“Do you know what a pie safe is?” Ken Burns asked me during a recent phone conversation.

It was early March, and Burns and I were talking about his 1994 documentary series Baseball, which is being reissued on DVD and Blu-ray in a newly restored version this spring.

Burns mentioned that he had walked into his dining room, where, over a quarter of a century ago, he had conducted the last of four interviews with one of the stars to emerge from the series: the great Negro League first baseman and manager Buck O’Neil, who died in 2006. Burns said he thought of O’Neil almost like a father figure.

“That was the background [for] the last, very warm interview of Buck,” Burns said. “You can make out the faint details—particularly in this new version—of the pie safe, which I am looking at.”

It seemed oddly fitting that Ken Burns, chief cinematic chronicler of American life, should bring up something as quintessentially American as a pie safe in the context of a conversation about a sport as typically American as baseball.

“It’s an utterly American game,” said Burns, who acknowledges baseball’s British antecedents—rounders and crickets—but insists that once Americans got ahold of some of the basic ideas, it became something else altogether.

“It’s the only game in which the defense has the ball and the only game in which the person scores, not the ball,” he said. “That, and 10,000 other things, make it the greatest game ever invented.”

Yet, 27 years after its debut, Burns’s Baseball—the restored version of which will be available June 8—endures not just because of our sentimental attachment to the game itself but because of the countless themes, stories, and personalities that spring from it.

Most of the time, Burns embarks on documentaries knowing little about a given topic other than that it is worth pursuing. When he came up with the idea to make a film about the national pastime, however, he thought he was on unusually solid ground.

“I remember my dad calling me down—he’s talking with some friends—and saying, ‘Son, what’s Roberto Clemente hitting?’” said Burns, a noted fan of the Boston Red Sox. “‘.334, Dad.’ Because I knew all that stuff.”

Yet, by his own admission, there were huge gaps in his understanding of the social context of the game. “I knew nothing about the whole history of it—the nineteenth-century so-called ‘gentleman’s agreement’ that excluded Moses Fleetwood Walker and Bud Fowler and other African Americans who were playing at what was the equivalent of the major league level,” said Burns. He was referring to the “color line” that blocked Black players from major and minor league ball clubs and continued until Jackie Robinson’s emergence as a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

Burns embarked on the project, which received substantial support from NEH, on the heels of his 1990 documentary series The Civil War, which, at nine hours, was an epic in itself. Lynn Novick, who later became a co-director on many Burns projects, served as a producer on Baseball. “He didn’t want to be pigeonholed as the war guy,” Novick said. “It had the potential, just by the very nature of the topic and our taking it on, to suggest that history wasn’t just politics and war.”

Plus, there was an appeal to a subject that was surely more modest—less sweeping, more containable—than the project that preceded it. “We just assumed that Baseball would be this lovely sort of tiny sorbet course after the massive Civil War series,” Burns said. “What I didn’t understand is that it was the sequel to The Civil War.”

Baseball would be about baseball only in a superficial sense. “We kept using the metaphor of a Trojan horse,” Novick said. “Through the story of baseball you can hook people with this surface-level story of these great heroes, and teams winning and losing, and people accomplishing great things.” Just below the surface, however, were the same issues that coursed through other aspects of American society, including race.

For his part, Burns views Robinson’s barrier-breaking career as one of the signal events in the history of civil rights since the Civil War. “The first real, national progress in civil rights was when Jack Roosevelt Robinson, the grandson of a slave, made his way to first base at Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947,” he said. “That was before Rosa Parks had refused to give up her seat. . . . It was before the integration of the military. It was before Brown v. Board of Education.”

Race was one of the dominant themes drawn out in the making of Baseball, but it wasn’t the only one. Over nine episodes, structured as innings, the series considered labor history, capitalism, and urbanization. “Through the prism of baseball, you can see all these different themes reflected,” Novick said. “Unlike The Civil War, it wasn’t going to be an epic tragedy, though there are many tragic stories in it.”

Baseball had its premiere amid one of the sport’s low ebbs: the 1994–95 strike. That work stoppage scrambled the planned publicity tour, which would have taken Burns and company to every city with a major league team. The filmmakers were worried that angry fans would be, at best, uninterested in a series about a sport that had, once again, become contentious.

“Why would somebody want to watch 18 hours on the history of something that they now hate?” Novick said. “It was beautiful to see that the exact opposite happened: The series filled a void.” Despite the length of the series, Burns said that the criticism he received usually revolved around what was omitted. “We were the only game in town,” Burns said.

