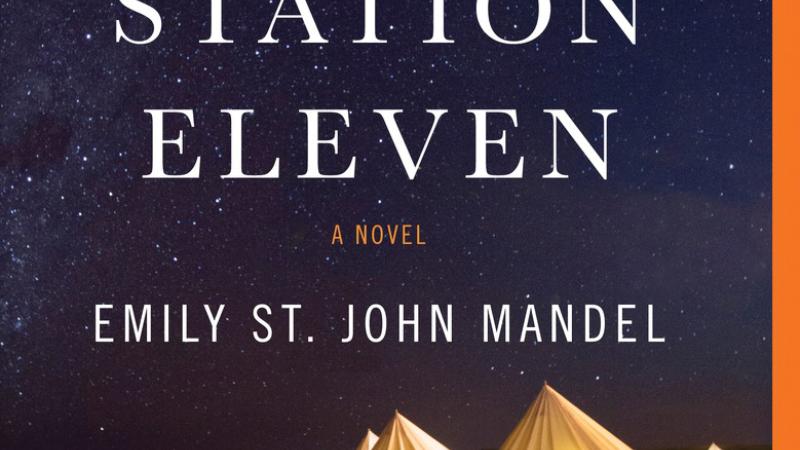

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel is the winner of the 2015 Arthur C. Clarke Award and was a finalist for the 2014 National Book Award. The book was chosen for the Great Michigan Read, a statewide discussion project in 300 communities sponsored by the Michigan Humanities Council. As the novel captures the journey of an itinerant Shakespearean troupe through the Great Lakes region, so here Mandel gives a glimpse of her own life on tour.

1.

