Three hundred years is a long time to suffer a bad reputation. In fact, the sheer longevity of the idea that New Orleans is somehow a bad girl among her sister cities makes it all but impossible to successfully challenge the idea. Take, for example, a story that appeared in Vanity Fair magazine in November 1934, titled “New Orleans is a Wicked City.” The author, Marquis W. Childs, promised his readers “an excursion into the glamorous past, and an examination of the sordid present.” For Childs, the most damning aspect of the city’s toleration for wickedness was embodied in a still-thriving prostitution district, to which he provided very good directions, perhaps inadvertently, to readers who should wish to find it for themselves.

The particulars of the city’s allegedly sordid present had been brought to light two months earlier, when Senator Huey P. Long roared into town, surrounded by armed bodyguards, accompanied by hundreds of the state’s National Guard troops, and animated by politically motivated outrage about allegedly widespread vice in New Orleans. Long ensconced himself in the Canal Bank Building, where he summoned and questioned numerous witnesses about the city’s toleration of, if not outright support for, many kinds of vice, especially prostitution and gambling. Though Long refused to admit journalists, or the lawyers of those he questioned, into his hearings, he did have the proceedings broadcast on radio stations under his sway. In Kingfish: The Reign of Huey P. Long, Richard White describes how Long began each radio broadcast by promising to clean up gambling, to end graft paid to city officials, and to “stamp out prostitution,” noting that “the red light district has expanded to the point of national disgrace.”

In the end, everyone, including Childs, conceded that the scandal-mongering hearings were a sideshow, nothing more than an attempt on Huey’s part to swing voters toward his purportedly more upright slate of candidates just days before an election. “What was really remarkable,” Childs wrote, “was that anyone should, at this late date, even professedly for the purposes of making political capital, become aroused over the wickedness of the city at the end of the river. For New Orleans has been wicked for a long time.”

Childs was certainly not the first journalist to offer a breathless exposé of the city’s robust underworld. Fourteen years earlier, journalist Lyle Saxon authored a five-part series for the Times-Picayune titled “New Orleans Nights: Little Adventures in Devilment.” The series began its run only days after Prohibition had taken effect nationwide and, despite this new inconvenience, the author promised to “set forth the many and devious ways one may see New Orleans in its new, officially sober iteration.” Throughout the series a fictionalized couple goes out on the town night after night in pursuit of pleasure and excitement. On their first foray into devilment, they easily locate plentiful alcohol, gambling, and the option of sex for sale. And, as Childs had done, Saxon helpfully provided interested readers a map of how to find the same locations for themselves. Saxon’s “New Orleans Nights” series anticipated the practice of using vivid descriptions of the city’s establishments to not only titillate but also inform and perhaps convince readers that reform was long overdue. And, as had been the case in 1934, these kinds of newspaper stories—or anti-vice campaigns—often arose in close proximity to elections in which one candidate positioned himself as a reformer and his opponent as a protector of the city’s politically powerful vice interests.

The city’s reputation as a laissez-faire home for vice crystallized, at least in the twentieth century, in the segregated district that came to be known as Storyville. New Orleans had been attempting to corral prostitution into more manageable spaces since at least 1857. But in 1897, a newly optimistic reform administration, in power for all of one term, passed the ordinances that created the city’s last but most notorious vice district. Brothel prostitution was still quite common in the nation’s cities at the beginning of the twentieth century; what set New Orleans apart was the frank and direct way city officials chose to deal with it. Instead of ignoring brothels, protecting brothels through graft, or allowing prostitution to exist in informally recognized districts, New Orleans officials acknowledged their belief that sins of the flesh were inevitable. In response, they looked Satan in the eye, cut a deal, and gave him his own address.

