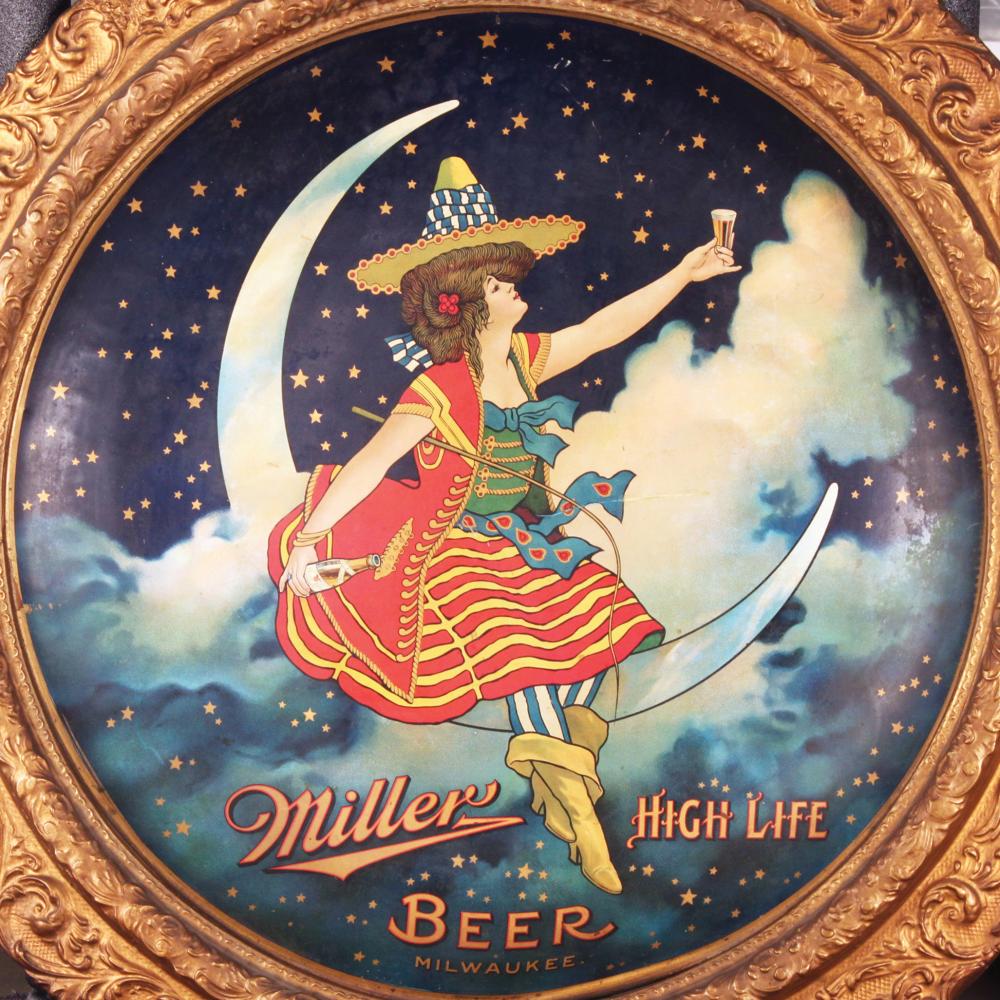

On a dark night in rural Wisconsin, Miller marketing guru A. C. Paul gets lost in the Northwoods. No doubt having sampled his own wares, he staggers through the wilderness, trying in vain to find his way out. Then a beautiful woman appears in the moon and steers him back to civilization. Or so the legend goes. In 1903, the so-called “girl in the moon” became the face of Miller High Life beer. Albeit with a significant makeover, she continues to grace bottle necks to this day.

While some say the mysterious girl in the moon was modeled after a daughter of the Miller family, Milwaukee nurse Linda Hoffman claims her own family ties: She is on a mission to prove that her great uncle, Thomas Wallace Holmes, was the original artist and that he used her grandmother, Ruth Strauss, as his model. Whatever her origins, the girl in the moon helped launch a marketing phenomenon that swept the nation. Mythical creatures like angels, elves, and goats in tuxedos announced the beers of Wisconsin alongside cityscapes, brawny men, and, of course, sultry women. The breweries’ campaigns brought two big changes: They laid the foundation for modern marketing, and they put Wisconsin on the map.