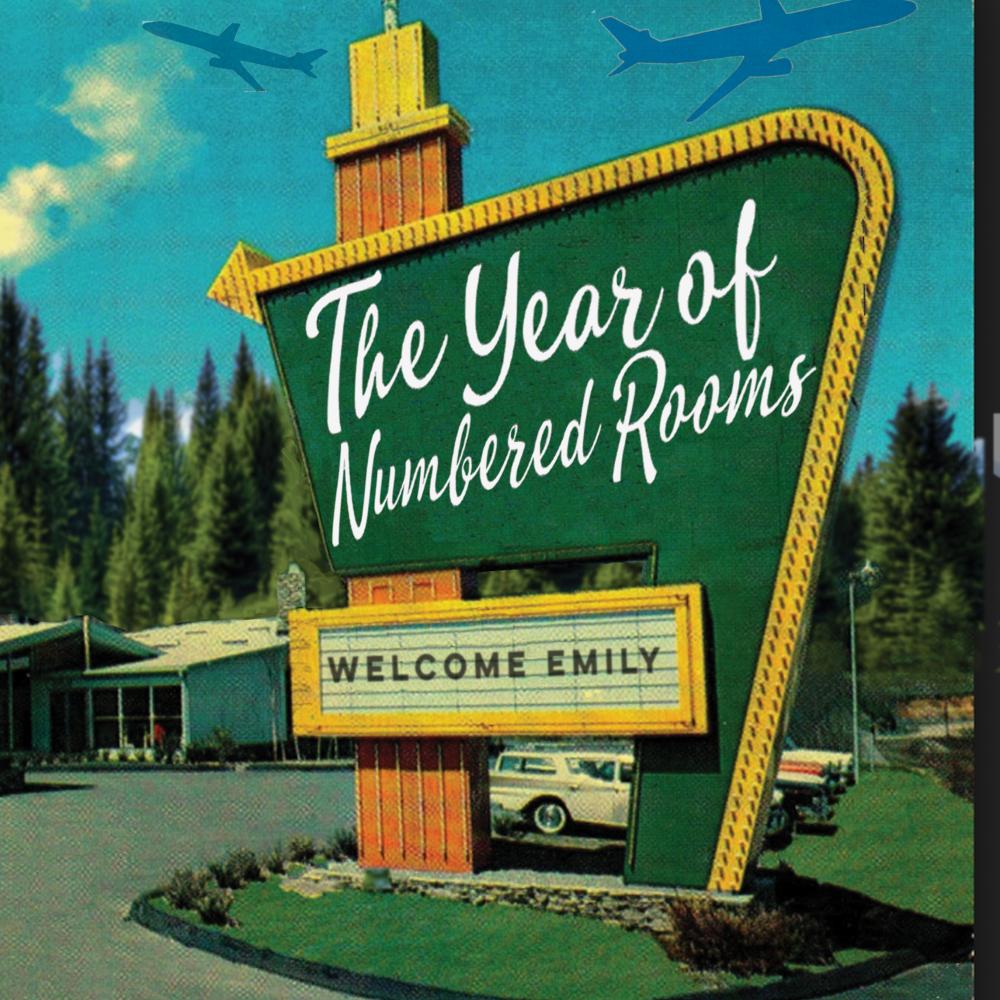

By the time I arrived in Michigan this past fall, I’d been on tour for so long that I had to take a picture of my hotel room door every time I checked into a new place, because otherwise I’d forget my room number. “We have a budget for five cities,” my American publicist had told me at the outset, before the book for which I was touring came out, but then five cities somehow became 17, then 30, and then the tour turned into a sort of self-perpetuating phenomenon that seemed somehow to replicate by itself.

The e-mail from the Michigan Humanities Council arrived in January 2015, somewhere around my fortieth book tour event: The book had been chosen as the 2015–2016 Great Michigan Read selection. It’s a biennial program, in which a series of regional committees pick a book that has some bearing on both Michigan and the humanities. I have no particular connection to the state of Michigan, but the book in question, Station Eleven, involves a traveling Shakespearean theater company in a postapocalyptic Michigan lakeshore region. If I agreed to participate, the Michigan Humanities Council would distribute several thousand copies to schools and libraries and then send me on a series of tours all over the state.

I was declining most event offers by that point, because it was clear by then that what had started as five cities in six or seven days was going to be something closer to 50 cities in 14 months. I am aware at all times of how lucky I was with Station Eleven, having published three previous novels that came and went without a trace, but it is possible to exist in a state of profound gratitude for extraordinary circumstances and simultaneously long to go home. I missed my husband. I was increasingly worn down by life in hotel rooms and airports, and worn down by other people; most of the people I’d met on tour had been wonderful, but a few too many seemed to expect serious responses to questions and statements like, “What’s with all the sentence fragments?” and “Don’t take this personal, but I found your characters a bit over-the-top, by which I mean they weren’t believable” and—my personal favorite—“Obviously, All The Light We Cannot See was better, but yours was good too.” In the brief intervals when I was home between tours, I’d come to dread the inevitable hour when I left for the airport.

Still, I never seriously considered declining the Michigan Humanities Council’s offer. The book sales were, of course, a factor, but the nature of the Great Michigan Read program itself was deeply appealing to me. The goal of the program is to encourage literacy and community, whereas the usual goal of a book tour is to encourage book sales. Also, I’d written a book set partly in Michigan, and that book had changed my life. Perhaps, I thought, committing to four or five brief tours in Michigan was the least I could do.

2.

When the first of the Great Michigan Read tours began, ten months later, I’d done 99 events in seven countries. That fall I sometimes felt as though it might be possible to somehow break through the tour, the way long-distance runners break through a wall of exhaustion to find something approaching transcendence on the other side. My collection of hotel-room door photos had become an accidental travelog. Some were more memorable than others. Where were rooms 323, 810, and 122, for example? I have no idea.

Room 948, on the other hand, was where I discovered I was pregnant. This was in Auckland, New Zealand. I told my husband via FaceTime—he was just sitting down to dinner in New York—and took a pink-and-gold pen from the room to perhaps give to the child later. “This pen’s from the room where I became aware of your existence,” I’ll tell her, unless she’s an unsentimental child who doesn’t appreciate mementos or quality pens, in which case I’ll keep the pen and will wonder if she was possibly switched at birth.

