I keep thinking of what it must have taken to escape, and to a place like this no less. Who would have had the courage? A slave on the run—let’s call him Elijah—might have heard barking and other sounds of hounds chasing him. Running low and hunched over, Elijah would have made his way through fields of wheat, their tawny stalks swaying in the slight nighttime breeze. The heat of the Tidewater region could be stifling, but the chance to run didn’t come every day. Maybe his master had left the plantation to join the Continental Army, leaving fewer men to supervise. Elijah would have grown up hearing whispered rumors of a nearby refuge for escapees in the sprawling swamp that lay near his master’s fields. Men like Elijah, hundreds of them, had worked to dig canals into the peaty soil to drain the wetlands and expand the workable farmland. More than a few slaves probably thought about seeking their own liberty. But it must have taken a certain kind of courage to leave, and to seek freedom in the Great Dismal Swamp.

Located in southeastern Virginia, the lone surviving remnant of a sprawling wetlands that formerly stretched over one million acres of coastal plain, the Great Dismal Swamp is now largely confined to 112,000 acres of wildlife refuge. Though modified by centuries of human encroachment, it remains one of the largest intact wild areas left on the Atlantic Coast. From a Native American legacy reaching back at least 6,000 years to a motley assemblage of criminal fugitives, moonshiners, poachers, and outlaws that flourished until relatively recently, the swamp has seen its share of vibrant American history. Perhaps most fascinating, however, is the story of the Maroons, a hybrid band of fugitive slaves and isolated Native Americans that held out deep in the inaccessible interior from the 1600s until after the Civil War. Today, the story of the Maroons is finally coming to light through groundbreaking archaeological work.

Beginning in the early seventeenth century, the swamp was slowly surrounded by English agricultural plots worked by slaves. Its unapproachable interior was a powerful attraction for slaves desperate to escape servitude. Arriving with little more than their clothing, some runaways established a relationship with the Native American peoples, a loose collection of several Algonquian tribes who had been hemmed in by colonial development and separated from other Indians. From the Indians, escaped slaves learned subsistence techniques of hunting, fishing, and cultivation of the scattered hummocks that still rise in places above the black waters.

Tools were scarce. The thick peat foundation of the swamp provided few stone outcrops for the fashioning of essential knives, axes, or arrowheads. Maroons sometimes resorted to digging up and refashioning discarded stone implements brought into the swamp during millennia past. Dan Sayers of American University, an archaeologist who pioneered the first systematic excavations of the Great Dismal Swamp’s human past, is one of the country’s leading authorities on this long-lived subculture. His team’s groundbreaking surveys, involving less than 1 percent of the swamp, have uncovered cabin foundations, fire pits, middens, and heavily used and reused stone implements, what he calls “resuscitated” tools, made of chert, quartzite, and flint—a careful reuse of ancient stone implements not previously known to science.

In the Great Dismal Swamp’s Maroon people we have an essentially Stone Age culture existing in absolute self-reliance and isolation on the heavily populated East Coast until the mid nineteenth century. At that point, lumber interests built extensive canals into the swamp to access the old-growth cypress and white cedar of the interior, introducing trade, conflict, disease, and resulting in the dissolution of Maroon culture.

The nearest historic drainage canal—which had originally been commissioned by a young George Washington—is a mere three miles from where archaeologists have been digging. They have been working in a strata corresponding with the 1850s, where the first iron tools were found. Their appearance coincides with the demise of the Maroon culture and the final abandonment of the swamp after which very little is known about these people.

