In late 1884, after delivering an evening lecture at Chickering Hall, Samuel Clemens ventured out into the soggy New York City night. November had brought with it both cold and rain, leaving only a few brave souls on the dark streets.

Clemens had appeared as his alter ego, Mark Twain, the mustached writer and raconteur, who could enrapture a crowd as easily as a reader. The 48-year-old former newspaperman had become a household name with The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876), The Prince and the Pauper (1881), and Life on the Mississippi (1883). His new novel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, would debut in England and Canada in three weeks, and in the United States in February. Living off book royalties made for precarious finances, which is why Clemens worked the lecture circuit and dabbled in business.

As he walked home, two men emerged from a building ahead of him, continuing their conversation on the sidewalk. The cloudy night and weak glow of the gaslights made it difficult to figure out their identities, but Clemens could hear what they were saying.

“Do you know General Grant has actually determined to write his Memoirs and publish them? He said so, to-day, in so many words,” said one.

“That was all I heard,” wrote Clemens in his autobiography, “and I thought it great good luck that I was permitted to overhear them.”

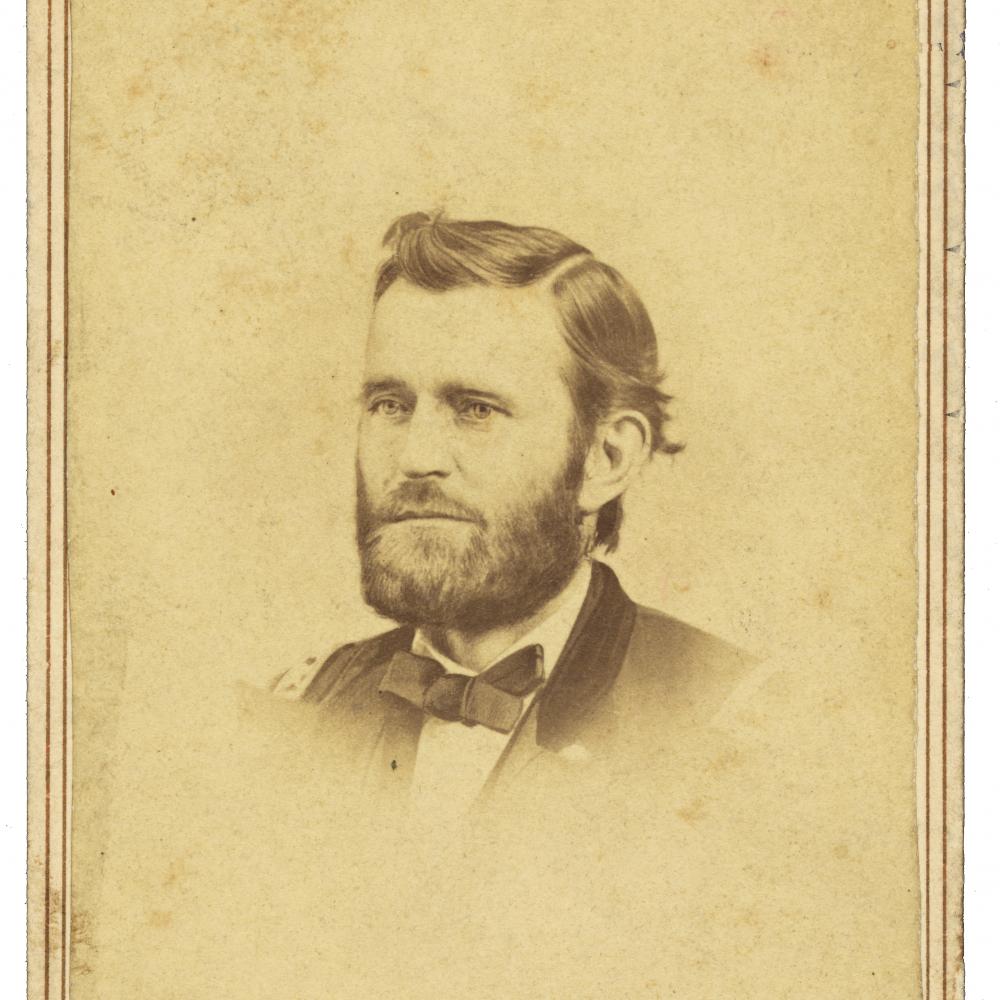

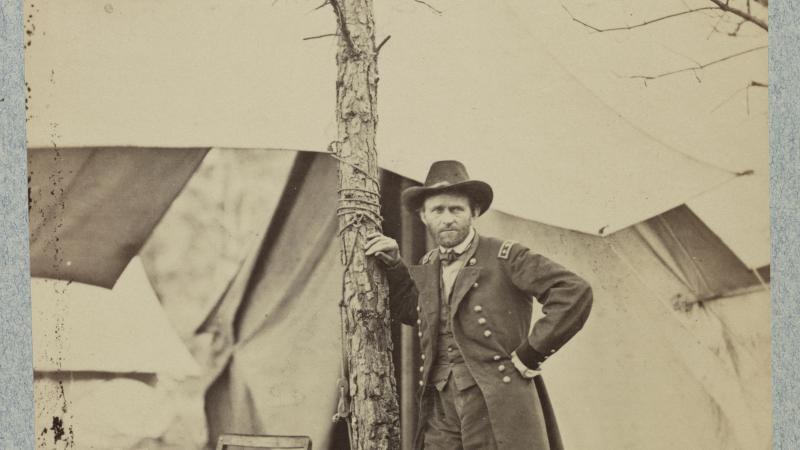

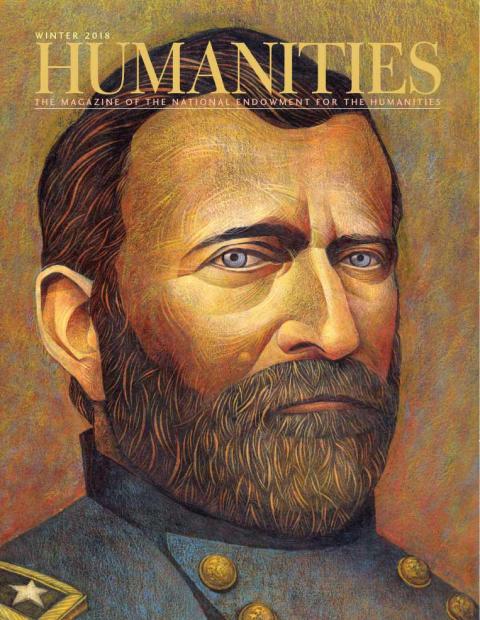