Travel was easier before Room 948 than after, although never as difficult as I feared it would be. The tour shifted from the Antipodes to the Midwest. Room 409 was the best room, in Iowa City. It had a kitchen, I could walk to the event venue, and the hotel was next to a grocery store. Room 411 was the worst of all the rooms, in a Marriott. Where? It doesn’t really matter, because all Marriotts are the same. “Have you stayed with us before?” the woman at the front desk asked, and I honestly wasn’t sure how to answer, because if you’ve stayed in one Marriott, haven’t you stayed in all of them? The room was very beige. The corridors were empty. It was a long dark Marriott of the soul, but what made it a bad room wasn’t that it was a Marriott, it was that there was yet another gun massacre in a different state that day.

I was born in Canada, and lived there until I was 22. I’ve held dual citizenship from birth, because my father’s from California, and I love living in New York City, but the truth is that growing up in a country with strict gun-control legislation can lead to certain difficulties in adapting to life in the United States. I limped through that night’s lecture and then spent a long time alone in the room, thinking of the latest round of bereaved families and overcome by loneliness and wondering if I was making a fatal error in raising a child in this country. In the morning I traveled home for events in New York and New Jersey, and then on to Detroit for the first of the Great Michigan Read events.

That was my one hundredth event for Station Eleven, and the night was invigorating: In the town of Grand Haven I sat onstage in a state of awe and delight while the players of the Pigeon Creek Shakespeare Company performed a medley of scenes from Lear, Hamlet, and Romeo and Juliet. (The traveling company in Station Eleven performs all three plays, although I excised the latter two from the final draft for the sake of narrative velocity.) Pigeon Creek is Michigan’s only full-time touring Shakespeare company. They are dazzlingly good. Every so often, between scenes, I got up and read, and there was such joy in collaborating with other artists, after standing behind so many podiums alone. The other events on that tour were fine, but not as good as the Grand Haven event, because the Grand Haven event had the Shakespearean troupe. If we lived in an alternate universe where authors could have tour riders, I decided on the flight out of Michigan, I would require Shakespearean actors at every stop.

I flew to Chicago, or more precisely to a hotel marooned in an ocean of parking lots on the outskirts of Chicagoland. The lights of big-box stores shone in the distance. The hotel bar was full of independent booksellers. I stayed in Room 627 that night, memorable because it was the first room in some time with a window that opened. By then the pregnancy was extremely obvious. “Congratulations,” one of my favorite Penguin Random House sales reps said, in the hotel lobby. “I don’t know how you found the time.”

That day there were two school shootings, in different states. That night I lay awake in Room 627 while the baby fluttered and kicked. Please be okay, I thought. I know I can’t save you from every danger but just come to us safely, my beloved, my daughter, and we’ll try to protect you in this terrifying country.

3.

From Chicago to Saint Paul, Hartford, Omaha, Des Moines, Boston, Red Deer, Spokane. By Spokane, flight attendants were giving me that “please, for the love of god don’t go into labor in the air” look when I boarded airplanes. Home for a few days, then back to Michigan for the second Great Michigan Read tour. I flew into Pellston Airport, which is one of my favorite airports in the world, because it’s easily the strangest I’ve ever seen. There are taxidermied black bears and a cougar by baggage claim. The stuffed elk are in the waiting area. Down to the beautiful lakeside town of Petoskey, where, for once, my usual request for an onstage interview in lieu of a lecture had been granted. My interviewer asked if there was anything in particular I’d like for him to cover.

“Surprise me,” I said. After over a hundred events for the same book, I longed by then to be surprised, which is why I’d taken to requesting the onstage-interview format. Usually when I tell interviewers to surprise me, the surprise is that they’ve somehow managed to reproduce, nearly verbatim, the same ten questions that I’ve heard in the previous 40 cities. But that afternoon the questions were unusual and piercing, and weeks later, I found myself thinking of them at odd moments: In the first chapter, when the actor dies onstage, you compare the stage to a terminal. In what way is a stage like a terminal? And given the content of the scene and the double meaning of the word ‘terminal,’ in what way is a performance like a death?

