Keeping Radio Haiti’s Memory Alive

This post is guest authored by Laura Wagner and is a follow up to our 2016 blog post Tune In Tuesdays: Voices of Change: Preserving Radio Haiti, highlighting NEH Preservation and Access projects to preserve audiovisual materials. From 2015 to 2019, Wagner was the project archivist for the Radio Haiti Archive at Duke University’s Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. She holds a PhD in cultural anthropology from UNC Chapel Hill, where her research focused on displacement, humanitarian aid, and everyday life in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. She is now the team lead for Haitian Creole at Respond Crisis Translation. She is also a nonfiction writer and novelist who is currently writing a book about the history and legacy of Radio Haïti-Inter.

“It’s our duty — it is mine — to try to keep memory alive.”

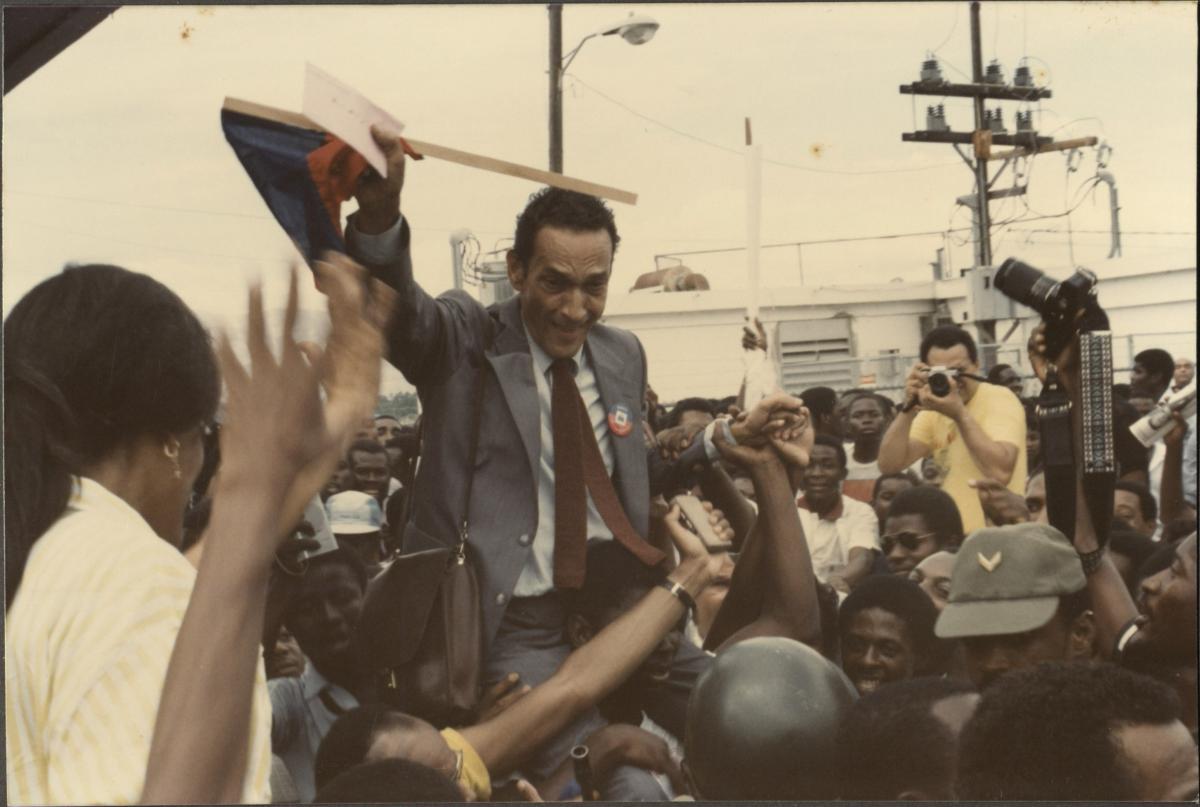

Jean Dominique, a journalist and activist, spoke these words during the summer of 1999, standing on the roof of his station Radio Haïti-Inter in Port-au-Prince. I found the interview in the raw footage of Jonathan Demme’s documentary The Agronomist, which would one day become part of the Radio Haiti Archive. In the grainy video, Dominique, wearing a white guayabera and khaki pants, seems impatient. He was a news editor with a radio station to run, and although he was a charismatic public figure and Haiti’s most recognized journalist, he wasn’t interested in being a star. When the interviewer asks how the Duvalier dictatorship stayed in power for so long, Dominique answers, “Force, blood, tears, executions, extortion, Fort Dimanche [an infamous political prison], etcetera!” The interviewer asks if young people understood the history of the regime. That’s when Dominique spoke of his duty to keep memory alive.

Less than a year after the interview was recorded, Jean Dominique would be gone—assassinated in Radio Haiti’s own courtyard, another memory to be preserved.

Radio Haïti-Inter was the country’s most prominent independent radio station. From the early 1970s until 2003, it fought for democracy and human rights, revolutionized media in Haiti, and created space for voices of ordinary people who had been excluded from political and cultural discourse and denied information and power. The station reported in Haitian Creole (Kreyòl), the language of all Haitian people, as well as in French. In 2014, Michèle Montas—Jean Dominique’s professional partner and wife—donated more than 1,600 open-reel tapes, more than 2,000 audio cassettes, approximately 80 linear feet of paper records, and a handful of other media to Duke University’s Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library under the condition that they be digitized and made available to as many people as possible in Haiti. Today, the Radio Haiti Archive is a free, publicly accessible, trilingual digital collection. Its more than 5,300 audio recordings represent an unparalleled archive of late 20th-century Haitian history.