The turn of the twentieth century was a sweet spot for beer advertising. For one, industrial improvements had transformed local breweries from neighborhood watering holes into major operations—places like Milwaukee were producing more beer than even their most devoted constituents could drink, and now they had the railways to ship it. Meanwhile, the technology of lithography had advanced to the point where companies could make bright, new color prints in batches large enough to circulate nationwide. In the years leading up to the start of Prohibition in 1920, when the Eighteenth Amendment outlawed the sale of alcohol, these developments helped Wisconsin brewers build a lasting reputation.

Milwaukee breweries “had a lot of hurdles to get over when they started trying to get their product and their name out there,” says Erika Petterson, curator of “Art on Tap: Early Wisconsin Brewery Advertising,” an exhibition at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend supported by the Wisconsin Humanities Council. “On the East Coast and in New York people laughed at them: ‘who are you? You’re this little backwater . . . on the edge of nowhere.’” The first step toward a higher profile wasn’t to promote the product, or even the consumer, Petterson says—it was to market the place itself with bird’s-eye views of a glittering industrial metropolis. “We were not these teeny-tiny towns anymore—we were progress.”

Once breweries like Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz, Potosi, and Miller gained footholds in new markets, they became some of the first companies to solidify the concept of consumer identity, according to the exhibition. John Gund Brewing Co., now defunct but thriving in the days before Prohibition, used the slogan “House Committee on Refreshments” for separate ads showing blue-collar workers hauling a keg into the park and men in suits drinking out of fine glassware. This was the era when Miller coined the epithet “Champagne of Beers” for their High Life—back then, the “Champagne of Bottle Beers.”

