In this excerpt from Henry David Thoreau: A Life (University of Chicago Press, 2017), NEH grantee Laura Dassow Walls chronicles the turning point when Thoreau sold his first articles and began recording the observations that would make him famous. He was thirty years old, and, though not yet an established writer, he understood that “beauty & art” were his vocation.

In March 1848 came an unlooked for opportunity to explore that high vocation with Harrison Gray Otis Blake, the man who became Henry David Thoreau’s first real disciple. Harry Blake lived in nearby Worcester. As an 1838 Harvard Divinity School graduate, he had helped instigate and publish Emerson’s breakthrough critique of conventional Christianity, “The Divinity School Address.” In the ensuing firestorm, Blake had dropped out of the ministry and taken up teaching, often inviting Emerson to lecture in Worcester. Something Thoreau said caught his ear, and after reading, of all things, Thoreau’s obscure “Aulus Persius Flaccus,” Blake was inspired to write a fan letter: “I would know of that soul which can say ‘I am nothing.’ I would be roused by its words to a truer and purer life.”

Roused himself, Thoreau sat down at his green desk in the prophet’s chamber [Thoreau’s alcove at the head of the Emersons’ stairs] and poured out heart and soul. “I am glad to hear that any words of mine, though spoken so long ago that I can hardly claim identity with their author, have reached you,” he opened. “It is not in vain that man speaks to man. This is the value of literature.” In the rest of the letter, Thoreau explored his hopes, dreams, and philosophy; gave counsel; radiated wisdom; and yearned for a higher life. Never before had anyone triggered such a generous response from him. “I need to see you,” he closed. “Perhaps you have some oracles for me.” Blake did; he wrote back immediately. The two became lifelong friends, exchanging frequent visits and often traveling together. Many times Blake invited Thoreau to lecture in Worcester, often in his parlor, where Harry and his wife, Nancy, gathered their friends to listen and converse. Thoreau wrote fifty more letters to Blake, the last from his deathbed. Whenever a new one arrived, Blake would call together his circle—above all the philosophical tailor Theophilus Brown, who lived nearby—to read and weigh Thoreau’s words. In afteryears, Blake became his friend’s literary executor, and though, sadly, someone destroyed Blake’s half of their correspondence, he treasured Thoreau’s papers, publishing four volumes of excerpts from Thoreau’s Journal and creating his first modern audience—an audience that grows to this day. Such, indeed, is the value of literature.

What’s more, Blake gave Thoreau what he most needed: the conviction that he had something to say and an audience to whom he could say it. “Lectures begin to multiply on my desk,” he wrote happily to Emerson. He had brought away from Walden a whole stack of unfinished projects, including a complete first draft of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, a nearly finished draft of Walden, a rough draft of “Ktaadn,” and more—indeed, much of his life’s work. He took up each project in turn, polishing it and turning it loose in the world. At Walden, Thoreau had learned how to live a writer’s life; now at Emerson’s, he was living it still, surrounded by manuscripts in various stages of composition, a different project for every mood and interest, each one finding its unique voice and stance relative to the others and all of them together composing a literary ecology.

The one project Thoreau completed at Walden Pond was, in effect, an essay on how to write. The over-the-top pyrotechnics of Emerson’s Scottish friend Thomas Carlyle had intrigued Thoreau since he first encountered them at Harvard. Carlyle broke every rule Professor Channing ever prescribed and danced like the devil on the shards. In writing about Carlyle, Thoreau cared less about what he said than how he said it—that is, his “style,” meaning, Thoreau explained, “the stylus, the pen he writes with,” literally the point where a mind, in meeting the blank paper, meets the whole world. What was really at stake was Thoreau’s own pen, Thoreau’s own style. The essay he finally published, “Thomas Carlyle and His Works,” reads like a final exam in a long, self-taught course in how to stop sounding like a Harvard graduate, how to start reaching farmers and mechanics as well as preachers and professors. Old people, wrote Thoreau, shook their heads at Carlyle’s “foolishness” and “whimsical ravings,” but young people got it: his craziness was good plain English. Defending Carlyle gave Thoreau permission to sound like himself. “Exaggeration! was ever any virtue attributed to a man without exaggeration? was ever any vice, without infinite exaggeration? Do we not exaggerate ourselves to ourselves, or do we recognize ourselves for the actual men we are? Are we not all great men? . . . The lightning is an exaggeration of the light.”