Ulysses S. Grant, Civil War hero and two-term president, had always declined offers to write his memoirs. Even when Clemens, his good friend and cigar-smoking buddy, broached the idea, Grant demurred. He didn’t need the money and “he was not a literary person.”

Clemens—and many others—thought it was a missed opportunity, given Grant’s colorful career and place in American history. The son of an Ohio tanner, Grant had scraped through West Point but fought with distinction in the Mexican-American War. In the 1850s, he traded soldiering for civilian life, resulting in some hardscrabble years with his wife, Julia, and their four children. When the Civil War erupted, he sided with the North and returned to uniform, rising from captain of a volunteer company to commanding general of the Union Army in four years. It was to Grant that General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Confederate Army at Appomattox in April 1865, ending the grisly four-year conflict. Grant’s status as a Civil War hero helped him win the presidency twice (1868 and 1872) during the rough-and-tumble Reconstruction years.

His life after leaving the White House had been happier than not. Still a spry man entering his late 50s, Grant indulged his wanderlust, embarking on a two-year around-the-world tour, before finally settling in New York City, where he and his wife, Julia, made a home in a roomy brownstone on East 66th Street a few blocks from Central Park. “We are all well,” he wrote his daughter, Nellie, at the end of November 1883. “Your brothers are all doing well and are happy. As a family we are much better off than ever we were before. The necessity for strict economy does not exist or is not so pressing as it has heretofore been.”

