The southern plains could have stayed what they always had been: an expanse of grass—one hundred million acres of buffalo grass, western wheatgrass, blue grama, and hundreds of other species. That was what the environment could support, flora-wise.

Semiarid, constantly windy, and prone to droughts—with long dry spells coming along every twenty years or so—the grasses were what kept the land together, what kept it from deteriorating into outright desert. Their tangled roots held the topsoil in place, prevented it from blowing away and exposing the dense layer of hardpan underneath. But so much rich earth, left to the good graces of nature, is hard to resist. And in the late nineteen-teens and throughout the twenties, the grass was dug up and plowed over and the churned soil left behind planted in wheat, a booming crop at the time. It was, as Oliver Edwin Baker of the Bureau of Agricultural Economics put it in 1923, “the last frontier in agriculture”: sodbusting the ancient Plains for a buck—and there were plenty of takers.

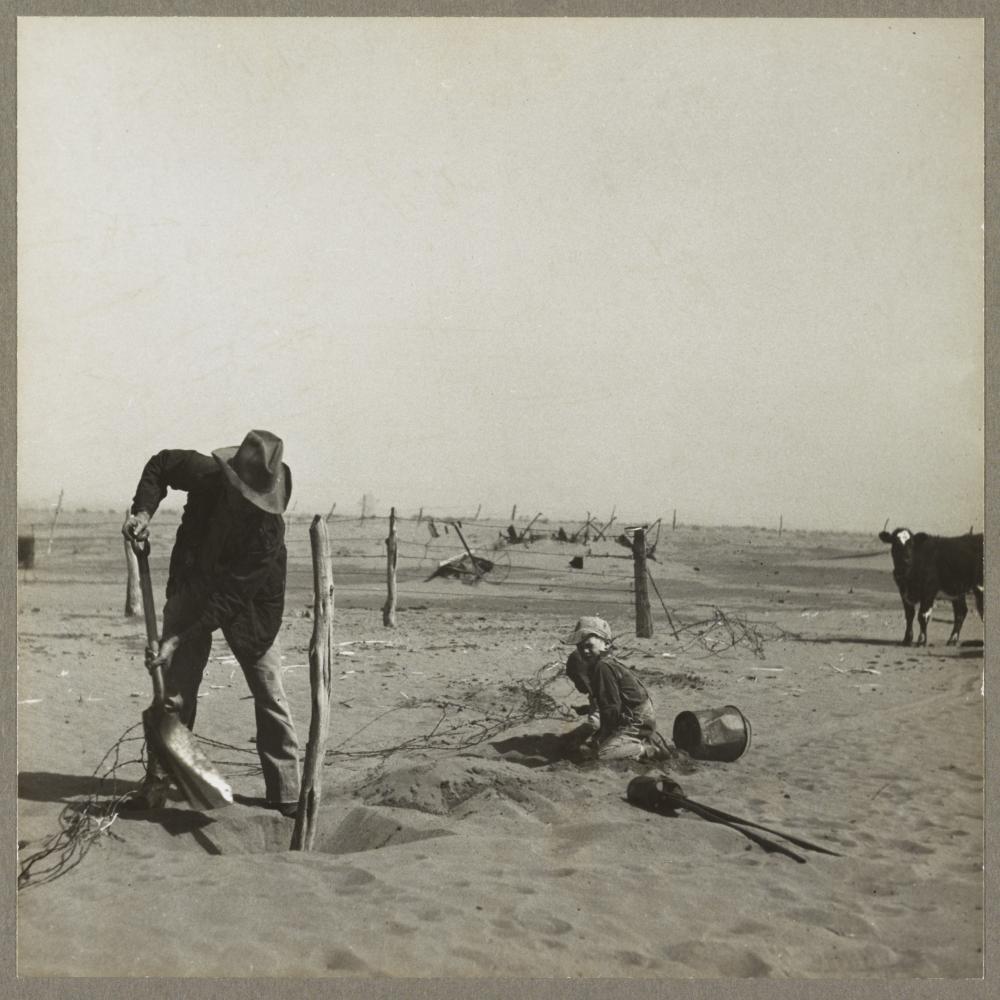

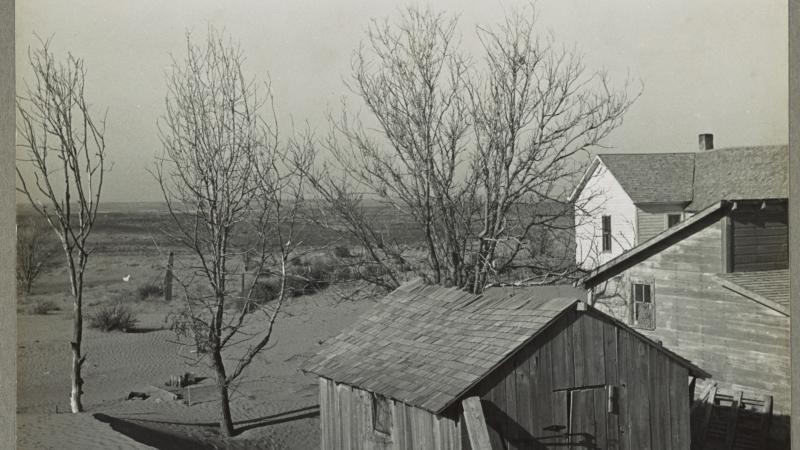

What followed, however, when a decade-long drought hit in 1931, was interpreted as Biblical: a nexus of Old Testament-worthy plagues that left people of the Plains wondering if God had abandoned their country, reneging vengefully on the promise of man’s dominion. The loosened soil, now dry and free to blow with the winds, became massive dust storms that suffocated cattle and sickened children; there were swarms of pests—jackrabbits and grasshoppers—that consumed anything even marginally edible in their path; and, of course, without rain, absolutely nothing grew. Bereft of its grasses, the land was wrecked, not only unfarmable, but brutally inhospitable, with dirt drifts that could whip up and kill you. To protect their eyes and lungs, people wore masks that made them look like they belonged on a World War I battlefield. To protect their fields (if they were lucky enough to grow anything), they sprayed them with cyanide. To feed their kids, they sold their starving cattle to the government for a dollar a head and watched them be destroyed. To control the rabbits, they organized community picnics that culminated in bloody clubbing sprees, the carcasses left to waste in piles. This, in its broadest outlines, was the strange, self-blighted world of the Dust Bowl, a shifting zone of catastrophes (defined by what counties in the region happened to be suffering most at a given time) so sweeping and destructive that they beggar description, if not belief. It is also the world of Ken Burns’s latest documentary.