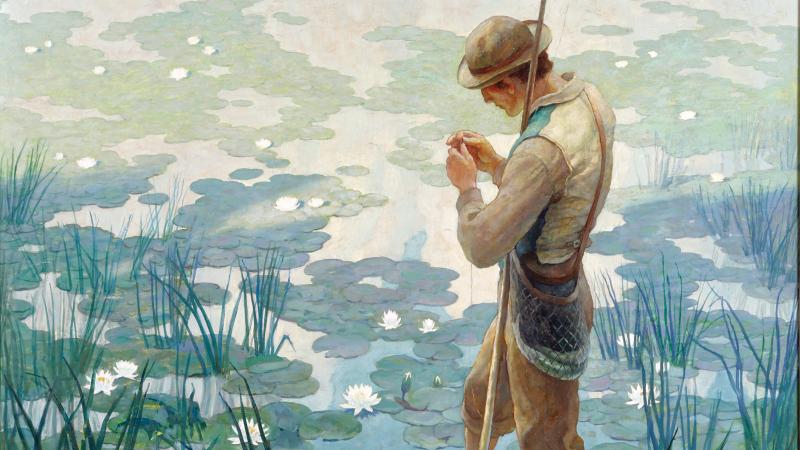

Best of all, Carlyle kicked philosophy out-of-doors, among the common people. Thoreau saw him as the hero of the workingman—as a workingman himself, toiling through the fog and smoke of London to earn the bread of life and share it freely with the poor, “the hero, as literary man,” who would not rest until “a thousand named and nameless grievances are righted.” Thoreau saw his opening here between Carlyle the literary hero and Emerson the idealist philosopher: Neither one spoke to “the Man of the Age,” to the life of the ordinary “working-man.” That would be Thoreau’s place—Thoreau the day laborer who could plow a field, swing a hammer, stone a cellar, reset a privy, or plant an orchard. Work! said Carlyle. “Know what thou canst work at.” But, Thoreau added—looking at Walden’s calm waters—he missed in Carlyle “a calm depth, like a lake” that would still that whirligig working mind, so one could think, and reflect, and “feel the juices of the meadow.” Speak of what you believe; speak out of your experience. “Dig up some of the earth you stand on, and show that.”

On February 4, 1846, Thoreau had banked his fire at Walden and walked into town to air his thoughts on Thomas Carlyle. His neighbors listened politely but protested that they wanted to hear about Henry Thoreau, not Thomas Carlyle. What was he doing out there at the pond? Was he lonely? Was he afraid? What did he eat? Thoreau wasn’t ready to answer them yet. Instead he polished up his Carlyle piece and sent it to Horace Greeley in New York—the first test of Greeley’s offer, made nearly three years before, to serve as Thoreau’s literary agent. Greeley was as good as his word. “Carlyle” was too long, he warned, and “too solidly good” for the masses, but still, Greeley placed it almost immediately in the upscale Graham’s Magazine after assuring the editors it was “brilliant as well as vigorous” and written by “one of the only two men in America capable of giving it.” It was a good match to one of the few journals that actually paid, although Graham’s delayed getting Thoreau’s essay into print until the following spring of ’47, and then forgot to pay him until Greeley, ticked, cornered the editors in person a year later with a bill for 75 dollars. Thoreau was overcome with gratitude to have such a champion. Emerson made sure Carlyle received a copy, which his distant friend read “with due entertainment and recognition” for Thoreau’s “most admiring greathearted manner.”

A long, heavy essay on Carlyle would hardly put Thoreau’s name in lights, but even here Greeley saw an opportunity. “Just set down and write a like article about Emerson,” he prodded, then another about Hawthorne, and so on. He’d pay 25 dollars for each one, sell them individually, then collect them into a book. It was a great plan—for someone else. After jotting a few notes about Emerson and Alcott, Thoreau wisely stepped back from writing exposés of his friends. Indeed, he was done writing about other men. Instead he would offer what he himself wanted of any lecturer: “a more or less simple & sincere account of his life.” So a year later, in February 1847, Thoreau banked his fire again, hiked into town, and stepped up to the podium to answer his neighbors’ questions: “Some have wished to know what I got to eat—If I didn’t feel kind o’ lonesome—If I wasn’t afraid—What I should do if I were taken sick—and the like. . . . After I lectured here last winter I heard that some had expected that I would answer some of these questions in my lecture.” It was an instant hit—“uncommonly excellent,” thought Prudence Ward. Henry was asked to repeat it the following week, but instead he gave a whole second lecture. Soon he had a trio of lectures he could mix and match, or give as a series. Eventually they became the opening chapters of Walden.