None of this would have been possible without the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities in the form of two Humanities Collections and Reference Resources grants from the Division of Preservation and Access (PW-226836-15 & PW-259094-18). The first, Voices of Change: Preserving Radio Haiti (2015-2017), allowed us to inventory, restore, digitize, and create initial descriptions of Radio Haiti’s open reels and cassettes. Many of the tapes were extremely fragile, damaged not only by heat and humidity but also from the same repression that twice forced Radio Haiti off the air and into exile and eventually to close for good. The 88 most damaged tapes were remediated and digitized through additional funding from the CLIR Recordings at Risk program.

The second NEH grant, Voices of Change II: Bringing Radio Haiti Home (2018-2019) allowed us to create detailed trilingual (Haitian Creole, English, and French) metadata and narrative descriptions of each and every one of Radio Haiti’s recordings. These audiovisual materials are now fully searchable and publicly available to people all over the world via the Duke Digital Repository (DDR).

Creating a comprehensive digital platform was the first step in the digital repatriation of the Radio Haiti Archive. Physical repatriation is not feasible due to the political and infrastructural situation in Haiti—and much of the physical media is too damaged for anyone to use it again. While having the Radio Haiti audio available online via the DDR is crucial, our objective has always been to make the materials as accessible as possible to people in Haiti and the Haitian diaspora. This has also included experiments in putting Radio Haiti material on YouTube and the Internet Archive.

One year into the project, in 2016, I went to Haiti with 1,000 flash drives, each containing around thirty selected recordings of Radio Haiti content to distribute to community libraries, research libraries, archives, schools and universities, grassroots organizations, community radio stations, and cultural institutions. Each flash drive was printed with Radio Haiti’s famous logo and a link to the permanent Radio Haiti collection guide. I encouraged people to distribute the flash drives widely and to copy them for others.

Two years later, I returned carrying a smaller number of flash drives, each of which contained approximately 500 Radio Haiti recordings and a trilingual spreadsheet of detailed metadata. I distributed these to our partners and contacts in Haiti, such as the Fondasyon Konesans ak Libète (FOKAL) and their network of community libraries, the Bibliothèque haïtienne des Frères de l'Instruction Chrétienne at Saint-Louis de Gonzague, and media outlets like AlterPresse and Haiti’s nationwide network of community radio stations, the Sosyete Animasyon ak Kominikasyon Sosyal (SAKS). Having “hard” copies of the digital archive would allow students, researchers, and community members to use the materials regardless of whether they had a fast internet connection, or any internet connection at all. Meanwhile, AlterPresse and community radio stations could use the USB drives to rebroadcast Radio Haiti materials on the airwaves today, plumbing the archives to commemorate anniversaries or to show a throughline between the past and the present.

The Radio Haiti project wrapped up when our NEH funding ended in the summer of 2019. We had planned the final digital repatriation once we had completed the description of the entire collection. I had hoped to visit libraries, schools, and radio stations in Port-au-Prince and facilitate workshops on using the archive. I’d planned to go to Gonaïves and make sure that the survivors of the Raboteau massacre knew the archive was theirs, and to Jean-Rabel, where members of Tèt Kole and their descendants still commemorate the resistance and repression of 1987, and to the Fawès, where people made offerings to the spirits before risking their lives upon the sea. Maybe I could even go to the Dominican Republic and bring the archive to the bateyes. But by the fall, widespread protests against Haiti’s government, accompanied by a general sense of what Haitian people call ensekirite, had made much of the country inaccessible and everyday life unpredictable. Roads were blocked, schools and institutions closed. As the situation in Haiti (mounting violence by government-funded gangs, a presidential assassination, a major earthquake) and around the world (the COVID-19 pandemic) grew more dire and uncertain in the months and years that followed, the final repatriation was put on indefinite hold. We cannot yet repatriate Radio Haiti’s archive because the very issues that Radio Haiti reported on for 30 years—government corruption, ensekirite, the exclusion of the majority of Haitian people—are still happening.

Nonetheless, Radio Haiti’s legacy continues to spread. Working on and discovering the archive was a formative experience for the project’s undergraduate and graduate student assistants, including Tanya Thomas, Krystelle Rocourt, Eline Roillet, and Catherine Farmer. Scholars like Ayanna Legros and Jennifer Garçon have used the archive in their research on transnational Haitian radio activism. AlterPresse’s radio station AlterRadio continues to air selections from the archive. As for me, after four years as the full-time Radio Haiti archivist, I am still thinking and working with the archive as a writer, researcher, occasional translator, and collaborator on several creative projects. Scholar-performer Mario Lamothe and I used the Radio Haiti collection to co-create a piece about the experiences of Haitian detainees in the early 1980s, which Lamothe performed in 2019. In early March 2020, singer-songwriter Leyla McCalla’s “Breaking the Thermometer to Hide the Fever”—which draws on the Radio Haiti collection and for which I served as dramaturg, translator, and research consultant—debuted as part of Duke Performances’ “From the Archives” series. (The album dropped in May 2022!) To accompany the debut, I designed and mounted “Radio Haiti: Three Decades of Resistance,” which, in addition to a traditional exhibition gallery, also invited people into a Haitian “home” to listen to selections from Radio Haiti.

Since Radio Haiti was meant to be heard, I have begun working with podcast creators, including an episode of the NEH-funded podcast Subtitle called “The Language of the Outside People,” in which Michèle Montas and I discuss Radio Haiti’s on-air use of Kreyòl, as well as an ongoing collaboration with Patrick Jean-Baptiste’s Nèg Mawon podcast. And at present, I’m writing a book largely about Radio Haïti-Inter, its archives, and its echoes—tentatively titled We Sway, We Do Not Fall after the station’s motto, nou balanse, nou pa tonbe. Because it is my duty, too, to keep memory alive.