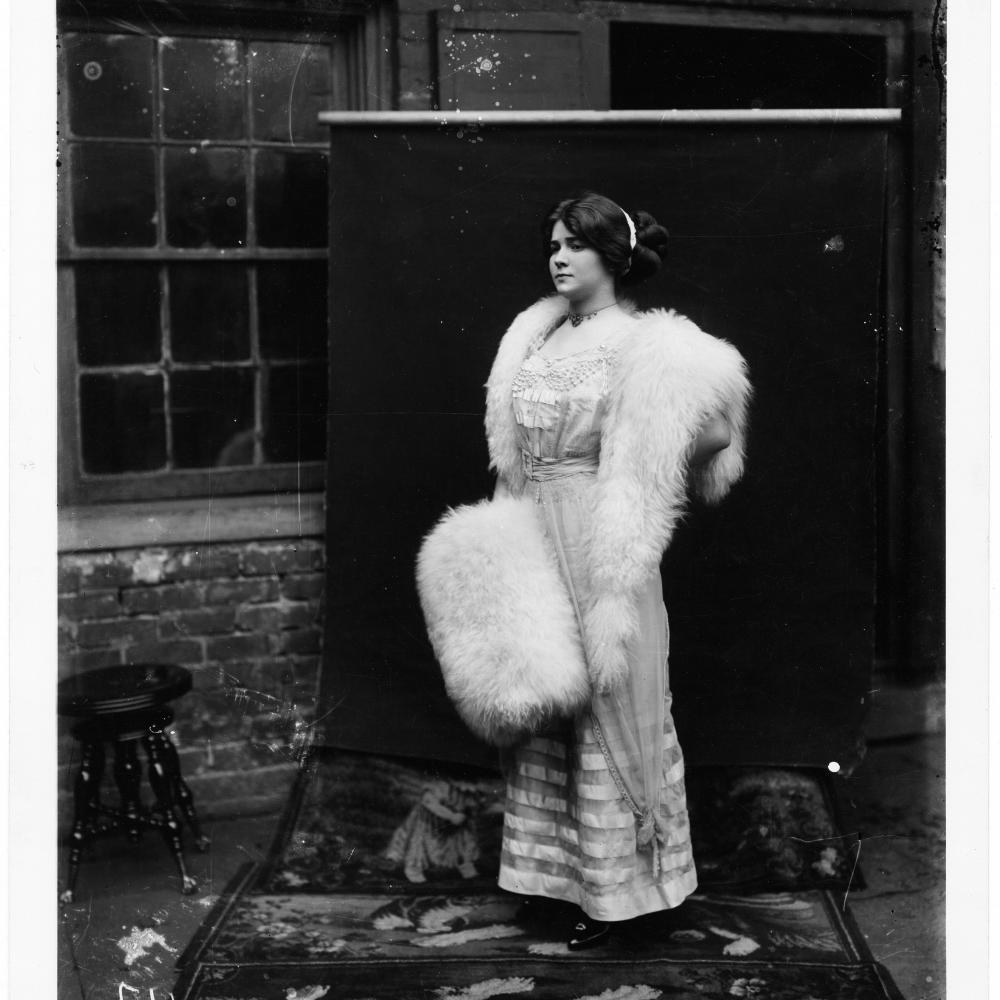

That “address” encompassed all or part of nineteen city squares located just behind the French Quarter, home to more than 360 structures. Over the next decade that number actually increased as prosperous bar and brothel owners built flashy new establishments, especially on Basin Street, the district’s gaudy main thoroughfare. Brothels were the main attraction, but barrooms, gambling dens, and all manner of entertainment outlets rose and fell in the seasonal economy that developed inside Storyville. Many out-of-town visitors came to the city during the winter racing season, which began in November and ended in early spring, after Mardi Gras. Some Storyville prostitutes simply stood in the doorway of their modest single-room cribs, calling to potential patrons and passersby. Other establishments sought to draw customers inside with such gimmicks as floor-to-ceiling photos of nude women, prizefighting portraits and memorabilia, or draft beer to go, a nickel a bucket. Other saloons sought to impress customers with ornate finishes and decorative details. In this category none exceeded Tom Anderson’s Basin Street saloon, which opened in 1901. Besides being a well-known figure in the district, Anderson was also politically influential. Journalists sometimes referred to him as The Mayor of Storyville. In point of fact, he served as an elected representative to the Louisiana state legislature, where he and like-minded New Orleans officials defended the district to its bitter end.

That end came in 1917, not because local reformers were successful or city officials agreed with the decision, but because federal officials ordered the closure of brothels and vice districts within five- to ten-mile zones around the training camps being set up to prepare soldiers for U.S. entry into World War I. Despite vigorous efforts to defend segregated vice, New Orleans Mayor Martin Behrman received orders from Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels to close the district. Finally defeated, Behrman introduced an ordinance, and Storyville was officially closed on November 12, 1917.