Reactions to the new Walden material were encouraging. Even skeptics “were charmed with the witty wisdom which ran through it all,” said Emerson. Abigail Alcott joked that “Mr. Alcott thinks we shall never be safe until we get a Hut on Walden Pond where with our Beans Books and Peace we shall live honest and independent”—then added, more seriously, “It is no small boon to live in the same age with so experimental and true a Man.” Prudence Ward was a bit more hesitant: “Of course few would adopt his notions—I mean as they are shown forth in his life.” Yet even she thought it was useful, and “much needed.” Walden was taking shape: edgy social satire, exaggerated for humor and sting, delivered neighbor to neighbor. “I trust that none of my hearers will be so uncharitable as to look into my house now,” at the end of a dirty winter, with “critical housewife’s eyes”—whose eyes did he catch just then?—“for I intend to celebrate the first bright & unquestionable spring morning by scrubbing my house with sand until it is white as a lily—or, at any rate, as the washerwoman said of her clothes, as white as a ‘wiolet.’” When Thoreau moved away from Walden to Emerson’s, he went back to work, polishing the early lectures into what he now envisioned as a second book, a sequel to A Week.

A winter lecture by Henry Thoreau was becoming a regular feature of Concord life. Once he was settled at the Emersons’, Thoreau unpacked the manuscript of “Ktaadn” and got it ready for a test run, soon after New Year’s Day 1848. This lecture, too, went well. “I read a part of my excursion to Ktaadn to quite a large audience,” he reported to Emerson in England, “whom it interested. It contains many facts and some poetry.” The faithful Abigail and Bronson Alcott were again in the audience, and Bronson liked the lively description of wild “Kotarden”—a misspelling that suggests how the Penobscot word sounded from Thoreau’s mouth. Thoreau’s goal is suggested by a line from his Walden lectures: “I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life . . . to drive life into a corner, and if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it . . . or if it were sublime to know it by experience and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.”

Two months later, Thoreau had that true account ready. Hoping “Ktaadn” would bring in some much-needed dollars “to manure my roots,” he asked James Elliot Cabot—Louis Agassiz’s assistant, now working on the new Massachusetts Quarterly Review—whether they paid for contributions. In the Dial days, Thoreau let his work go for free, but when Cabot admitted they couldn’t pay, Thoreau sent “Ktaadn” to Greeley, who snapped it up with a check for 25 dollars: It was worth at least that much, he said, even though it was too long for the Tribune and “too fine for the million.” Once again Greeley hit the mark: two months later, in July 1848, the first of five monthly installments appeared in the Union Magazine. Thoreau’s next letter from Greeley included another check, for fifty dollars. “To think that while I have been sitting comparatively idle here, you have been so active in my behalf!” Thoreau wrote back in amazement. He added a paragraph telling Greeley about life at Walden: living simply, in a house he built himself, on a dollar a day earned by manual labor. Greeley, the sharp-eyed journalist, spotted a good story. He ran the paragraph under the title “A Lesson for Young Poets” in the New-York Daily Tribune on May 25, 1848. The piece went viral, reprinted in newspapers across the country. Suddenly Thoreau was hot. “Don’t scold,” pleaded Greeley. “It will do great good,” and only a handful of people would know who it was. To sweeten his apology, he enclosed yet another check, for 25—the balance for “Ktaadn.”

The way was open: Greeley knew exactly how to propel Thoreau to the top of the national marketplace. Write short pieces, he urged; follow out your thought, write an essay on “The Literary Life.” And for goodness sakes, advertise! Get up some short passages from the book manuscript and get them printed around. “You must write to the magazines in order to let the public know who and what you are. . . . You may write with an angel’s pen, yet your writings have no mercantile, money value till you are known and talked of as an author.”

Greeley’s cagey business sense, plus his frank opinion that Thoreau was a major author worth real money, gave Thoreau the confidence to sass Emerson when his old mentor wrote from England to ask Thoreau to help out, for free, yet another worthy but failing literary journal—that same Massachusetts Quarterly Review he had already rejected. Shortly before Emerson left for England, some of the old crew had gathered to talk about reviving the Dial. Theodore Parker took the lead, launching a new journal in December, but by May 1848, dire reports were reaching Emerson in England: The fledgling journal was faltering. Thoreau, he urged by mail, must “fly to the rescue.” But Thoreau wasn’t having any of it. The problem, he tartly wrote back, wasn’t getting “good things printed,” but getting them written. Who needed more “impassable swamps of ink & paper”? “How was it with the Mass. Quart. Rev.? . . . I read it, or what I could of it,” and if one man had written it, not one publisher would have printed it. “It should have been suppressed for nobody was starving for that.” As for himself? “Greeley has sent me $100 dollars and wants more manuscript.” So there. “Thank Henry for his letter,” Emerson wrote Lidian, his wife. “He is always absolutely right, and particularly perverse.” The instant Emerson was home from Europe, he withdrew his support from Parker’s magazine, which folded after three years. Thoreau never published in it.