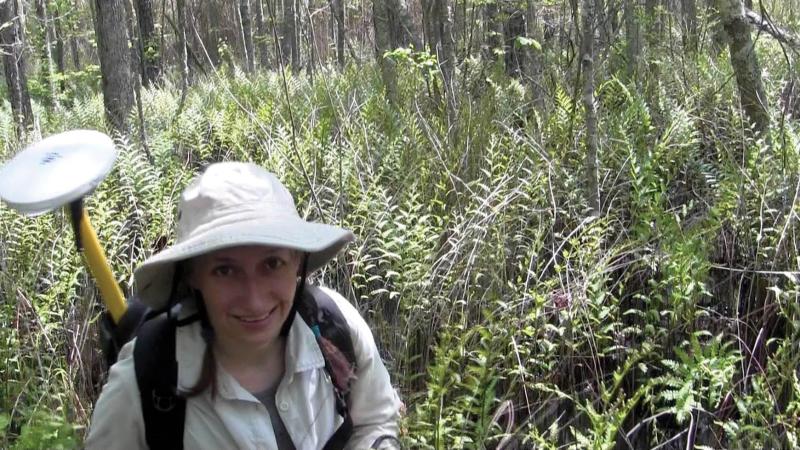

Becca Peixotto is a doctoral student in archaeology at American University who was introduced to the Maroons’ legacy by Sayers and now independently works the digs with her own team of students. On a visit to the swamp last September, I accompanied Peixotto on one of her excavations. After driving a few miles along a rutted dirt road, through dense stands of beech, ash, holly, and pine interlaced with formidable thickets of greenbrier, we pulled over to the side and got out. We pulled chaps over our long pants (for briars) and rolled down our long sleeves (for bugs). Carrying the tools of her trade in a small backpack, Peixotto led the way into the woods, following a dim trail with the help of bright ribbons tied to branches. On the way we passed a massive hardwood tree that had fallen, with its intact rootball looming over a wide shallow basin filled with rainwater. This imposing sight was, Peixotto told me, an excellent source of artifacts, as the uprooted tree had essentially done the work for them and exposed several layers of topsoil.

This was my first experience at an archaeological dig, and being an avid student of Greco-Roman, Egyptian, and Mesoamerican history, I was a bit disappointed when we finally arrived, swatting mosquitoes, gnats, and biting flies, at a small, precisely edged T-shaped quarry only about six inches in depth. Despite the shovels, logs, and other weights holding them in place, curious bears had scattered the tarps that Peixotto’s team had placed over the dig to protect it from the region’s habitually torrential rain. Like the Everglades, the Great Dismal Swamp is a non-riverine wetland, wholly dependent on rainfall to nurture its pocosin—that is, swampy—ecosystem. I wasn’t expecting a pyramid, but this shallow pit wasn’t too impressive to my untrained eye. And the artifacts themselves, which were displayed to me in carefully labeled plastic bags, weren’t terribly dramatic either—just tiny shards of muddy stone.

I helped Peixotto arrange some of her tools and then, sitting at the edge of the dig and taking notes with one hand while swatting insects with the other, I asked her if this particular project held as much interest for her as, say, an excavation in Mesopotamia. “Yes!” she exclaimed. “Every archaeologist gets asked if they’ve found gold, but for many of us, the value comes not from a single object or find but from the whole collection of artifacts and the context of the finds. In a place like the Dismal,” she continued, “where we find so few durable artifacts, as opposed to artifacts made of organic materials, which would decompose, such as baskets, each new artifact carries extra weight. My colleagues can attest to the excitement of encountering a small piece of glass and the flurry of photographs and careful documentation such a find unleashes.”

Peixotto, a petite woman with an intense gaze and quiet demeanor, was wearing a striped kerchief over her long hair. As I sat and watched her work, we discussed her personal and professional motivations for being here, at this place, mucking around in a wetland wilderness. “I’ve always had an interest in history,” she said, “and when I was young, we had a ‘museum’ shelf in the garage for things that surfaced in my grandparents’ barnyard. They lived on an old Vermont farm, and it was fun to find things left by the people who had lived there before. But it never occurred to me that I could be an archaeologist.”

But an archaeologist she became, helping to score what National Geographic called “one of the greatest fossil discoveries of the past half century.” This involved finding a new species of hominin, Homo naledi, in the Rising Star cave system some 30 miles northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa, in 2013. Parts of the cave’s tunnel were less than ten inches high, so the expedition leader, American paleoanthropologist Lee Berger, had to be very specific in his call for diggers. Skinny individuals wanted, he said on Facebook, with scientific credentials and caving experience who “must be willing to work in cramped quarters.” Peixotto and two colleagues, working in lengthy shifts with another three-woman crew, discovered and collected more than 400 fossils from the floor of the cave. Then they started digging around the half-buried skull that recreational cavers had found just a few weeks previously and which had initiated the excavation.

Within three weeks the six women had removed some 1,200 bones, which, according to National Geographic, was “more than from any other human ancestor site in Africa.”

Now Peixotto is placing her devotion to scientific storytelling in the service of an almost forgotten hybrid culture that existed in isolation until the mid nineteenth century. Using a trowel and a 1/16th-inch meshed screen, she sifts handful after handful of moist peat, ardently searching for the tiniest fragments of stone, any of which would likely have been imported into the swamp by ancient Americans, then reworked by their Maroon descendants. “Oh, here’s something,” Peixotto says, displaying a minute flake of edged stone no bigger than a fingernail. She handed it to me, and as I studied its muddy texture I began to appreciate the enormous challenges that surviving here must have posed. Imagine being so isolated that you had to rely on the leftover stone tools and weapons of a long-departed civilization. I could see in the Maroons what we people outside the swamp call the American spirit: fierce determination, resolute pragmatism, and an undying will to survive, to never surrender, under any conditions.