One month later, the spell broke. On Christmas Eve 1883, Grant slipped on a patch of ice in front of his house. The injury to his left leg and the rheumatism that followed rendered him infirm for months, dependent on crutches, and gripped by teeth-clenching pain.

Things only got worse as 1884 progressed. A Mexican railroad scheme that Grant had invested in failed. That was quickly followed by the implosion of Grant & Ward, the Wall Street investment firm started by his son Buck. After being impressed with the firm’s early returns, Grant invested his own money with the duo. Ferdinand Ward, Buck’s partner, turned out to be a huckster who excelled at manipulating loans and, by May 1884, the firm teetered on the edge of bankruptcy. To prop up the firm and his family’s good name, Grant borrowed $150,000 from William Vanderbilt. Even that didn’t help. As Grant & Ward collapsed, it swallowed the family fortune. The Grants were ruined.

As they mortgaged memorabilia and property to make payments on Vanderbilt’s loan, Grant continued to dismiss the idea of writing his memoirs, despite the money he might earn. “I do not feel equal to the task of collecting all the data necessary to write a book upon the War, or of my travels,” he wrote.

He decided, however, to take up an offer by Century Magazine to write an article about the Battle of Shiloh. While commander of the Union’s Army of the Tennessee, Grant countered a surprise attack launched by the Confederate Army of Mississippi in April 1862. The two-day battle left 23,000 men dead or wounded and offered a gruesome preview of the bloodletting to come. On the back of the $500 check Grant received for his efforts, he wrote, “First money ever paid to General Grant for the articles from his pen after his financial failure.”

The enthusiastic response to his article—it was a smash hit for the magazine—made Grant reconsider publishing his memoirs. Having discovered his inner “literary person,” he found he liked writing. The money would also begin to remedy his family’s financial predicament. The sixty-two-year-old Grant fretted about how Julia would live when he passed on, a worry that became more pressing after he learned he had throat cancer in October 1884. The treatments—gargling with a potash and yeast solution or coating the area with codeine, morphine, or cocaine—could ease the pain of the cancer consuming his right tonsil, but they would not cure it. Grant was a dead man walking.

The morning after overhearing the gossip about Grant and his memoirs, Clemens paid a call. The timing was auspicious, as Grant was about to sign a contract with Century, from which he would earn 10 percent royalties. Clemens was appalled. “I explained that these terms would never do; that they were all wrong, unfair, unjust, I said.”

Clemens wanted Grant to ask for a better deal, but Grant wasn’t so sure. He needed the cash, and the contract seemed fair as it stood. He also felt a certain amount of loyalty to Century for putting money in his pocket when he barely had two nickels to rub together. But Fred, Grant’s oldest son, found Clemens’s arguments persuasive and convinced his father to delay signing the contract.

