One of the most celebrated and widely viewed paintings of the nineteenth century almost didn’t survive into the twentieth. The Battle of Gettysburg, a vast canvas with a vast audience—hundreds of thousands had once flocked to see it—was found by a Boston Globe reporter in 1904, moldering in a lean-to shed at the back of a vacant lot. It had been rolled up, bagged in oilcloth, and stuffed in rough wooden crates.

“The long box has been on fire two or three times in the years it has lain in the lot,” the Globe reported, with the flames doused not only by water, but by mysterious retardants from the fire department’s “chemical engine.”

“All this,” the reporter deadpanned, “probably has not helped to preserve the big painting in good condition.”

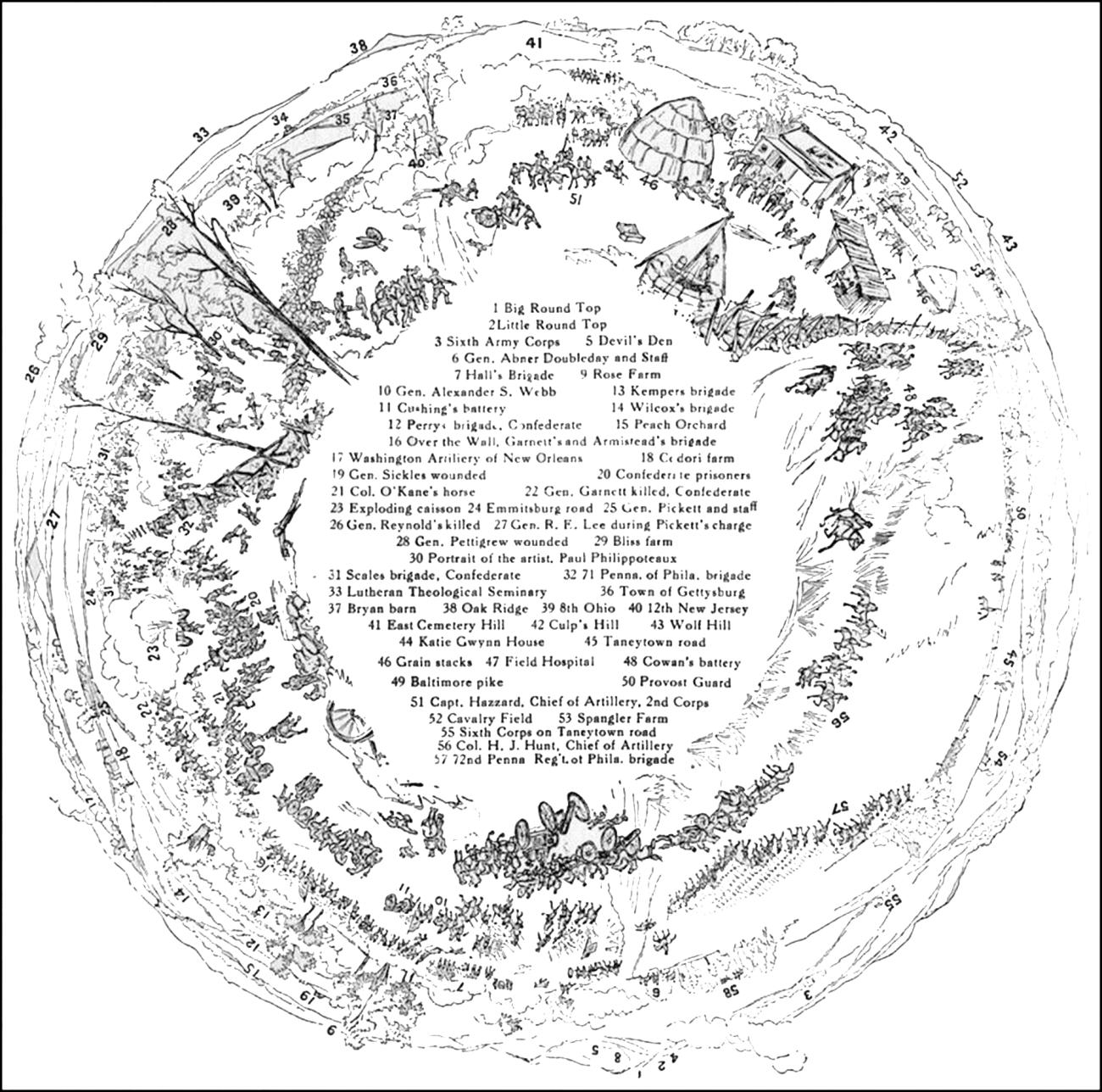

How big a painting? Forty-two feet from top to bottom, the canvas is 377 feet around. The Battle of Gettysburg was one of the great 360-degree paintings popular in the nineteenth century known as “panoramas” in Europe and “cycloramas” in the United States. Placing the viewer near the center of the action, the Gettysburg Cyclorama captures the moment, on July 3, 1863, when Confederate General George Pickett’s men charged into the Union lines on Cemetery Ridge.

The Battle of Gettysburg was painted in 1882–83 by a team of artists led by French painter Paul Philippoteaux. He had learned the craft from his father, Félix-Emmanuel-Henri Philippoteaux, one of the most prominent panorama painters of the mid nineteenth century. When it first went on display in Chicago in October of 1883, The Battle of Gettysburg proved so popular that Philippoteaux and his team were hired to produce three copies. There was so much demand for the painting that counterfeiters knocked off a dozen or more phonies, some slapdash, some (those produced by former assistants to the original artist) of high quality.

The copy of the painting made by Philippoteaux for display in Boston was eventually rescued from the vacant lot where it had been left to rot. The canvas was brought to Gettysburg in 1913 to be displayed as a tourist attraction; there it suffered further decay and repairs of clumsy expedience. Acquired by the National Park Service in the 1940s, The Battle of Gettysburg was finally given a thoughtful and deft restoration and went back on display in a new building in 2008.

