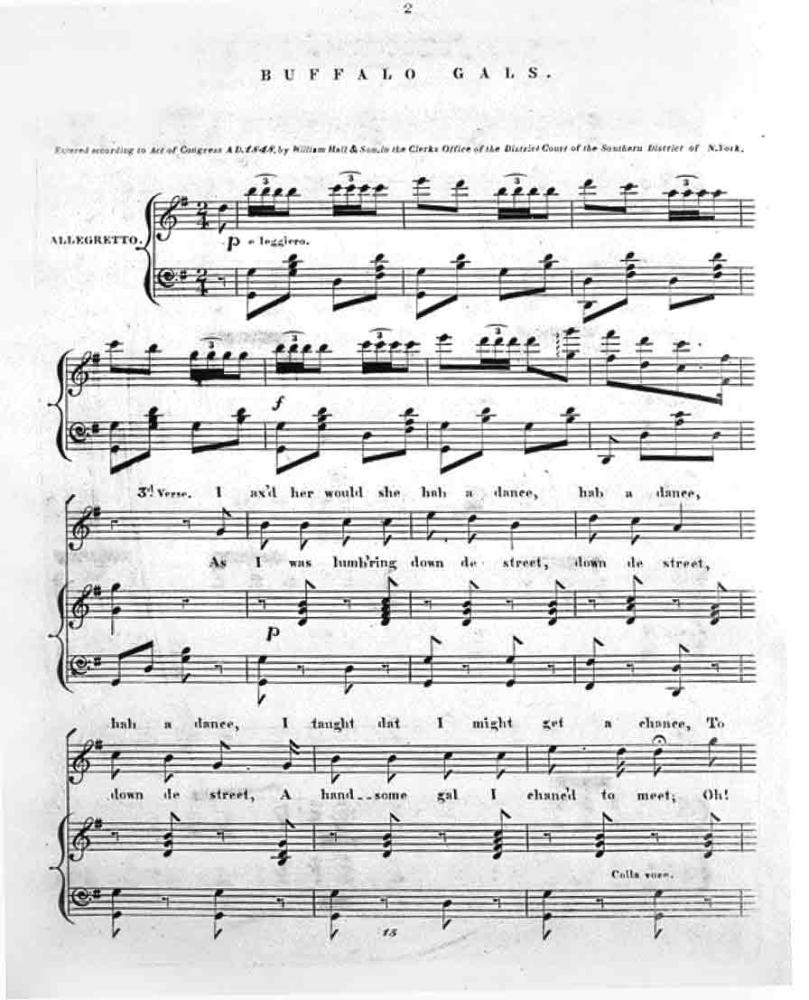

Curiosity led me to draw up a preliminary list of the songs and tunes in the books. To my amazement, there were more than 120 of them (127 in the final count). And evidently the centrality of music-making to the stories was a conscious decision by Wilder and on her mind from the first. Preliminary to her first published book, she wrote a quasi-autobiography titled Pioneer Girl that referenced far more songs than in any of her subsequent books. A note in a margin even made her intention clear—“If you want the spirit of these times, you should read over these old songs.” Since the Little House books are based on real people whose spirited lives are fairly accurately represented by Pa’s daughter Laura, I became convinced that the books, in addition to being great stories, manifested a contextualized anthology that traced music-making in a real frontier American family and community.

But, spirit and scholarly queries aside, what Sam and I wanted most immediately was to hear the songs. That was not easy, for no one seemed to have recorded “the music of the Little House books.” So we did. I established Pa’s Fiddle Recordings in 2004 and set about producing recordings of many of the Little House songs. To date, four CDs, a PBS hourlong special concert (Pa’s Fiddle: The Music of America), an NPR program featuring Riders in the Sky, countless interviews, concerts, awards, articles, grade school presentations, a full set of music books, and more have resulted from that decision. Many of the great old American songs in the Little House books live again, ready to be heard and enrich the lives of American children (and parents and grandparents, too).

The idea to prepare a scholarly edition of the Little House music came along later, once I realized fully that Wilder’s musical anthology was real, that it was virtually unique, that it placed family and community at the center of music-making, and that it mattered to millions of people the world over. It struck me that here was an opportunity to connect what I was qualified to do with the interests of both scholars and the public. Furthermore, Wilder’s anthology was widely representative of music in late nineteenth-century America: parlor songs, stage songs, minstrel show songs, patriotic songs, Irish songs, hymns, spirituals, fiddle tunes, singing-school songs, folk songs, Christmas songs, catches and rounds, and more were all there. Convinced a MUSA edition was a viable idea, I drew up a proposal, submitted it to COPAM, and was joyous when it was accepted. A fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities then enabled an unencumbered stretch of time to work on the edition.

Published in 2011, The Ingalls Wilder Family Songbook contains scholarly editions of 126 songs. (“The Red Heifer,” which Wilder claimed Pa played, seems not to have survived.) MUSA 22 was prepared so that readers and musicians might learn what the frontier Ingalls family sang and played, and develop an appreciation of how families—even all communities and nations—express themselves through music. Wilder skillfully inscribed compelling narratives that provide a ready context for loving the music that was the accompaniment to her life, time, and place. By having the Songbook’s music collected and performed again, my intention is that an important American musical heritage will be re-voiced, giving rise to a new engagement with “the spirit of [all] these times.”