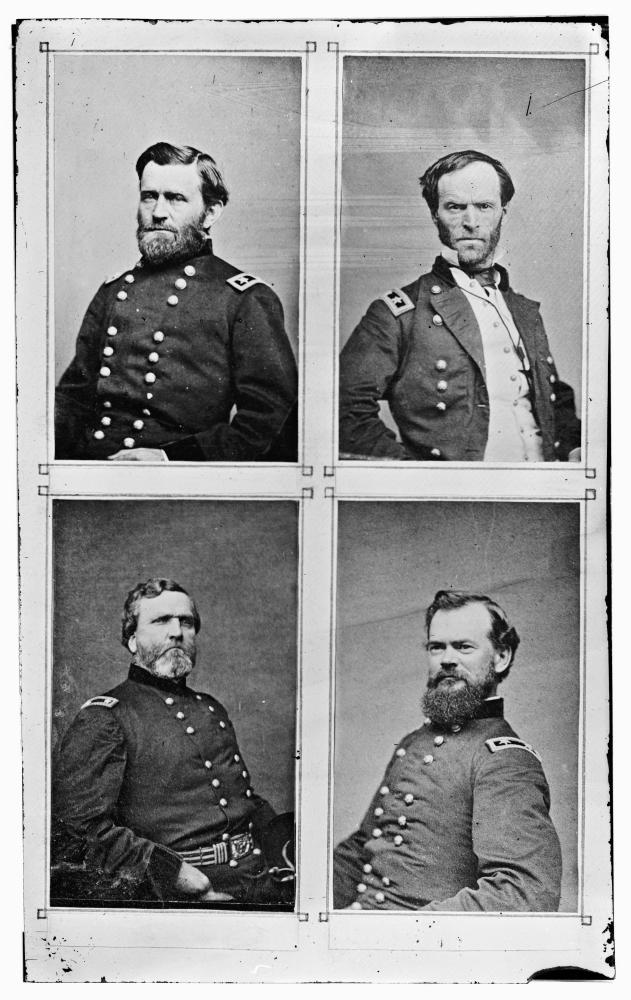

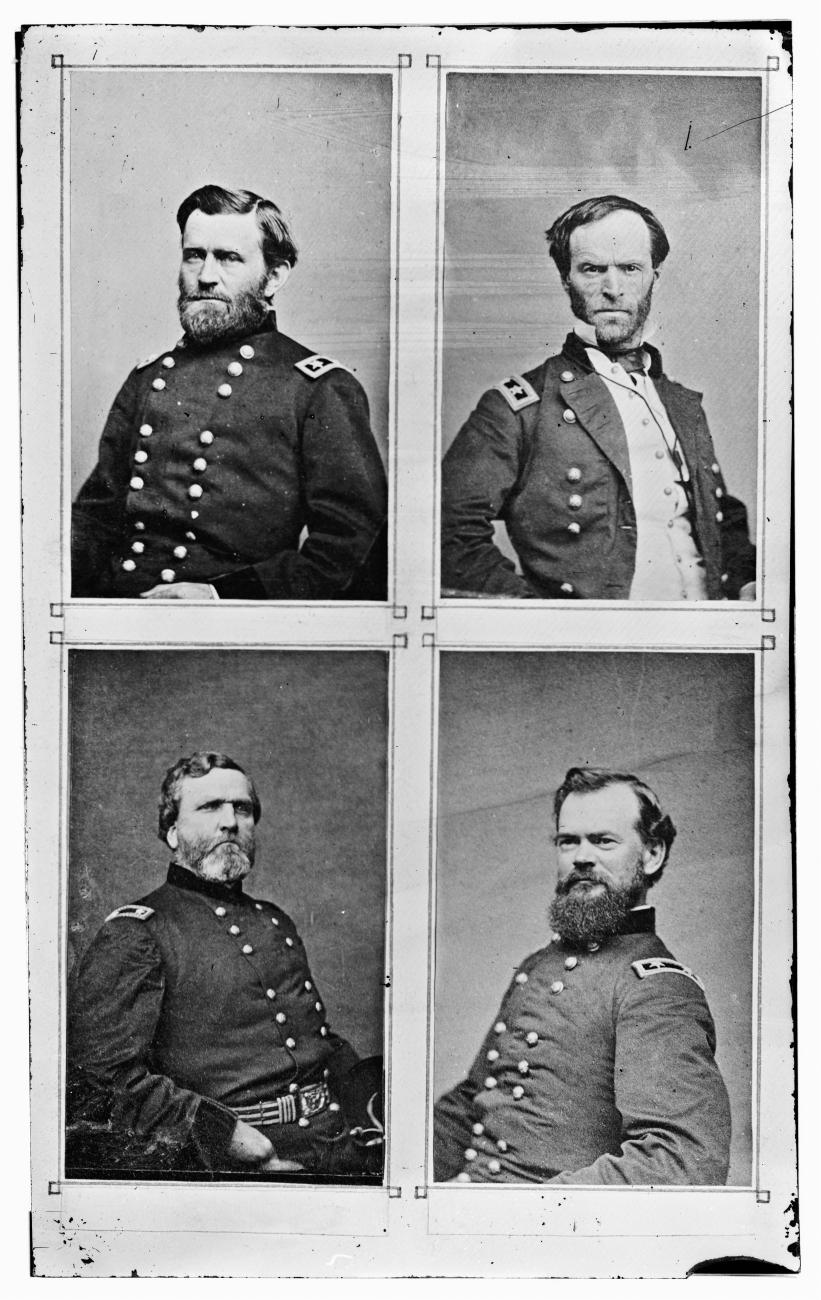

At a second meeting, Clemens again offered to publish Grant’s memoirs. This time money was clearly on Grant’s mind. “Sherman told me that his profits on that book were twenty-five thousand dollars,” said Grant. General William T. Sherman, known to his men as “Uncle Billy,” was one of the war’s most notorious figures, lauded and derided for his decision to burn Atlanta to the ground.

“Do you believe I could get as much out of my book?” asked Grant.

Clemens assured him he would.

But Grant wasn’t so sure. He had tried once before to sell his memoirs for $25,000, and the publisher ran away scared.

In response, Clemens offered to publish the book through his own publishing house and to write a check for $50,000 on the spot. Grant refused it on the grounds of their friendship. What if the book failed?

Clemens made a new offer: Grant could either have a 20 percent royalty or 75 percent of the profits. Clemens would pay for all expenses related to the printing of the book, from typesetting to binding. Grant laughed at the terms, questioning whether Clemens would make any money. Clemens was confident he would clear $100,000 in six months. Grant still didn’t believe him. Instead of being insulted, Clemens ascribed Grant’s disbelief to his being “a literary person.”

“He was aware, by authority of all the traditions, that literary persons are flighty, romantic, unpractical, and, in business matters, do not know enough to come in when it rains, or at any other time,” wrote Clemens. But when it came to publishing, Clemens knew his stuff. Bad experiences over the previous two decades left him cynical and skeptical of publishers and their motives. In his view, publishers sought to make money for themselves at the expense of the author. Determined that Grant should get the best deal possible, Clemens broke the taboo against talking about money. He detailed his earnings over his career and what Grant’s memoirs might make by comparison.