Dust Bowl is “a Ken Burns film” in what might by now be called the traditional sense—that is to say, a beautifully wrought, latitudinous, and, at the very least, aspirationally definitive work of filmic nonfiction, right at home among the documentarian’s prior oeuvre. Like Baseball, Jazz, The Civil War, or just about any other work from Burns’s long filmography, it has the feel of a history proper. There are old photographs and grainy footage; contemporaneous accounts from magazines, newspapers, and correspondences; and a small cadre of talking heads (most of the professorial variety)—all drawn seamlessly together, as if the past and its detritus came ready-made for the screen. But for all the archive-culling and careful scholarship that makes it so quintessentially Burnsian, Dust Bowl is also, at its core and at its most compelling, a subtly different sort of animal from those that came before it. The hallmarks of Burns’s style don’t form the base of the film so much as its buttresses—the necessary but unmistakably peripheral materials that give shape and place to the raw stories of its real stars: a few men and women who, more than seventy years ago, as boys and girls, witnessed firsthand the worst manmade ecological disaster in American history. Tapping their childhood memories, Burns’s vision of the Dirty Thirties departs ever so slightly from the sense of staid authority that his viewers have come to expect and takes on something of the haunting quality of a remembered nightmare: visceral but vague, fragmented, and, at times, almost unreal.

It is a wholly appropriate approach to the terrors of the Dust Bowl. Consider: What do three hundred fifty million tons of airborne dirt, blown up on sixty-mile-an-hour winds and crackling with electricity, look like? How does it feel to watch that cloud roll in? To be caught up in its abrasive, blinding rage? Measurements and meteorological data, film and still photographs, even eyewitness reports can only suggest so much—and Burns, deft storyteller that he is, knows it. He knows that, of the resources available to him, it’s the child’s-eye view, a naive and poignant focus on the so-called small picture, the apparently miscellaneous detail that all but magically gives expression to whatever is unfathomable beyond it. When, in the film, Robert “Boots” McCoy recalls the first big dust storm to rip through the Plains, it isn’t his description of the black blizzard itself that hits home (“it was just like midnight in the middle of the day,” he says, “just like midnight with no stars”), but the vignette with which he wraps up the experience of having a mountain-range worth of earth envelop everything around him: “Mother would pray about it, you know. And us kids”—he means him and his elder sister—“were little. And we stayed pretty close to Ma, I can guarantee you.” No fact or artifact could make the storm any more visible, any more real, for the viewer than the act of sympathetic imagination that it takes to conjure an image of this mustachioed, older gentleman as a kid, huddled against his praying mom as the dark dirt blasted their home. It is an image that sticks. And it sticks because it makes the mass of the storm intimately intelligible.