“This is such a compelling story, but it’s one that isn’t widely known,” Peixotto comments. “Here are people who lived in an unimaginably brutal system of enslavement who chose to go into the swamp and create lives for themselves ‘off the grid.’ There is so much we can learn about them and from them.”

The precursor to coal, peat is a spongy composite of decaying vegetation that forms the basis of the Great Dismal Swamp’s ecosystem. It is naturally acidic. Colonial-era mariners barreled the swamp’s opaque water and hauled it onboard their ships because it wouldn’t sour on transatlantic voyages. Peat is exceedingly efficient at trapping carbon and storing groundwater: Only 3 percent of the world’s surface, peat manages to trap twice the carbon as Earth’s entire forested biomass. But working with peat presents several challenges. As Peixotto places clump after clump of the black, sticky soil on her screen for sieving, her hands and nails become caked.

“We use these very fine screens to capture even the tiniest artifacts,” she says, “but the soil is often rather wet. Some days, it’s like pushing thick mud through a window screen and it can be very frustrating. It’s worth it, though, when we find tiny flakes of glass or flint or other materials. These things help us see what material culture the Maroons had at their disposal and how every object was reused, resharpened, and repurposed until nothing was left. They help us understand a little better what life might have been like for them.”

But what is it about the Maroons, I ask, that particularly attracts her time and effort? “For me, the essential mission of an archaeologist is to expose parts of history that have been suppressed, lost, forgotten, ignored, or misunderstood,” she says. “The lives of the vast majority of people are not recorded in history [but] archaeology can help us gain a fuller picture of the past so we can understand how we got where we are now and where we might go in the future.”

I agreed, at least in principle, but had to wonder how much we can learn about the Maroons from minuscule flakes of stone or, higher up in the stratigraphic layers, glass or metal. It’s fascinating to speculate about the lives of men and women who escaped slavery and built a new and strange life here in the swamp, but, I ask Peixotto, can the story of a vanished people ever be told in detail with such a paucity of physical evidence?

“We will probably never know what Maroons thought or felt about life in the swamp, what made them laugh or cry, apart from clues we can get from the few firsthand accounts we have,” she said. “With more exploration, excavation, and new technologies, we may eventually understand the extent to which the many Maroon communities in the swamp were connected with each other across the vast landscape. Eventually, we are also likely to find sites where organic artifacts like baskets or wooden bowls might be preserved. Finds like that would open a whole new window onto Maroon life.”

The humidity had become stifling, and bugs were hanging over our heads in clouds, so when Peixotto said that we were done for the day I was happy to help this remarkably resolute woman pack up her tools. We also secured the site as best we could against the refuge’s ursine inhabitants, whose strong sense of smell had doubtless already alerted them to our presence.

Amid brooding stretches of silent, black water, colonnades of massive cypresses looming stonily above the mire, and an obsolescent web of canals serving as a silent reminder of the limits of human endeavor, enthusiastic college students led by Peixotto and her mentor, Dan Sayers, are unveiling, piece by piece, one of the most obscure mysteries of American history. As we trudge back to the road, I contemplate the commitment of people like these, depending exclusively on objective data and thorough-going scientific analysis to tell the tale of a fascinating but lost piece of our history. But there is something more important about Peixotto’s dedication, and that of the conservation biologists, ecologists, and other scientists I’ve been privileged to interview over the years. It speaks to a deeper engagement than simply the collection of physical evidence and the publishing of scientific papers, something almost like an ethical commitment. I say as much to Peixotto.

“There’s an adage in anthropology and archaeology about giving voice to the voiceless,” she says as we happily remove our chaps beside her truck.

“The Maroons were marginalized and silenced in so many ways during their lifetimes, as enslaved people, as fugitives, as people living in marginal spaces like this. They continue to be marginalized in the stories we tell ourselves about our country, about the contributions of African Americans to our shared past, about the hardships of enslavement and the myriad ways Africans and African Americans resisted enslavement. I’ve met people who grew up and live near the Dismal Swamp who never learned about this history in school. That is a tragedy, and if I can put up with a few bugs and pesky bears and use my skills as an archaeologist to help bring Maroon voices out of the margins, then, yes, this work is as much a moral duty as a scientific one.”