In February 1885, Grant agreed to give the book to Charles Webster & Company in a deal brokered by Clemens, who, angry at his own publishing house, had decided another firm should have it. The terms were favorable to Grant, and his heirs would receive 70 percent of any profits made on the book.

Even as Grant debated who should publish his memoirs, he plunged into the writing, working for five to seven hours a day in his library. The agony of his throat provided a constant reminder that time was not on his side. “It is nearly impossible for me to swallow enough to sustain life, and what I do swallow is attended with great pain,” he wrote his old friend General Edward Beale in mid December 1884. “It pains me even to talk. I have to see the doctor daily, and he does not encourage me to think that I will be well soon.”

Fred and Grant’s longtime military aide, Adam Badeau, helped check facts. Sons Buck and Jesse pitched in as well. So, too, did Harrison Terrell, the Grants’ African-American servant. Letters went out to old friends and men with whom he served, asking them to verify a story or how a series of events unfolded.

The memoir that emerged is not like memoirs of today. There’s little self-reflection or excavation of past emotional landscapes. Grant doesn’t explain why he issued General Order No. 11, which expelled Jewish merchants from Tennessee, Kentucky, and Mississippi in December 1862, making what Ron Chernow calls “the most egregious decision of his career.” He doesn’t delve into the damage he caused to himself and others by his drinking. Despite having a close relationship with Julia he refers to her sparingly. (Julia would later write her own memoirs.) He doesn’t explore the hard financial times he experienced in the 1850s, let alone the political differences that ran through his extended family. Julia’s family owned slaves, while Grant’s supported the abolitionists.