In Benzonia a day later, I was eating lunch at a restaurant when a man came in with a handgun in his belt. I stopped breathing for just a second, but I’ve been in the United States for over a decade and immigration requires certain adjustments, so I spent the rest of the lunch watching him in my peripheral vision and trying to concentrate on what my lunch companions were saying. This state has open carry, I reminded myself. He’s not a criminal, he’s just not brave enough to face the world unarmed, and I should try to have some compassion for this. So long as no one startles him, we’ll all get out of here alive.

We survived lunch and carried on to the lovely old building that houses the Benzonia Public Library, where I sat in an armchair and delivered a lecture. Ninety people showed up for the event, which was startling in a community with a 2010 census population of 497. “Perhaps one more question,” I said finally, at the end of the audience Q&A.

A woman at the back raised her hand to ask whether my book is modern or postmodern. I’d actually never thought about it. It occurred to me that if I were a little less tired, I’d be able to remember the technical definition of what constitutes a postmodern novel and could probably dance my way to an adequate response, but in that moment both the definition and the jargon eluded me. “I don’t know,” I said.

“Even though you don’t know much about literature and couldn’t say whether your book’s modern or postmodern, I think your book could still be taught in colleges,” she assured me later, in the signing line. Even though you don’t know much about literature. I refrained from throwing a book at her head and left as quickly as possible for Scottville.

The day was bright, until somewhere outside Elberta, a heavy fog descended over the road. Within the cloud, there was an apple orchard, gray and dripping, trees skeletal in the white, the orchard replaced by the ghostly silhouettes of marsh grass as the road passed near a lake. I was thinking of the beauty of this state, of the tremendous good fortune of getting to see so much of it on these tours. I was thinking of the man with the gun in the diner, realizing that I’d been witness to a performance: What he wanted, when he left the house that morning with a deadly weapon in his belt, was to play the part of an invincible man. (In what way is a performance like a death?) I was thinking of the way the tour had begun to mirror the book; we traveled endlessly, my fictional characters and I, afraid of violence and sustained by our art, exhausted and exhilarated in equal measure, and the costs were not insignificant but we’d chosen this life.

4.

I deliver my lecture in Scottville that night, and the last Great Michigan Read tour of 2015 is over. I’ll come back to Michigan a few times in the spring, but for now there’s just one more festival, this time in the south, and then finally, after 126 events for Station Eleven, I’ll go home. I’m having difficulty believing that this is actually true, because the thought of going home and staying there, going home without plans to return to the airport in 48 hours, is almost inconceivable at this point. I arrive at my hotel at 11 p.m. that night, and rise at four to fly to South Carolina.

More and more lately, and especially in the air, I’ve found myself silently narrating the tour to my daughter. The year before you were born, my love, I traveled constantly. It was sometimes magnificent and sometimes numbing. I knew the best places to eat in a dozen airports. (The plane descends into the Carolinas, still green in November.) I was very tired, but there were moments of grace.

It was a year of loneliness and long flights and spectacular good fortune, a year of numbered rooms and standing behind podiums. “Culture,” I told the audience, “is an antidote to chaos,” although that year the chaos seemed exceptionally strong. It was a year of mass shootings, of blinking back tears in airport lounges beneath televisions tuned to CNN, of reading about new massacres in hotel rooms at night. The violence that year was stunning and constant and it was easy to conclude that it would never end.

But every day of the tour, in seven countries, I met people who cared about life, about civilization, about books, and by the end of the tour this seemed to me to be a reasonable antidote to despair. I thought very often about the world you’d be born into, about what it means to hold on to one’s humanity in the face of horror. In my life, the humanities have been the antidote to mere survival. In the book for which I traveled, the line Survival is insufficient is tattooed on someone’s skin.