Again and again, the survivors interviewed in Dust Bowl remind us that they witnessed the hard times on the Plains as children, knowing nothing but “a brown world,” as one puts it, and trying, as best they could, to make sense of the overwhelming hardship, grief, and courage that surrounded them. Adult anxieties linger at the edges of their memories—failed crops, repossessions, the possibility of starvation, the shame of relief, the escape of suicide—but those weren’t the kinds of troubles that, back then, they were prepared to fully process. What they remember are evocative slivers of that reality. They remember when dad killed the family’s calf (the children, their father knew, needed its mother’s milk just to stay alive), and the tough chore of trampling thistles (the only food left to feed the cattle), and the sight of a red morning sun, which, father said, augured a “bad day” (i.e., dust-storm weather). That their versions of events are from childhood memories takes nothing from their historic value. It is only a different history, metonymic and, set within the context that Burns and his scholars provide, all the more powerful for it.

Make no mistake: The film doesn’t dodge the tough stuff. The children of the Dust Bowl saw things that no one, no matter what their age, should see. And they are as capable as any witness of telling those things with devastating directness. Calvin Crabill, for instance, saw in action the U.S. government’s plan to stabilize the price of beef (the Depression was on, too) and lend a hand to the Plains farmers: Buy up emaciated, worthless herds of cattle and kill them. “What they did,” he says, “was they took a bulldozer and made a mammoth ditch, a mammoth ditch, and drove all the cattle down in there. And then there were men above with rifles, and I would say maybe ten or twenty men with rifles, and they shot the cattle.” The slaughter is represented in the film by the sound of gunshots. “I’ll never forget,” he continues, “standing there as a little boy. I was probably eight or nine years old when they started shooting those cattle. It’s a sight to this day that—the average person couldn’t stand it. But, as a little kid, it was very rough, because that was our stock.”

And the most affecting moment in the film comes from Floyd Coen, whose little sister, like hundreds of others, succumbed to what doctors at the time called “dust pneumonia,” a respiratory illness caused by tiny inorganic particles in the windblown dust. She died in one room of the family’s two-room house, he tells the camera, while he lay sick with the same illness in the other. The doctor brought the toddler’s body out on a table leaf, for everyone to see one last time, before carrying her off to the mortuary. “That was the hardest thing on me,” Coen says, “and still is. She was such a perfect little thing.” The man’s face registers such fresh emotion at the recollection that it’s hard to watch.

But we do watch. Because, in the grand scheme of Burns’s film, it is only a flicker and then gone—just enough pathos to register the human consequences of tearing up the grasslands; but not enough to come off like some kind of over-impassioned indictment of those who, out of ignorance or greed or hubris, did the actual tearing. The Plains, these children’s stories movingly (if only implicitly) argue, should have been left a profusion of grass—if they had, growing up on them would have been less difficult, less painful. But the kids were blameless of that mistake. And their blameless suffering makes them a resonant symbol of those blameless sufferers who might come after them. That is precisely where Burns ends his four-hour trek: with a worry (not quite a warning) about the future of the Plains, a worry that comes with its own brief history and bridges the gap between the Dirty Thirties and today.

New Deal efforts at soil conservation brought back the land. When the rains came back in ’39, and dust storms started to settle down, farmers on the Plains turned to the Ogallala Aquifer, the 174,000-square-mile water table beneath them, to satisfy their crops’ needs. In a region with so little and such unreliable rainfall, it made sense: All the water that they could ask for was right there, under their feet, and the technology to get at it finally was affordable. Wells started cropping up everywhere, some feeding crops that required more moisture than the wheat lost only a decade or two earlier. What seemed like a good idea at the time “was the beginning of a bad idea,” said one old-timer at the close of the film. The Ogallala recharges, but slowly, capturing only 0.024 to 6 inches per year, depending on the specific area in question: much too slowly to keep up with the demands of the irrigation wells, which now number in the hundreds of thousands. Just how much water the aquifer holds is difficult to know, but its volume has been dramatically drawn down since 1950. At the present rate of depletion, the aquifer could, at some point, be pumped dry. And when that happens, the Plains, the people who live there, and their children could face the possibility of another Dust Bowl.