Instead of sharing the interior story of his life, Grant shares the exterior—the man out in the world trying to make his way through perilous times. He put readers in the saddle with him as he fought the Civil War, devoting the bulk of the 70-chapter book, chapters 17 to 67, to the conflict. It’s a story he could readily narrate and one in which he occupies the role of a humble hero.

“My family is American, and has been for generations, in all its branches, direct and collateral,” writes Grant at the start of Chapter 1. After offering his bona fides as an eighth-generation American, Grant quickly dispenses with his childhood and West Point tenure, and plunges into the Mexican-American War. Grant was disappointed at being made quartermaster until he realized that his position put him near the front lines, where he encountered plenty of action and several opportunities to distinguish himself. He rode full bore through a sniper-ridden town square, hanging off a horse to deliver a message. He risked his life to save that of F. T. Dent, his West Point classmate and future brother-in-law. And although he didn’t know it at the time, he was taking stock of the men he would fight with and against 15 years later.

As he recounts his time fighting in a conflict he came to despise for its role in fueling the Civil War, his sense of humor emerges. On acquiring a new horse: “I had, however, but little difficulty in breaking him, though for the first day there were frequent disagreements between us as to which way we should go, and sometimes whether we should go at all. At no time during the day could I choose exactly the part of the column I would march with.” On dealing with logistics: “I am not aware of ever having used a profane expletive in my life; but I would have the charity to excuse those who may have done so, if they were in charge of a train of Mexican pack mules at the time.”

He also takes stock of the lessons imparted by his superiors. “General [Zachary] Taylor never wore a uniform, but dressed himself entirely for comfort. He moved about the field in which he was operating to see through his own eyes the situation,” wrote Grant. Meanwhile, General Winfield Scott “always wore all the uniform prescribed or allowed by law when he inspected his lines. . . . On these occasions he wore his dress uniform, cocked hat, aiguillettes, sabre, and spurs.” While Grant’s disdain for pomp and epaulets is unmistakable, he saves his true condemnation for Scott’s burnishing of his reputation. “Orders were prepared with great care and evidently with the view that they should be a history of what followed,” wrote Grant.

During the Civil War, Grant would take his cue from Taylor, preferring the simple uniform of a private rather than the brass buttons and gold braid his rank commanded. He also admired Taylor’s ability to write an order “so plainly that there could be no mistaking it.” Grant’s clarity in drafting orders and reports made it hard for his subordinates or men in Washington to mistake his meaning. That same language is in evidence in his memoirs. The prose is muscular and spare, shorn of adverbs and the flights of fancy that marked so much Victorian prose.

After the Mexican-American War, Grant races through the 1850s, stopping only long enough to get married, start a family, and explain his various business ventures. These were lean and often difficult years for the Grants, which accounts for his cursory treatment. Before plunging into the Civil War, he offers a stirring defense of the Union and a condemnation of slavery, while skewering the Confederate cause. It is here, more than anywhere else in the book, that Grant seems to be writing for history and to make his stance clear. He argues there would have been no war if Southern leaders had not deployed inflammatory rhetoric in their push for more slave states. “They denounced the Northerners as cowards, poltroons, negro-worshippers; claimed that one Southern man was equal to five Northern men in battle; that if the South would stand up for its rights the North would back down,” he wrote. “Secession was illogical as well as impracticable; it was revolution.”

As he leads the reader through the war and his rise up the ranks with each new victory, Grant acts as tour guide and tactician. He explains the lay of the land, the challenges his troops faced, and the fighting as it unfolds. To keep the “and then, and then” pace from growing wearisome, especially as the regiments, colonels, and generals pile up, Grant wisely inserts pauses to help the reader catch their breath.