The first panoramas were devised by English portrait-painter Robert Barker, who in 1787 took out a patent on the idea of a painting-in-the-round. He specified in the patent details of presentation—in particular the raised, central viewing platform—that would be used for most panoramas to come. The word “panorama” was coined to advertise the landscapes-in-the-round Barker put on display in Leicester Square, London. By the early 1800s panoramas could be seen across Europe, with canvases representing not only landscapes, but historic moments—great battles, in particular.

Were panoramas art or entertainment? Both. The giant paintings, exhibited in large, custom-built rotundas, required the investment of rich speculators, especially those with a knack for promotion. (In the 1870s P. T. Barnum was among those trying their hands at the cyclorama game.) But, from the beginning, Barker was at pains to argue that his innovation should “not be understood as an Exhibition merely for emolument,” but was “intended chiefly for the criticism of artists, and admirers of painting in general.”

When not driven by shameless commerce, propaganda purposes have often come into play: Napoleon wanted panoramas of all his great battles painted and displayed in Paris. In the 1980s the Egyptian army commissioned a panorama of the Arab-Israeli War.

Yet for all the commercial and political imperatives, the best panoramas are remarkable works of art—astonishing and affecting, complicated and compelling images liberated from the constraint of frames. The Battle of Gettysburg features as much pathos as ballyhoo. In one direction there are Union batteries largely obscured in smoke; opposite are caissons careening toward the front lines. Viewers are drawn to the first waves of Pickett’s charge met in melee at the stone wall; when one turns and faces the Round Tops, an improvised barnyard hospital comes into sight, the surgeons at work with their bone saws. The painting presents a romantic vision of heroism under fire, but it doesn’t lie about the carnage. Though not as gruesome as it could have been—say, if the painters had rendered the crimson mist when men were vaporized by canister shot—the dead and dying are everywhere, each rendered with heartbreaking individuality.

Panoramas demanded innovative technique. Among the challenges of painting in the round was mastering the peculiarities of cylindrical perspective—or as art historian Scott Wilcox has put it, “the difficulties of presenting straight lines on a curved canvas.”