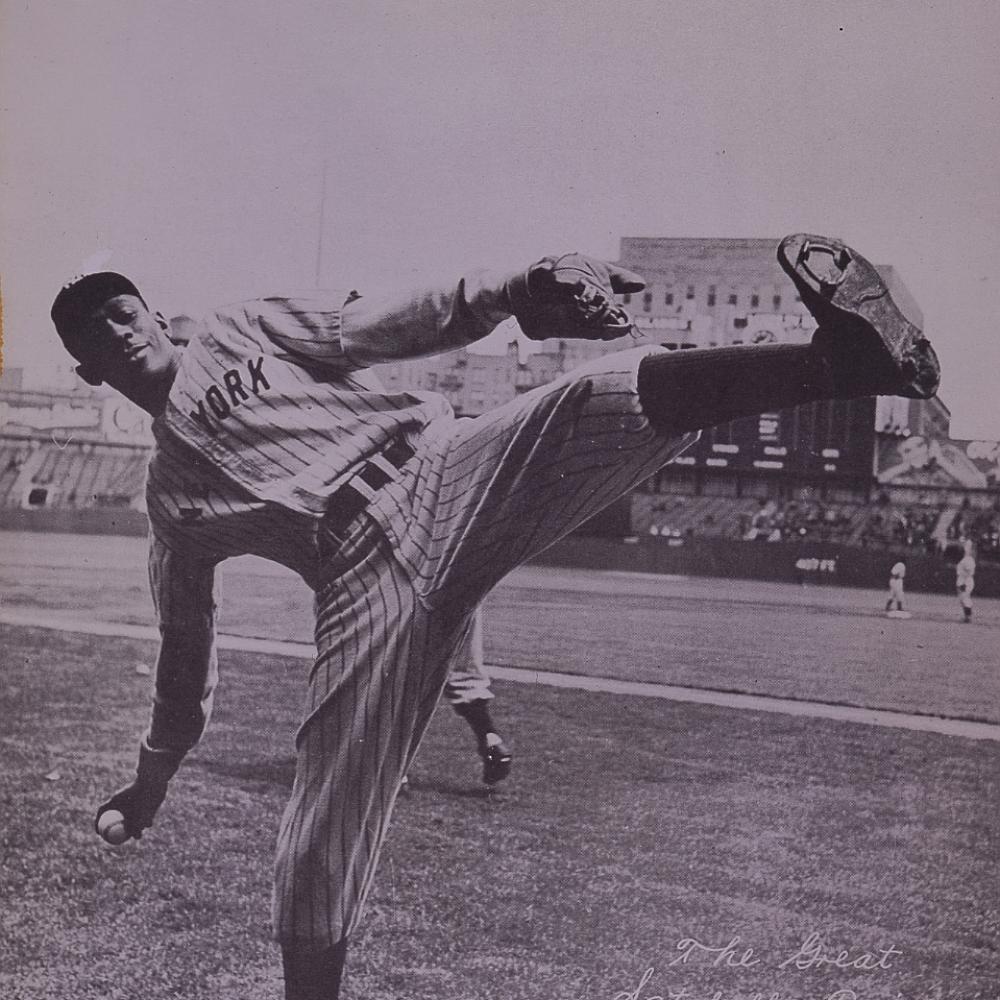

As is typical of his style, Burns lingered on still photographs and included plenty of archival film, but the interviews animated the series—and not just with talking heads like George Will or Billy Crystal, but players like Buck O’Neil, who, thanks to the documentary’s popularity, found himself a star once more. “That was just a great reminder of the power of our medium,” said Novick, who first interviewed O’Neil in his home in Kansas City. “Buck just lit up the screen—he lit up our room, he lit up the world—with his spirit and generosity and just humanity.”

Novick, who in 2010 co-directed with Burns a follow-up series, The Tenth Inning, said that baseball provided new immigrants with “a way into being American.”

“We are doing a film right now about America and the Holocaust, and I interviewed a refugee who came here from Germany as a teenager,” Novick said. “The things that helped him assimilate were jazz and baseball. He’d heard of Babe Ruth before he got here, and he moved to St. Louis and he was just obsessed with baseball.”

Does the sport remain as integral to the American experience as it once did—even as recently as 1994, when the series sparked the inner infielder in all of us? “Just to be blunt, the country is evolving into a much more multicultural and diverse and inclusive place, and I don’t think the baseball establishment has really figured out what to do about that,” Novick said.

Yet Burns is not done with baseball: The recent restoration—involving the repair, cleaning, and scanning of some 90,000 feet of 16mm film negative, overseen by Florentine Films post-production supervisor Daniel J. White—is said to look spectacular. And Burns even teases a potential third follow-up film on the sport—an eleventh inning, so to speak.

“I foolishly promised that if the Cubs ever won the World Series again, I would do it,” he said. “Of course, now the Cubs have won, and I’m several years out of that. My problem is just bandwidth. I’m working on nine films, all going at once.” Adopting a baseball term, he said he might “farm out” the project to a colleague. “I can be the granddaddy of it.”