During his first outing of the Civil War, he describes the uneasy feeling of finding every house deserted along a 25-mile stretch of road. As he approached the camp where the Confederates waited, his fear rose. “My heart kept getting higher and higher until it felt to me as though it was in my throat. I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to halt and consider what to do; I kept right on.”

Grant offers another such moment in the runup to Shiloh, when his horse slipped in the mud and fell, landing on top of Grant’s leg. When his ankle swelled to dangerous proportions, his boot had to be cut off. A few days later, restless in the middle of the night from the throbbing pain and the rain which “fell in torrents,” he sought shelter in a log house. “This had been taken as a hospital, and all night wounded men were being brought in, their wounds dressed, a leg or an arm amputated as the case might require, and everything being done to save life or alleviate suffering,” he wrote. “The sight was more unendurable than encountering the enemy’s fire, and I returned to my tree in the rain.”

The narrative turns novelistic in its character sketches as Grant describes the men with whom he fought beside and against, capturing their personalities and quirks with a sure hand. “[Braxton] Bragg was a remarkably intelligent and well-informed man, professionally and otherwise,” wrote Grant. “He was also thoroughly upright. But he was possessed of an irascible temper, and was naturally disputatious.” Grant saw James Longstreet as Bragg’s flip side. “He was brave, honest, intelligent, and a very capable soldier, subordinate to his superiors, just and kind to his subordinates, but jealous of his own rights, which he had the courage to maintain.” George Meade was “an officer of great merit, with drawbacks to his usefulness beyond his control,” namely his temper and a tendency to “speak to officers of high rank in the most offensive manner.” Ambrose Burnside wasn’t fit to command an army and “no one knew this better than himself.”

Grant makes no secret of his admiration of Abraham Lincoln. “Mr. Lincoln gained influence over men by making them feel that it was a pleasure to serve him.” The two men didn’t meet face to face until a White House ceremony in March 1864, during which Grant received his promotion to lieutenant-general. Knowing Grant’s dislike of public speaking, Lincoln shared with him the short speech he would be giving, so Grant could prepare something in advance. The gratitude for the gesture springs from the page. Grant, however, had a decidedly different view of Edwin Stanton, the secretary of war. “Mr. Stanton never questioned his own authority to command, unless resisted. He cared nothing for the feeling of others. In fact it seemed to be pleasanter to him to disappoint than to gratify.”

After leading his readers through the battlefields of Missouri, Tennessee, and Mississippi, Grant delivers them to Virginia and the final showdown with Robert E. Lee. Since the beginning of the war, Lee had occupied a towering place in the imaginations of both the North and South as a man who could not be defeated. Even as Grant’s successes mounted, his staff frequently heard, “Well, Grant has never met Bobby Lee yet.” Grant, however, had met Lee during the Mexican-American War. “I had known him personally, and knew that he was mortal; and it was just as well that I felt this,” he wrote.

When Lee’s army finally crumbled under Grant’s assault, he had no choice but to ask for terms in April 1865. Knowing his readers would want the inside story on Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Grant carefully unspools the tale, interspersing reprints of their exchange of letters with personal details.

The meeting between the two men had been arranged so quickly that Grant arrived in his field uniform, reeking of mustard, a common treatment to battle the headache that had bedeviled him for days. “In my rough traveling suit, the uniform of a private with the straps of a lieutenant-general, I must have contrasted very strangely with a man so handsomely dressed, six feet high and of faultless form.” Lee wore an immaculate uniform and a ceremonial sword for the occasion. The meeting began on an amiable note, with some chitchat about whether they had met during the Mexican-American War. Lee thought they had met, but Grant doubted he would have taken notice of an officer 16 years his junior.