There were other practical challenges. The great canvases were far too large to be completed (at least in a timely fashion) by any one painter: Panoramas were, of necessity, collaborative efforts executed by teams of artists. That teamwork required specialization, says Sue Boardman, who has coauthored histories of the Gettysburg cyclorama, and worked on the painting’s restoration. If different artists painted separate sections, she says, the whole would never hold together. Instead, each artist worked at his specialty. Take, for example, any one of the horseback figures in The Battle of Gettysburg: It’s likely that one artist painted the ground under the horse’s hooves, another the sky above; another painted the horse, another the body of the rider, and yet another painted the rider’s face.

From the beginning, a high value was placed on verisimilitude in panoramas, a you-are-there immediacy. That meant not only representational realism, but accuracy in the details of time, place, and events—even clothing. “As truthfulness of costume is one of the great necessities,” Philippoteaux told the New York Times early in his work on the painting, “I hope to get everything relating to the dress of the soldiery, with the traits of the brave combatants on both sides.”

Just as sticklers today scour period films for historical bloopers, so too the Cyclorama-goers of the nineteenth century found details to complain about. Philippoteaux painted Confederate General Lewis Armistead being shot from his horse; Armistead, critics quickly pointed out, was shot while leading his brigade on foot. And for all the artists’ efforts to achieve “truthfulness of costume,” the uniforms in the first version of the painting struck many viewers as “too French.”

The hyperrealism of panoramic painting enjoyed its 1880s heyday just as other artists were pushing the boundaries of abstraction. Monet’s Impression, Sunrise was among the proto-Impressionist paintings exhibited in Paris in 1874; Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold—The Falling Rocket was displayed (and provoked no little fuss) in 1877.

Dutch artist Hendrik Willem Mesdag painted a panoramic land- and seascape of the beach at Scheveningen (a painting still on display in the Hague). After seeing it in the summer of 1881, Vincent van Gogh repeated a jibe once made of Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson—that the “picture’s only fault is that it has no fault.” (This, even though Mesdag, of all the panorama painters of the time, may have been the least tethered to realism.)

And yet, to achieve realism Philippoteaux used some of the same techniques that were crucial to Impressionism. Bodies in the Gettysburg cyclorama that look quite detailed and specific at a distance are, up close, created with ambiguous brush strokes, and small streaks and blocks of contrasting colors. But unlike regular canvases, which can be approached—and are often viewed from altogether too close—the rotundas custom-built for panoramas purposely keep the audience at a specific distance, allowing the artists to paint with the exact level of imprecision calculated to look lifelike from the central viewing platform.

The realist imperative can veer into kitsch, though, with the faux terrain, an early French addition to panoramic presentation, which fills the space between platform and canvas with a diorama of real objects meant to extend the painting three-dimensionally. I find the theatrical staging of combat detritus in the foreground detracts from The Battle of Gettysburg, rather than adding to the effect.

The farthest point north that the Southern army reached at Gettysburg is often referred to as the “high-water mark of the Confederacy.” The Battle of Gettysburg can be thought of as the high-water mark of panoramic painting. From 1883 well into the 1890s, crowds thronged to see versions of Philippoteaux’s masterpiece in Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, and later in traveling shows around the country.

But the sad state of the Boston canvas in 1904 was emblematic of what had become of the cyclorama craze—it had been abandoned for a newer, more compelling visual entertainment: motion pictures. “Poor panorama, the joy of our grandparents,” Max Brod lamented in 1913, “today it is the cinema that makes our nerves tingle.”

Too big and expensive to store, the old cycloramas were dumped in vacant lots, or they rotted away in forgotten warehouses, or were ruined by rain or fire, or, in at least one case, cut up to make tents. Of the hundreds of panoramas produced in the nineteenth century, few survive, and fewer still are on display. (PanoramaCouncil.org maintains a list of the 360-degree paintings that can be seen worldwide.)

That makes The Battle of Gettysburg not just a remarkable feat of collaborative painting, but a rare relic of an artistic movement now largely forgotten, a work that is as much artifact as art.