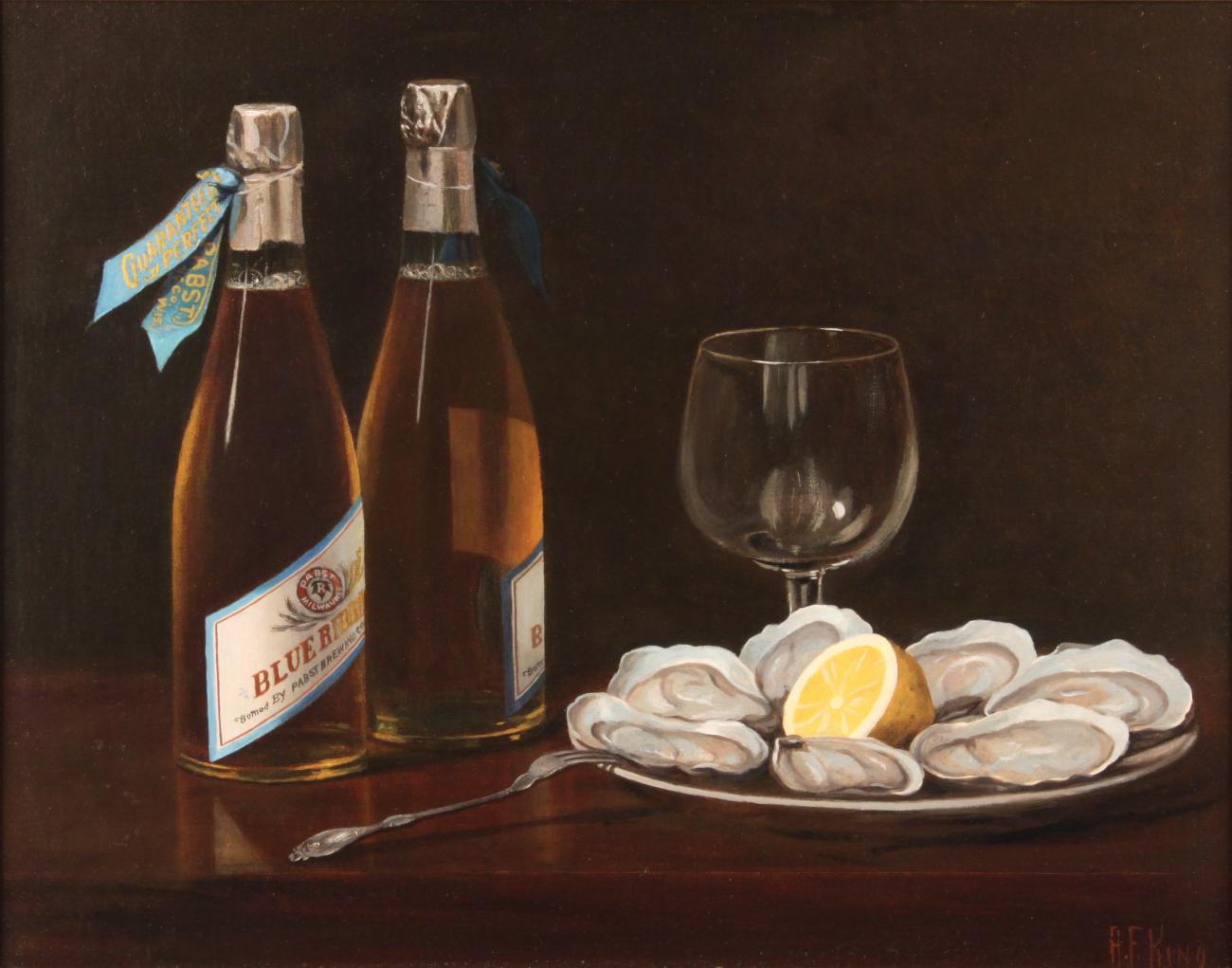

Pabst, too, came up with a novel gimmick for their Best Select brew: In 1882, they started tying a blue ribbon around the neck of each bottle. The drink of choice for modern-day hipsters, recognizable simply by the initials PBR, was originally marketed as a high-end beverage. An oil painting in the exhibition shows two of these bottles, not only ribbon-bedecked but also topped with gold foil, alongside a stemmed glass and a plate of oysters on the half shell. The still life, commissioned by Pabst circa 1903, was made into a lithograph and became one of the most famous ads of the early twentieth century.

Wisconsin breweries courted clientele of all sorts. Just as they do today, they cast a wide net with humor, celebrity, and sex appeal—“pretty ladies have always been advertising beer,” says Petterson. Most out of place to the modern eye, a print of a woman spoon-feeding Pabst to her baby introduces a series of ads for “tonics,” the medicinal beers that helped keep brewers in business through thirteen years of Prohibition. “A Boon to Old and Young,” reads one of the ads, touting its product as a cure-all for exhaustion, mental health, old age, and breastfeeding. The last of these, at least, has stuck, though the many mothers who subscribe to it today tend to use brewer’s yeast instead of the final product.

In many households, brewery ads from mailings and magazines took the place of more expensive visual art. “One of the advertising strategies was, the more beautiful the object, the longer they’ll keep it up on their wall,” says Petterson. “It may be a little girl and her dog, and she’s adorable and the colors are pretty, but we’ll put ‘Potosi’ on the top, and they’ll see that every time they look at it.” The new inks and printing styles used for marketing led to shifts in color theory that extended to more traditional forms of visual art.

“It’s not your standard art museum fare,” Petterson says, describing the collection of posters, calendars, tin trays, mugs, and even a towering mint-condition billboard of a racing yacht that make up the exhibition. The items come from a handful of local historical societies, the Potosi National Brewery Museum, the Pabst Mansion in Milwaukee, and four die-hard collectors of “breweriana.”

After the Twenty-first Amendment lifted Prohibition in 1933, beer advertising was never quite the same. This was, in part, because some state legislatures lagged behind the Constitution, and the watershed that could have been was instead more of a trickle. The Federal Alcohol Administration began to limit advertising methods in 1935, and when television took off in the 1940s, breweries struggled to adapt to the new medium.

More to the point, Petterson says, the pre-Prohibition cultural moment had passed. “There’s a rarity to it and a uniqueness. Once you get into some of that later stuff, that mass-produced, really commercial stuff . . . it’s not quite the same for me.”

You would be hard-pressed to find a Milwaukeean with more than a couple degrees of separation from one of the major breweries. Everyone’s grandfather, it seems, did a stint sorting bottles for Miller, or fermented lager for Schlitz. These ties have helped draw an eclectic crowd. “Beer is so relatable in Wisconsin,” Petterson says, and the topic has attracted “people who haven’t been to an art museum, or haven’t been to this museum.” The three beer tastings hosted at the exhibition haven’t hurt, either.