“What General Lee’s feelings were I do not know,” Grant wrote of the moment of Lee’s surrender. “As he was a man of much dignity, with an impassible face, it was impossible to say whether he felt inwardly glad that the end had finally come, or felt sad over the result.” Grant, however, acknowledged the occasion left him “sad and depressed.” “I felt anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

In mid June 1885, the Grants packed up and headed north to Mount McGregor in New York’s Adirondacks. Banker Joseph Drexel offered the Grants the use of his summer cottage, allowing them to escape the sweltering weather that descended on Manhattan in the summer. Grant continued work on his memoirs even as his body rejected food and coughing fits left him gasping for air. Speaking became impossible, forcing him to scribble notes with a pencil.

In late June, he finished writing his memoirs. “There is much more that I could do if I was a well man. I do not write quite as clearly as I could if well,” he wrote Clemens. In less than a year, Grant made it from his childhood through the Civil War and Lincoln’s assassination. Left unwritten were his eight years in the White House and around-the-world tour, a particularly joyful period of his life. But he had no strength left for that.

On July 20, he finished reviewing the text of his memoirs. Three days later, on July 23, he was dead.

The resulting book, The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, ran 336,000 words, requiring publication as two volumes. A clothbound version sold for $7, while the leather version cost $25. To drum up sales, his publisher sent out an army of 10,000 door-to-door salesmen equipped with a 37-page guide on how to talk about Grant and close a sale. They sold 300,000 copies, turning the books into a publishing phenomenon. The first check Julia Grant received was for $200,000, then the largest royalty check ever paid out. In the end, the book would provide her with more than $420,000 ($11 million in today’s money). True to Clemens’s prediction, the publisher made more than $200,000.

Personal Memoirs were also praised as literature. Clemens compared them to Caesar’s Commentaries in “clarity of statement, directness, simplicity, unpretentiousness, manifest truthfulness, fairness and justice toward friend and foe alike, soldierly candor and frankness and soldierly avoidance of flowery speech.” William Dean Howells noted that Grant’s memoirs were “written as simply and straightforwardly as his battles were fought, couched in the most unpretentious style.”

British critic Matthew Arnold also praised Grant’s memoirs while taking a few shots at him. When they met in London in 1877, Arnold had not taken to Grant, finding him “ordinary-looking, dull and silent.” Reading his memoirs changed Arnold’s mind. “An expression of gentleness and even sweetness in the eyes, which the portraits in the Memoirs show, escaped me,” wrote Arnold. Yet even as he lauded the former president, Arnold couldn’t help but mock his grammar, calling it “an English without charm and without high-breeding.”

Arnold’s remarks prompted Clemens to mount a voracious defense of Grant. “When we think of General Grant our pulses quicken and his grammar vanishes,” he said in an 1887 speech. “We only remember that this is the simple soldier, who, all untaught of the silken phrase makers, linked words together with an art surpassing the art of the schools, and put into them a something which will still bring to American ears, as long as America shall last, the roll of his vanished drums and the tread of the marching hosts.”

Grant’s memoirs continued to stay in print throughout the twentieth century and gain new fans, including Sherwood Anderson, Gertrude Stein, and Sinclair Lewis. They all considered writing a book about him. The general’s popularity has continued into the current century with hefty biographies by H. W. Brands, Ronald C. White, and Ron Chernow appearing in the past five years alone.

And last fall saw a new edition of the memoirs edited by John F. Marszalek, David S. Nolen, and Louie P. Gallo, editors of The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, published by Harvard University Press. Grant was writing at a time when the men and places relating to the war remained fresh in the minds of the American public. More than 150 years later, twenty-first-century readers need a helping hand. The editors use the footnotes to offer biographical details, give geography lessons, and provide more information about a historical moment. The mini stories contained in the annotations bolster the complexity of the story unfolding above. The extensive sourcing, drawn from the Grant papers project, also provides a springboard for interested readers and scholars to explore further.

“With these remarks, I present these volumes to the public, asking no favor but hoping they will meet the approval of the reader,” writes Grant at the end of the preface. Instead of parades and elaborate commemorations of the war, Grant wanted Americans to have a “truthful history” of the conflict. With Personal Memoirs, he spoke his version of the truth, one that is still worth reading.